The Cardiovascular Day at the Marriott Hotel in Zurich provided a broad overview of the three most important organs in the circulatory system: heart, kidney and brain. In addition to cardiorenal syndrome and chest pain, the main topics included dyspnea, which is often caused by heart failure.

According to Dr. med. Thomas Weinreich, Nephrology Center Villingen-Schwenningen, patients with cardiorenal syndrome “fall between the chair and the bench”: Neither cardiologists nor nephrologists have handy therapy tools and the fundamental question of categorizing this condition arises. However, the heart and kidney are crucially connected: Chronic or acute heart failure (HI) is an important cause of acute or chronic renal failure. Chronic kidney disease (CKD), in turn, is an independent cardiovascular risk factor [1] – “even in the case of not very advanced renal insufficiency with a GFR below 60 ml/min [2],” the speaker explained. Cardiorenal syndrome can be classified clinically into mild (HI + GFR 30-59 ml/min), moderate (HI + GFR 15-29 ml/min), and severe (HI + GFR <15 ml/min or dialysis). In addition, a classification according to time course (acute/chronic) and depending on the underlying disease is useful: For example, if acute renal failure is the underlying disease and heart failure is the secondary disease, one speaks of type III, the “acute renocardial syndrome”.

It goes without saying that the therapy of this difficult disease complex requires close interdisciplinary cooperation. “It’s time to motivate cardiologists to think more renal and nephrologists to think more cardiac” is wisdom that seems indicated in the cardiorenal syndrome. “Because whatever we do pharmacologically, we always run the risk of harming the patient, because renal failure and heart failure sometimes involve exactly opposite pathological processes,” Dr. Weinreich said. It therefore makes perfect sense to think about a department for cardiorenal therapies. In principle, the treatment includes volume decompression on the one hand. Diuretics (both loop and thiazide diuretics for sequential tubule blockade) are used. The goal is a negative sodium and water balance. On the other hand, cardiac function should be improved and potentially nephrotoxic substances such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers or NSAIDs should be suspended. Last, ultrafiltration (peritoneal dialysis, extracorporeal procedures) may be an option.

The patient with thoracic pain: which work-up is useful?

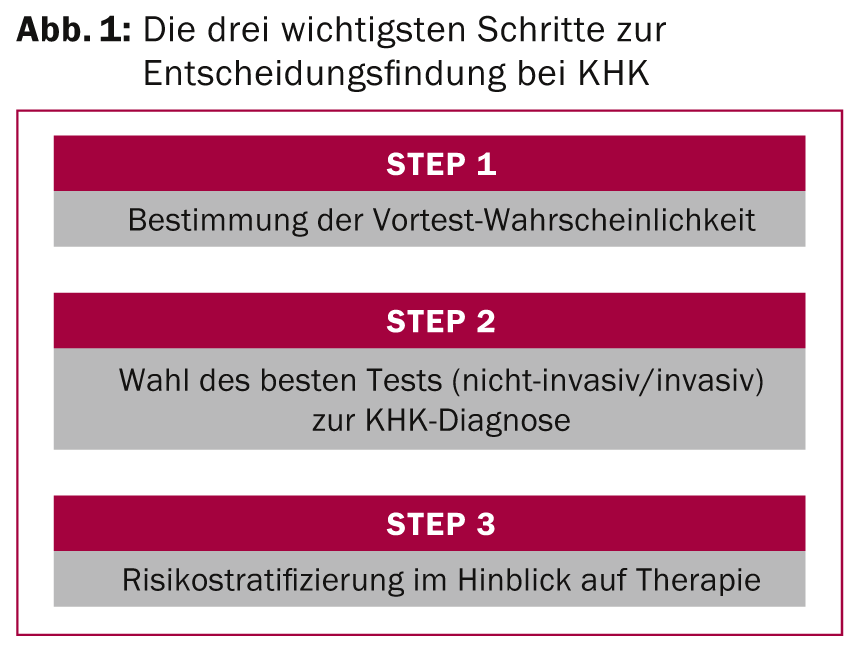

“3% of all GP consultations in Switzerland are due to thoracic pain” said PD Oliver Gämperli, MD, Cardiology, UniversitySpital Zurich. “In principle, this number doesn’t seem that large, but if you factor in the follow-up costs, since one in five patients is referred for additional evaluations, the economic burden is remarkable.” After musculoskeletal causes, coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common cause of chest pain. At the same time, CHD is still the most common cause of death in Europe after cancer, even though CHD mortality has decreased significantly in recent decades (presumably due to better preventive and therapeutic measures). Obviously, then, appropriate diagnosis of thoracic pain is a key switch point in the health care system. Dr. Gämperli therefore listed the three most important steps for decision making in CHD (according to recommendations of the European ESC guidelines for the workup and treatment of CHD [3], fig. 1) .

Pretest probability is sometimes calculated from age, sex, and symptoms (revised Diamond/Forrester criteria). It plays a big role in pretest CHD diagnosis: “According to Bayes’ theorem, a test has the best discriminative ability when the pretest probability is intermediate,” the speaker explained. Regarding the choice of diagnostic test, the following should be said: the cardiac history is still seminal in CHD work-up. The distinction between typical, atypical, and nonanginal symptoms is a widely accepted first approximation of the patient’s clinical picture, but unfortunately does not allow a reliable statement about the presence of CHD in many cases, as recent studies have shown [4]. Accordingly, which further diagnostic procedures are useful? Bicycle ergometry, with a pretest probability of 15-65%, is still a useful test because it is easy to perform and widely available. However, with a higher probability (65%), the significance is imprecise, so that the guidelines recommend additional imaging techniques in this case. These play an increasingly important role in CHD diagnosis and additionally provide key prognostic information. “In this context, the diagnostic accuracy of the different imaging modalities (SPECT, CMR, PET) is roughly comparable. Much more important for the choice of the best procedure is the suitability of the patient (heart rate, metal implants, sound windows, coronary calcifications, etc.),” says Dr. Gämperli.

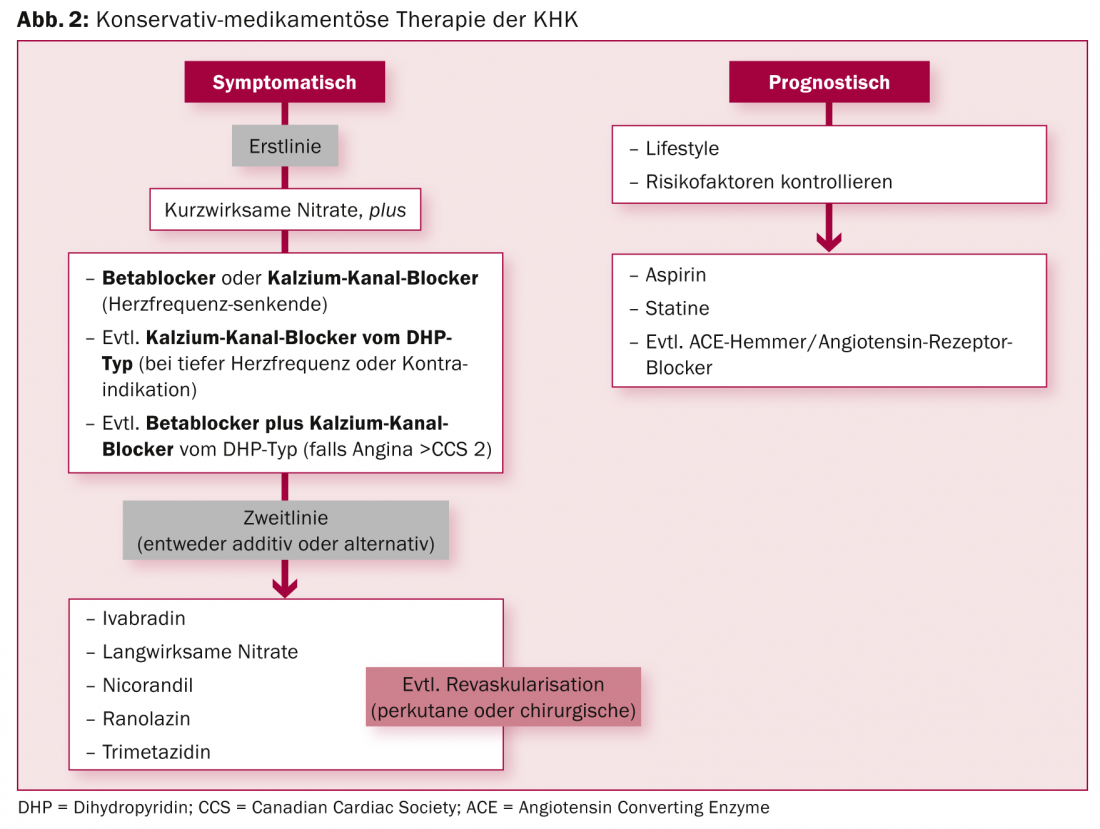

Stable CHD is basically a benign disease with a good prognosis. Most patients can be treated primarily with medication. “However, you have to identify the patients at risk, so stratification in terms of therapy is very important,” the expert elaborated. Figure 2 summarizes the conservative-medicinal therapy options. If revascularization is nevertheless necessary, the modern percutaneous procedure with coated stents (“drug eluting stents”, DES) has proven to be equal to the surgical option in many areas.

Dyspnea – cardiological and pneumological perspectives.

According to Andreas Flammer, MD, Cardiology, University Hospital Zurich, dyspnea is the most important symptom of HI, regardless of whether ejection fraction is preserved or reduced. In acute HI, dyspnea represents a medical emergency with high mortality that deserves appropriate attention (similar to an infarction). “Unfortunately, unlike acute myocardial infarction, interventions in acute HI show little benefit – yet action is needed,” Dr. Flammer said, explaining the dilemma. If blood pressure is normal, diuretics and vasodilators are the mainstays (both improve dyspnea). Serelaxin has also been shown to reduce dyspnea. Furthermore, in the RELAX-AHF trial, all-cause mortality – one of the secondary endpoints – was significantly reduced compared with placebo [5].

In the context of symptomatic chronic HI, Dr. Flammer referred to the drug milestones that were sometimes presented at the 2014 ESC Congress, most notably, of course, PARADIGM-HF [6]. A study by Ruschitzka et al. [7] also showed in 2013 that cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) does not benefit, but rather harms, narrow QRS complexes.

Dyspnea in HI with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) represents an important and underappreciated differential diagnosis. Diuretic therapy is the cornerstone of treatment there as well. However, the results of tested agents (e.g., perindopril in PEPCHF, candesartan in Charm-Preserved, irbesartan in I-Preserved, spironolactone in TOPCAT) have been largely disappointing. Only the hospitalization rate could be significantly reduced, e.g. in TOPCAT [8] (p=0.04). The results also appear to be origin-dependent (non-prespecified outcome for the US collective showed significant improvement in hospitalization and mortality).

Finally, Daniel Franzen, MD, Clinic for Pneumology, UniversitySpital Zurich, gave an insight into the pneumological side of the condition. In principle, the time course in the medical history is decisive: Acute dyspnea is most often caused by pulmonary edema, chronic forms indicate mainly asthma, but also COPD. In the clinic, spirometry is helpful, from which the FEV1 value can be derived. In addition, the differential diagnosis of chronic lung disease can be further narrowed with body plethysmography and CO diffusion measurement. In the laboratory, on the other hand, arterial blood gas analysis is performed very frequently, and in imaging, X-ray and CT thorax are used if necessary.

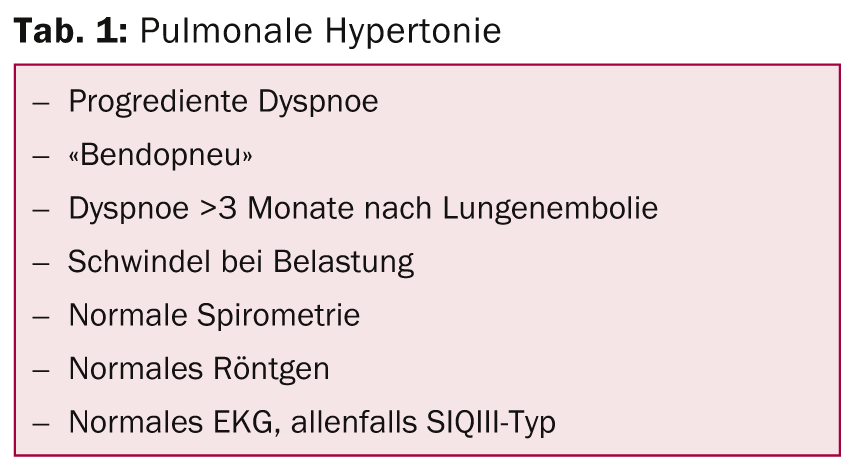

“There are very effective treatment options for many chronic lung diseases with dyspnea: for pulmonary fibrosis, for example, pirfenidone [9] (although the only therapy with mortality benefit remains lung transplantation) and for pulmonary emphysema, surgical or bronchoscopic lung volume reduction or lung transplantation.” If the baseline examination is largely unremarkable, pulmonary hypertension should be considered in the presence of chronic dyspnea (Tab.1).

If dyspnea persists for several months after acute pulmonary embolism, consider chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). “Psychogenic causes should not be forgotten either; after all, dyspnea is still defined as a subjectively perceived feeling of difficult breathing or air hunger and not primarily as hyperpnea, hypopnea, tachypnea, bradypnea, etc.,” the speaker warned.

Source: 19th Zurich Cardiovascular Day, December 4, 2014, Zurich

Literature:

- Tonelli M, et al: Lancet 2012 Sep 1; 380(9844): 807-814.

- Hillege HL, et al: Circulation 2006 Feb 7; 113(5): 671-678.

- Montalescot G, et al: Eur Heart J 2013 Oct; 34(38): 2949-3003.

- Cheng VY, et al: Circulation 2011 Nov 29; 124(22): 2423-2432, 1-8.

- Teerlink JR, et al: Lancet 2013 Jan 5; 381(9860): 29-39.

- McMurray JJV, et al: N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 993-1004.

- Ruschitzka F, et al: N Engl J Med 2013 Oct 10; 369(15): 1395-1405.

- Pitt B, et al: N Engl J Med 2014 Apr 10; 370(15): 1383-1392.

- Noble PW, et al: Lancet 2011 May 21; 377(9779): 1760-1769.

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(1): 33-35