Pediculosis pubis is transmitted primarily during sexual intercourse. In scabies, causality is often not present. Nevertheless, both parasitoses are considered possible “sexually transmitted infections” (STI). Sexual partners must therefore also be treated.

Scabies is an infectious disease transmitted by Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis. Transmission occurs via direct skin-to-skin contact, including during sexual intercourse, and less commonly via contaminated items such as bedding, clothing, or towels. Risk factors for transmission include poor sanitation and many people in close quarters, as is most often the case in refugee camps. A scabies epidemic can also spread rapidly in homes and hospitals, especially if the index patient has unrecognized crusty scabies.

The female scabies mite burrows into the epidermis, from which it also feeds. In the tunnels she lays eggs, from which within two weeks first nymphs, later adults emerge. Without its host, the scabies mite dies within 24-36 hours, depending on the ambient temperature and humidity, among other factors.

Just one to five mites are enough to cause the typical scabies symptoms. A cell-mediated late-type (type IV) reaction to mites, eggs or fecal pads is responsible for the eczema reaction with the pronounced, mainly nocturnal itching and papules. In the case of an initial infection, the symptoms therefore only begin after three to six weeks, whereas in the case of reinfection itching can already be expected after one to three days.

Clinic

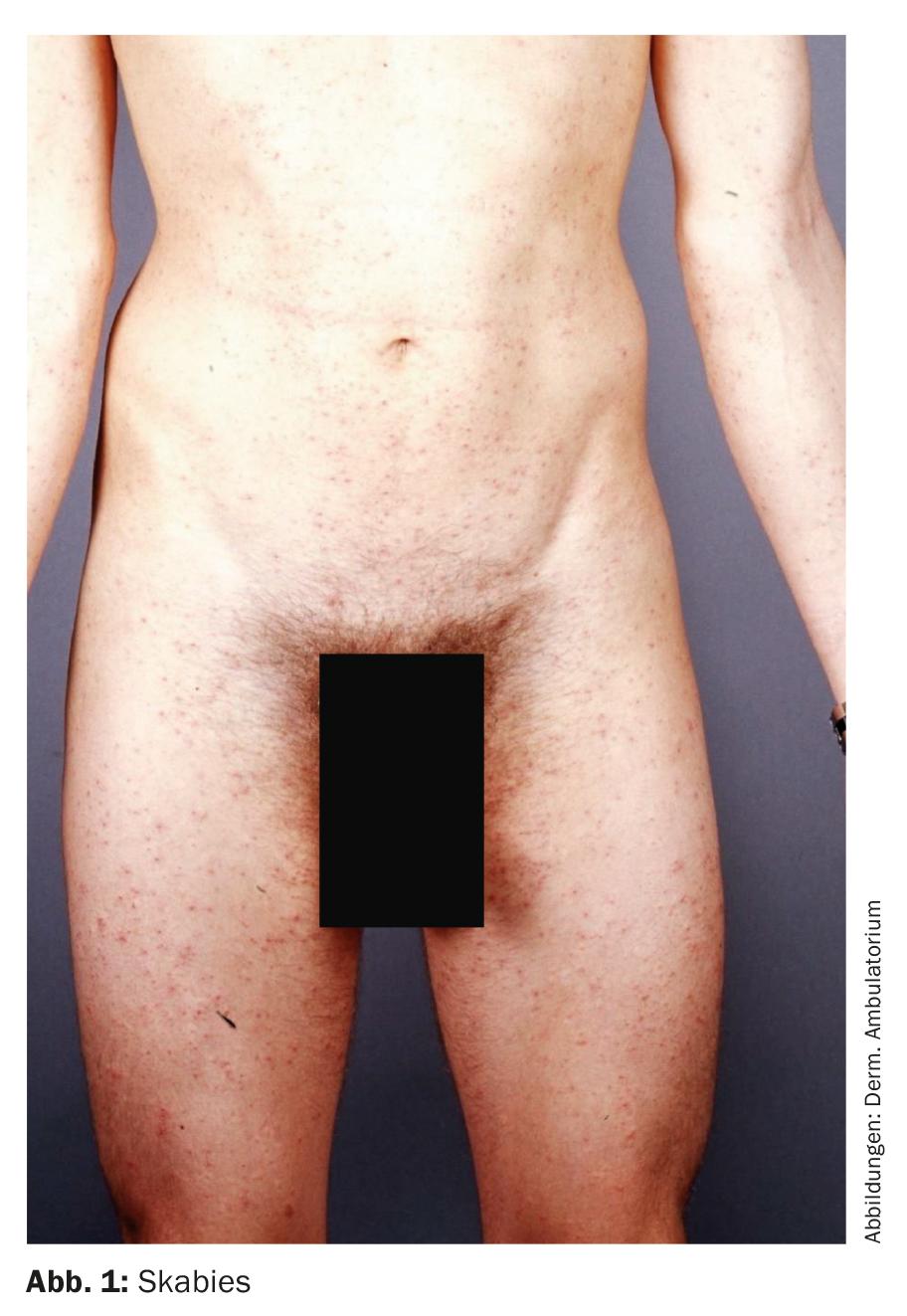

Typically, scabies manifests with intense pruritus and disseminated, small papules (Fig. 1) . Vesicles, secondary eczematization and impetiginization are also possible. In refugees, superinfection with group A β-hemolytic streptococci could often be found.

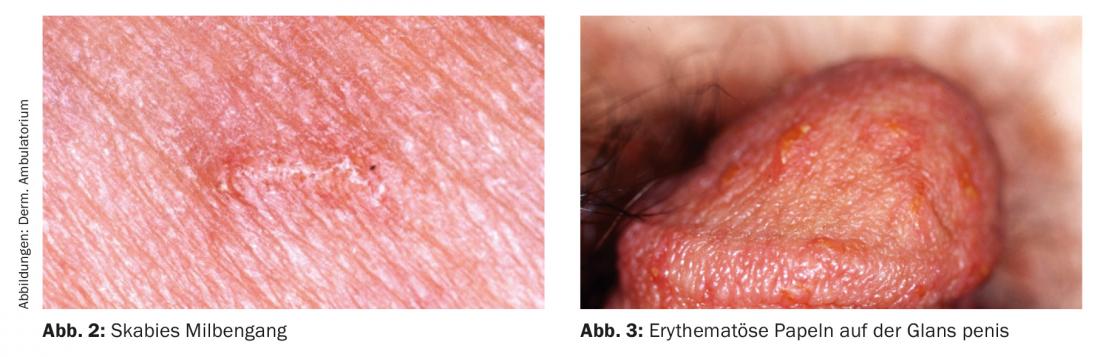

Classic scabies occurs in immunocompetent patients. Intense pruritus with intensification at night is typical. Predilection sites for papules include periumbilical, hip, genital, mammary, buttock, axillary folds, fingers and interdigital spaces, and wrists. In adults, palmae, plantae as well as face are omitted. The primary florescence, a fine gray-brown line 5-10 mm long representing the mite duct (with the mite mound at the end), is rarely observed because it is usually already scratched open (Fig. 2).

Typical erythematous papules on the glans penis are almost pathognomonic for scabies (Fig. 3).

Crusty scabies (formerly scabies norvegica) is seen in patients with immunodeficiency. The generalized scaly, psoriasiform and crusted plaques are associated with comparatively little itching. Bacterial superinfection is common. Crusty scabies is highly contagious.

Diagnosis

The typical history and clinic are usually suggestive. Diagnosis is made by microscopy of scraped skin in the area of the mite mound. With a little luck, mites, more frequently eggs or fecal pads (scybala) can be found in the specimen (Fig. 4) . An alternative method for obtaining material for microscopy is the “superglue method”: A small drop of cyanoacrylate is placed on a microscope slide. The slide is then pressed onto the mite mound and pulled off in a jerky manner after 30 seconds. Microscopy can then be performed.

The dermatoscope can also be used to detect mite ducts, eggs and scabies mites. The so-called delta sign at the end of a duct represents the head and thoracic shield of the mite (Fig. 5).

Clarifications

STI screening is indicated for history of sexual risk behavior.

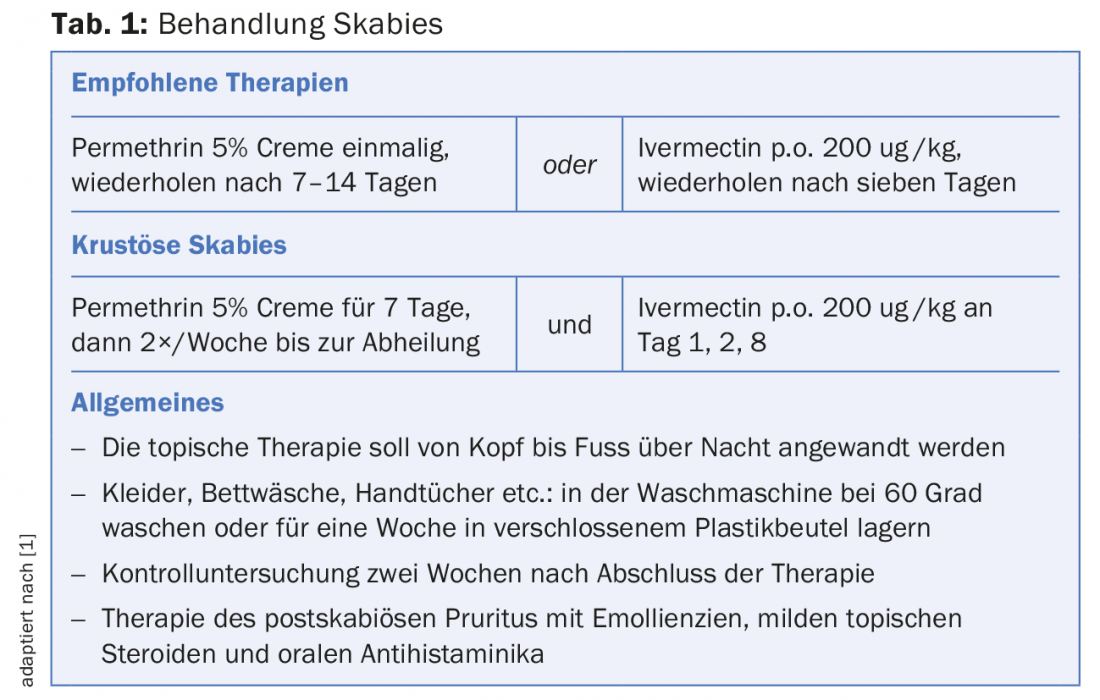

Therapy

Scabies can be treated topically or systemically. For topical therapy, permethrin 5% cream is recommended with the greatest evidence. Permethrin has the advantage that it can also be used without hesitation in infants over two months of age, pregnant women and during breastfeeding. The 5 percent preparation was not available in Switzerland until recently, so it had to be magisterially prescribed or an equivalent preparation ordered abroad. This shortcoming has fortunately been remedied since July 2018 with the market launch of Scabi-med® Creme.

The cream must be applied to dry and cool skin from head to toe and especially in areas such as body folds, external genitalia and interdigital spaces between toes/fingers. After eight to twelve hours, you can take a shower. It is now recommended that both children under the age of three and older people over the age of 60 also have their heads treated, leaving out the eye and mouth area. Due to the low ovocidal effect of permethrin, the current European guidelines also recommend repeating the therapy after seven days.

For systemic therapy, oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg is used, in two doses one week apart, which should be taken two hours before or two hours after a meal. The preparation is not available in Switzerland and must be ordered in Germany or France. Systemic therapy is preferable to topical therapy only in certain situations: failure of prior therapy with permethrin, in immunocompromised patients, and when compliance is not assured for various reasons.

Treatment of crustose scabies must be combined and prolonged (Table 1).

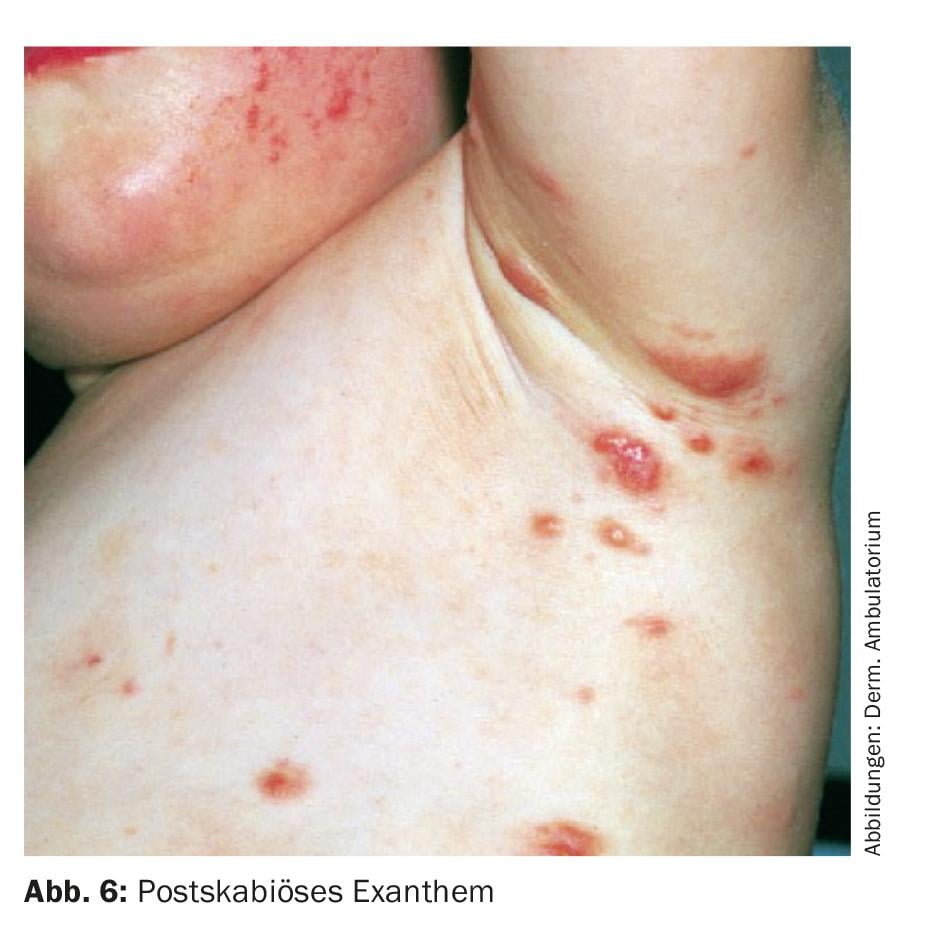

Little documented in the literature is post-scabies exanthema, which can occur mainly in young children after correctly treated scabies in the form of inflamed papules and nodules that persist for weeks (Fig.6). In this situation, it is important to reassure the parents that active scabies is no longer present and to install symptomatic and anti-inflammatory therapy.

Challenges

In the context of the refugee movement of recent years, scabies has gained momentum in Europe. In the refugees’ countries of origin, scabies has a much higher prevalence than in Europe, and conditions during flight favor transmission. If a refugee is diagnosed with classical scabies, isolation of the patient is not mandatory. It is much more important to initiate therapy with permethrin immediately, because the neurotoxic effect on the scabies mite means that there is no longer any risk of infection after permethrin has been applied.

In this context, case reports from Australia of documented resistance to permethrin are unsettling, although no reports of resistance have yet appeared outside Australia.

Pediculosis pubis

Pediculosis pubis, along with pediculosis capitis and pediculosis corporis, is an infestation with parasites caused by one of three variants of lice that are obligately human pathogens. What they all have in common is that they can spread in confined living conditions with poor sanitation, such as in war zones or refugee homes.

However, the main transmission mechanism of pediculosis pubis – in contrast to the other two louse diseases – is sexual contact, which is why this parasitosis is considered a “sexually transmitted infection” until proven otherwise, which has an impact on the investigations and co-treatment of sexual partners.

Epidemiology

Until a few decades ago, crabs were a common disease. They occur worldwide, but the incidence in the Western world has decreased markedly and infestations with crabs are seen only very sporadically. In the Dermatological Outpatient Clinic of the Triemli City Hospital, approximately one to three patients per year are still treated against crabs. Often, these patients have contracted the disease abroad.

The reasons for the decline of this parasitosis are on the one hand the improved hygienic conditions, but on the other hand mainly the fact that a changed fashion consciousness has led to the fact that more and more people in the western industrial nations remove their underarm, leg and pubic hair. As a result, the habitat of the crab louse is increasingly disappearing. A British study showed that the prevalence of Phthirus pubis decreased significantly between 1997 and 2003, while the prevalence of chlamydial and gonococcal infections increased during the same period. Because the decrease cannot be attributed to a change in sexual behavior based on these data, the authors hypothesize that the advent of “waxing” techniques for genital hair removal is responsible for the decrease in crabs.

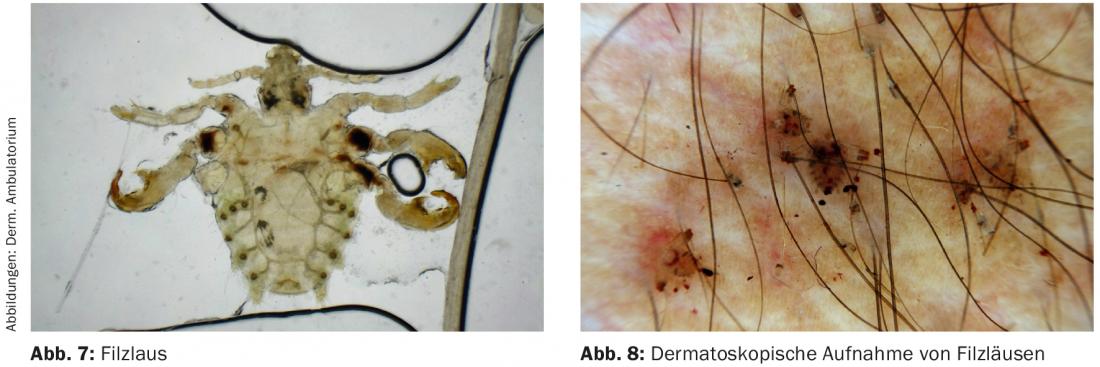

Fungal louse transmission occurs primarily through close physical contact, typically during sexual contact. Infection through contaminated bed contents, clothes or bath towels is possible, but rather the exception, because, among other things, the louse can survive without a blood meal only about 24 to a maximum of 48 hours outside the human body. Sexual contact results in transmission of the parasites, which spread in the terminal hairs of the pubes and perianal region. The broad physique of the crab louse with its three pairs of legs is optimally designed for clawing its way into the strong and widely spaced pubic hairs (Fig. 7) . In contrast, it can hardly crawl, yet it can spread to the body hair.

The incubation period is usually less than a week. Likewise, it takes a week for nymphs to hatch from eggs laid by adults. At 1.5-2 mm in size, the aphids are just visible to the naked eye (Fig. 8).

Clinic

The infection is initially not noticed in the majority of cases. It is only through the blood meals of the lice that pruritus occurs, which is the leading symptom. Erythematous macules/papules are found at the sting sites, but the bluish spots (maculae coeruleae) rarely occur. Occasionally, small traces of blood are also found on the underwear.

In addition to the genital and perianal regions, the lice can also be found on other hairy areas of the body, and rarely on the eyelashes and eyebrows.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made on the basis of the typical clinic with crabs or nits identified by the naked eye or by dermoscope.

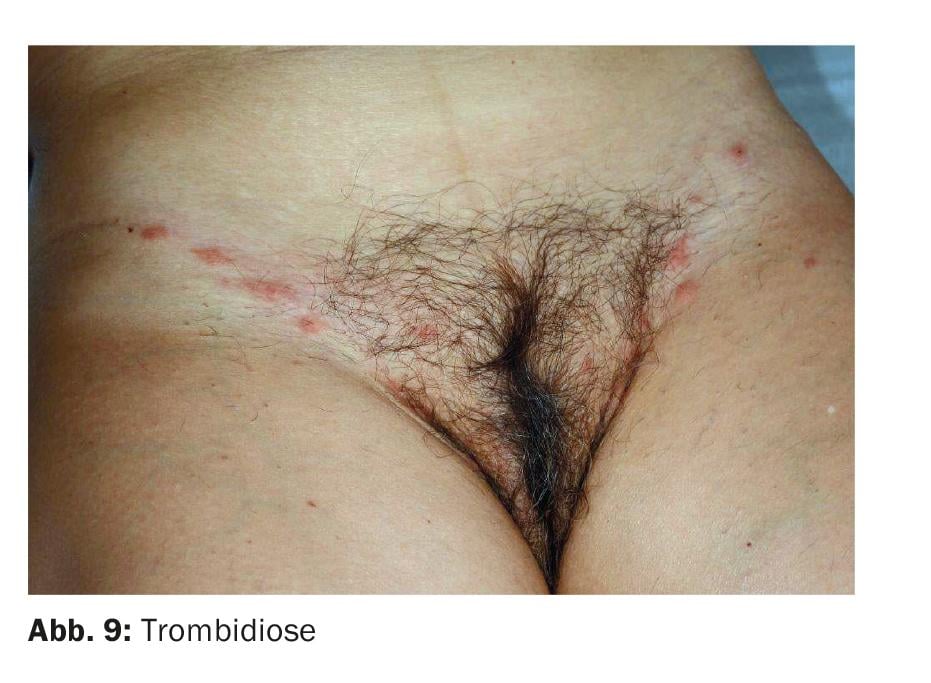

Differential diagnosis may include trombidiosis, because the stinging reactions of these mites preferentially occur in the warm, moist genital region (Fig. 9).

Clarifications

The guidelines clearly recommend excluding concomitant STIs, which can be found in up to 30%. At least one HIV and syphilis test should be performed, and in principle a PCR examination for chlamydia and gonococci should also be included.

Therapy

As with scabies, the first-line therapy for pediculosis pubis according to the European guidelines is permethrin, with the 1% formulation being sufficient for crab lice. In Switzerland, Loxazol® is available as a ready-to-use product. The rinsing lotion should be left on for over ten minutes, after which it can be rinsed off. After seven to ten days, the therapy should be repeated again. Permethrin can also be used during pregnancy. Alternatively, malathion (Prioderm®) can be used as local therapy instead of permethrin.

In cases of massive and extensive crab lice infestation or failure of local therapy, ivermectin (Stromectol®) is available as an “off-label” therapy. It must be obtained from abroad, which is why a cost approval should be obtained from the health insurance company in advance. The usual dosage is 200 µg/kg body weight as a single dose. Also with this drug, another therapy is recommended after seven days.

If the eyelashes are affected, Vaseline should be applied 2×/day. This suffocates the lice and they can be removed from the eyelashes together with the nits using tweezers.

It is important to treat all sexual partners at the same time. All participants should refrain from sexual intercourse until evidence of successful therapy is available one week after the last treatment.

Shaving of genital hair is not necessary for successful therapy. After therapy, worn clothes, bed linen, terry cloths, etc. must be washed at a minimum of 60 degrees or dried in a tumble dryer. Alternatively, garments can be stored in a sealed plastic bag for three days.

Literature:

- Salavastru CM, et al: European guideline of the management of scabies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31: 1248-1253.

Further reading:

- Neynaber S, et al: Use of superficial cyanoacylate biopsy (SCAB) as an alternative for mite identification in scabies. Arch Dermatol 2008; 144; 114-115.

- Di Meco E, et al. : Infectious and dermatological diseases among arriving migrants on the Italian coasts. Eur J Public Health 2018 Oct 1; 28: 910-916.

- Salavastru CM et al: European guideline of the management of pediculosis pubis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31: 1425-1428.

- Armstrong NR, et al: Did the “Brazilian” kill the pubic louse? Sex Transm Infect 2006; 82: 265-266.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018; 28(6): 16-21