History: The girl in Figures 1 and 2 first presented to our pediatric dermatology consultation at four weeks of age. At birth, he said, only very discrete whitish spots with single red “veins” were noticeable on the left shoulder and the left side of the face. At the end of the second week of life, rapidly increasing red plaques had developed in the area of the formerly whitish lesions.

Personal history: pregnancy, delivery and primary adaptation were unremarkable. Birth weight, length and head circumference were each at the 50th percentile. Percentile. Newborn screening revealed congenital hypothyroidism. Under immediately initiated substitution with L-thyroxine, the newborn has developed very well so far. Family history was unremarkable.

Findings: Four-week-old, rosy-cheeked infant in very good general condition, weight 3940 g. Teleangiectatic plaques with bright red, soft, grouped papules in the area of the left cheek, on the chin, lower lip, neck, high-occipital as well as over the left scapula. The other internal and neurological examination findings were unremarkable.

Quiz

What course of action would you recommend?

A Immediate ophthalmologic examination and cranial MRI at three to four months of age to rule out Sturge-Weber syndrome.

B If the child is in good general condition, continue to wait for the spontaneous course.

C If blood pressure and ECG are unremarkable, initiate beta-blocker therapy immediately.

D Urgent cranial MRI/MRA, ophthalmologic diagnosis, and echocardiography before further therapeutic steps.

Discussion: The correct answer is D. Already the history with clear dynamics within the first weeks of life, starting from barely visible whitish patches with single telangiectasias (so-called precursor lesions) to the formation of rapidly proliferating, erythematous and hyperthermic plaques, leads us to the diagnosis of infantile hemangioma. The clinical findings of our little patient can be classified as segmental hemangiomas or plaque-type hemangiomas due to the distribution pattern and the already initially large area.

As an important differential diagnosis of red spots on the face, capillary malformations (port-wine stains), quite unlike infantile hemangiomas, are already present in full expression at birth.

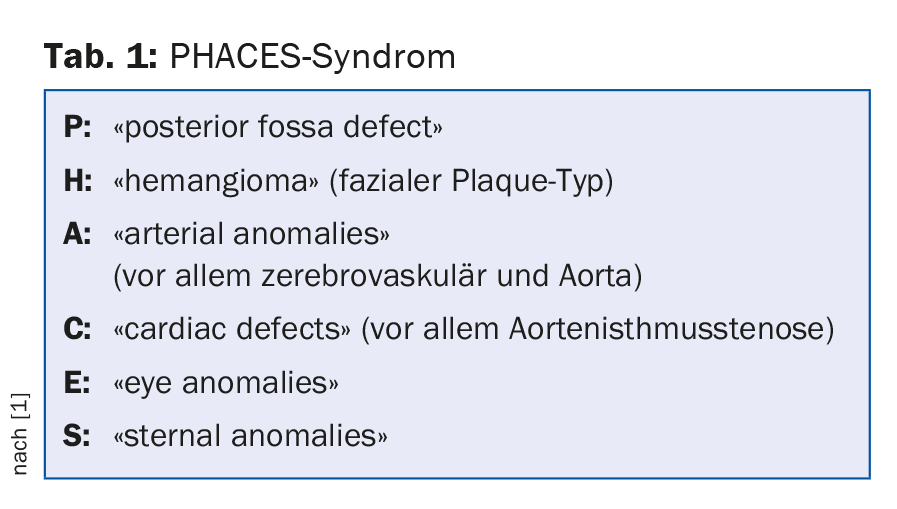

With hemangiomas of this type in the head/neck region, the possibility of a PHACES syndrome (Table 1) must always be considered, which includes a wide spectrum of associated malformations, especially cardiac, vascular, and cerebral anomalies [1].

In more than 30% of cases, matching hemangiomas are found to have at least one, but usually multiple, extracutaneous manifestations of PHACES syndrome [1,2].

From the possible associated anomalies, see Table 1, the temporal urgency of further diagnostics can also be derived (answer D!), which, in addition to an echocardiography, includes an MRI/MRA of the skull and neck, a TSH determination, and an ophthalmologic examination, before the start of a usually necessary beta-blocker treatment [1].

The most common of these are cerebral vascular anomalies, followed by cardiac malformations, especially aortic isthmic stenosis [3]. In our patient, with evidence of hypoplasia of the left common carotid artery and left middle cerebral artery according to the diagnostic criteria of Metry et al. [1] a PHACES syndrome could be confirmed.

Thyroid agenesis detected sonographically as the cause of the abnormal newborn screening can also be assigned to the spectrum as a rare midline defect [4].

The incidence of PHACES syndrome is not yet precisely known, but it appears to be significantly more common than Sturge-Weber syndrome, which is certainly more common. Girls are affected in over 90% of cases [5]. The genetic cause is not yet known, a somatic mutation is discussed.

Infantile hemangiomas are characterized by their typical growth behavior:

- Not present at birth or present only as a precursor lesion

- Proliferation phase from second to sixth week with rapid volume increase over three to nine months

- Plateau phase

- Spontaneous regression approximately from the second year of life over several years.

Particularly in the face, attention should be paid to the possible functional impairment due to expansive growth, especially in hemangiomas in the periorbital region and centrofacially including. Lip with early tendency to ulceration. Plaque-like hemangiomas on the chin and mandible (“beard region”) and jugulum (Fig. 2) may further be warning signs of associated upper airway hemangiomas. During close monitoring in the first three months of life, special attention must be paid to symptoms such as hoarseness, croup symptoms and stridor as signs of subglottic hemangioma.

Ideally, facial hemangiomas should be evaluated at specialized centers as early as possible, at the onset of the proliferative phase, and treated with systemic beta-blockers (propranolol). In patients with PHACES syndrome, some precautions must be taken in this regard [6]. If imaging shows evidence of vascular and/or cerebrovascular abnormalities, these should be discussed on an interdisciplinary basis with regard to a possible strokes situation inducible by blood pressure fluctuations.

In our patient, with knowledge of hypoplasia of the left common carotid artery and left middle cerebral artery, a very cautious and slowly titrated dose increase was performed under close inpatient monitoring. Attention continues to be paid to good hydrogenation.

Propranolol therapy, which has been tolerated without any problems so far, showed a very rapid response (Fig. 3) and is expected to be continued until approximately 12 months of age.

At the age of six months, our patient shows very advanced psychomotor development. Because a certain proportion of patients with PHACES syndrome, especially those with supratentorial structural cerebral anomalies, may show developmental abnormalities during their course, careful pediatric developmental monitoring should continue [7].

Literature:

- Metry D, et al: Consensus Statement on Diagnostic Criteria for PHACE Syndrome. Pediatrics 2009; 124(5): 1447-1456.

- Haggstrom AN, et al: Prospective study of infantile hemangiomas: clinical characteristics predicting complications and treatment. Pediatrics 2006 Sep; 118(3): 882-887.

- Haggstrom AN, et al: Risk for PHACE syndrome in infants with large facial hemangiomas Pediatrics 2010 Aug; 126(2): e418-426.

- Carinci S, et al: A case of congenital hypothyroidism in PHACE syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2012; 25(5-6): 603-605.

- Frieden I, et al: PHACE syndrome. The association of posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities. Arch Dermatol 1996 Mar; 132(3): 307-311.

- Höger PH, et al: Treatment of infantile haemangiomas: recommendations of a European expert group. Eur J Pediatr 2015 Jul; 174(7): 855-865.

- Tangtiphaiboontana J, et al: Neurodevelopmental abnormalities in children with PHACE syndrome. J Child Neurol 2013 May; 28(5): 608-614.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2015; 25(4): 36-38