Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) reduces the life expectancy of affected patients and often drastically limits their quality of life. Early diagnosis is extremely important, because today a targeted therapy is available in the form of eculizumab, which significantly improves the prognosis. Unfortunately, PNH symptoms are nonspecific. Primary care providers can still do much to speed diagnosis by thinking about the clinical picture of PNH.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare disorder of hematopoiesis. Due to an acquired, non-heritable gene mutation in the hematopoietic stem cells, the cell surfaces of the erythrocytes lack certain proteins that protect the blood cells from attack by the complement system. As a result, the erythrocytes are destroyed intravasally.

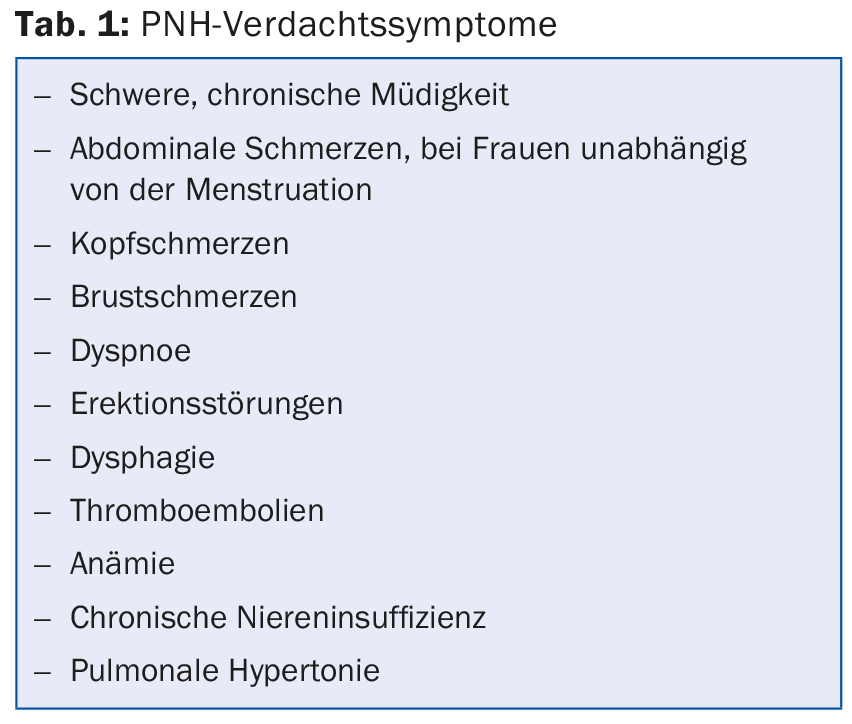

PNH causes multiple but only nonspecific symptoms. Typical symptoms are chronic fatigue, abdominal, head and chest pain, dyspnea, dysphagia and, in men, erectile dysfunction (tab. 1) . Because these symptoms are so nonspecific, patients often receive inadequate and untargeted treatment for months and years. This is fatal because the disease is chronically progressive and the risk of complications increases with the duration of the disease.

High mortality and morbidity

As a result of chronic hemolysis, iron overload and liver and kidney damage may occur. In addition, PNH is associated with thrombophilia, which greatly increases the risk of thromboembolic events: 28-49% of all PNH patients experience at least one thromboembolism during the course of the disease, with corresponding consequences such as cerebral stroke, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, abdominal ischemia, deep vein thrombosis, etc. Thromboembolism is also the most common cause of death in patients with PNH, the second most common being chronic renal failure. 35% of PNH patients die within the first five years of diagnosis, 50% within the first ten years. Patient morbidity is often significant due to chronic fatigue and pain, and many experience frequent hospitalizations and work disability.

Diagnostics: anemia is not always present

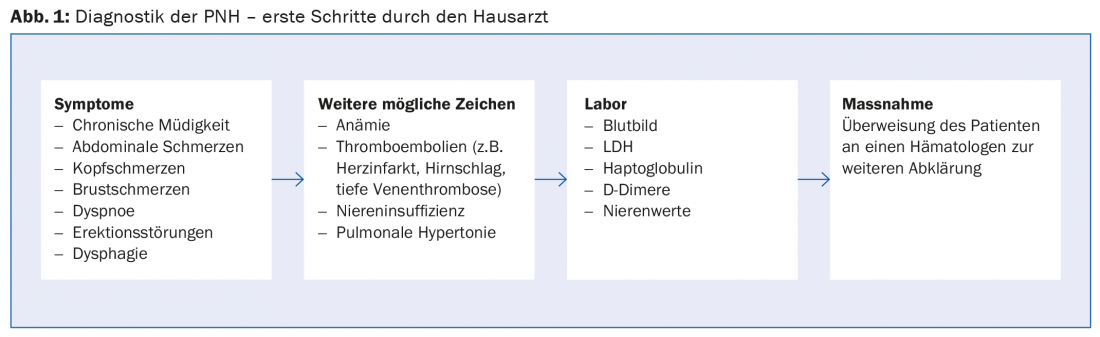

Because PNH is very rare and symptoms are nonspecific, it often takes years to make a correct diagnosis. To make the diagnosis, primary care providers need to do one thing above all: think about the possibility of PNH! If there are suspicious symptoms or If diseases are present, the following clarifications in the laboratory are advisable:

- LDH: concentration increased

- Haptoglobin: concentration decreased

- D-dimers: concentration increased during thromboembolic events

- Anemia is sometimes present, but not always!

If PNH is suspected, the patient should be referred to a hematologist (Fig. 1) . The gold standard for confirming a diagnosis of PNH is flow cytometric analysis of erythrocytes and granulocytes in a peripheral blood sample to demonstrate the absence of surface proteins on the blood cells.

Therapy with Eculizumab

Supportive measures such as transfusions, analgesics, and anticoagulation are used to treat PNH. For some years now, in Switzerland since 2010, a targeted therapy has also been available in the form of eculizumab (Soliris®). Eculizumab is a monoclonal antibody against complement factor C5. Treatment with eculizumab reduces intravascular hemolysis and dramatically lowers the risk of thromboembolism in PNH patients.

These effects have a decisive impact on the prognosis of PNH patients: studies show that their life expectancy increases significantly with eculizumab treatment: The 5-year survival rate is 95.5% in treated patients and 66.8% in non-treated patients. The treated patients thus achieve a life expectancy that no longer differs from that of the general population.

In Switzerland, the indication for therapy must be given in a university hospital or in one of the cantonal hospitals Aarau, Bellinzona, Lucerne, or St. Gallen can be provided. The controls of patients in the context of registries must also take place in these centers. Administration of eculizumab between these controls may be done at a local hospital.

Further reading:

- Swiss Compendium of Medicinal Products, Specialist Information Soliris.

- Audebert HJ, et al: J Neurol 2005; 252(11): 1379-1386.

- Borowitz MJ, et al: Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2010; 78(4): 211-230.

- Brodsky RA: PNH. Hematol. Basic Princ. Pract. 4th Ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005; 419-427.

- Federal Office of Public Health, Soliris Specialty List.

- Gerber B, et al: BMJ Case Rep 2011; 2011.

- Hill A, et al: Br J Haematol 2010; 149(3): 414-425.

- Hill A, et al: Br J Haematol 2007; 137: 181-192.

- Hill A, et al: Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2006; 108: 985.

- Hill A, et al: Blood 2013; 121(25): 4985-4996, quiz 5105.

- Hillmen P, et al: Blood 2007; 110(12): 4123-4128.

- Hillmen P, et al: Am J Hematol 2010; 85(8): 553-559.

- Hillmen P, et al: Br J Haematol 2013; 162(1): 62-73.

- Hillmen P, et al: N Engl J Med 1995; 333(19): 1253-1258.

- Kelly RJ, et al: Blood 2011; 117(25): 6786-6792.

- Lee JW, et al: Int J Hematol 2013; 97(6): 749-757.

- Meyers G, et al: Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2007; 110: 3683.

- Moyo VM, et al: Br J Haematol 2004; 126(1): 133-138.

- Parker C, et al: Blood 2005; 106(12): 3699-3709.

- Rother RP, et al: JAMA 2005; 293(13): 1653-1662.

- Schrezenmeier H, et al: Haematologica 2014; 99(5): 922-929.

- Socié G, et al: Lancet 1996; 348(9027): 573-577.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(4): 25-26