Despite all medical advances, corrected congenital heart defects (AHF) are not “cured” heart defects. In the long-term course, cardiovascular problems such as cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure or pulmonary hypertension may occur despite successful correction. In approximately 10-15% of all pregnancies of women with AHF, cardiac complications occur, endangering both mother and child. Preconceptional counseling and risk assessment is necessary to ensure that women who wish to have children can make an informed decision to become pregnant or not. Specific knowledge of the cardiac defect and the anticipated effects of pregnancy is essential. Subsequent prenatal care requires close collaboration between obstetricians and cardiologists. Depending on the complexity of the heart defect and the surgeries performed, care at a tertiary center may be necessary. In the vast majority of cases, vaginal delivery is the recommended mode of delivery from a cardiac perspective. Complications may not occur until the postpartum period. Depending on the heart defect, early discharge after birth may not be appropriate.

Congenital heart defects (AHF) are the most common birth defects and are found in 0.8% of all live births. Thanks to medical advances in recent decades, more than 90% of children with AHF now reach adulthood. Despite this development, corrected heart defects are generally not the same as “cured” heart defects. In the long-term course, various cardiovascular problems such as cardiac arrhythmias, valvular or conduit degeneration, heart failure, or pulmonary hypertension may occur. Mothers with AHF represent the largest group of pregnant women with heart disease in Western countries. In the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Pregnancy Registry, two-thirds of >1300 included mothers have AHF, 25% have degenerative valve disease (e.g., after rheumatic fever), 7% have cardiomyopathy, and 2% have coronary cardiopathy [1]. Because of the potential for long-term complications despite heart defect correction, women with AHF have an eightfold increased risk of cardiovascular events, defined as death, decompensated heart failure, arrhythmias requiring treatment, cerebrovascular event, or systemic embolism. Deaths occur in 150 of 100,000 pregnancies with AHF vs. 8 of 100,000 pregnancies without heart defects [2].

Pregnancy places a hemodynamic burden on all women. By the end of the second/beginning of the third trimester, peripheral resistance decreases by 40-70%, blood volume increases by 30-50%, heart rate increases by 10-20 beats per minute, and cardiac output increases by 30-50%. Pregnancy, simply put, is a “high output, low resistance” situation with an additional prothrombotic tendency [3]. Depending on the contractile reserve of the systemic ventricle, postoperative hemodynamics, extent of existing arrhythmogenic substrates, or residual shunts, the risk of pregnancy-related complications increases. Women with AHF and a desire to have children who have avoided regular care since childhood for various reasons are not infrequently referred for cardiac evaluation by their primary care physician or gynecologist in anticipation of pregnancy. Here, a comprehensive site assessment is even more important, as they may have hemodynamic findings that require intervention before possible pregnancy [4]. Depending on the complexity of the heart defect, referral to a specialized center may be necessary. Specialized centers in Switzerland are listed at www.sgk-watch.ch.

Preconceptual consulting

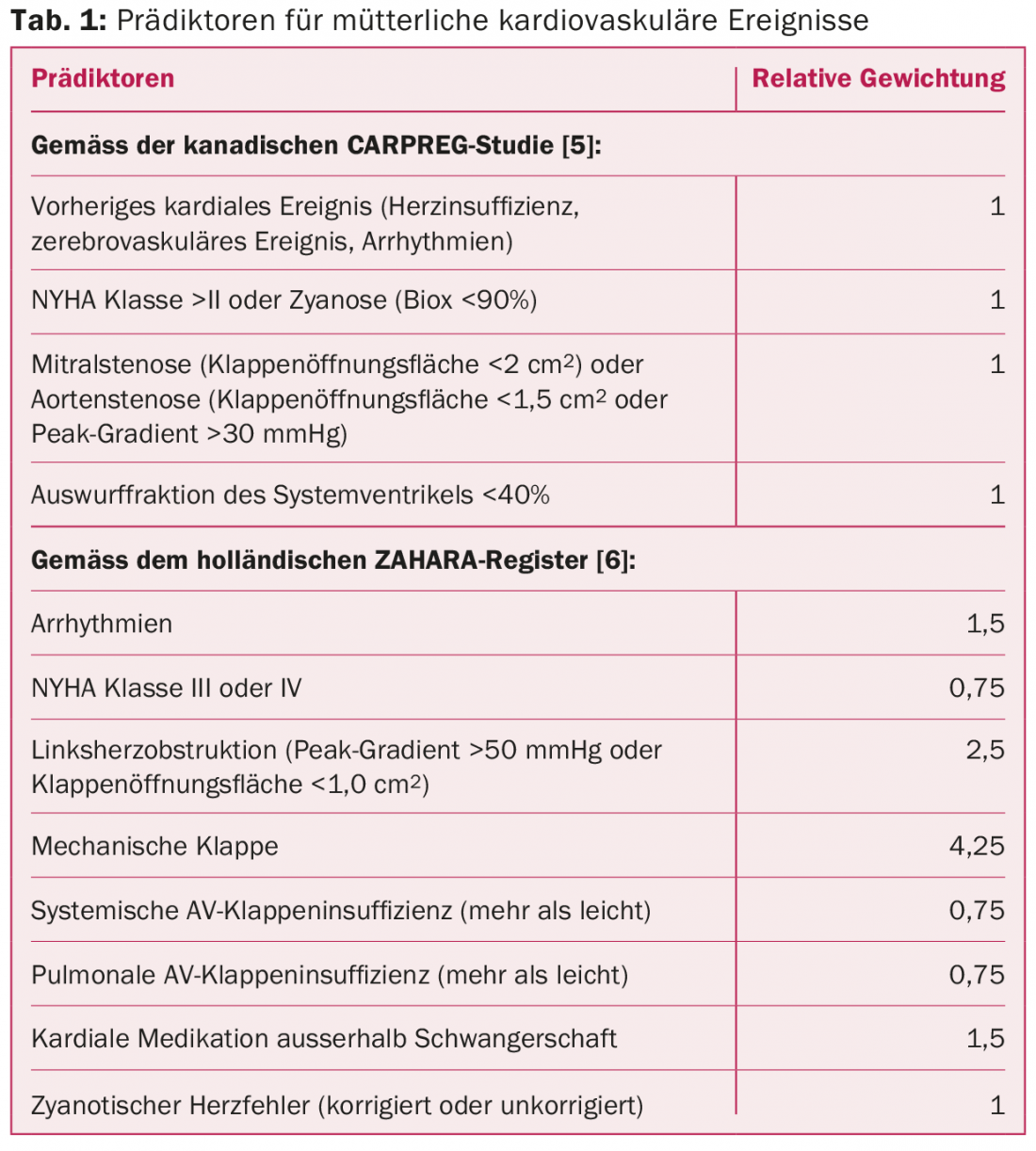

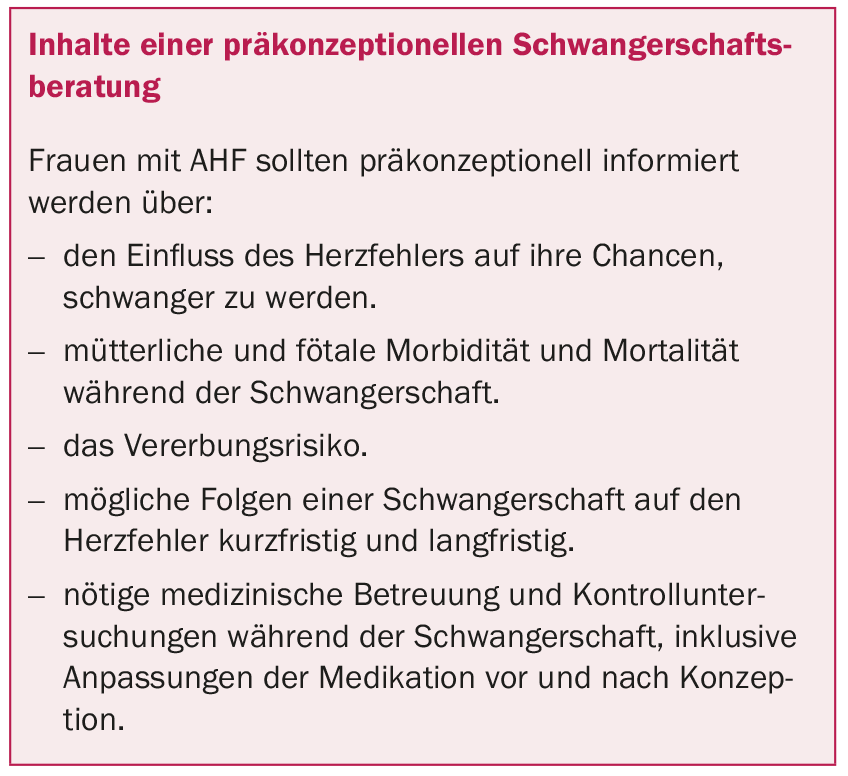

Discussions about family planning and contraception should begin in adolescence to prevent unplanned or very high-risk pregnancies if possible. In this consultation, among other things, the pregnancy risk for mother and child is assessed. The aim is to enable AHF patients to make an informed decision about whether or not to take the risks of pregnancy (Tab. 1) . Depending on the heart defect and family history, this risk assessment may include a recommendation for genetic testing.

Maternal risk assessment

In prospective studies, cardiac complications occurred in women with AHF in an average of 10-15% of all pregnancies [5,6]. These include arrhythmias, decompensated heart failure, cerebrovascular insults, embolic events, endocarditis, myocardial infarction, and, in the worst cases, cardiac death. The complication rate depends on the complexity of the heart defect. The patient’s individual performance before pregnancy suggests her functional reserve and estimates how hemodynamic adjustments will be tolerated in the context of pregnancy. Different risk scores allow a rough estimation of the probability of complications, which is supplemented by cardiac defect-specific aspects in a second step. Table 1 lists various predictors of cardiac complications during pregnancy.

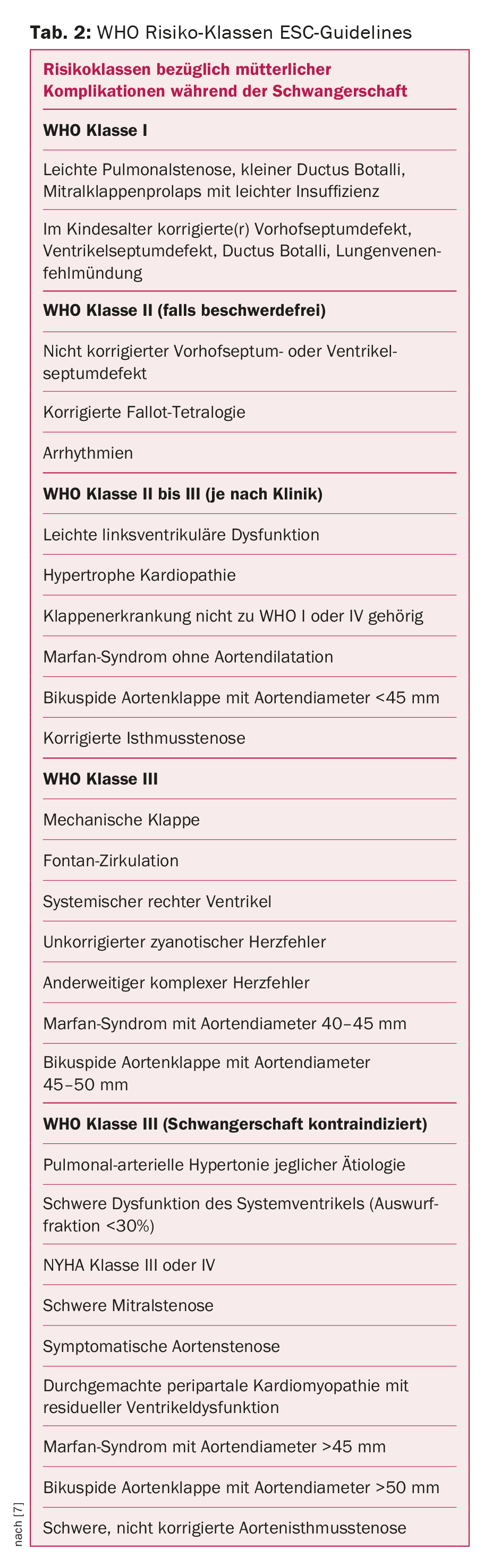

A simple and well-validated risk assessment is also provided by the European Guidelines on Cardiac Disease and Pregnancy [7]. Four risk classes are distinguished here (Tab. 2).

Increased mortality is not expected in the lowest risk class WHO I, which is considered small. In the highest risk class IV, pregnancy must be strongly discouraged. In WHO Class II, the risk of complications is considered moderate, and in WHO Class III, the risk is considered high. It is recommended that WHO class I risk women be cardiac evaluated once or twice during pregnancy, WHO class II women once per trimester, and WHO class III women monthly or every other month. Women in WHO risk classes II-III with additional unfavorable predictors or women in WHO classes III and IV should be affiliated with a tertiary center during pregnancy, where a team of obstetricians, specialized cardiologists with experience in the care of adults with AHF, anesthesiology, and neonatology are involved in the treatment plan.

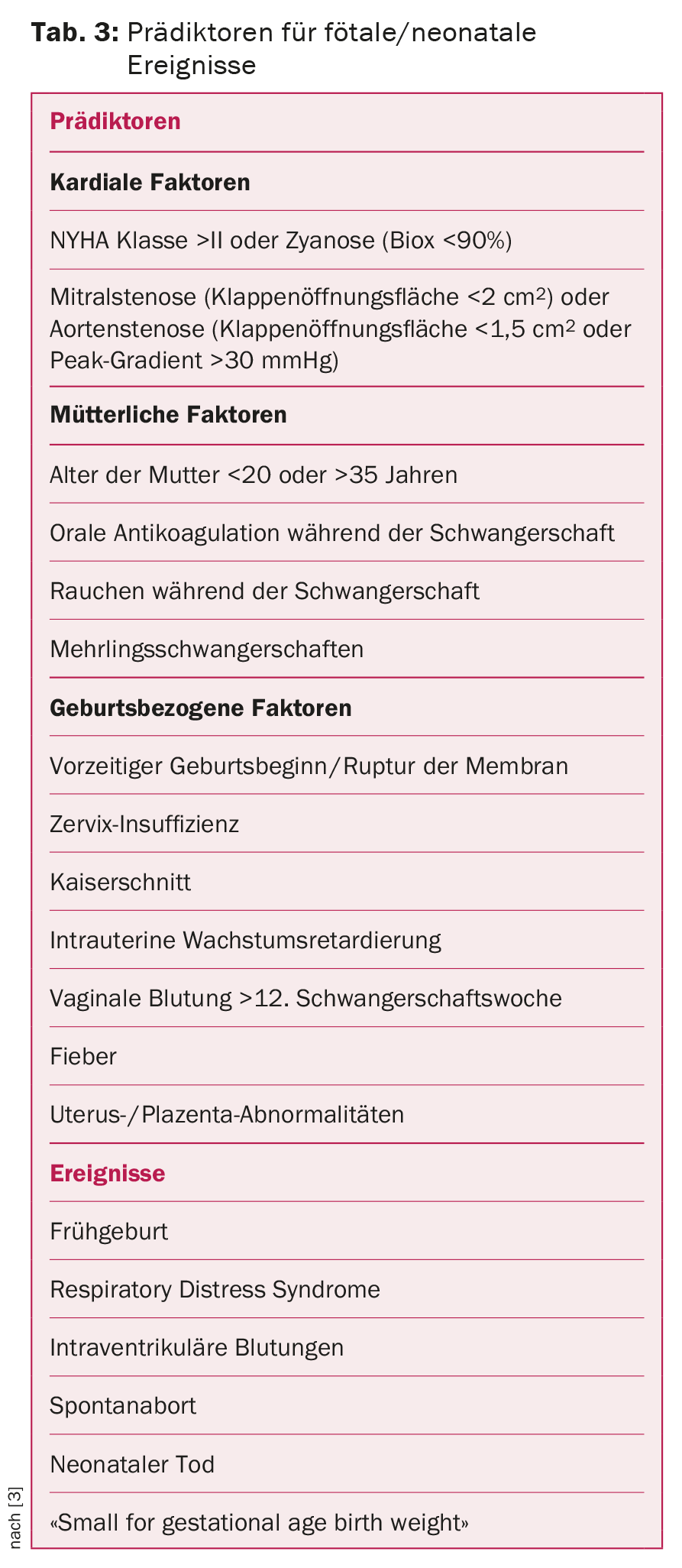

More difficult to assess than maternal risk is the likelihood of fetal and neonatal complications. Possible risk factors are listed in Table 3. Although these risk factors were significantly associated with an unfavorable outcome in the respective studies, subsequent prospective studies could only confirm their predictive value to a limited extent [8].

Inheritance risk

In parents with AHF, fetal echocardiography is performed at 18-22 weeks of gestation. Week of pregnancy recommended [7]. At this time, heart development is complete and major heart defects are evident. The risk that the fetus of a pregnant woman with AHF may itself have AHF is 3-12%, compared with the risk of 0.8% in the general population. Certain heart defects may additionally be associated with chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., tetralogy of Fallot with microdeletion 22q11). In these cases, the risk of inheritance is up to 50% and pre-conceptional genetic counseling and clarification should be discussed.

Cardiac drugs

Certain medications should be discontinued in a timely manner during pregnancy. These include, for example, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists, endothelin receptor antagonists, amiodarone, and statins. The ESC guidelines provide a helpful overview of the medications that can be used and those that should be avoided during pregnancy and lactation [7]. In patients with mechanical heart valves and the need for oral anticoagulation, the pendulum of recommendations is currently swinging toward continuation of vitamin K antagonist therapy during pregnancy. Recently, the American guidelines also advise against using unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin as the sole anticoagulant throughout pregnancy [9]. Bridging oral anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists with low-molecular-weight heparin during the sixth to twelfth week of pregnancy has been proposed as a solution, because the risk of Marcoumar-induced fetopathy is highest during this period. When using low-molecular-weight heparin during pregnancy, it should be noted that purely weight-adjusted drug dosing is inadequate and twelve-hourly dosing is necessary. It is recommended that Factor Xa activity (target range 0.8-1.2 U/ml, 4-6 hr after administration) be determined at least biweekly.

Heart failure

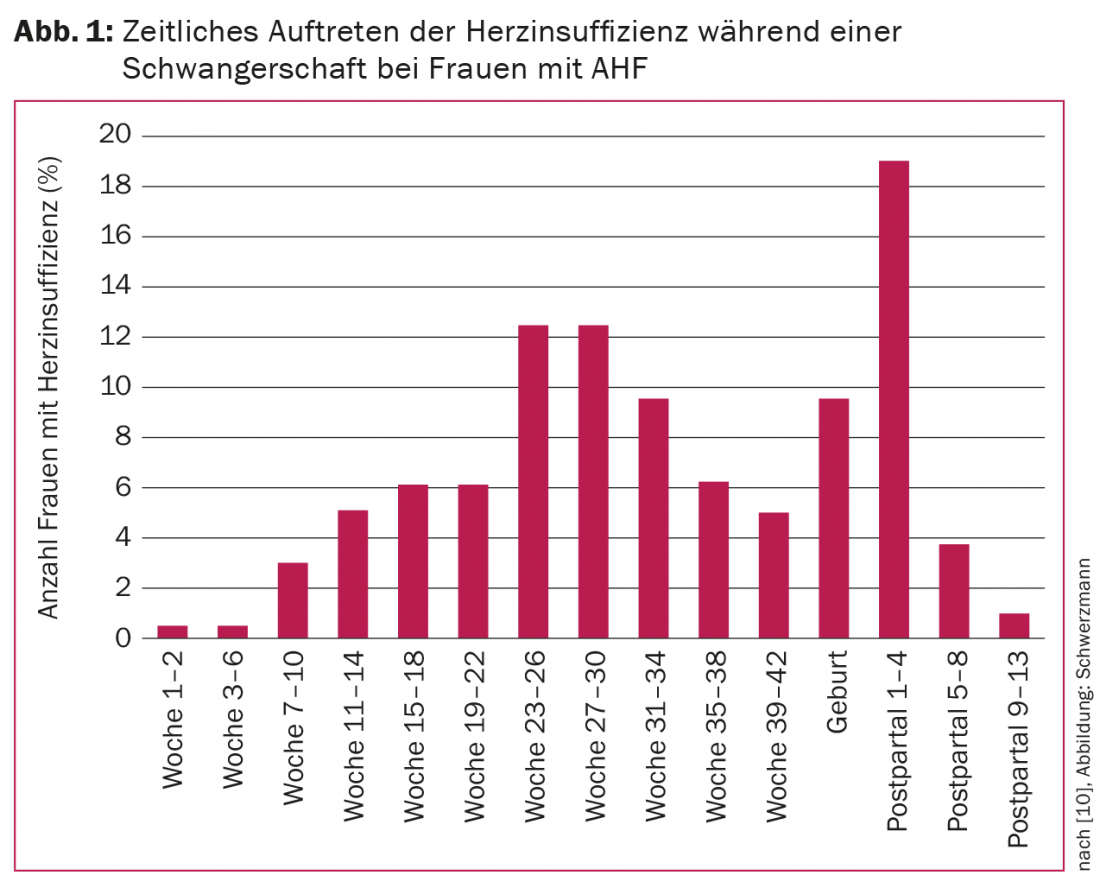

Progressive heart failure is one of the most common complications during pregnancy with AHF. In left ventricular obstruction, heart failure often occurs at the end of the second trimester; in preexisting cardiomyopathy (systemic right ventricle, hypertrophic cardiopathy, tetralogy of Fallot, cardiomyopathy), it occurs more frequently peri- and early postpartum. Figure 1 shows the temporal occurrence of heart failure in the 173 of >1300 women in the ESC registry who had cardiac decompensation during follow-up. Mothers with WHO risk class III or IV heart defects, pre-existing history of heart failure (strongest risk factor), known cardiomyopathy, pulmonary hypertension, or preconceptional NYHA class III or IV are at particular risk. Depending on the risk, the probability of heart failure is 4-68%. Maternal and fetal mortality are 5% each in pregnant women with heart failure compared with 0.5% and 1.2% without heart failure [10].

Care during pregnancy, birth and the postpartum period

Cardiac monitoring during pregnancy has the purpose of documenting pregnancy-induced hemodynamic changes and, depending on the course, adjusting recommendations regarding the mode of delivery. Depending on the situation, additional changes in medication must be ensured. For example, the pharmacokinetics of metoprolol change during pregnancy, necessitating successive dose increases to achieve stable beta blockade.

From a cardiac point of view, vaginal delivery is preferred in most patients because the risk of bleeding, infection, and thromboembolism is lower than with cesarean section [7]. In addition, changes in volume status are usually less abrupt and pronounced with vaginal delivery. Sectio is recommended in the following situations:

- Marfan patients with aortic diameter

- >45 mm or with progressive aortic dilatation during pregnancy.

- Acute or chronic aortic dissection

- Decompensated heart failure

- Severe aortic stenosis

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Oral anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists within the last two weeks before birth.

Early epidural analgesia is an important component in reducing pain-related catecholamine output and its effects on arrhythmic risk and circulation. Circulatory monitoring of the mother during delivery is based on baseline hemodynamic status. Continuous ECG lead is recommended for increased arrhythmia risk, and continuous Biox measurement is also recommended for patients with situational cyanosis. Current endocarditis guidelines do not suggest routine antibiotic shielding for either vaginal delivery or cesarean section, even in the presence of high-risk situations such as artificial heart valves [11].

Childbirth is associated with marked intravascular volume shifts, and in the first few days postpartum, as mentioned, there is also an increased risk of heart failure. Careful circulatory monitoring in these cases should include the first days after birth. About four to six months after birth, a new cardiological assessment is necessary to document any unfavorable long-term effect of the pregnancy on the heart defect. This time is also needed because by then the pregnancy-induced effects on hemodynamics will have completely reverted.

Literature:

- Roos-Hesselink JW, et al: Outcome of pregnancy in patients with structural or ischaemic heart disease: results of a registry of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013; 34(9): 657-665.

- Opotowsky AR, et al: Maternal cardiovascular events during childbirth among women with congenital heart disease. Heart 2012; 98(2): 145-151.

- Wald RM, Sermer M, Colman JM: Pregnancy and contraception in young women with congenital heart disease: general considerations. Paediatr Child Health 2011; 16(4): e25-29.

- Yeung E, et al: Lapse of care as a predictor for morbidity in adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol 2008; 125(1): 62-65.

- Siu SC, et al: Prospective multicenter study of pregnancy outcomes in women with heart disease. Circulation 2001; 104(5): 515-521.

- Drenthen W, et al: Predictors of pregnancy complications in women with congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J 2010; 31(17): 2124-2132.

- ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011; 32(24): 3147-3197.

- Balci A, et al: Prospective validation and assessment of cardiovascular and offspring risk models for pregnant women with congenital heart disease. Heart 2014; 100(17): 1373-1381.

- Nishimura RA, Warnes CA: Anticoagulation during pregnancy in women with prosthetic valves: evidence, guidelines and unanswered questions. Heart 2015; 101(6): 430-435.

- Ruys TP, et al: Heart failure in pregnant women with cardiac disease: data from the ROPAC. Heart 2014; 100(3): 231-238.

- Habib G, et al: Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): the Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and the International Society of Chemotherapy (ISC) for Infection and Cancer. Eur Heart J 2009; 30(19): 2369-2413.

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(3): 4-8