Restless legs syndrome is a common and usually chronic condition whose treatment needs to be adjusted repeatedly during its course. In recent years, studies and recommendations on long-term therapy have become available that pay increased attention to “augmentation,” a paradoxical side effect of dopamine agonists, and therefore place greater emphasis on α2δ-ligands and, to some extent, opiates.

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a common neurological disorder that affects up to 4% of the female population and 2% of the male population. Although the severity of the symptoms often varies from day to day and over longer periods of time, RLS is usually lifelong. While it remains controversial whether the sleep disturbance caused by RLS poses a risk for cardio- and cerebrovascular disease, the negative impact of severe RLS on the quality of life of the sufferer and family members is well established.

Diagnosis – think about mimics

After being little known for a long time, awareness of RLS has grown encouragingly in recent years, both among physicians and medical laypersons. In this context, there was also a warning about the risk of overdiagnosis, which can lead to unnecessary drug prescriptions and corresponding costs and side effects. The most recent classification of sleep-wake disorders (ICSD-3) addresses this issue by striving for greater diagnostic specificity. As in the past, the diagnosis of RLS is based on four mandatory clinical criteria:

- Urge to move the legs, often associated with unpleasant sensations

- Amplification at rest, i.e. in sitting and lying position

- Clear improvement during physical activity

- Intensification of the complaints in the evening or during the night.

In order to make the diagnosis of RLS, all four criteria must be fulfilled or – since the duration of the symptoms can extend to the whole day as the severity of the disease increases – have been fulfilled once in the course of the disease. As a fifth criterion, which was also mandatory, it was added that the quality of life must be limited by the extent of the complaints.

These diagnostic criteria are mandatory but not specific for RLS. “RLS mimics” such as arthropathies, leg edema, leg cramps, or a “positional discomfort” (only when sitting, not lying down, with relief by simply changing the position of the legs) are sometimes described by sufferers in terms similar to RLS, but can usually be well delineated by asking specific questions. In the differential diagnosis of (small fiber) polyneuropathy, it is important to remember that it increases the risk for RLS, and thus both causes of paraesthesia and urge to move the legs may exist in the same person. In unclear cases, supportive findings from additional examinations such as the detection of periodic leg movements during sleep (PLMS) and wakefulness (PLMW) often associated with RLS by means of polysomnography or – more cost-effective – by means of ambulatory foot actigraphy and, most importantly, the response of symptoms to low doses of dopaminergic drugs are helpful. The typically positive family history in idiopathic RLS is often unreliable and a difficulty falling asleep, although typical, is too nonspecific as a diagnostic criterion.

After syndromic RLS diagnosis, few laboratory tests are usually useful with regard to factors that may trigger or exacerbate RLS, for example, renal insufficiency or iron deficiency.

Who needs treatment?

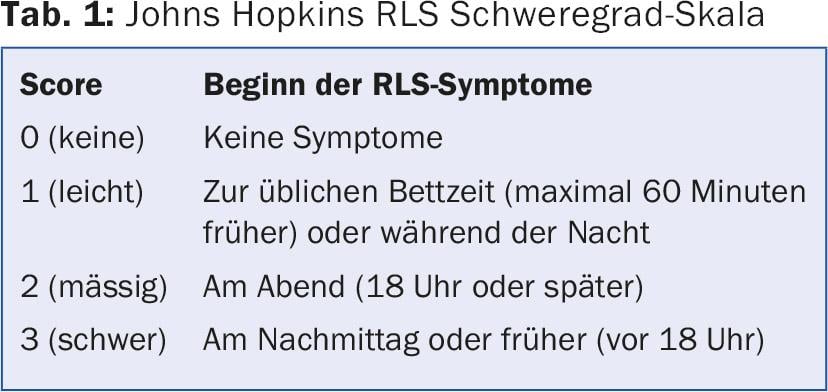

Not every person who meets the diagnostic criteria for RLS requires drug treatment. A degree of discomfort requiring treatment is usually assumed when the symptoms are present on at least two to three days per week and clearly impair the patient’s quality of life. Various scales are available to assess the severity of the disease, which allow the very important assessment of progression. For practical purposes, the Johns Hopkins Scale (Tab. 1) is well suited because it is also likely to detect augmentation at an early stage.

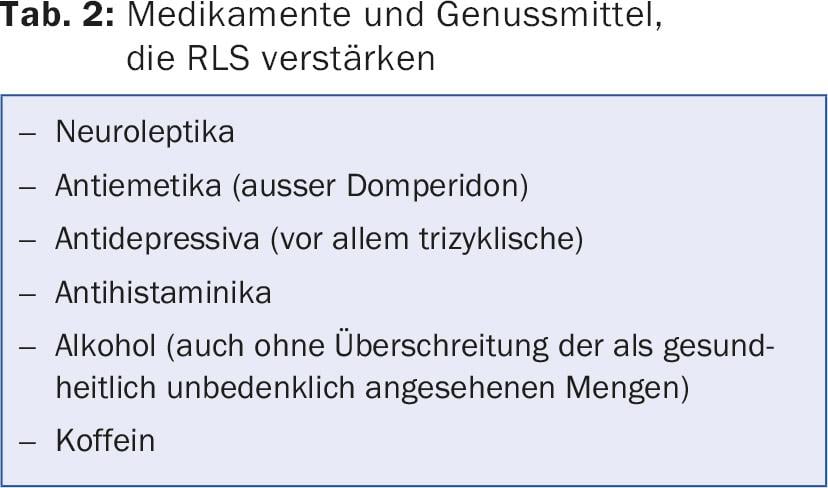

First, RLS-provoking stimulants as well as medications should be elicited and avoided if possible (tab. 2). Although antidepressants can exacerbate RLS in up to 10% of cases (especially mirtazapine [Remeron®]), approximately 70% of patients with comorbidity of RLS and depression benefit from them. Causal treatment is possible especially in secondary RLS as a result of iron deficiency. Although it has not yet been conclusively determined which patients with RLS benefit from iron supplementation, it is recommended at a ferritin <50-75 μg/l. If oral preparations result in an insufficient increase in ferritin or are poorly tolerated, intravenous administration of iron is an alternative.

Drug therapy of periodic leg movements during sleep (PLMS) without concomitant presence of RLS complaints during wakefulness under the concept of “periodic leg movement disorders” (PLMD) should only be performed with great caution, small drug doses and under close monitoring of subjective complaints such as fatigue, sleepiness or insomnia, so that augmentation is avoided in any case.

The choice of the first drug

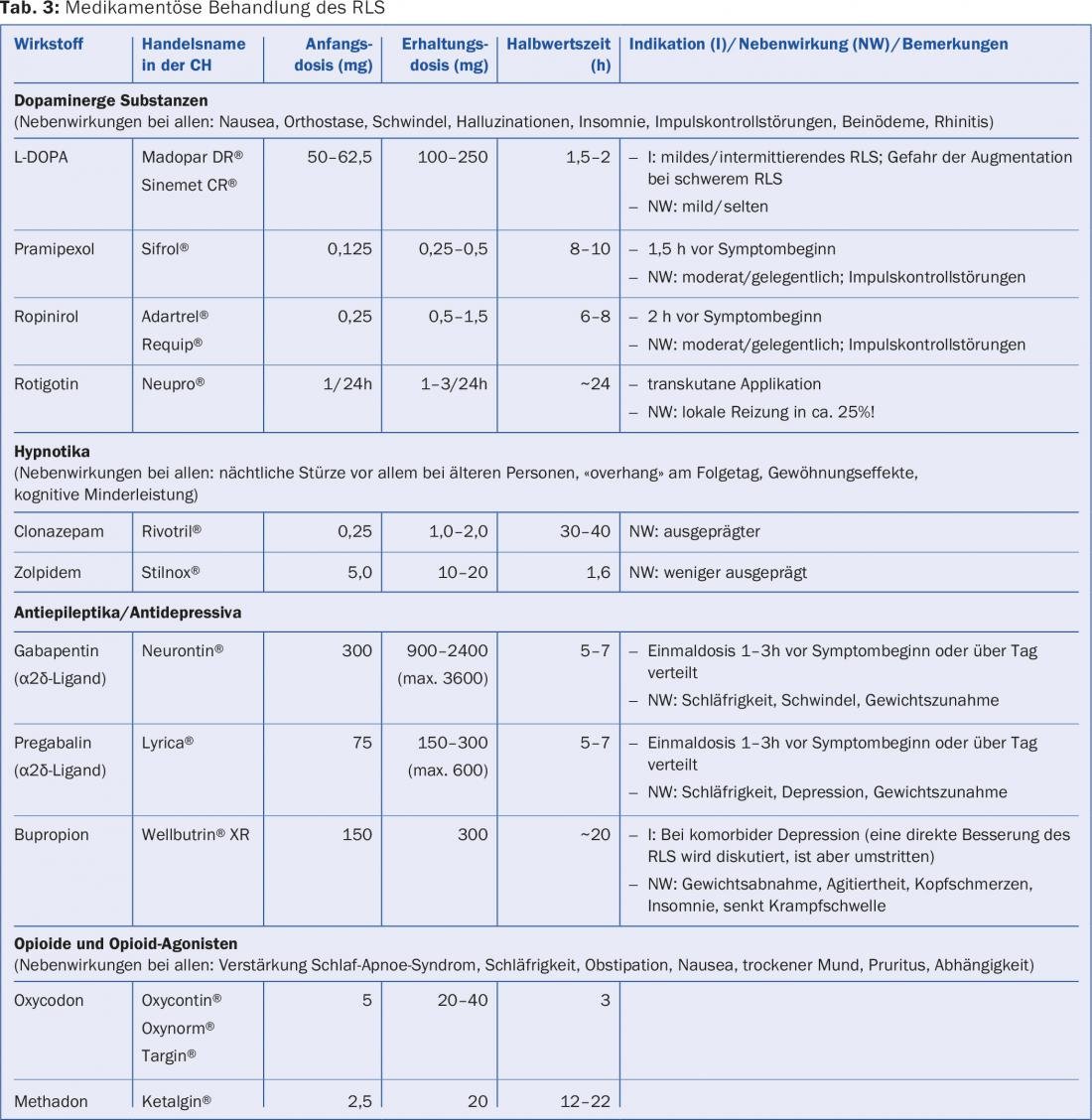

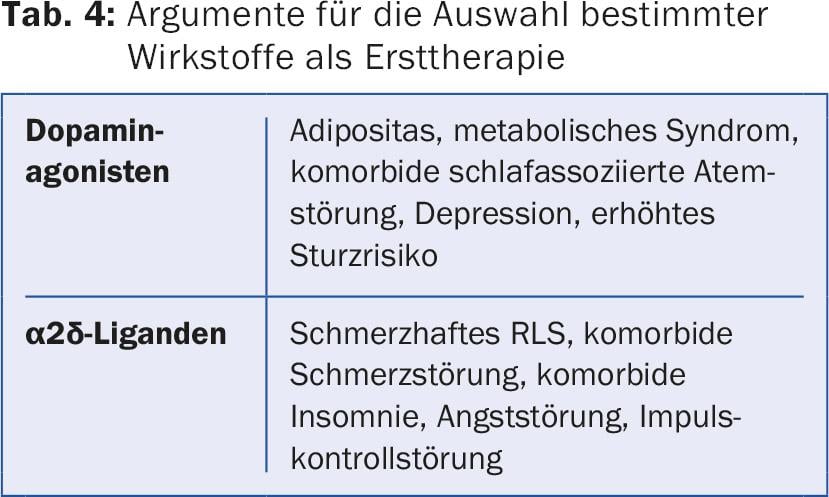

If no sufficient improvement can be achieved with the measures listed, various drug classes are available for the treatment of RLS (tab. 3) . The choice of drug depends on the severity and frequency of the symptoms, comorbidities and the potential side effects of the drugs (tab. 4).

Best known are probably the various dopamine agonists (DA) most commonly prescribed today, while L-DOPA may now rarely be recommended for very mild, intermittent RLS symptoms.

The short-term efficacy of DA has been demonstrated in several studies. These are usually a good choice, especially for patients who need a medication only occasionally – for example, when going to the theater in the evening. Then, for example, a short-acting DA (pramipexole, ropinirole) can be taken one to two hours before the expected symptoms.

Doubts about long-term success with dopaminergics have become increasingly topical because of the not-so-rare loss of efficacy and the most important and unfortunately relatively common side effect, augmentation. In addition to side effects that are usually easy to recognize, such as nausea, daytime sleepiness with the risk of microsleep, or even insomnia, patients should be made particularly aware of the often unrecognized impulse control disorders, such as uncontrolled eating, shopping, and gambling, as well as hypersexuality, before starting therapy and during follow-up examinations.

Recently, therefore, α2δ-ligands (pregabalin and gabapentin) have been recommended by some experts as alternative first-line drugs. Especially for patients with comorbid pain disorders, for example in the context of polyneuropathy, their primary use is definitely useful. Pregabalin may additionally be recommended for comorbid generalized anxiety disorder, which is common in RLS. These drugs are also associated with common but usually reversible side effects, such as drowsiness, dizziness, and weight gain. In a one-year comparative study with pregabalin and pramipexole, pregabalin was discontinued more frequently because of side effects, although efficacy was comparable.

In the natural course of RLS, there are also always spontaneous phases with minor symptoms, which is why established pharmacotherapy should be discontinued on a trial basis in a symptom-free or symptom-poor patient.

In the event of admission to a hospital or nursing home, we recommend that patients download the information sheet for hospital admission from the website www.restless-legs.ch and submit it to the relevant doctors and nursing staff.

When the treatment no longer works

If a patient with RLS experiences a recurrence of symptoms under previously effective drug treatment, the first step should be to look for behavioral changes and concomitant diseases that may exacerbate RLS. Decreased physical activity, increased alcohol consumption, or insomnia from other causes (e.g., lying down too long) can exacerbate RLS. Newly prescribed medications or discontinuation of an opiate medication taken for a long time are other causes of deterioration. As with the initial diagnosis, iron deficiency should again be sought.

In patients on dopaminergic medications, consider the possibility of augmentation, the annual incidence of which is around 10% in long-term treatment subjects. This is understood as the recurrence or rapid worsening of RLS symptoms under therapy within weeks, with symptoms appearing earlier and earlier in the day, after a shorter latency period at rest (after sitting down or lying down), and also involving previously unaffected body regions such as the arms. In addition to treatment duration, high dose and pharmacokinetic issues (more common with short-acting preparations, especially L-DOPA) and low ferritin are likely to favor the development of augmentation. Preventively, therefore, avoidance of high doses of dopaminergic drugs and, at most, the use of longer-acting galenic forms are reasonable.

If augmentation occurs under a short-acting DA, an initial attempt can be made to control symptoms occurring earlier in the day by spreading the total unchanged dose over several administrations (i.e., earlier in the day as well). Another option is to switch to a sustained-release form of pramipexole or ropinirole or to the DA rotigotine, which is applied transcutaneously and thus effective throughout the day; the latter occasionally causes cutaneous intolerance in addition to the usual DA side effects. Increasing the daily dose of DA may provide short-term relief of symptoms, but in the long term it increases augmentation, and this should also be pointed out to those affected.

If these measures do not lead to success, a switch to another substance class, primarily an α2δ-ligand, should be made. Because discontinuation of dopaminergic medication exacerbates RLS in the short term, the alternative drug should be dosed up to the recommended range before gradual reduction of DA.

Finally, as demonstrated in 2013 in a larger study with oxycodone/naloxone, opiates including methadone are an option for patients whose RLS cannot be adequately treated by DA and α2δ-ligands (alone or in combination). In addition to the risks of dependence and overdose, which are also relevant in the use of opiates for other indications, from the point of view of sleep medicine, particular attention should be drawn to the possible intensification of a sleep-associated respiratory disorder. Overall, long-term use of opioids for RLS should be discussed with a specialist.

Further difficult is the treatment of RLS in pregnancy, which unfortunately is often accompanied by an increase in symptoms. Both DA and α2δ-ligands should not be used during this period. The substitution of an iron deficiency is of particular importance here.

Although good long-term data are still scarce, most patients with RLS can be helped in the long term with the drugs available today. However, severe courses with resistance to therapy do occur. In addition to good cooperation between primary care providers and specialists, the support of self-help groups can then also be valuable for those affected (www.restless-legs.ch).

Further reading:

- Allen RP, et al: Comparison of pregabalin with pramipexole for restless legs syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(7): 621-631.

- Garcia-Borreguero D, et al: The long-term treatment of restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease: evidence-based guidelines and clinical consensus best practice guidance: a report from the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Sleep Med 2013; 14: 675-684.

- Sateia M: International Classification of Sleep Disorders. Third Edition. American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014. ISBN: 0991543416.

- Trenkwalder C, et al, RELOXYN Study Group: Prolonged release oxycodone-naloxone for treatment of severe restless legs syndrome after failure of previous treatment: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial with an open-label extension. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 1141-1150.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(1): 7-11