Respiratory distress triggers a very high level of suffering – both for those affected and for their relatives and professional environment. Respiratory distress is a common phenomenon and affects over 50% of patients at the end of life. Data even suggest an increase in symptom burden from respiratory distress to death. COVID-19 disease can also cause hypoxia and tachypnea on the one hand, and a high symptom burden with dyspnea and anxiety on the other, especially in unstable or dying patients.

Respiratory distress triggers a very high level of suffering – both for those affected [1] and their relatives [2] as well as the professional environment. Respiratory distress is a common phenomenon and affects over 50% of patients at the end of life [3]. Data even suggest an increase in symptom burden from respiratory distress to death [1]. The currently emerging COVID-19 disease can also cause hypoxia and tachypnea on the one hand, and high symptom burden with dyspnea and anxiety on the other hand, especially in unstable or dying patients [4].

Respiratory distress and changes in breathing can occur in the course of a wide variety of chronic and progressive diseases, especially in the fields of oncology, neurology, pneumology, or cardiology [5]. This often leads to emergency consultations and hospitalizations in the last months and weeks of life of the affected individuals [6]. The terms shortness of breath or dyspnea refer to a subjective perception of the affected person. Thus, respiratory distress is also described by patient narratives as air hunger, shortness of breath, breathlessness, breath pinching, labored breathing, and in extreme cases, a feeling of suffocation. Thus, respiratory distress cannot be measured, but must be inquired about.

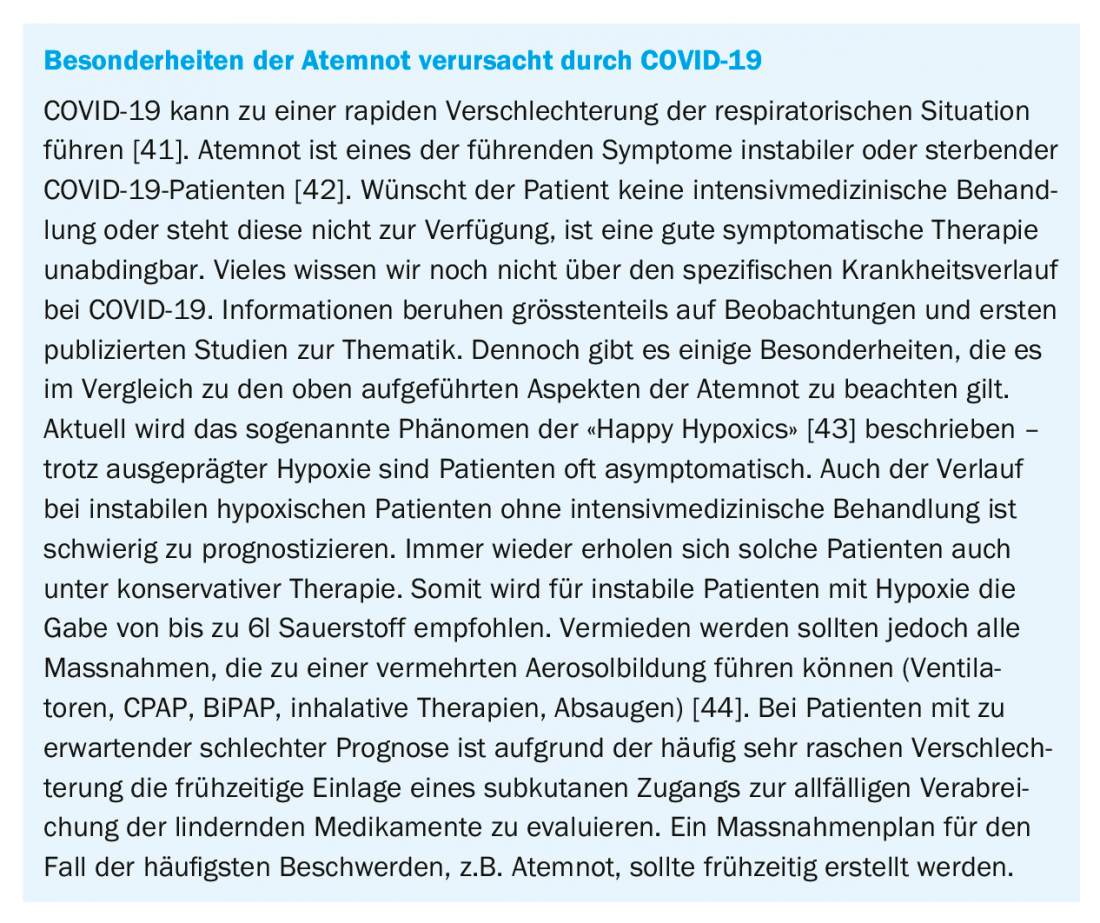

In contrast, the terms respiratory insufficiency or respiratory insufficiency stand for objectively observable changes in external mechanical respiration or pulmonary gas exchange, respectively. The subjective and objective changes may occur simultaneously, but they may also occur independently and need not correlate [7,8]. This phenomenon was also recently observed with COVID-19 [9]. This means, for example, that a patient may experience no dyspnea despite an oxygen saturation of only 70% and tachypnea, but in the same way a patient with an oxygen saturation of 95% may experience the most severe dyspnea. Not only, but especially in the last phase of life and in the dying process, the recognition and differentiation of these phenomena by the treating physicians is fundamental in order to be able to alleviate suffering in an adequate way and to accompany the affected persons well [10]. The following section discusses the topic of respiratory distress, its possible causes, and end-of-life therapies.

Definition and etiology

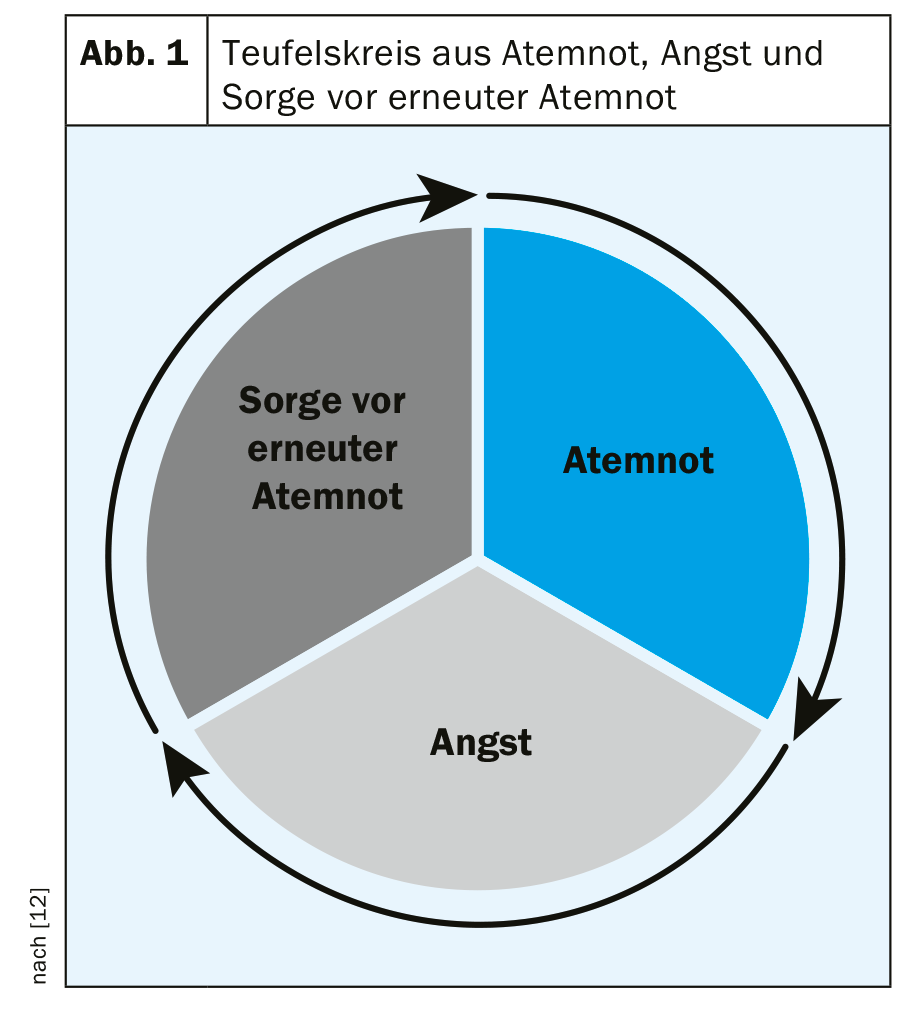

The American Thoracic Society (ATS) defines dyspnea as a subjective perception of respiratory distress that consists of qualitatively different sensations and can vary in intensity. Perception arises from the interaction between multiple physical, psychological, social, and environmental factors and may condition secondary physiological and behavioral responses. However, it is explicitly emphasized in this context that only the affected person can feel and evaluate respiratory distress/dyspnea [11]. In the genesis and maintenance of respiratory distress, psychological factors are often not merely incidental influencing factors. Thus, fear also very often plays a relevant role [7], creating a spiral of mutual potentiation (Fig. 1) [12]. The strain on a physical and psychological level and the accompanying restrictions on social participation are grueling for those affected. The dyspnea may be continuous, but it may also occur intermittently in the form of attacks of dyspnea [13]. In some cases, triggers are delineable; in others, they are not.

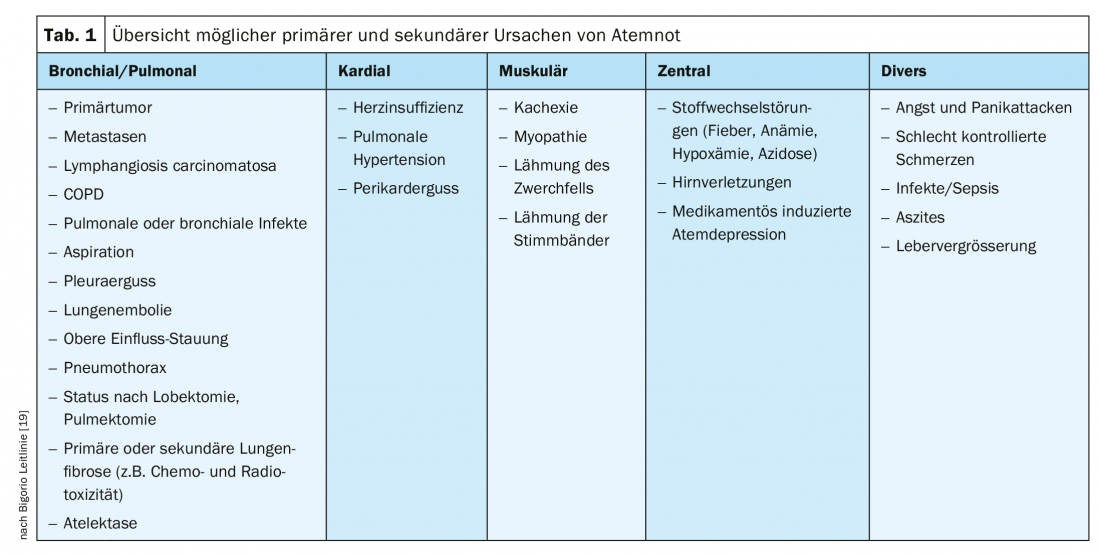

Respiratory distress is a common symptom of patients at the end of life, whether with tumor or non-tumor disease [15]. Thus, in the context of palliative care, malignant tumor diseases with pulmonary manifestations and their complications (pulmonary embolisms, pleural effusions, anemia, etc.), neuromuscular diseases (e.g., ALS), advanced heart failure, or COPD are particularly causative for changes in respiration and the occurrence of dyspnea [11]. Table 1 provides an overview of the possible pathologies that can lead to respiratory distress. The important thing here is to look for and treat reversible causes.

Assessment and diagnostics

Because of the subjectivity of dyspnea and the fact that physicians often underestimate symptom burden [16], a systematic and standardized recording of symptom burden is useful in principle. In principle, this is done by the assessment of the person concerned himself. A numerical classification e.g. according to the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) or the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) can be used and help to assess the progression in case of repeated application. In addition to the quantitative assessment of sensory symptom burden, the functional limitations experienced as a result of respiratory distress and emotional distress should also be recorded [17].

In the case of vigilance reduction, severe cognitive or physical limitations, such as those that occur during the dying phase, an external assessment may be necessary. One validated instrument is the Respiratory Distress Observation Scale (RDOS) [18]. This comprises various objectively ascertainable aspects, which in combination can provide a valid statement about the level of respiratory distress.

In palliative care contexts, evaluation of remediable causes of respiratory distress is also part of the process [17,19]. Reversible respiratory distress triggers may occur due to the common malignant and nonmalignant disease entities mentioned earlier. These can be, for example, pleural effusions in pulmonary tumor diseases or heart failure, increased abdominal volume due to ascites, a pneumothorax or pneumonia (see also table 1) . The initial diagnostic focus is on clinical examination and assessment. Further diagnostic means such as laboratory, X-ray, sonography, computed tomography or blood gas analysis may be useful. However, decisions about further investigations should always be based on the patient’s overall situation and prognosis, as well as the treatment goal jointly defined by the patient, the relatives, and the treatment team. Not everything that is possible is sensible and purposeful. Often, relief from discomfort is much more important than stressful examinations.

Therapy

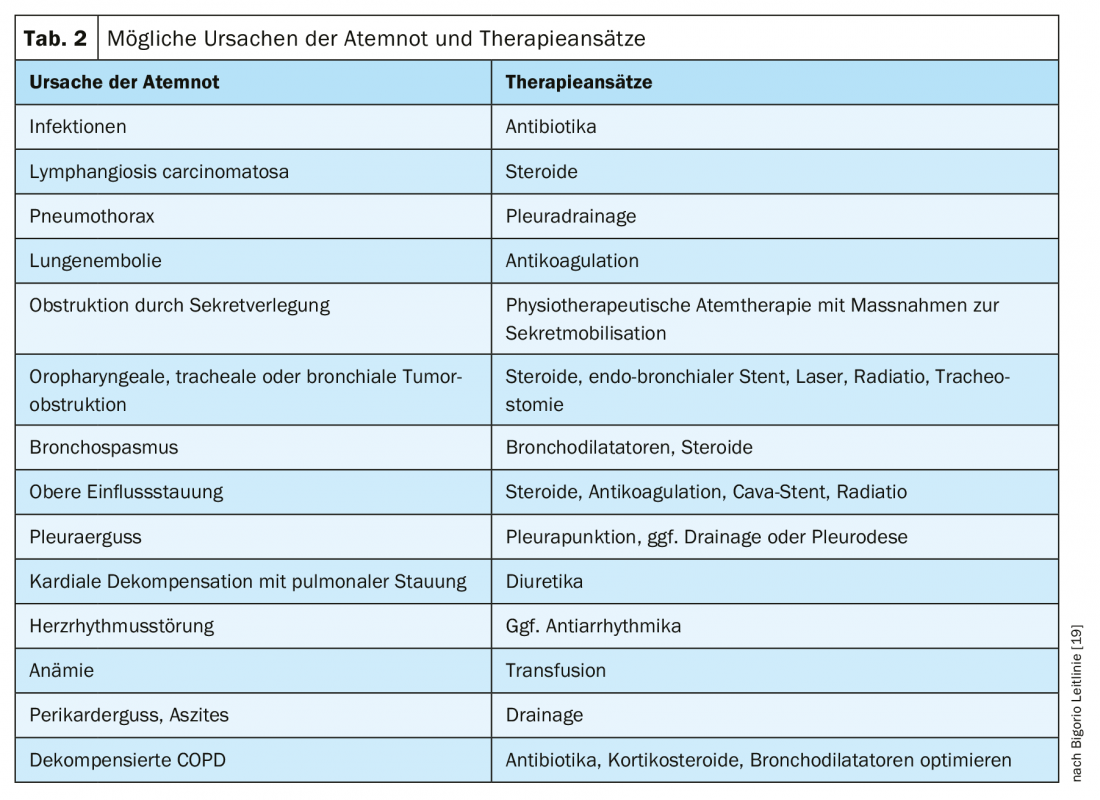

If potentially remediable causes of dyspnea are present, an attempt should be made to treat them – but here, too, according to the paradigm “not everything that is possible is useful.” Table 2 lists treatable causes of dyspnea and their specific treatment options for each. These interventions are particularly relevant in the palliative and end-of-life care phases. In the terminal phase, these take a back seat; the burden here would be greater than the benefit. It is always important to explicitly evaluate the benefits of the specific measure. Whether the intervention (e.g., transfusion, pleural puncture) reduced respiratory distress and, if so, to what extent? The evaluation forms the basis for decisions on the continuation or repetition of the intervention.

Symptomatic therapy is carried out in parallel with any treatment of reversible causes. The use of non-drug and drug measures is recommended [19]. Nonpharmacologic interventions [20] include walking aids [20], relaxation exercises [21], breathing training [21], and the use of ventilators to create airflow in the facial area [22]. During attacks or exacerbations of dyspnea, a quiet environment, a person present, a comfortable sitting position, and cooling drafts on the face (from a fan, open window) are helpful. The education of those affected and their relatives is also an important aspect. Eduction can also include guidance on self-help in the form of an emergency plan on which specific non-drug and drug instructions for action are listed, e.g. in the event of a respiratory distress attack. It is important that the plan and the measures are concretely discussed in advance and practiced with the patient as well as the relatives. Through the contingency plan, the patient and family members are empowered to act on their own, thus increasing their autonomy [23].

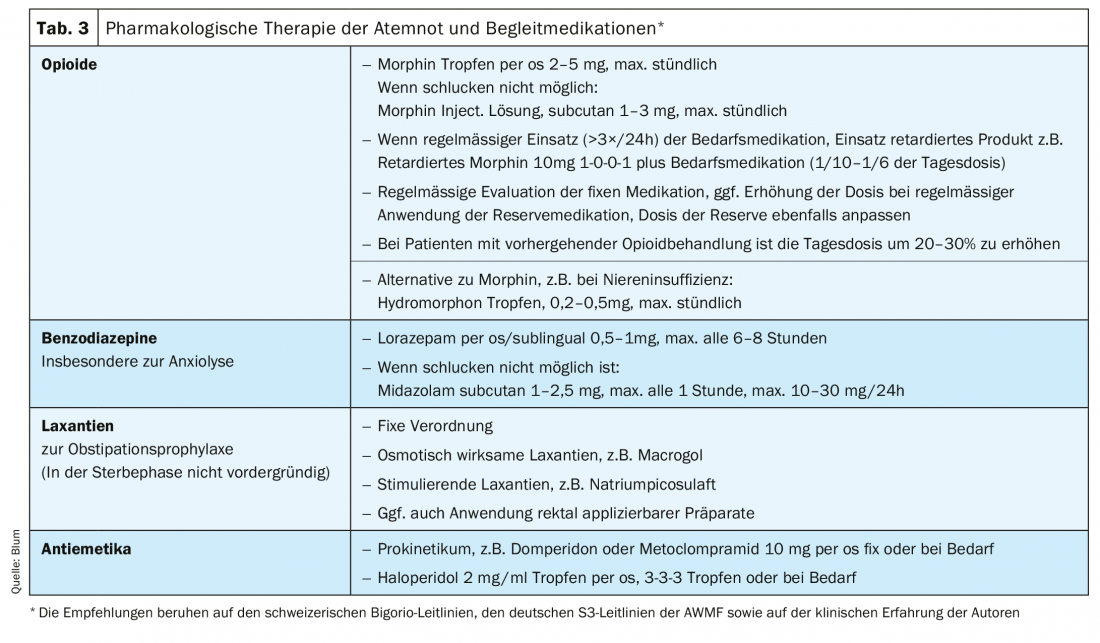

For pharmacological symptomatic therapy, the use of opioids is primarily recommended [17,19]. The study record for the efficacy of morphine in the treatment of refractory dyspnea is the best compared with other opioids, although again there are no homogeneous results [24–27]. Results regarding the efficacy of agents such as fentanyl, hydromorphone, and oxycodone are also heterogeneous and less conclusive [27–30]. No data are available regarding the efficacy of buprenorphine for the treatment of dyspnea. Nevertheless, other opioids e.g. in case of contraindication of morphine (renal insufficiency [31], intolerances) are among the alternatives used in clinical practice. In addition to the oral form of administration, parenteral (subcutaneous or intravenous) routes of administration are also available. No data showing efficacy can be found for either nasal/inhalation or transdermal use [27]. In vigilant patients who can swallow, the oral dosage form is preferred. If respiratory distress attacks are difficult to break through, and in the dying phase, parenteral use is usually switched to. In the case of patients with dysphagia, the transdermal route of administration of fentanyl may be considered despite a lack of evidence in the absence of proportionate alternatives.

The initial use of low-dose short-acting preparations (e.g., morphine drops) is recommended. With regular use, the prescription of sustained-release preparations combined with short-acting preparations is useful when needed. Preventive use of short-acting preparations before stress is also recommended to avoid the occurrence of respiratory distress attacks. In principle, the dosage depends on the clinic and intensity of respiratory distress. Compatibility also plays a relevant role. Nausea and fatigue may occur, especially at the beginning of opioid therapy [27], but these usually subside after a few days. Prophylactic antiemetic therapy with a prokinetic or haloperidol may be considered. Not subject to the habituation effect is the occurrence of constipation, which must be treated consistently and preventively. In geriatric patients in particular, the use of opioids can trigger delirium [32], so cautious tapering is advisable here. The risk of respiratory depression or relevant respiratory complications, feared by many physicians, is practically non-existent when dosing according to the principles of titration and adjustment [33].

The mechanisms of action of opioid therapy for the treatment of respiratory distress include increasing cerebralCO2 tolerance, decreasing respiratory rate, increasing respiratory volume, improvingCO2 elimination, and decreasing work of breathing. Thus, in addition to dampening the emotional response in the limbic system, an improvement in breathing mechanics occurs.

Benzodiazepines are also used [34,35]. In particular, in situations where the reinforcing effect due to anxiety is relevant, the use of benzodiazepines is recommended [17,19]. In addition to midazolam, which can be administered parenterally (subcutaneously or intravenously) but also nasally, lorazepam (sublingual, oral) is frequently used. So benzodiazepines are used in addition to an opioid, not instead of it. Steroids may also be used when a single cause cannot be clearly delineated and a multifactorial event is suspected [36]. There is also recent data that mirtazapine may help with shortness of breath [37].

Studies show no significant relief of respiratory distress with the use of oxygen in patients near death [38,39]. However, if the use of oxygen brings a subjective benefit for the affected person in the individual case, the use in moderate amounts (1-2 l, max. 4 l) can still be useful [19]. In the dying person, however, the undesirable aspects predominate, such as the disturbing feeling in the face, drying of the mucous membranes and the emphasis on apparatus medicine.

In summary, an individually adapted therapy concept is necessary for the treatment of respiratory distress, which must be checked at short intervals for its effectiveness and side effects and regularly adjusted. The basis for the therapy concept are the pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy approaches listed above, which must and can be selected according to the individual patient situation. All of the drug therapy options listed here are off-label uses – a commonplace reality in palliative care [40].

Palliative sedation

In cases where no relevant reduction of suffering can be achieved despite the use of available drug and non-drug therapeutic measures and the suffering is no longer tolerable for the patient, sedation may be considered as an extreme option. In its 2019 guideline, the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS) formulates the option for action in these situations as follows: “In situations in which a symptom is nevertheless refractory and persists in an intolerable manner for the patient, the treatment option is temporary or continuous palliative sedation, i.e., the controlled use of sedating medications to reduce symptom perception by decreasing or eliminating consciousness. Dosage and choice of medication are based on the treatment goal (e.g., freedom from symptoms, relief of the patient). The duration of sedation depends on the triggering situation” [45]. Importantly, continuous deep sedation should be used only when available therapeutic options have been exhausted and in patients in whom the dying process has already begun [45]. The goal of sedation is to reduce suffering, not to shorten life.

Should sedation be considered due to unmanageable respiratory distress at the end of life, several conditions must be checked for their presence. These affect both the patient, the relatives and the treatment team [48]. A clearly structured and prescribed procedure is also recommended to avoid errors and misuse in this sensitive area. If in doubt, low-threshold consultation with a specialized palliative care team or clinical ethics team should also be considered. The above measures strengthen reflection and ensure the quality of the decision.

Finally, it should be emphasized that dyspnea is a complex symptom in chronic progedial diseases and in terminal stages of disease. The patient is at the center of the issue and the level of suffering is high. The symptoms can only be evaluated by the patient in the true sense of the word. Therapeutic concepts are oriented towards the treatment of reversible causes as well as non-drug and drug symptomatic treatment approaches. Continuous deep sedation is a measure that should be used only in cases of failure of other therapeutic approaches, high levels of distress, and when the dying process has already begun. The realistic treatment goal, which is defined together with the patient, relatives and the treatment team, is decisive for all therapy decisions. Early discussions about patient preferences, ideas, and priorities help to plan ahead, promote patient autonomy, and provide us treating physicians with valuable information for good end-of-life care.

Take-Home Messages

- Respiratory distress is always subjective.

- Respiratory distress and objective changes in respiratory/pulmonary function may occur independently.

- Respiratory distress is a complex symptom that can be triggered by various biological, psychological, social, and spiritual factors.

- Therapy refers to potentially reversible causes and symptomatic therapy.

- Symptomatic therapy includes drug and non-drug measures.

- Therapy decisions are based on the jointly defined treatment goal.

Literature:

- Campbell ML, et al: Trajectory of Dyspnea and Respiratory Distress among Patients in the Last Month of Life. J Palliat. Med 2018; 21: 194-199.

- Malik FA, et al: Living with breathlessness: a survey of caregivers of breathless patients with lung cancer or heart failure. Palliat. Med 2013; 27: 647-656).

- Simon ST, et al: Characteristics of patients with breathlessness – results of the German hospice and palliative care evaluation. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr 2016; 141: e87-95.

- Zhu J, et al: Clinical characteristics of 3,062 COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. J Med Virol 2020; doi: 10.1002/jmv.25884.

- Palmieri L: Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 patients dying in Italy Report based on available data on April 16th, 2020.

- Barbera L, et al: Why do patients with cancer visit the emergency department near the end of life? CMAJ Can. Med. assoc. j 2010; 182: 563-568.

- Bruera E, et al: The frequency and correlates of dyspnea in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2000; 19: 357-362.

- Hui D, et al: Dyspnea in hospitalized advanced cancer patients: subjective and physiologic correlates. J Palliat. Med 2013; 16: 274-280.

- Bertran Recasens B, et al: Lack of dyspnea in Covid-19 patients; another neurological conundrum? Eur. J. Neurol 2020; doi: 10.1111/ene.14265.

- Mitchell GK, et al: Systematic review of general practice end-of-life symptom control. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2018; 8: 411-420.

- Parshall MB, et al: An Official American Thoracic Society Statement: Update on the Mechanisms, Assessment, and Management of Dyspnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 2012; 185: 435-452.

- Sigurgeirsdottir J, et al: COPD patients’ experiences, self-reported needs, and needs-driven strategies to cope with self-management. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis 2019; 14: 1033-1043.

- Simon ST, et al: Episodes of breathlessness: types and patterns – a qualitative study exploring experiences of patients with advanced diseases. Palliat. Med 2013; 27: 524-532.

- Weingärtner V, et al: Characteristics of episodic breathlessness as reported by patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer: Results of a descriptive cohort study. Palliat. Med 2015; 29: 420-428.

- Moens K, et al: Are There Differences in the Prevalence of Palliative Care-Related Problems in People Living With Advanced Cancer and Eight Non-Cancer Conditions? A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 48: 660-677.

- Oechsle K, et al: Symptom burden in palliative care patients: perspectives of patients, their family caregivers, and their attending physicians. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2013; 21: 1955-1962.

- Guidelines Program Oncology (German Cancer Society, German Cancer Aid, AWMF): Palliative Care for Patients with Noncurable Cancer, Long Version 2.1. (2020).

- Campbell ML, et al: A Respiratory Distress Observation Scale for patients unable to self-report dyspnea. J Palliat. Med 2010; 13: 285-290.

- palliative.ch Dyspnea – Consensus on best practice in Palliative Care in Switzerland – expert group Swiss Society for Palliative Care 2003. (PDF)

- Bausewein C, et al: Non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness in advanced stages of malignant and non-malignant diseases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013.

- Bolzani A, et al: Cognitive-emotional interventions for breathlessness in adults with advanced diseases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012682.

- Kako J, et al: Immediate Effect of Fan Therapy in Terminal Cancer With Dyspnea at Rest: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2020; 37: 294-299.

- Skoch BM, Sinclair CT: Management of Urgent Medical Conditions at the End of Life. Med. Clin. North Am 2020; 104: 525-538.

- Abdallah SJ, et al: Effect of morphine on breathlessness and exercise endurance in advanced COPD: a randomised crossover trial. Eur. Respir. J 2017; 50.

- Mazzocato C, et al: The effects of morphine on dyspnea and ventilatory function in elderly patients with advanced cancer: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol 1999; 10: 1511-1514.

- Oxberry SG, et al: Short-term opioids for breathlessness in stable chronic heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2011; 13: 1006-1012.

- Barnes H, et al: Opioids for the palliation of refractory breathlessness in adults with advanced disease and terminal illness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2016; 3: CD011008.

- Ferreira DH, et al: Controlled-release oxycodone vs. placebo in the treatment of chronic breathlessness-A multisite randomized placebo controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 59: 581-589.

- Simon ST, et al: EffenDys-Fentanyl Buccal Tablet for the Relief of Episodic Breathlessness in Patients With Advanced Cancer: A Multicenter, Open-Label, Randomized, Morphine-Controlled, Crossover, Phase II Trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016; 52: 617-625.

- Simon ST, et al: Fentanyl for the relief of refractory breathlessness: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 46: 874-886.

- King S, et al: A systematic review of the use of opioid medication for those with moderate to severe cancer pain and renal impairment: a European Palliative Care Research Collaborative opioid guidelines project. Palliat. Med 2011; 25: 525-552.

- Swart LM, et al: The Comparative Risk of Delirium with Different Opioids: A Systematic Review. Drugs Aging 2017; 34: 437-443.

- Verberkt CA, et al: Respiratory adverse effects of opioids for breathlessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J 2017; 50.

- Simon ST, et al: Benzodiazepines for the relief of breathlessness in advanced malignant and non-malignant diseases in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2016; 10: CD007354.

- Navigante AH, et al: Morphine versus midazolam as upfront therapy to control dyspnea perception in cancer patients while its underlying cause is sought or treated. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010; 39: 820-830.

- Haywood A, et al: Systemic corticosteroids for the management of cancer-related breathlessness (dyspnoea) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2019; 2: CD012704.

- Lovell N, et al: Use of mirtazapine in patients with chronic breathlessness: A case series. Palliat. Med 2018; 32: 1518-1521.

- Campbell ML, et al: Oxygen is nonbeneficial for most patients who are near death. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 45: 517-523.

- Baldwin J, Cox J: Treating Dyspnea: Is Oxygen Therapy the Best Option for All Patients? Med. Clin. North Am 2016; 100: 1123-1130.

- Kwon JH, et al: Off-label Medication Use in the Inpatient Palliative Care Unit. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 54: 46-54.

- Fusi-Schmidhauser T, et al: Conservative management of Covid-19 patients – emergency palliative care in action. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.030.

- Lovell N, et al: Characteristics, symptom management and outcomes of 101 patients with COVID-19 referred for hospital palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.015.

- Couzin-Frankel J. The mystery of the pandemic’s ‘happy hypoxia’. Science 2020; 368: 455-456.

- Hendin A et al: End-of-life care in the emergency department for the patient imminently dying of a highly transmissible acute respiratory infection (such as COVID-19). CJEM 2020; 1-4 doi: 10.1017/cem.2020.352.

- Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences. Dealing with dying and death 2019.

- Ziegler S, et al: A. Continuous Deep Sedation Until Death-a Swiss Death Certificate Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med 2018; 33: 1052-1059.

- Twycross R. Reflections on palliative sedation. Palliat. Care 2019: 12.

- Mazzocato C: Palliative info – use of palliative sedation: clinical and ethical dimensions 2016.

- Campbell ML, Yarandi HN. Death rattle is not associated with patient respiratory distress: is pharmacologic treatment indicated? J. Palliat. Med 2013; 16: 1255-1259.

- Wildiers H, Menten J: Death rattle: prevalence, prevention and treatment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002; 23: 310-317.

- Mercadante S, et al: Hyoscine butylbromide for the management of death rattle: Sooner Rather Than Later. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 56: 902-907.

InFo PAIN & GERIATURE 2020; 2(1): 12-17.