Psoriasis is a skin disease caused by a disorder of the immune system with subsequent strong cell growth. It can be divided into different forms: Plaque Psoriasis (Psoriasis vulgaris), Psoriasis guttata, Psoriasis inversa, Psoriasis pustulosa and Psoriasis erythrodermica. In most cases, sufferers only suffer from one type, although this can withdraw and, triggered by a trigger, recur in a different form. Advances in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris were discussed at the AAD Congress in Denver.

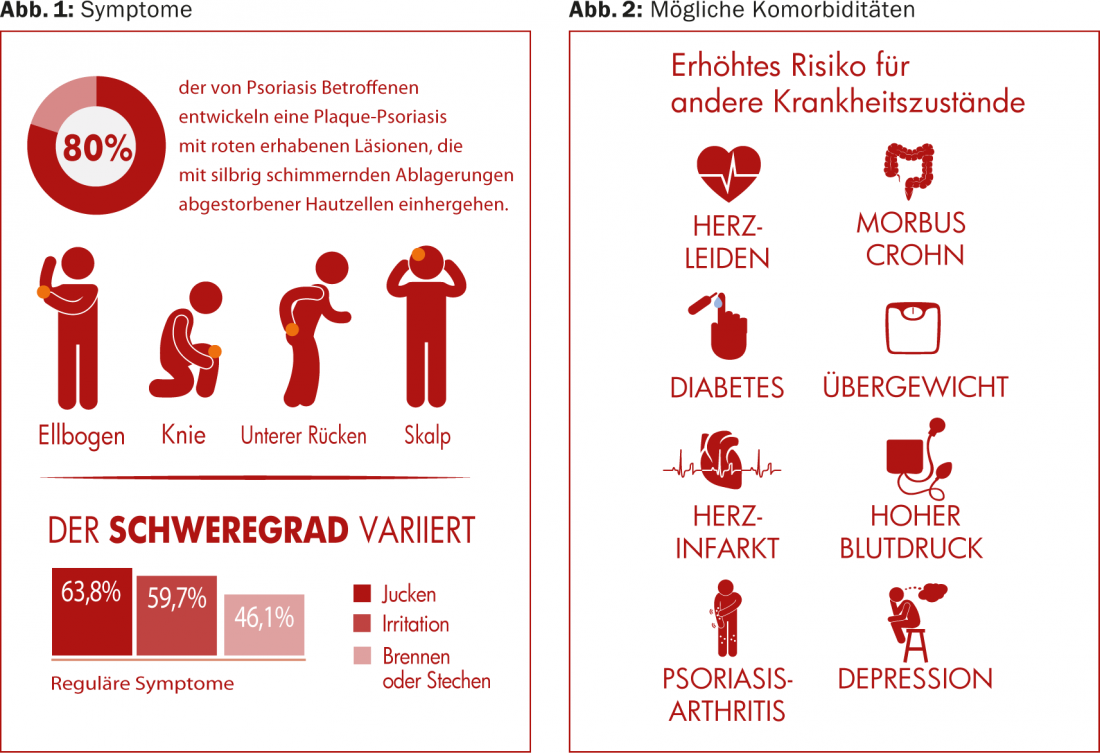

(ag) Psoriasis vulgaris occurs most frequently in this clinical picture (in approx. 80% of all psoriasis cases). It causes red, raised lesions associated with silvery, shimmering deposits of dead skin cells. Most commonly, these are found on the elbows, knees, scalp, and lower back ( Fig. 1) . The prevalence varies widely worldwide, from about 1% of the adult population in the USA, to 8.5% in Norway [1]. The condition often makes itself felt between the ages of 15 and 30. Women are affected almost as often as men, whereas children are affected slightly less often than adults (0 in Taiwan, 2.1% in Italy [1]).

Causes and risks of psoriasis

Although there is no single “psoriasis gene,” experts agree that the disease is most likely genetically determined. However, the genetic predisposition in the overall population is higher than the actual prevalence rate, as only a fraction develops psoriasis, usually triggered by an external trigger such as stress, injury or medication.

Psoriasis carries an increased risk for other health conditions, including cardiovascular disease (atherosclerosis, heart attacks), metabolic syndrome, and other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (psoriatic arthritis, Crohn’s disease) (Fig. 2). Whereas cardiovascular diseases were long thought to be related to obesity and nicotine consumption, which are often also present, rather than to psoriasis per se, there is now debate as to whether the chronic inflammation of psoriasis itself is not more responsible. Psoriasis is particularly often associated with joint inflammation and pain, psoriatic arthritis [2], and skin symptoms may occur several years before joint symptoms.

How does the immune system control inflammation?

It is central to recovery that the immune system is also able to shut down the inflammatory response and return to a state of calm. This is achieved by rebalancing pro- and anti-inflammatory factors [3].

Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) is an enzyme in immune cells that maintains inflammation by lowering the level of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) within the cell [4,5]. It is thus central to the production of proinflammatory factors secreted by many cell types. At the same time, it lowers the production of anti-inflammatory factors.

Although the exact pathways leading to skin inflammation in psoriasis are still under investigation, it is likely that the core of the problem lies in the never-ending inflammatory response, in which PDE4 may play a central role.

ESTEEM 1

Drugs that inhibit PDE4 increase cAMP levels in immune cells, resulting in decreased production of inflammatory mediators (e.g., TNF-α IL-23, IL-17). Thus, by altering the interplay of pro- and anti-inflammatory immune signaling, they can lower inflammation [6].

At this year’s AAD Congress in Denver, Kim Papp, MD, Waterloo, reviewed new results from the randomized, controlled phase III ESTEEM 1 trial [7]. In it, apremilast (APR), an oral PDE4 inhibitor, was studied.

844 patients with moderate to severe psoriasis (PASI ≥12, “body surface area” [BSA] ≥10%, “static Physician’s Global Assessment” [sPGA] ≥3) were randomized 2:1 to placebo (PBO) or APR 30 mg. At week 16, everyone in the placebo group switched to APR. They remained in this until week 32, when all APR patients who had since achieved a PASI-75 were further randomized to either APR 30 mg or placebo (1:1). Upon loss of PASI-75 status, patients previously re-randomized to placebo again took APR.

Results: At week 16, significantly more patients on APR 30 mg had achieved PASI-75 (33.1%) and PASI-50 (58.7%) than those on placebo (5.3 and 17.0%, respectively, p<0.0001). The mean/median percent change in PASI since baseline was -52.1/-59.0% for APR and -16.8/-14.0% for placebo. This difference was also highly statistically significant (p<0.0001).

In general, the changes continued until week 32. Similar PASI responses were achieved this week in those patients who had been switched from placebo to APR 16 weeks earlier.

At the randomized discontinuation phase (week 52), 61.0% of 77 patients randomized to APR at week 32 were PASI-75 responders. In comparison, among patients re-randomized to placebo at week 32, only 11.7% (n=77) achieved such status. In this group, the median time to loss of PASI-75 was 5.1 weeks. After these patients were switched back to APR as described above, a full 70.3% again achieved a PASI-75.

Side effects: Overall, APR was well tolerated for 52 weeks. The number of new side effects did not increase over the weeks. The most common were diarrhea (18.7%), “upper respiratory tract infections” (URTI, 17.8%), nausea (15.3%), nasopharyngitis (13.4%), tension (9.6%), and normal headache (6.5%). Most side effects could be classified as mild to moderate and did not lead to discontinuation of therapy. Severe cases such as infections, malignancy, and cardiovascular events were consistent with previous APR studies.

Conclusion: “Apremilast works well in moderate to severe psoriasis,” Papp said, summarizing the results. “In the randomized discontinuation phase, PASI responses persisted in those patients re-randomized to APR 30 mg. Apremilast also demonstrated an acceptable safety profile and was well tolerated through week 52.”

Source: American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Annual Meeting, March 21-25, 2014, Denver.

Literature:

- Parisi R, et al: Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol 2013 Feb; 133(2): 377-385.

- Mease PJ: Psoriatic arthritis – update on pathophysiology, assessment, and management. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2010; 68(3): 191-198.

- Van Parijs L, Abbas AK: Homeostasis and self-tolerance in the immune system: turning lymphocytes off. Science 1998 Apr 10; 280(5361): 243-248.

- Taskén K, Aandahl EM: Localized effects of cAMP mediated by distinct routes of protein kinase A. Physiol Rev 2004 Jan; 84(1): 137-167.

- Bäumer W, et al: Highly selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors for the treatment of allergic skin diseases and psoriasis. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 2007 Mar; 6(1): 17-26.

- Castro A, et al: Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases and their role in immunomodulatory responses: advances in the development of specific phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Med Res Rev 2005 Mar; 25(2): 229-244.

- Papp K, et al: Apremilast, an Oral Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitor, in Patients With Moderate to Severe Psoriasis: Results From the Randomized Treatment Withdrawal Phase of a Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial (ESTEEM 1). AAD 2014 Poster #8359.

CONGRESS SPECIAL 2014; 5(2): 11-13