Hardly any patients report it, but many suffer from it: Tumor breakthrough pain. The sudden attacks of pain are a psychological and physical burden for those affected, which severely restricts their quality of life. In addition, tumor breakthrough pain causes considerable costs due to increased use of medical services. Quick help is needed here.

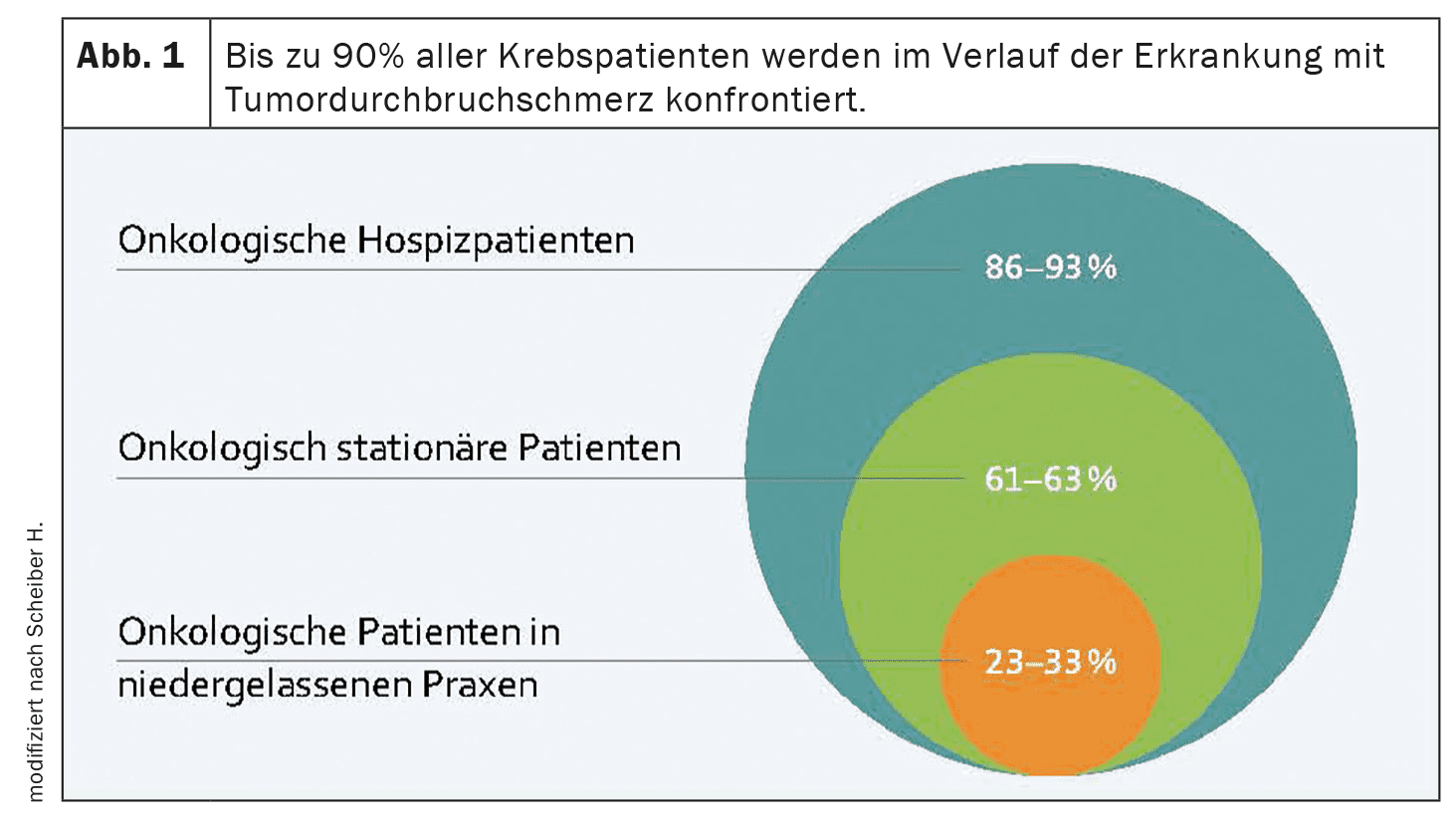

(red) Almost none of the oncology patients are spared tumor-related breakthrough pain during the course of their disease. Depending on how advanced the disease is, the prevalence is 23-89%. Around one in three oncology patients undergoing outpatient treatment report breakthrough pain. Among inpatient cancer patients, it is one in two and among hospice patients, 9 out of 10 report experiencing breakthrough pain (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, too little focus is often placed on this phenomenon – perhaps also because there is no generally accepted definition of breakthrough pain in tumor patients. According to the German Society for Pain Medicine, it is a temporary pain exacerbation that occurs despite adequate control of the permanent pain. Typical for tumor breakthrough pain is the sudden onset of pain, a short duration of pain, as well as the high intensity of pain, which is described as devastating or unbearable. In addition, the pain increases rapidly, reaches its maximum after 3-5 minutes and rarely lasts longer than half an hour. The frequency of breakthrough pain attacks varies significantly between patients, with episodes occurring a median of 2-6 times per day.

A distinction is made between idiopathic and incidental pain. This distinction is important because different medication may be used for exercise-induced breakthrough pain than for spontaneous/idiopathic breakthrough pain. Predictable or incidental breakthrough pain can be triggered by voluntary (e.g. lifting or walking), involuntary (e.g. coughing or urinating) or procedure-dependent events (e.g. medical or nursing interventions). Preparations that reach their maximum effect after a delay, such as liquid morphine sulphate in a single-dose container, can be used here. In the case of spontaneous pain, on the other hand, it is essential to use medication that acts quickly.

Recognizing and treating breakthrough pain

Many patients do not report the extent of their pain in detail. It would therefore be ideal if the pain were recorded in a pain diary. In addition to the frequency and intensity of the pain, the accompanying circumstances and potential triggers can also be recorded. Otherwise, standardized questionnaires such as the “Brief Pain Inventory” or the “Breakthrough Pain Assessment Tool” (BAT) are available.

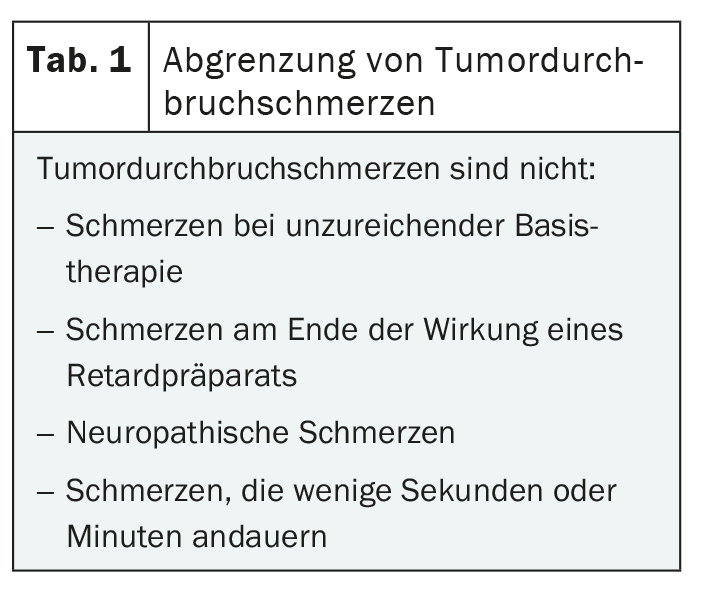

In terms of differential diagnosis, attention must be paid to inadequate analgesic dosing of the basic medication, individually incompatible opiates and an excessively long dosing or administration interval (Table 1). The latter is often the case with round-the-clock analgesia. This “end-of-dose” pain then always occurs shortly before the next planned dose.

The therapy depends on the underlying pain mechanisms. The type of pain should also be taken into account when choosing medication. In principle, opioids, non-opioids and co-analgesics can be considered for the treatment of tumor-related breakthrough pain. The form of administration – intravenous, oral, rectal, sublingual, transmucosal, subcutaneous or local – should be tailored to the needs and preferences of the individual patient and their care situation. An ideal preparation for the treatment of tumor breakthrough pain should have a rapid onset of action, high analgesic potency, short duration of action and ease of administration. Fast-acting fentanyl is therefore recommended as an on-demand medication. It can very quickly and over a sufficiently short period of time reduce the pain peaks in the event of unpredictable breakthrough pain.

Further reading:

- Müller-Schwefe G, et al: Fast-acting fentanyl in the treatment of breakthrough pain in oncology patients. 2011; 3(5): 1-16.

- Portenoy RK, Hagen NA: Breakthrough pain: definition, prevalence and characteristics. Pain 1990; 41(3): 273-281.

- Überall MA, Müller-Schwefe GHH: Sublingual fentanyl orally disintegrating tablet in daily practice: efficacy, safety and tolerability in patients with breakthrough cancer pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2011; 27(7): 1385-1394.

- Fortner BV, et al: Description and predictors of direct and indirect costs of pain reported by cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003; 25(1): 9-18.

- Portenoy RK, et al: Breakthrough pain in community-dwelling patients with cancer pain and noncancer pain, part 2: impact on function, mood, and quality of life. J Opioid Manag 2010; 6(2): 109-116.

- Greco MT, et al: Epidemiology and pattern of care of breakthrough cancer pain in a longitudinal sample of cancer patients: results from the Cancer Pain Outcome Research Study Group. Clin J Pain 2011; 27(1): 9-18.

- Everywhere MA: DGS practice guideline Tumor-related breakthrough pain: Version: 2.0 for healthcare professionals. Aids for daily practice. 2021.

- Vellucci R, et al: What to Do, and What Not to Do, When Diagnosing and Treating Breakthrough Cancer Pain (BTcP): Expert Opinion. Drugs 2016; 76: 315-330.

- Webber K, et al: Development and validation of the breakthrough pain assessment tool (BAT) in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 48(4): 619-631.

- Mercadante S, et al: Breakthrough pain and its treatment: critical review and recommendations of IOPS (Italian Oncologic Pain Survey) expert group. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24(2): 961-968.

- Davies AN, et al: Breakthrough cancer pain (BTcP) management: a review of international and national guidelines. BMJ Support Palliative Care. 2018; 8(3): 241-249.

- Jara C, et al: SEOM clinical guideline for treatment of cancer pain (2017). Clin Transl Oncol 2017; 20(1): 97-107.

- Scheiber H: Fast-acting fentanyl for tumor breakthrough pain. CME publishing house 2019.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2024; 12(4): 32-33