At the eleventh annual meeting of the Swiss Society for Drug Safety in Psychiatry (SGAMSP), held at the Schlössli Private Clinic, Oetwil am See, which is steeped in tradition, three topics were taken up that are frequently discussed nowadays in connection with the human brain: Mild Cognitive Impairment, Neuro-Enhancement and Burnout. The question was to what extent the use of psychotropic drugs is useful or risky.

Prof. Dr. med. Dr. rer. nat. Martin E. Keck, organizer of the conference and medical director of the Clienia Privatklinik Schlössli, drew attention to the fact that sales of antidepressants are increasing and that the number of sick days due to psychological stress at work has also risen by 80% in the last 15 years. This raises the question of how great the benefits and risks of the psychotropic drugs used are and whether they represent a useful therapy in life crises.

The great oblivion

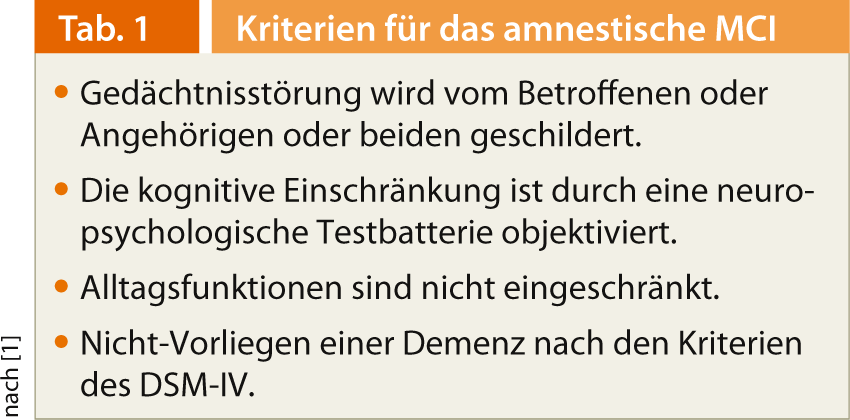

First, PD Dr. med. Thomas Zetzsche, head of geriatric psychiatry at the Schlössli Private Clinic, dealt with “Mild Cognitive Impairment” (MCI). The term was introduced by Ronald C. Petersen and colleagues in the late 1990s (Table 1). They wanted to fill the gap between normal aging and dementia. “The concept allowed characterization of a high-risk group for developing dementia, and later it was extended to non-amnestic forms of MCI,” Dr. Zetzsche said. “So now there is amnestic MCI (aMCI), which often converts to AD, especially when biological markers of AD are detectable (e.g., hippocampal atrophy and amyloid detection on cerebral imaging), and non-amnestic MCI (non-aMCI), which may show a favorable course or convert to other forms of dementia.” According to ICD-10, MCI primarily manifests difficulties in one or more of the following areas:

- Memory (especially remembering and learning new things)

- Concentration and attention

- Thinking (e.g., slowed problem solving, difficulty with abstracta).

- Language (word-finding or comprehension problems).

- visuo-spatial functions.

“To identify MCI, it is therefore always important to find the middle ground between cognitive changes that are no longer within the normal range of age physiology, but also do not reach the extent of dementia. In particular, the ability to cope with everyday life should be preserved,” Dr. Zetzsche emphasized. The diagnosis is analogous to that of dementia. First, a syndrome diagnosis takes place: Is there a deficit corresponding to the aforementioned classification systems that differs from the normal aging process? Tests (e.g. “Delayed Recall”), questionnaires and standardized interviews with the affected person and relatives are used for this purpose. After that, the severity and etiology must be added to the differential diagnosis. Is there a treatable cause of MCI, such as a vitamin deficiency or infection?

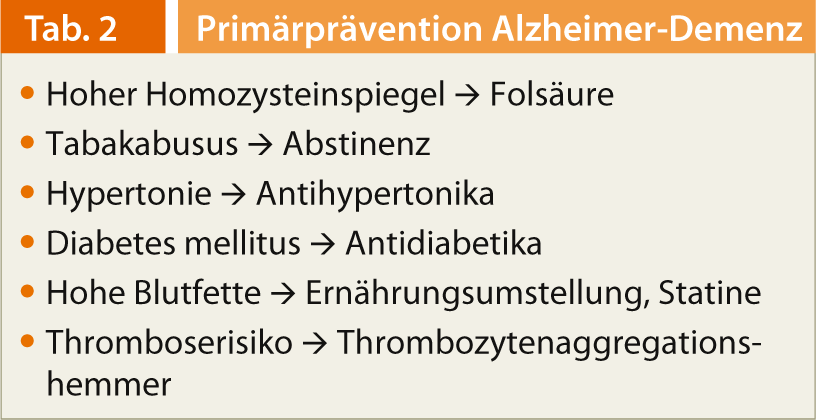

AMCI that converts to AD is treated symptomatically using cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine. There are currently no reliable findings on the specific therapeutic approach still in the stage of aMCI. “Neither acetylcholinesterase inhibitors nor memantine show sufficient evidence of efficacy in aMCI according to current studies. Therefore, it is central to advance the primary prevention of AD, i.e. to identify risks at an early stage and to avoid or treat them,” says Dr. Zetzsche (Tab. 2). “The hope for the future is to develop so-called disease-modifying therapies to halt or slow neurodegeneration.”

The optimized human being

The second speaker, Prof. Dr. med. Michael Soyka, Meiringen, dealt with neuro-enhancement: “As the name suggests, it is about increasing the mental performance and psychological well-being of healthy individuals, ultimately about the dream of an optimized human being. This is why it is also referred to as neuro-doping. If current reports are to be believed, the use of psychostimulants in particular, such as Ritalin® and Modafinil, is commonplace at U.S. universities and increasingly so in Europe.” Drugs used to treat degenerative diseases in particular are also suitable for enhancing the performance of healthy individuals. Specifically, stimulants, amphetamines, modafinil, antidementives (e.g., donepezil), and antidepressants (SSRIs: e.g., fluoxetine) are used in neuro-enhancement. In addition, the following measures and behaviors, some of which are visions of the future, can be included in this area:

- Preimplantation genetic diagnosis enables selection of particularly high-performing embryos.

- Brain-computer interfaces and cortical implants augment and alter psychic and mental functions.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation enhances thinking performance.

“A distinction must be made between whether the aim is to improve cognitive abilities or mental well-being. In the former case, methylphenidate, modafinil, piracetam or memantine, among others, are used; in the latter case, fluoxetine or β-receptor blockers such as metoprolol,” says Prof. Soyka. “Those who now think this phenomenon occurs only in the U.S. are proven wrong by a 2012 Swiss study [2]: 80.2% of Swiss psychiatrists and primary care physicians report receiving requests for “neuroenhancing products” once or twice a year, with 9.6% following patients’ requests.”

Burnout risk state

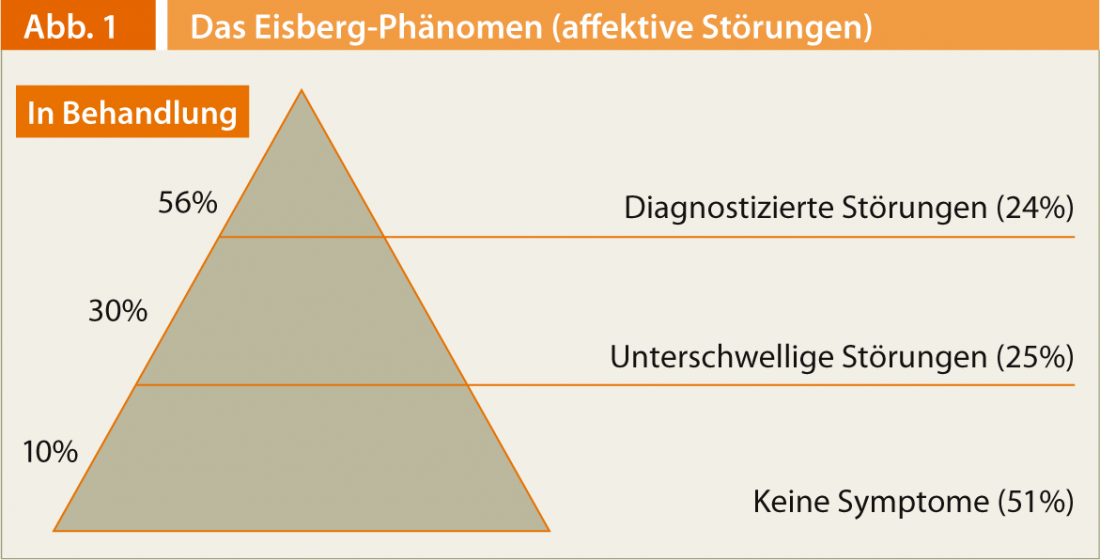

In the second part of the lecture series, Prof. Gregor Hasler, MD, from the University Clinic for Psychiatry in Bern, spoke about burnout: “It is not an actual disease, but a state of risk.” First, he referred to the so-called iceberg phenomenon, which shows that the majority of people with affective disorders have no diagnosable symptoms and therefore only a small proportion of them, about 10%, are undergoing treatment (Fig. 1). However, subclinical symptoms, such as those of burnout, are not harmless in the course: they lead to suicide attempts and incapacity for work with about the same frequency as mild or moderate depressive syndromes. The risk of transition to severe mental disorders and hospitalization rates are comparable to the corresponding risk for moderate-grade syndromes. “When we talk about risk factors for depression, it becomes apparent that psychosocial stress is very important as a risk factor, especially at the onset of a depressive development. Many depressions with a chronic course begin reactively and become more and more endogenous in the course, i.e., the risk for spontaneous episodes increases continuously,” says Prof. Hasler. “That’s why burnout needs to be taken seriously and addressed correctly. With progression into clinical depression and progressive disease duration, the chance of sustained remission decreases dramatically [3]. Failure to achieve remission in turn leads to the following problems:

- Increased risk of relapse

- Increased chronic course

- Shorter intervals between episodes

- Continued inability to work.”

Because each new depressive episode increases the risk for more, treatment for unipolar depression should be given for three to six months for the first episode, as early as two years for the second, and five years to life for the third episode, or other increased risk. These recommendations are based on the very favorable benefit-risk ratio of antidepressants. For example, Kornstein and colleagues showed in 2006 that continuous treatment with the antidepressant escitalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), was well tolerated and effective in preventing relapse [4].

Source: “11th Annual Meeting of the Swiss Society for Drug Safety in Psychiatry (SGAMSP)”, September 26, 2013, Oetwil am See.

Literature:

- Petersen RC: Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004 Sep; 256(3): 183-94.

- Ott R, et al: Neuroenhancement – perspectives of Swiss psychiatrists and general practitioners. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012 Nov 27; 142:w13707. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13707.

- Keller MB, et al: Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression. A 5-year prospective follow-up of 431 subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992 Oct; 49(10): 809-16.

- Kornstein SG, et al: Escitalopram Maintenance Treatment for Prevention of Recurrent Depression: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67: 1767-1775.