Sleep disorders are part of everyday life for a large proportion of the older population. A change in sleep architecture and a reduced need for sleep are natural. So when should we start talking about insomnia? And how can those affected be helped effectively beyond self-medication?

Sleep disorders in old age or when will sleep be like in childhood again? This question is asked – unconsciously or consciously – by many patients who suffer from sleep disorders in old age, and it needs to be answered. As we age, less sleep and a changed sleep architecture with a higher proportion of light sleep is natural and healthy – that is, we all experience a changing sleep pattern in structure and duration over the lifespan. The first goal of sleep-specific diagnostics in old age is to differentiate a subjective from an objectifiable sleep disorder and to understand the sleep disorder as a cause or consequence of an impaired quality of life, an organic disease, an increased psychological stress or as a symptom of an anxiety, affective or neurodegenerative disease.

Epidemiology and challenges of sleep disorders in the elderly.

Sleep disturbances in the elderly are a relevant health problem in one-third to one-half of the population and are associated with decreased quality of life, increased psychological distress, and depressive disorders [1,2]. Self-medication is common, accounting for 49% of those affected, and not infrequently leads to a dependence syndrome on benzodiazepines, Z-substances, and/or alcohol [3]. Cohort data from the USA with more than 9000 participants show that 57% of the older population (≥65 years) suffer from chronic insomnia – i.e. a sleep disorder that lasts at least 3 months or longer – and 25% of those affected sleep during the day [4,5]. It often takes a long time until a diagnosis is made by a sleep-specific stage diagnosis and therapy is initiated: 80% of those affected suffer from chronic insomnia (≥3 months) at diagnosis and 25% have been suffering from their sleep disorder for more than 10 years [6].

Physiological change of sleep in old age

Growing older does not mean suffering from insufficient and/or non-restorative sleep. However, sleep duration and sleep architecture-four cyclically recurring sleep stages of 90 minutes each with non-REM (sleep stages N1, N2, and N3) and REM sleep-change physiologically across the lifespan [2]. While children sleep an average of 10 to 14 hours and young adults 6.5 to 8.5 hours per night, the average sleep duration decreases to 5 to 7 hours of sleep per night after the age of 60 [7]. With increasing age, not only the duration of sleep decreases, but the latency to fall asleep increases, the proportion of light sleep (non-REM N1 and N2) increases, and the REM sleep proportion per night shortens. These age-related and physiological changes can lead to anxiety if sleep expectations are unrealistic and can trigger or aggravate insomnia by worrying [2]. In the second half of life, two thirds of our sleep is superficial with 66% light sleep (Non-REM N1: 18%; N2: 48%), followed by 16% deep sleep (Non-REM N3) and 18% dream sleep (REM), so that the subjective perception of less deep sleep corresponds to the physiology of sleep in old age, usually has no disease value and only the preoccupation with the altered sleep, can trigger an insomnia [2,8]. Another factor that impairs sleep quality in old age is the reduced sleep pressure due to the loss of natural timers, such as regular working hours, regular meals and a reduced increase in tiredness during the course of the day due to reduced daytime activity and/or “daytime naps”; the result is reduced deep sleep with a reduced proportion of slow wave sleep (SWS) [8]. If we can explain the changes in sleep physiology in old age to our patients, the level of suffering and expectations are often reduced and the impending vicious circle of non-organic insomnia can be broken at an early stage.

Gender-specific sleep disorders

Gender differences in frequency and type of sleep disorders are relevant. Women have a 40% higher risk of developing insomnia and are two times more likely to suffer from restless legs syndrome than men. In contrast, 50% more men than women suffer from obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) as summarized in the Society for Women’s Health research report [9]. Compared to females aged 18 to 39, women are twice as likely to suffer from difficulty falling asleep from the 6th decade of life onwards, while problems sleeping through the night and the use of sleeping pills increase with age in both sexes [10].

Sleep disturbances and risk for cognition disorders

Sleep disorders are relevant in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and are often associated with aggressive behavior, sleep fragmentation and a disturbed day-night rhythm, including the Sundowning phenomenon – unusual, restless and/or aggressive behavior in the early evening hours – which is why not only the patients themselves but also their caregivers are burdened and these complex sleep disorders often lead to early institutionalization of the patients [11,12]. The Swiss HypnoLaus study was able to prove that older patients over the age of 65 with cognitive disorders (Mild Cognitive Impairment) suffer from altered sleep architecture, lower sleep efficiency and more frequent sleep-related breathing disorders [13]. Today, we know that sleep disturbance is not only an accompanying phenomenon or consequence of dementia pathology, but itself increases the risk of cognition impairment and/or AD by 1.68-fold [14], so there is a bidirectional relationship between sleep and cognition disturbance [15]. Patients with longstanding insomnia in the 5. until 6th decade of life have a reduced nocturnal amyloid-β clearance via the glymphatic system, so that the increased amyloid-β aggregation in the brain results in a higher risk of dementia [16], and sleep disorders are considered an independent risk factor for cognitive disorders, especially in the domains of attention, episodic memory, working memory and executive functions [17]. Thus, early detection of the sleep disorder and its sufficient treatment is essential to maintain or improve cognition as well as the quality of life of patients/patients and their families during aging and to reduce the risk of dementia.

Benzodiazepines and Z-substances

A particular problem in the elderly is the harmful use of or dependence on benzodiazepines and Z-substances, the latter substances being non-benzodiazepine agonists such as zolpidem, zopiclone, and zaleplon with short half-lives and also high potential for tolerance and dependence. There is now clear evidence that long-acting hypnotics at high doses increase the risk of dementia [18]. Besides cognition disorder with increased risk of dementia, Z-substances and benzodiazepines potentiate with age the risk of falls, mortality, disrupt sleep architecture, lead to non-restorative sleep, trigger rebound insomnia or even anxiety and agitation by paradoxical effect, which is why it is not uncommon to increase the dose [19]. This vicious circle can be broken by qualified benzodiazepine withdrawal only with difficulty and over a long period of time in an inpatient gerontopsychiatric setting with pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy offers in individual and group settings. Because the benzodiazepines and Z-substances have a high potential for dependence after only 3 to 4 weeks, the authors recommend against using these substances, especially in the outpatient setting. Especially in old age, the altered metabolism must be considered, so that in Switzerland a dose adjustment to 50% is recommended for Z-substances from the age of 65. In addition, women metabolize Z-substances 50% more slowly than men, so adverse effects are sex- and age-specific, and women are at particularly high risk for adverse effects from benzodiazepines and Z-substances as they age [20].

Recognizing primary and secondary insomnia: interdisciplinary step-by-step diagnostics

Diagnosis of primary and secondary insomnia can enable early and specific therapy through sleep-specific history questions and specific stage diagnostics, thus reducing the risk of sequelae and improving the quality of life of those affected [6]. Patients/patients either do not report their sleep disorder at all or present because of their sleep disorder, as it is considered a less stigmatizing symptom, but not infrequently couples a serious psychiatric illness. Therefore, the authors recommend routinely asking about sleep in all patients and evaluating mood, psychotic symptoms, and suicidality in cases of insomnia.

The definition of primary non-organic insomnia according to ICSD-3 and ICD-10.

Primary insomnia is defined by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) as a disorder of falling asleep or staying asleep that occurs at least three times a week for a period of at least one month and that impairs the patient in important areas of life [21]. Chronic insomnia exists when the sleep disturbance persists for at least 3 months. For a diagnosis of primary insomnia, i.e., nonorganic insomnia according to the International Classification of Mental Disorders (ICD-10: F51.0), no somatic or psychiatric disease must cause the sleep disorder, and the insomnia must not be the result of pharmacotherapy or substance use.

Classification of sleep disorders according to ICDS-3

Sleep disorders are divided into 6 main categories according to the American Association of Sleep Medicine (AASM) (ICDS-3), with categories 2–6 being secondary insomnias:

- Insomnia

- Sleep related respiratory disorders

- Central hypersomnia

- Circadian sleep-wake rhythm disorders

- Parasomnias

- Sleep related movement disorders

Primary versus secondary insomnia: a staged diagnosis.

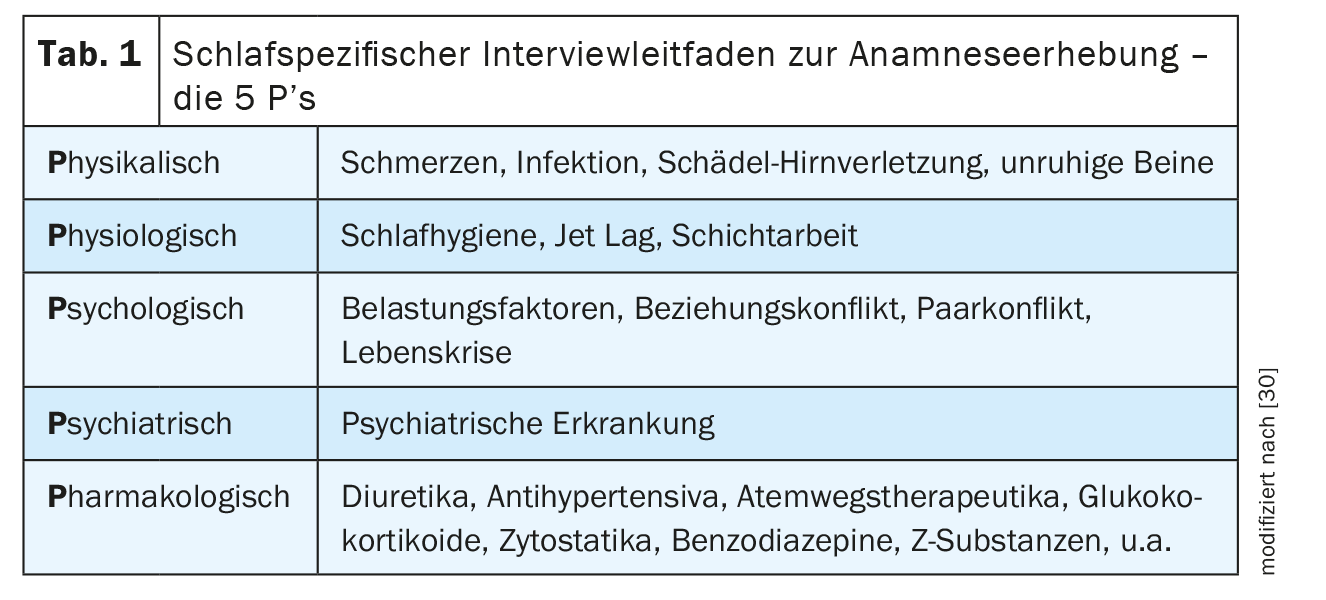

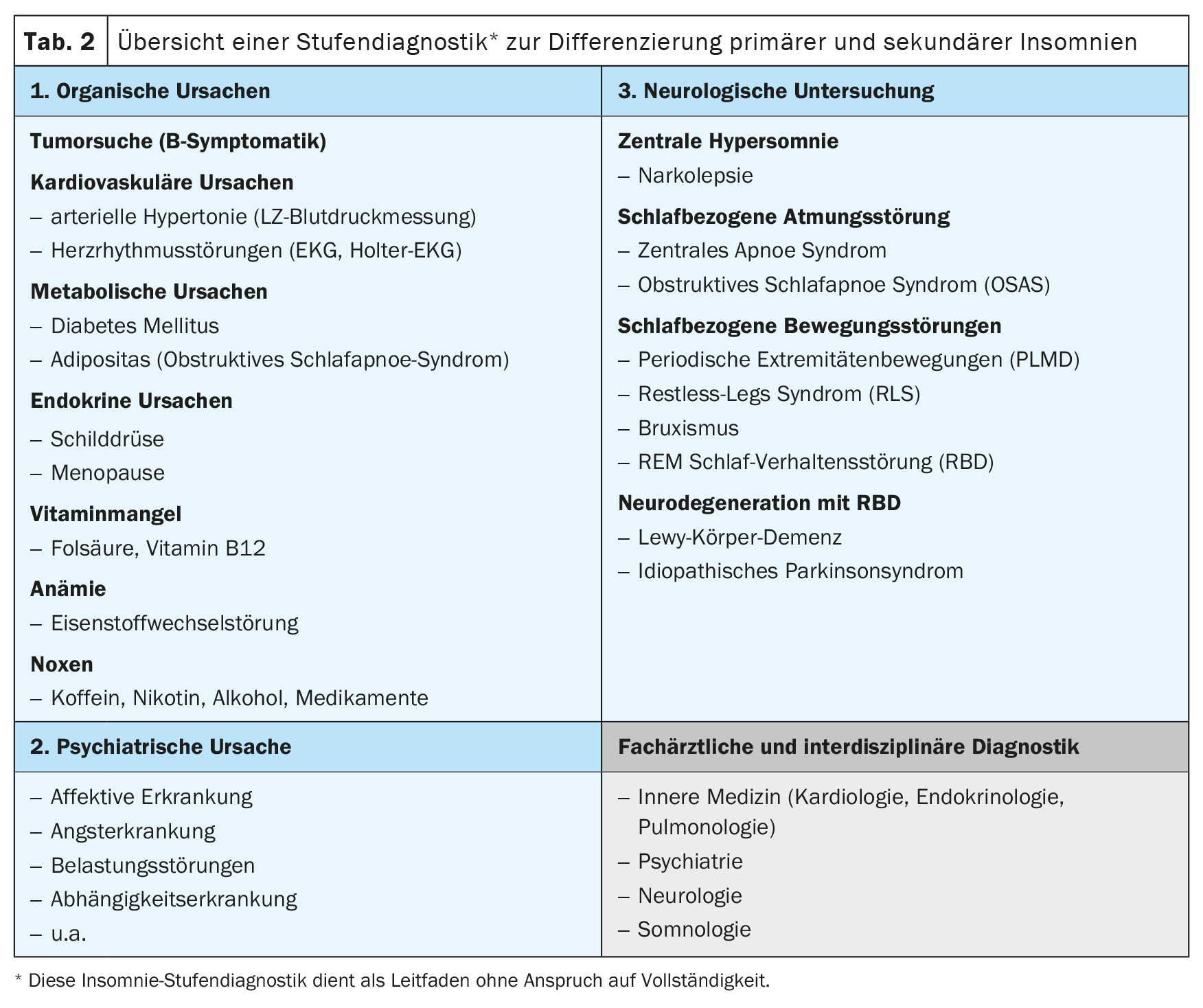

In order to differentiate primary insomnia from secondary insomnia, the “5 P’s” interview guide can be used to systematically record the physical, physiological, psychological, psychiatric and pharmacological causes of insomnia (Table 1) [6]. In the sleep-specific history, a pathological fall asleep latency of ≥30 minutes (normal fall asleep latency 5 to 10 minutes) and/or a sleep-through disorder with single or multiple nocturnal awakenings and the inability to fall asleep again within a few minutes are indicative. Organic causes of insomnia can be detected by a basic GP diagnosis with physical examination, cardiovascular diagnostics including blood pressure measurement, ECG and laboratory diagnostics as well as neurological diagnostics (Tab. 2). If organic causes or daytime sleepiness, morning headaches, concentration disorders, nocturnal brooding, morning low, exhaustion with loss of vitality or anxiety are reported, a sleep-specific and further specialist diagnosis should be made in order to exclude, for example, a sleep-related respiratory or movement disorder, a depressive episode and/or a neurodegenerative disease as causes of secondary insomnia. It is important to ask about the temporal course – with onset and duration, associated stress factors as well as a subjective explanatory model – of the sleep disorder, because an initially non-organic insomnia can cause a depressive episode and, vice versa, the sleep disorder can persist despite remission of the depressive episode and cause a new episode, which is why the treatment of the sleep disorder is of central importance.

Insomnia and neurological diseases

With increasing age, the early detection of secondary insomnia in neurological diseases such as stroke or traumatic brain injury is also relevant and the new recommendations have been published in the revised S2k guideline on insomnia in neurological diseases of the German Neurological Society [22].

Sleep specific diagnostics

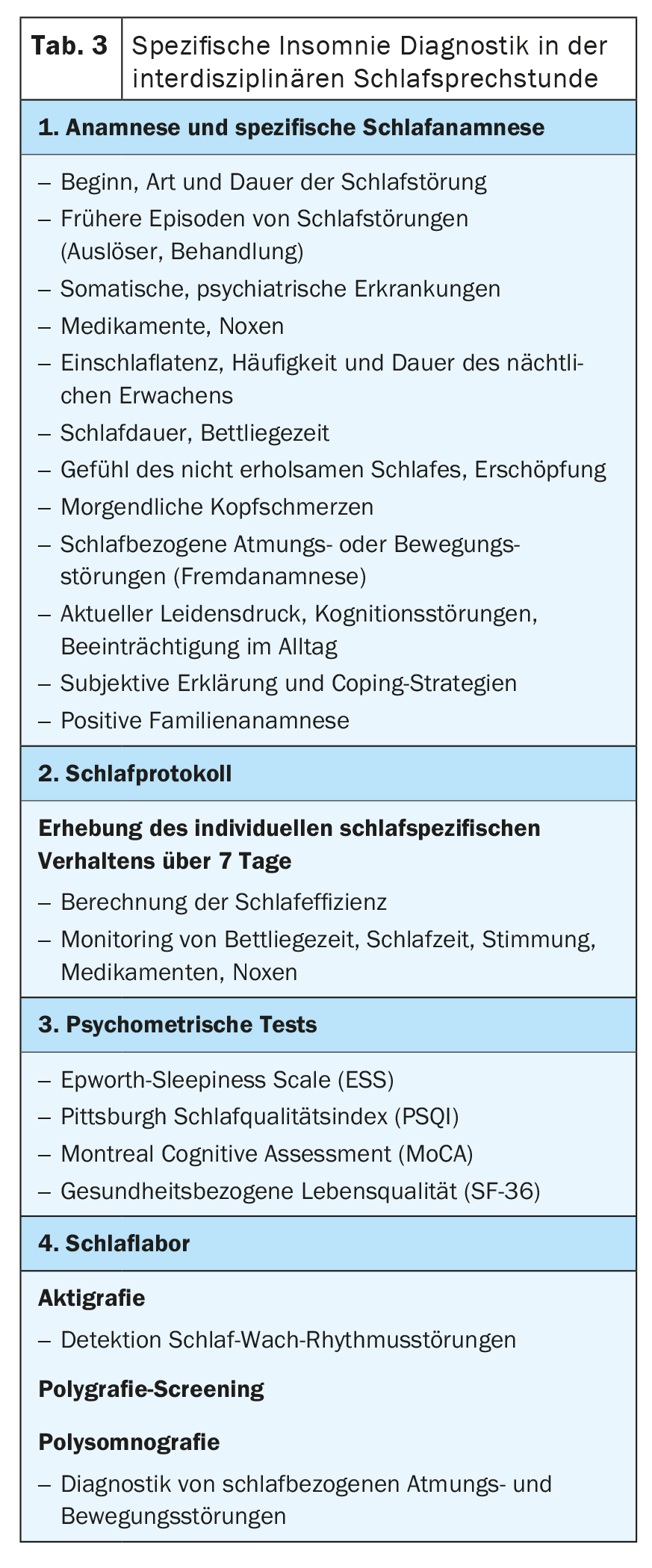

Non-organic, i.e. primary insomnia is diagnosed clinically after exclusion of organic causes. Important sleep-specific anamnesis questions are shown in Table 3. A sleep-specific assessment includes a history, clinical as well as laboratory examination, the collection of sleep-specific psychometric assessments, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), or the collection of a sleep log for at least 7 days. This protocol is completed by the patient in the morning and in the evening and provides information about mood, medication intake and noxious substances as a basis for personalized sleep education of the patient, in addition to monitoring bedtime and sleep time, whereby sleep efficiency can be calculated as a basis for sleep restriction. Furthermore, for the evaluation of cognition, initial dementia screening, e.g. with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), as well as the survey of quality of life (SF-36) is meaningful and relevant for the assessment of progression. In the case of a positive dementia screen, we advise a full workup for cognition impairment or dementia.

Indication of polysomnography

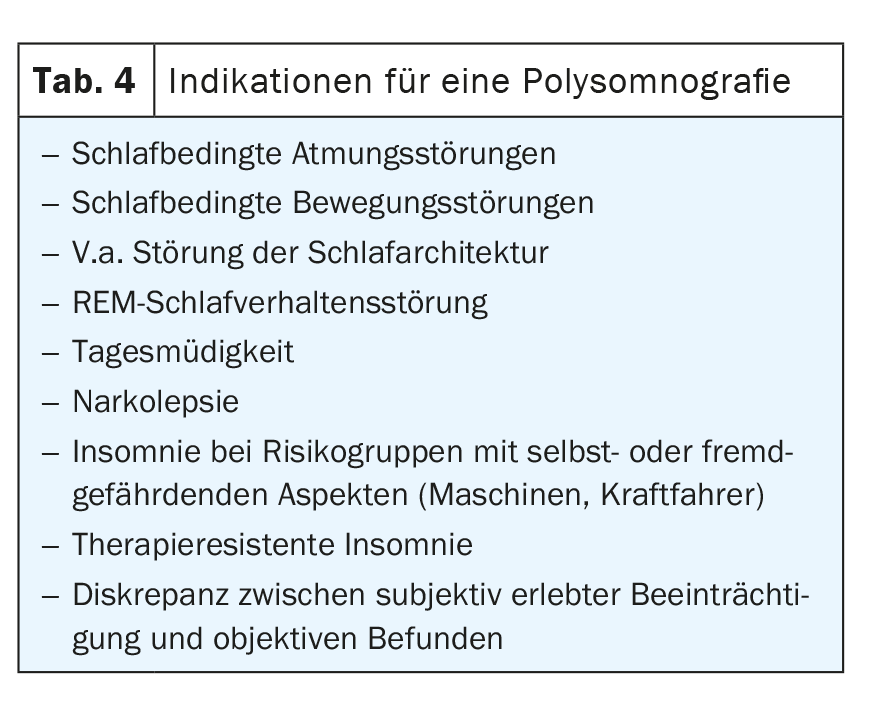

Polysomnography is only indicated in special cases (Table 4) . Sleep-related movement disorders include nocturnal bruxism, periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) and restless legs syndrome (RLS ). RLS may be diagnosed clinically when. 1. There is an urge to move the legs at rest and during relaxation, 2. a circadian rhythm with predominance of symptoms in the evening/at night is noticeable, 3. the improvement of the symptoms occurs with movement, and 4. association with sensory disturbance or pain is reported, and usually does not require polysomnography. Organic causes of RLS, such as polyneuropathy, iron metabolism disorder, and thyroid disease should be excluded by laboratory diagnosis.

How can insomnia be treated in the elderly?

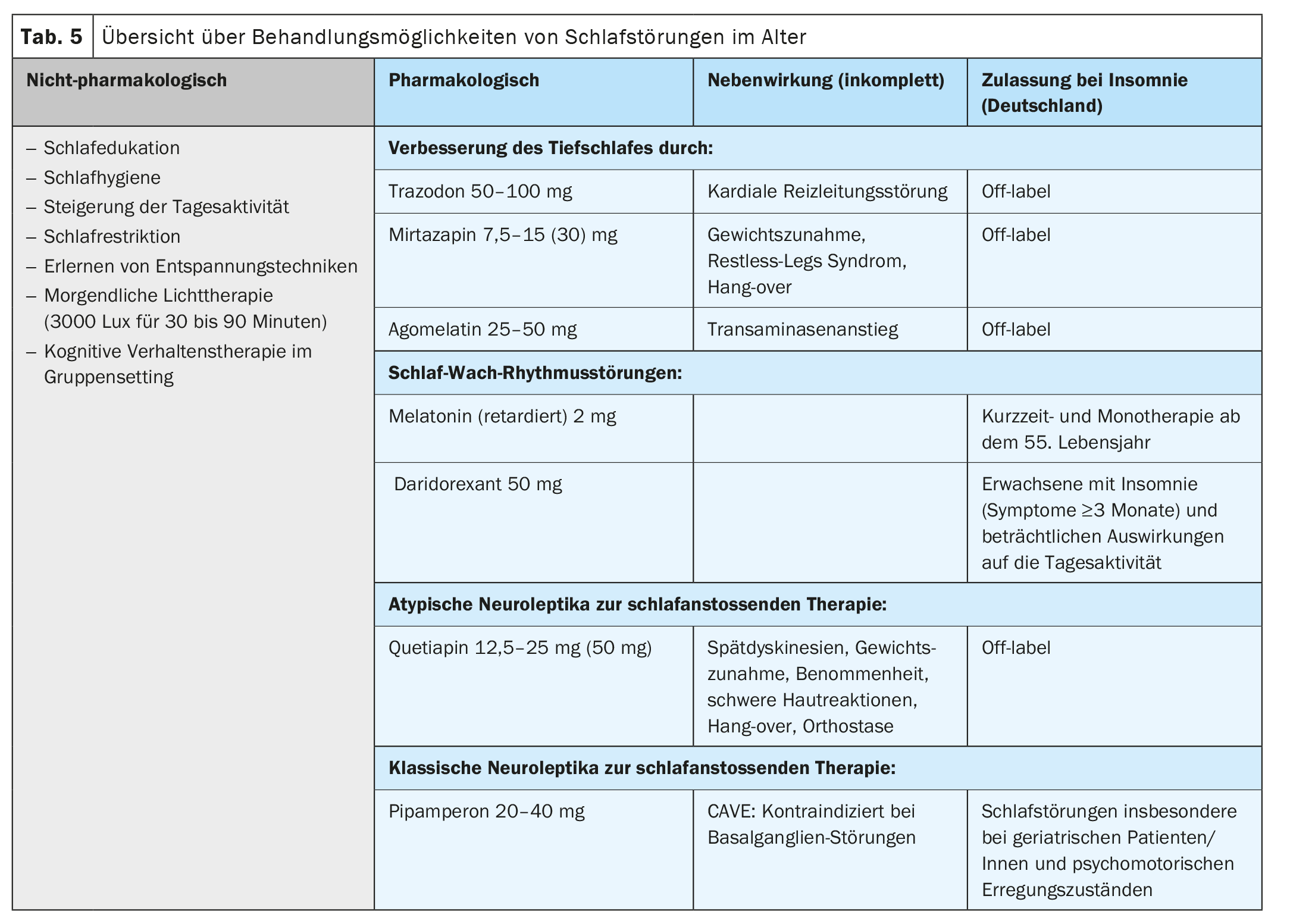

In the treatment of sleep disorders, in addition to pharmacotherapy, non-pharmacological therapies with psychoeducation to improve sleep hygiene, day-night rhythm and daytime activity play an essential role (Tab. 5). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with psychoeducation in a group setting is particularly effective and can also improve sleep quality in older patients over the age of 65. [23,24].

Non-pharmacological therapy

First-line therapy is a non-pharmacological approach using cognitive behavioural therapy to improve and stabilize the patient’s sleep-wake cycle (Table 5) [25]. Psychoeducational group therapy is also effective in improving insomnia and sleep quality in elderly patients/patients [23]. Contents include learning good sleep hygiene with regular day-night rhythm, relaxation techniques, increasing daytime activities, decreasing focus on sleep and feared insomnia, and expanding social activities. Through regular use of a sleep protocol, sleep efficiency can be calculated and through sleep restriction, sleep pressure can be increased as well as sleep quality can be improved. Morning light therapy with 3000 lux for 30 to 90 minutes improves insomnia in neurodegenerative diseases [26], affective disorders [27] and in non-organic insomnia [28]. In dementia, combining light therapy with physical activity by walking for 30 minutes at least 4 days per week improves sleep duration [22].

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy of insomnia in the elderly must take into account undesirable side effects – especially anticholinergic and thus affecting cognition – and altered pharmacokinetics in old age (Tab. 5). The evidence as to whether older patients generally tolerate lower doses of psychotropic drugs is controversial, so we recommend slow dosing with a lower starting dose. The target dose may be based on clinical symptoms. Deep sleep is improved by trazodone, mirtazapine, agomelatine, and St. John’s wort, although St. John’s wort is not recommended by the authors due to CYP3A4 interactions in geriatric medicine because of polypharmacy interactions. Trazodone not only improves sleep, but slows the progression of cognition disorders [29]. Mirtazapine and quetiapine are also effective for sleep induction. All agents are not approved for the sole treatment of insomnia, so off-label education must be provided. Benzodiazepines and Z-substances, although still commonly prescribed, should be avoided in the elderly and used only to avert crisis situations such as acute suicidality for short periods in the inpatient setting.

Forecast

Prognostically, sufficient and early treatment of insomnia is relevant and leads to remission in half of those affected, with men having a higher treatment success compared to women [2]. Residual symptoms often persist and there is an increased risk of relapse. Risk of relapse within 4 years after remission of sleep disturbance is increased by cognition disturbance (HR 1.46), inadequate sleep quality (HR 1.43), impaired mood (HR 1.39), female sex (HR 1.39), sleep-through disturbance (HR 1.35), and fatigue (HR 1.24)-data in parentheses correspond to hazard ratio after controlling for baseline insomnia, severity of depressive disorder, and somatic illness. Sex-stratified subgroup analyses emphasize the increased risk of relapse in men from cognition disturbances (HR 1.98) and in women from sleep-through disturbances (HR 1.46), so the authors recommend paying particular attention to cognition disturbances, sleep-through disturbances, sleep quality, affective symptoms, and signs of fatigue after remission of insomnia.

Conclusion

Sleep disturbance is a symptom with multifactorial etiology and an independent risk factor for cognition impairment and dementia. Therefore, we recommend routine evaluation of sleep to detect primary and secondary insomnia at an early stage, to treat it specifically and in an interdisciplinary manner in order to reduce the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in old age and to maintain and improve the quality of life of the affected persons and their relatives in the long term.

Take-Home-Messages

- Insomnia has a multifactorial genesis and requires an interdisciplinary diagnosis in order to differentiate primary – i.e. non-organic insomnia (ICD-10: F51.0) – from secondary insomnia and to classify it in relation to the physiological changes of sleep in old age.

- With increasing age, less sleep and a changed sleep architecture with two-thirds light sleep is physiological, so that sleep education with explanation of the natural changes of sleep is of high importance.

- Up to 50% of the older population suffers from a sleep disorder with

high proportion of self-medication, late diagnosis, chronicity and risk of dependence on hypnotics and/or alcohol. - Benzodiazepines and Z-substances (non-benzodiazepine agonists zolpidem, zopiclone, zaleplon) should not be used in geriatric and sleep medicine, as they have a high tolerance and dependency potential, increase agitation and anxiety in old age due to paradoxical effects, disrupt sleep architecture, are metabolized up to 50% less by women, and increase the risk of falls and dementia.

- Sleep disorders in the elderly are treated non-pharmacologically and pharmacologically in the context of comorbidities and polypharmacy. Cognitive behavioral therapy is also effective in the elderly in a group setting and focuses on sleep education, improvement of daily activity, correction of sleep hygiene to improve sleep efficiency, sleep quality and quality of life.

Literature:

- 2012 SG. Schlafstörungen in der Bevölkerung. Neuchâtel: Bundesamt für Statistik (BFS); 2015.

- Patel D, Steinberg J, Patel P: Insomnia in the Elderly: A Review. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018; 14: 1017–1024.

- Hersberger KE, Renggli VP, Nirkko AC, et al.: Screening for sleep disorders in community pharmacies – evaluation of a campaign in Switzerland. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2006; 31: 35–41.

- Abad VC, Guilleminault C: Insomnia in Elderly Patients: Recommendations for Pharmacological Management. Drugs Aging. 2018; 35: 791–817.

- Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, et al.: Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. 1995; 18: 425–432.

- Rauen K, Weidt, S: Insomnia – Symptom with multifactorial genesis, diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders. Praxis/Hogrefe. 2017; 106.

- Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV: Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004; 27: 1255–1273.

- Mander BA, Winer JR, Walker MP: Sleep and Human Aging. Neuron. 2017; 94: 19–36.

- Mallampalli MP, Carter CL: Exploring Sex and Gender Differences in Sleep Health: A Society for Women’s Health Research Report. Journal of Women’s Health. 2014; 23: 553–562.

- Schlack R, Hapke U, Maske U, et al.: Frequency and distribution of sleep problems and insomnia in the adult population in Germany: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013; 56: 740–748.

- Moran M, Lynch CA, Walsh C, et al.: Sleep disturbance in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep Med. 2005; 6: 347–352.

- Peter-Derex L, Yammine P, Bastuji H, Croisile B: Sleep and Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep Med Rev. 2015; 19: 29–38.

- Haba-Rubio J, Marti-Soler H, Tobback N, et al.: Sleep characteristics and cognitive impairment in the general population The HypnoLaus study. Neurology. 2017; 88: 463–469.

- Bubu OM, Brannick M, Mortimer J, et al.: Sleep, Cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep. 2017; 40.

- Ju Y-ES, Lucey BP, Holtzman D: Sleep and Alzheimer disease pathology – a bidirectional relationship. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014; 10: 115-119.

- Musiek ES, Xiong DD, Holtzman DM: Sleep, circadian rhythms, and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Experimental & molecular medicine. 2015; 47: e148-e48.

- Fortier-Brochu E, Beaulieu-Bonneau S, Ivers H, Morin CM: Insomnia and daytime cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2012; 16: 83-94.

- Chen PL, Lee WJ, Sun WZ, et al: Risk of dementia in patients with insomnia and long-term use of hypnotics: a population-based retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e49113.

- Savaskan E: Benzodiazepin-Abhängigkeit im Alter: Wie geht man damit um? Praxis. 2016; 105: 637–641.

- Cubała WJ, Wiglusz M, Burkiewicz A, Gałuszko-Wegielnik M: Zolpidem pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in metabolic interactions involving CYP3A: sex as a differentiating factor. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010; 66: 955; author reply 57–58.

- (AASM) AAoSM. International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) 2014.

- Mayer G: S2k guideline: Insomnia in neurological diseases: German Society of Neurology (DGN); 2020 [Version 3: 03/02/2020: Available from: https://dgn.org/leitlinien/ll-030-

045-insomnie-bei-neurologischen-erkrankungen-2020 - Lovato LC, Wallace RB, Leng X, et al: Sleep duration, cognitive decline, and dementia risk in older women. Alzheimers Dement. 2016; 12: 21-33.

- Sadler P, McLaren S, Klein B, et al: Cognitive behavior therapy for older adults with insomnia and depression: a randomized controlled trial in community mental health services. Sleep. 2018; 41.

- Zdanys KF, Steffens DC: Sleep Disturbances in the Elderly. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2015; 38: 723-741.

- Amara AW, Chahine LM, Videnovic A: Treatment of Sleep Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2017; 19: 26.

- Penders TM, Stanciu CN, Schoemann AM, et al.: Bright Light Therapy as Augmentation of Pharmacotherapy for Treatment of Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016; 18.

- van Maanen A, Meijer AM, van der Heijden KB, Oort FJ: The effects of light therapy on sleep problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2016; 29: 52–62.

- La AL, Walsh CM, Neylan TC, et al.: Long-Term Trazodone Use and Cognition: A Potential Therapeutic Role for Slow-Wave Sleep Enhancers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019; 67: 911–921.

- Schwerthöffer D: Differentialdiagnostik der Insomnie. Sleep Medicine Center Munich: 2008.

InFo NEUROLOGIE & PSYCHIATRIE 2024; 22(2): 18–23