Adolescents are difficult, don’t want to go to therapy, are unmotivated, are non-compliant: this is our common image of chronically ill adolescents. Is that really so? Or maybe it’s the way we as healthcare professionals interact with this age group. Using bronchial asthma as an example, the article is intended to demonstrate facts, awaken understanding for this “special group of patients” and show feasible ways of winning over the young people and thus leading them to a self-responsible and sufficient therapy.

Adolescents are difficult, don’t want to go to therapy, are unmotivated, are non-compliant: this is our common image of chronically ill adolescents. Is that really so? – Or maybe it’s the way we as healthcare professionals interact with this age group. The following article is intended to show facts using the example of bronchial asthma, to arouse understanding for this “special group of patients” and to show feasible ways to win over the young people and thus to lead them to a self-responsible and sufficient therapy.

Life phase youth – a challenge even without asthma

Young people are in a “transition phase.” This is understood to mean crisis-like, time-limited phases in the development of people that are triggered by first-time or one-time striking events. A distinction is made between “normative transitions” and “non-normative transitions”. Normative transitions are developmental phases that almost all people go through in the course of their lives, such as entering kindergarten, starting school, puberty, entering the workforce, etc. In addition, there are so-called “non-normative transitions”. These are individual incisions such as changes in the social environment, sudden losses, “strokes of fate” or changes in medical and therapeutic care structures for chronic diseases such as bronchial asthma.

It is not adolescents as such who are difficult, they are in a difficult phase of life

Adolescents are in the normative transition phase of pubertal identity formation. They are not “little adults”, nor are they “big kids”. During puberty, they have the “task” of breaking away from their parents, opposing, exploring boundaries and learning independence – sometimes quite confrontationally. However, in addition to puberty as a “normal” transition period for any person, chronically ill adolescents must also manage the process of transitioning into “adult medicine” – a simultaneous “non-normative transition” as a double challenge. Transition here means not simply changing doctors, but the entire process of growing up and taking responsibility for the disease. In this process, we should support the young people. Awareness of this dual challenge should guide our thinking and actions when dealing with young people.

Our task in the accompaniment of adolescents with asthma

Adolescents with chronic diseases are perceived by many as a “difficult patient group”, as they sometimes do not feel like taking medication regularly and are rather annoyed by it. The aim is to take adolescents seriously in their life situation, to generate concern and thus to provide them with the necessary knowledge and skills to take over the self-management of their disease. In children and adolescents, allergic diseases are among the most common health impairments. The 12-month prevalences for hay fever (8.8%), neurodermatitis (7.0%), and bronchial asthma (3.5%) show no significant changes over several years, indicating a stabilization of disease frequencies at a high level [1]. The data also show that adolescents rate their health worse than their parents do and that chronic conditions such as asthma have a negative impact on adolescents’ quality of life.

Compliance or adherence: participatory decision making.

Whereas in the past the term “compliance” was used, i.e. the “ordering” of a measure by the physician and the “following” of this order by the patient, today the term “adherence” is used. Adherence in medicine stands for adherence to the therapy goals set jointly by the patient and the healthcare professionals (physicians, nurses, therapists). The concept of adherence is based on the recognition that adherence to treatment plans, and therefore treatment success, is the shared responsibility of the healthcare professional and the patient. Therefore, both sides should “work together” as equally as possible and make joint decisions on an equal footing.

A 2009 cohort study of 102 randomized children and adolescents assessed adherence to inhaled medications every 2 months for 12 months using 4 different methods. While 98% of the prescribed doses were inhaled according to self-reporting by patients or parents, and 70% of prescriptions were still filled in pharmacies, the “more objective” methods such as electronic measurement of the inhalation rate or weighing of the metered dose inhaler showed completely different results. Here, the actually measured “compliance rate” was only about 50% [2].

This result correlates with various other studies and has not changed significantly in recent years, as shown by Milgrom’s 1996 data and also by other authors [3]. Unfortunately, even more recent studies do not show significantly better values [4]. Even within the adolescent group, younger patients appear to have better treatment adherence than older adolescents, as shown in a 2009 study [5]. This may be explained by the even greater influence of the parents.

Furthermore, data show that there is a clear correlation between “compliance” and disease duration: the longer the disease, the worse the compliance [2].

Lack of adherence and its impact on asthma control.

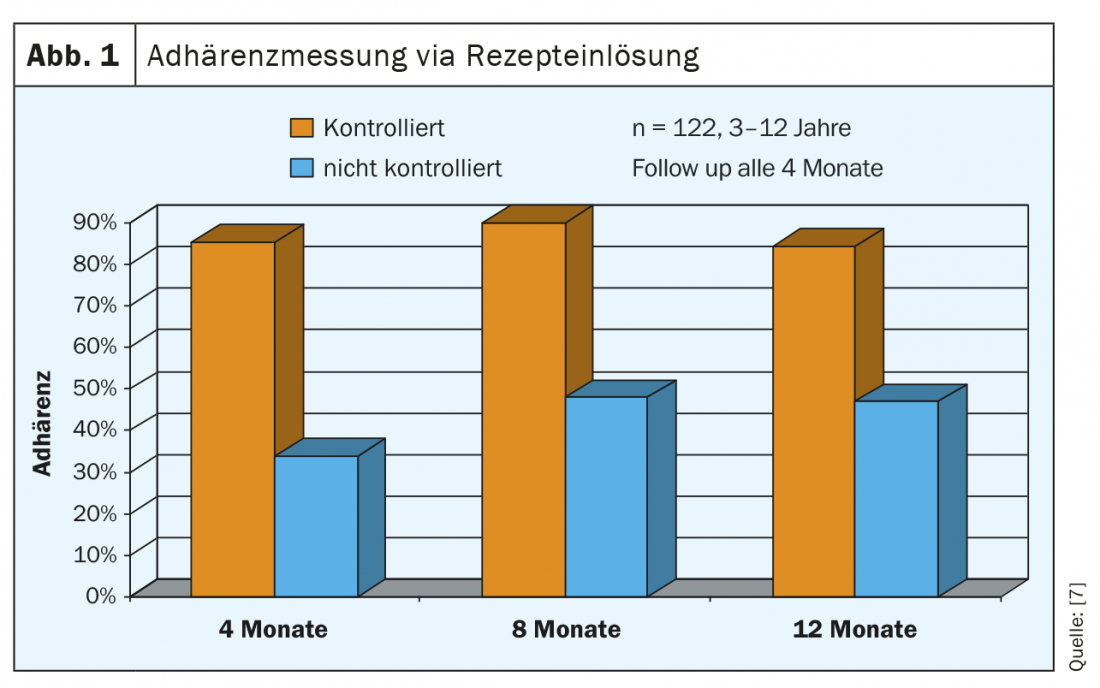

The therapeutic goal according to guidelines [6] is controlled asthma, i.e. in children and adolescents complete freedom from symptoms without the use of emergency medication with normal daily activities and unrestricted social participation. The present data (Fig. 1) show a strict correlation -between therapy adherence and the therapy goal asthma control [7]. These data were again impressively confirmed in 2015 in -a systematic review with 23 included studies: Although study measures varied significantly, good adherence was associated with fewer severe asthma exacerbations in high-quality studies [8].

Adolescents are honest: they say why they don’t do the therapy: While younger children often let their parents do the talking in the doctor’s interview, and adults often give doctors the “desired” answers rather than the real ones, adolescents are much more honest here. They openly say why they didn’t do something – whether “forgot” or “didn’t feel like it” or “I’m doing so well after all” – all of these are classic answers to our question, “How regularly did you inhale?”

However, it is also important to consider the role of parents with adolescents as well. It is by no means the case that they completely lose their influence. Rather, some adolescents continue to rely on parents, leaving them with some of the responsibility for therapy [9].

What factors specifically lead to less adherence to therapy in adolescents?

In a systematic review published in 2020 [10], the authors conclude the following adolescent-specific reasons:

- Desire for independence and responsibility including rejection of parental supervision and support.

- Conflicts with parents about who is responsible for the correct implementation of therapy

- Difficulties in “time management” and setting priorities

- “Forgetfulness” or the perception of having too much else to do

- Lack of decision-making ability: do I take the medication or not?

- Lack of knowledge about effect and side effect to induce decision-making ability

- Leaving the responsibility for therapy with the parents combined with a lack of parental “motivation”.

- Conflict of interest between taking medications and other daily activities.

- Lack of perception of the therapeutic effect

- Shame before friends

- Adolescent “risky behavior” such as smoking, alcohol or drugs

- Increased influence of mental disorders in adolescents

Specifically, what external factors lead to more treatment adherence in adolescents [11,12]?

- Functioning family structure and realistic assessment of the situation. Asthma

- Low perceived stress in education and regular therapy

- Routine (=ritualized?) therapy

- Maximum 2 inhalations per day

- Recent exacerbation

- Conviction regarding self-efficacy

- Positive basic mood

- Clear structured daily routines in the family

- Clear distribution of tasks re. the therapy

- Older parents

What training measures are helpful?

In general, it can be said: Training of adolescents improves therapy adherence. In addition to traditional outpatient or inpatient training or rehabilitation, new, alternative forms of training have also been shown to be effective. Several meta-analyses have already demonstrated their effectiveness at various levels since 2003 -[13 –15]. Significantly, the following results emerged:

- Improvement of lung function (PEF +9.5%)

- Reduction of school absenteeism

- Improvement of physical activity

- reduced nocturnal asthma attacks

- reduced hospital stays

- Reduced emergency room visits

- Strengthening of self-confidence – to stand by one’s illness and not to be alone with it.

In addition to these classic training concepts, other training concepts on an online basis or as apps [16,17] were also evaluated. These also showed positive results regarding treatment adherence in adolescents. However, whether this form of training reaches the participants as individually as in a live training [18] must be critically questioned. Comparative data are not available.

What can WE do in providing individualized care to youth?

Especially with adolescents, a good discussion atmosphere and doctor-patient relationship are crucial for the motivation to carry out the therapy. Young people often experience being told “from the outside” what they should and should not do. However, they already feel that they are self-determining individuals. This often leads to conflicts or to behavior in which the young people, out of opposition, do not do what they are told from the outside.

Adolescents should feel that they are being “counseled” but are making the decisions for their own behavior. Here, the topic of “adherence to therapy” and “feasibility” should be addressed openly and thus a joint therapy decision should be made together with the adolescent [19]. The choice of inhaler should also be made together with the adolescent. A “feedback system” regarding treatment adherence is also helpful. This improves both measured compliance and objective pulmonary function parameters [20].

Psychosocial contextual factors of adherence in children and adolescents.

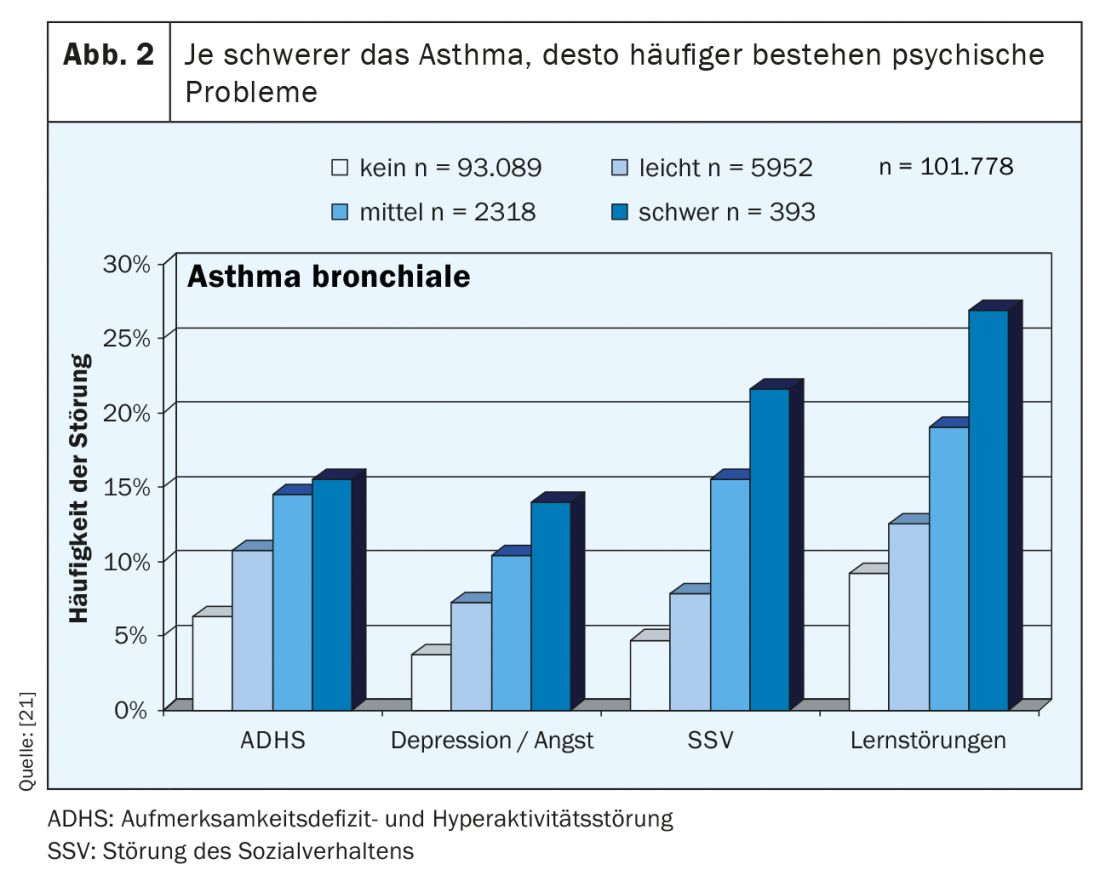

At the latest since the evaluation of large population-based studies in the USA in 2007, it has been known that the frequency of psychosocial abnormalities in children and adolescents increases with the severity of asthma. At that time, bronchial asthma was (still) classified as mild, moderate, and severe. This shows a significant increase in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depressive/anxiety disorder, social behavior disorder, and learning disorder depending on the severity of bronchial asthma [21] (Fig. 2). This can also be demonstrated in data from the United Kingdom [22]. When the study data from the United States are viewed from the perspective of the particular mental disorder, the presence of the mental disorder in each case results in a significantly increased proportion in children and adolescents with bronchial asthma. Thereby, the frequency of bronchial asthma almost doubles in the presence of such a disorder.

Similar results were obtained in a meta-analysis in 2001 with a total of 26 studies [23]. All in all, therefore, we can assume that our knowledge is certainly well-founded. Despite these clear associations, there are surprisingly few studies devoted to the topic of adherence in the presence of a mental disorder.

One possible explanation for the association between mental abnormality and asthma would be that the mental abnormalities are a consequence of drug therapy. This can be clearly ruled out, at least for the active ingredient of inhaled corticosteroids. A children’s study showed that children with good adherence (average 92%) to inhaled corticosteroids did not have increased behavioral problems as measured by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [24]. However, regarding the leukotriene antagonist montelukast, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published a so-called “boxed warning” in March 2020, explicitly listing agitation, depression, sleep disturbance, as well as suicidal thoughts as side effects [25].

Especially in patients with an unfavorable course regarding bronchial asthma, increased behavioral abnormalities can be expected. Here, the use of leukotriene antagonists should be particularly cautious.

Asthma and ADHD

The co-occurrence of bronchial asthma and ADHD has been demonstrated not only in the studies mentioned above. The RKI data (Germany-wide population-based study) show (own analysis, not published) a prevalence of ADHD in children with bronchial asthma of 7.8%; the prevalence of ADHD in the group without bronchial asthma is 4.7% -(n=13 292). Conversely, in the group of asthmatics significantly more children with conspicuous values show hyperactive behavior (11.8% versus 8.4%, n=14 300).

The impact of ADHD on adherence in children and adolescents has not been the focus of a single study. However, when the typical symptoms of ADHD with inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity are contrasted with the need to treat bronchial asthma, clear evidence emerges that attention deficit hyperactivity disorder interferes with optimal therapy for bronchial asthma. The regular implementation of continuous therapy, the possibly necessary control of physical activity, the avoidance of triggers as well as the social competence in dealing with the disease do not fit the picture of ADHD. This makes it all the more urgent to provide optimal treatment not only for bronchial asthma but also for ADHD in order to do justice to the patients as a whole.

Asthma and social behavior disorder

The situation is similar with regard to the comorbidity of bronchial asthma and social behavior disorder. Here, too, the typical symptoms of social behavior disorder (frequently quarrels with adults, resists adult rules, easily reacts sensitively and angrily) and the necessities of bronchial asthma treatment result in difficulties in therapy implementation – especially if regimentation of behavior is demanded from the adult side, this quickly leads to oppositional behavior and poor asthma management. Our own studies [26] have shown that the need for support in bronchial asthma increases with the extent of externalizing behavioral problems. That is, these children need extra support to implement the necessities of the treatment of their bronchial asthma as well as possible.

Asthma and depression/anxiety disorder

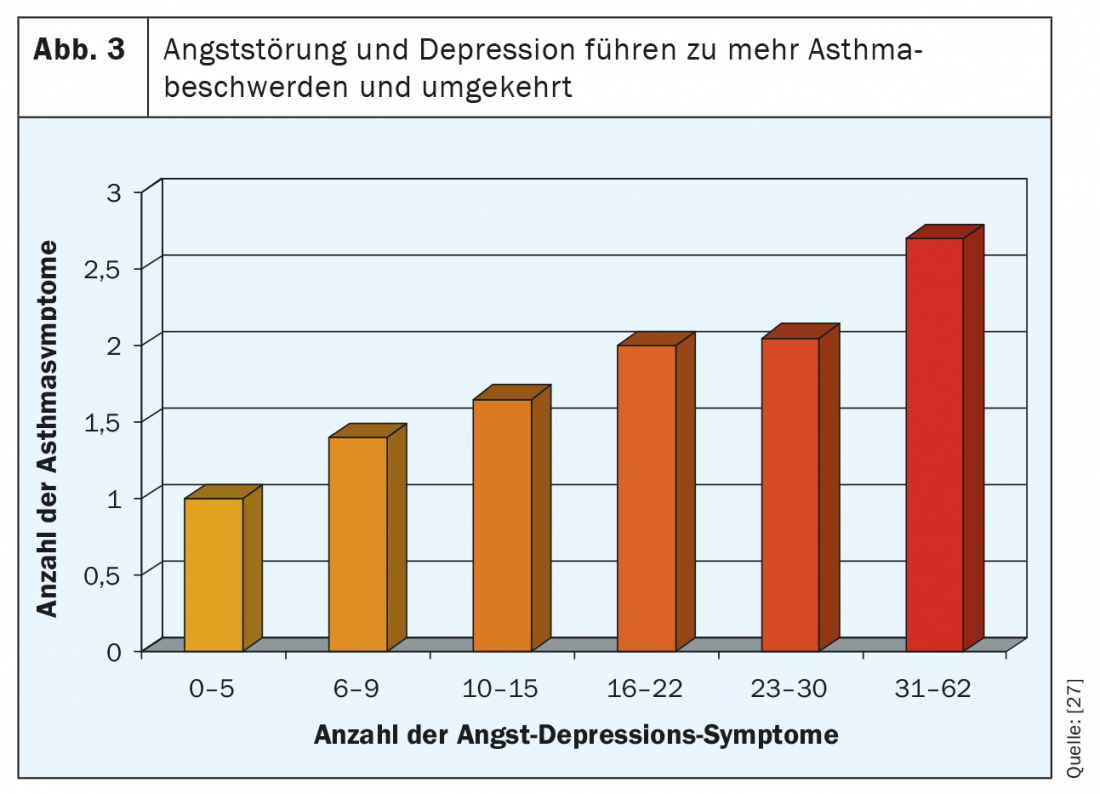

For anxiety disorder and depression, the overall data situation is better. In 2006, in a population of over 700 children and adolescents aged 11 to 17 years, a clear correlation between the number of anxiety/depression symptoms and bronchial asthma symptoms was found [27]. The more anxiety/depression symptoms there are, the more asthma symptoms there are and vice versa (Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained in a recent study from 2021 [28], which showed a similar effect, especially in girls.

In a study of children and adolescents (8-18 years old), adherence was assessed with respect to. of asthma therapy in the presence of depression/anxiety disorder and bronchial asthma [29]. Here, too, there was a clear correlation between the extent of anxiety/sadness and asthma symptoms. However, this association could not be explained by nonadherence. This appears to be an independent context. It is discussed that with increased anxiety and sadness, there is also an increased perception of asthma symptoms. This study also demonstrates that non-adherence leads to unstable bronchial asthma with the need for systemic steroid therapy.

However, in adult patients with bronchial asthma and depression [30], a clear relationship between the level of depressive symptoms and adherence was measured. The odds ratio – that is, the risk – regarding poor adherence (taking less than 50% of agreed medications) is increased 11.4-fold with a significantly elevated depression score. In this study, apathy; pessimism about the effectiveness of therapy; acute deficits in attention, memory, and receptivity; intentional self-harm; and heightened concerns about possible side effects were discussed as possible causes of poor compliance in the presence of marked depressive symptomatology.

Psychosomatic and social contextual factors

Overall, it can thus be clearly depicted that psychosocial abnormalities, in particular ADHD, social behavior disorder, and depression, are associated with inadequate asthma management. In the presence of these diseases, in addition to optimal asthma therapy, optimal therapy and treatment of the respective underlying psychosocial disease is also required. Cooperation between the treating pediatrician and psychologist or child and adolescent psychiatrist is necessary here. A joint exchange about the patient can certainly optimize the therapy of both diseases and is clearly to be demanded. As shown above, both diseases negatively influence each other.

Summary

Nonadherence is an important, if not the most important, cause of unstable bronchial asthma, i.e., uncontrolled or only partially controlled. Poor adherence, (that is, taking less than 75% to 80% of the agreed medications), must be expected in at least 50% of all patients, but especially in patients in whom asthma control is not achieved to the extent expected.

Therapy for non-adherence includes structured patient education and long-term collaboration between the patient and the treating physician to improve adherence. In this context, the belief in the benefits of therapy – especially in the experience of a therapeutic effect – is particularly effective.

It is important to have understanding: It is not the adolescent with asthma per se who is “difficult” but the situation in which they find themselves. Young people must be valued and taken seriously. They need perspectives and need to see the added value of therapy for their personal situation. In the conversation, it is the adolescent who is the contact person, not his or her parents, although the parents continue to have an important function as “companions” in their role as advisors. The motivation for therapy must come from the adolescent, not from the parents or the doctor, which means that we as doctors must not overestimate our own role. In any consultation, we should ask openly: young people give honest answers.

Bronchial asthma is associated with increased rates of internalizing and externalizing disorders. In this context, unfavorable psychosocial behavioral characteristics lead to poor asthma management and non-adherence. The need for support due to bronchial asthma increases with the extent of externalizing behavioral problems.

Take-Home Messages

- Young people are honest: they say why they don’t do the therapy.

- Nonadherence is an important, if not the most important, cause of unstable bronchial asthma, i.e., uncontrolled or only partially controlled.

- In the conversation, it is the adolescent who is the contact person, not his or her parents, although the parents, as advisors, still have an important function as “companions.”

- The need for support due to bronchial asthma increases with the extent of externalizing behavioral problems.

Literature:

- Thamm R, Poethko-Müller C, Hüther A, Thamm M: Allergic diseases in children and adolescents in Germany – cross-sectional results from KiGGS wave 2 and trends. Journal of Health Monitoring, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin 2018.

- Jentzsch N, Camargos E, Colosimo E, Bousquet J: Monitoring adherence to beclomethasone in asthmatic children and adolescents through four different methods. Allergy 2009 Oct; 64(10): 1458-1462.

- Milgrom H, Bender B, Ackerson L, et al: Noncompliance and treatment failure in children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996 Dec; 98(6 Pt 1): 1051-1057.

- Morton RW, Elphick HE, Rigby AS, et al: STAAR: a randomised controlled trial of electronic adherence monitoring with reminder alarms and feedback to improve clinical outcomes for children with asthma. Thorax 2017; 72 (4): 347-354.

- German Medical Association (BÄK), National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (KBV), Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF). National health care guideline on asthma – long version, 4th edition. Version 1. 2020 (www.asthma.versorgungsleitlinien.de).

- Naimi D, Freedman T, Ginsburg K, et al: Adolescents and asthma: why bother with our meds? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 123: 1335-1341.

- Lasmar L, Camargos P, Champs N, et al: Adherence rate to inhaled corticosteroids and their impact on asthma control. Allergy 2009 May; 64(5): 784-789.

- Engelkes M, Janssens H, de Jongste J, et al. Medication adherence and the risk of severe asthma exacerbations: a systematic review. Eur Respir J 2015 Feb; 45(2): 396-407.

- Desai M, Oppenheimer J: Medication adherence in the asthmatic child and adolescent. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2011; 11: 454-464.

- Kaplan A, Price D: Treatment Adherence in Adolescents with Asthma. Journal of Asthma and Allergy 2020; 13: 39-49.

- Drotar D, Bonner M: Influences on adherence to pediatric asthma treatment: a review of correlates and predictors. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2009.

- Gray W, Netz M, McConville A, et al: Medication adherence in pediatric asthma: A systematic review of the literature. Pediatric Pulmonol 2018 May; 53(5): 668-684.

- Guevara J, Wolf F, Grum C, Clark N: Effects of educational interventions for self-management of asthma in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2003 Jun 14; 326(7402): 1308-1309.

- Coffman J, Cabana M, Halpin H, Yelin E.: Effects of asthma education on children’s use of acute care services: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2008 Mar; 121(3): 575-578.

- BoydToby M, Lasserson T, McKean M, et al: Interventions for educating children who are at risk of asthma-related emergency department attendance. Cochrane Systematic Review Version published: 15 April 2009.

- Ramsey R, Plevinsky J, Kollin S, et al: Systematic Review of Digital Interventions for Pediatric Asthma Management. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020 Apr; 8(4): 1284-1293.

- Alquran A, Lambert K, Farouque A et al: Smartphone Applications for Encouraging Asthma Self-Management in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018; 15(11): 2403.

- Arbeitsgemeinschaft Asthmaschulung im Kindes- und Jugendalter e.V. Quality management in asthma training for children and adolescents. iKuh Verlag, 5th edition 2019.

- Burgess S, Sly P, Morawska A, Devadson S: Assessing adherence and factors associated with adherence in young children with asthma. Respirology 2008; 13: 559-563.

- Burgess S, Sly P, Devadson S: Providing feedback on adherence increases use of preventive medication by asthmatic children. J Asthma 2010 Mar; 47(2): 198-201.

- Blackman JA, Gurka MJ: Developmental and behavioral comorbidities of asthma in children. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2007; 28: 92-99.

- Calam R, Gregg L, Goodman R: Psychological Adjustment and Asthma in Children and Adolescents: The UK Nationwide Mental Health Survey. Psychosom Med 2005; 67 (1): 105-110.

- McQuaid EL, Kopel SJ, Nassau JH: Behavioral adjustment in children with asthma: a meta- J Dev Behav Pediatr 2001; 22(6): 430-439.

- Quak W, Klok T, et al: Preschool Children With High Adherence to Inhaled Corticosteroids for Asthma Do Not Show Behavioural Problems. Acta Paediatr 2012; 101 (11): 1156-1160.

- FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA requires Boxed Warning about serious mental health side effects for asthma and allergy drug montelukast (Singulair®); www.fda.gov/media/135840/download (accessed 3/30/2021).

- Goldbeck L, Koffmane K, Lecheler J, et al: Disease severity, mental health, and quality of life of children and adolescents with asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol 2007 Jan; 42(1): 15-22.

- Richardson LP, Lozano P, Russo J, et al: Asthma symptom burden: relationship to asthma severity and anxiety and depression symptoms. Pediatrics 2006 Sep; 118(3): 1042-1051.

- Kulikova A, Lopez J, Antony A, et al: Multivariate Association of Child Depression and Anxiety with Asthma Outcomes. J Allergy Immunol Pract 2021 Mar 4; 21: 2213-2198.

- Bender B, Zhang L: Negative Affect, Medication Adherence, and Asthma Control in Children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 122 (3): 490-495.

- Smith A, Krishnan JA, Bilderback A, et al: Depressive symptoms and adherence to asthma therapy after hospital discharge. Chest 2006 Oct; 130(4): 1034-1038.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2021; 3(2): 4-9.