Pneumatoceles occur very rarely in clinical practice. Spontaneous pneumatoceles as a complication of COVID-19 infection have rarely been documented. Even fewer cases report spontaneous pneumothorax as a complication of pneumatocele. As a rule, conservative treatment is indicated in stable patients, but in severe courses there is usually no way around surgical intervention.

Pneumatoceles, also called pseudocysts, are thin-walled, air-filled cysts that form in the lung interstitium. They result from an inflammatory reaction in the bronchus that leads to the formation of an endobronchial ball valve that prevents air from leaving the bronchus. This results in distal dilatation of the bronchi and alveoli and air trapping, write Utku Ekin, M.D., Department of Internal Medicine, St. Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson, New Jersey, and colleagues [1]. In the course, the pneumatocele may be further extended by another pneumatocele or by inflammatory exudates; in more than half of the cases, hemoptysis occurs, followed by chest pain and cough. Most cases of pneumatoceles are asymptomatic and often occur after damage to the lung parenchyma, such as after bacterial or viral pneumonia.

Although pneumatoceles are primarily infectious in origin, they may also result from other pathophysiologic mechanisms, such as trauma or surgical procedures. In the emergency department, physicians were dealing with a patient who developed a large pneumatocele and further a severe complication of spontaneous pneumothorax after infection with SARS-CoV-2.

CT shows more than X-ray

The 43-year-old woman presented with complaints of shortness of breath and cough, and her medical history indicated hypertension. The SARS-CoV-2 test was positive. A chest radiograph showed a consolidated infiltrative process in the right middle lobe; in stable condition, the patient was discharged home. However, 7 days later, she was again in the emergency room; shortness of breath and cough had increased, and the woman also developed a fever. She was admitted for treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia. The new radiograph showed a large new bulge in the right upper lobe that had not been seen previously (Fig. 1) . The physicians followed up with a computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest to rule out pulmonary embolism in the presence of persistent hypoxia and tachycardia. They discovered a large right-sided pneumatocele occupying a significant portion (>50%) of the right hemithorax (Fig. 2) . After completion of COVID-19 treatment, the patient was discharged. Due to the size of the pneumatocele and the risk of further complications, outpatient follow-up with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) was considered.

It didn’t get that far: two days before the scheduled procedure, the patient presented again to the emergency department with severe right-sided chest pain and shortness of breath. Radiography showed a new right-sided pneumothorax, and noncontrast CT also showed a large pneumatocele. A thoracostomy was then performed on the right side. The patient experienced a slight re-expansion of the right lung and a slight decrease in the size of the pneumothorax.

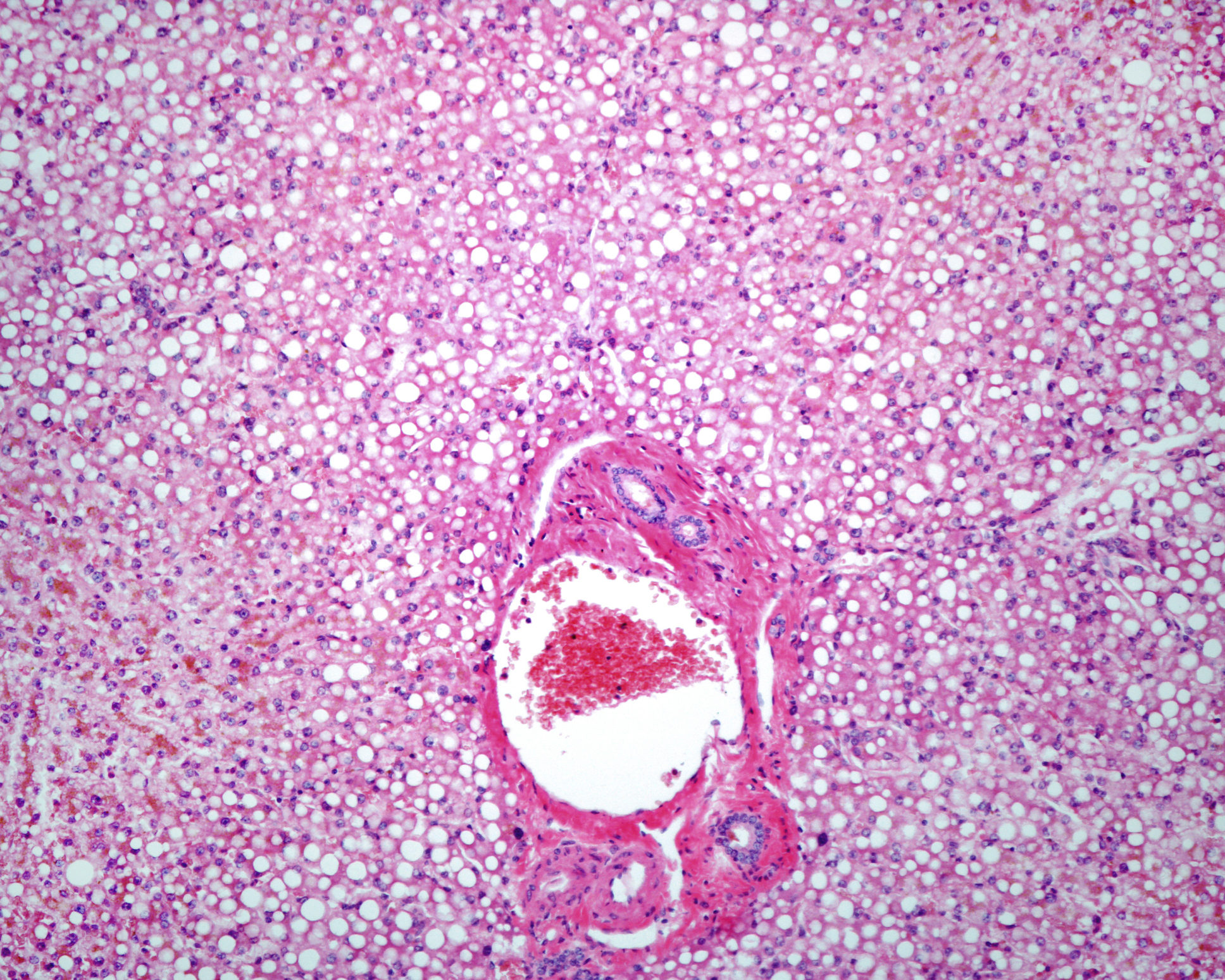

Three days after surgery, a small air leak occurred at the chest drain, and subsequent radiographs showed the size of the pneumothorax to be unchanged, prompting the surgeons to perform VATS. VATS revealed a large amount of intrapleural adhesions and a large pneumatocele in the right upper lobe. The procedure included resection of the pneumatocele, wedge resection of the right upper lobe, intrathoracic lysis of the adhesions, and placement of two chest drains. Histopathologic analysis revealed changes suggestive of acute chronic inflammation, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, and acute fibrinous pleurisy. Two days later, chest X-ray showed improvement of the pneumothorax. Four days after the procedure, the chest tubes were removed, and a small residual pneumothorax remained stable. The patient was discharged home in stable condition.

Early VATS may be the better solution

CT imaging is the best method for detecting pneumatoceles, regardless of cause, the authors write. Most of these cysts resolve spontaneously and do not require surgical intervention. Conservative treatment is therefore fundamentally recommended, especially if the patient is hemodynamically stable. Healing can take several weeks to months. However, severe cases leading to pneumothorax require immediate intervention.

In certain cases, such as a prolonged air leak, hemothorax, or large pneumothorax, or the pneumatocele is pressing on adjacent organs, VATS may be indicated. Although there are no clear guidelines for the surgical approach to pneumatoceles, previous studies have shown the benefits of early surgical intervention, according to Dr. Ekin et al. In stable patients, conservative treatment is advised, but in complicated pneumatoceles occupying more than 50% of the hemithorax, an earlier surgical treatment approach may prove more beneficial. In the reported case, there were several reasons for physicians to initially offer outpatient follow-up with surgical treatment:

- the size of the pneumatocele, which increased the risk of complications,

- the risk of the pneumatocele rupturing and causing a tension pneumothorax,

- the risk of enlargement of the pneumatocele, which can compress nearby structures and cause cardiovascular problems.

The final decision to proceed with surgery should be made after an appropriate risk assessment of the potential complications of pneumatocele and an informed discussion between the patient and the treating physician.

Literature:

- Ekin U, Millet C, Chaudhry S, et al: Successful Management of Spontaneous Pneumatocele and Pneumothorax Formation After COVID-19 Infection. AIM Clinical Cases 2023; 2: e220357; doi: 10.7326/aimcc.2022.0357.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2023; 5(3): 26-27.