10-15% of the population suffer from daytime sleepiness. Causes include socially induced sleep deprivation, shift work, or diseases such as sleep apnea syndrome, narcolepsy and other hypersomnias, restless legs syndrome, parasomnias, insomnias with secondary daytime sleepiness, or medication use. Drowsiness at the wheel (inattention, “tunnel vision” and prolonged reaction time) always precedes sleep and may cause 10-30% of all traffic accidents. Effective countermeasures are stopping, drinking coffee, turbo sleep. All professional drivers with daytime sleepiness and all drivers who have already been in an accident should be referred to a sleep medicine center. In the case of undiscerning patients, the physician in Switzerland has the right, but not the obligation, to file a complaint with the authorities.

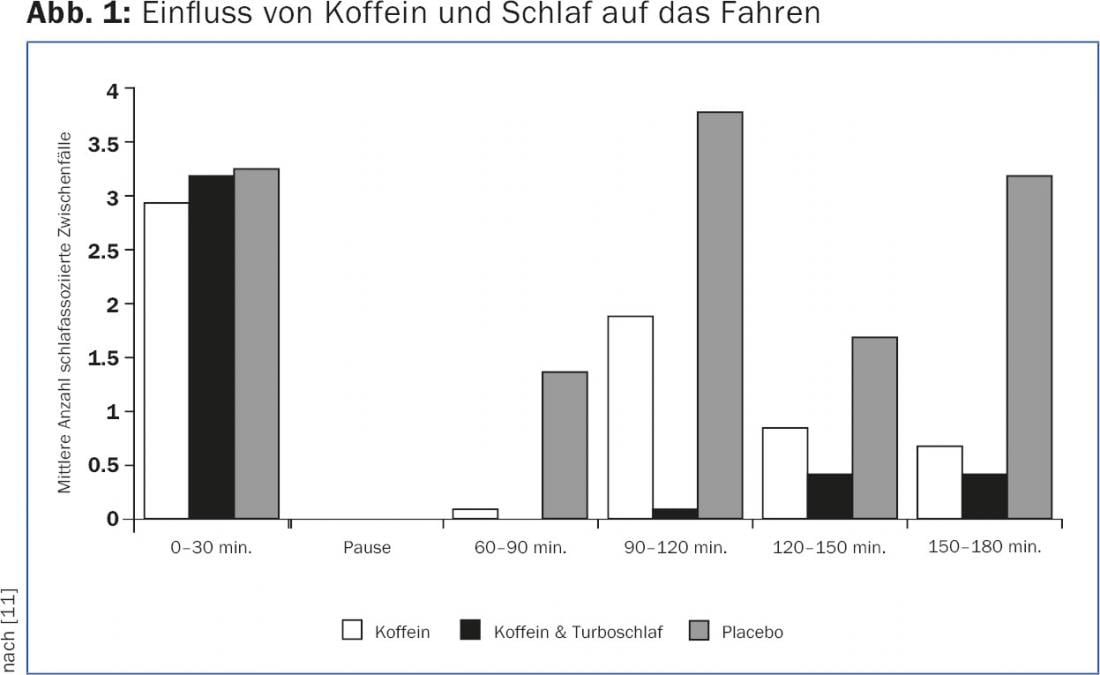

In industrialized nations, 10-15% of the population suffers from daytime sleepiness [1]. The typical signs of sleepiness are frequent yawning, blurred/double vision, irresistible urge to close the eyes, impaired ability to concentrate, and decreased activity (e.g., forgetting to look in the rearview mirror). These warning signals always precede falling asleep at the wheel [2–4]. Accordingly, 50% of vehicle drivers surveyed reported driving drowsy in the past year, 30% had drowsiness-related near-misses, and 20% even fell asleep while driving [1]. In addition, drivers are usually unaware that countermeasures such as listening to music at a high volume, opening the window pane, smoking, or chewing gum are only effective for 15-20 minutes and are thus insufficient to prevent falling asleep [5]. The only effective measure is to stop immediately. Then you should first drink a coffee and then sleep for 15 minutes (turbo sleep, Fig. 1) [1].

Accordingly, drowsiness is suspected to be the cause of 10-30% of all motor vehicle accidents, although this is mentioned in accident reports in Switzerland – as in other countries – with a share of only 1.5% [1]. This discrepancy is most likely related to the fact that, on the one hand, drivers do not remember or deny prior drowsiness [1] and, on the other hand, traffic police find another reason such as driving under the influence of alcohol. Most accidents involving drowsiness are accompanied by serious consequences.

Causes of sleepiness

Patients with sleep apnea syndrome, narcolepsy, restless legs syndrome, or insomnia with secondary daytime sleepiness are particularly at risk for increased sleepiness, as are patients who must take sleeping pills or sedating medications.

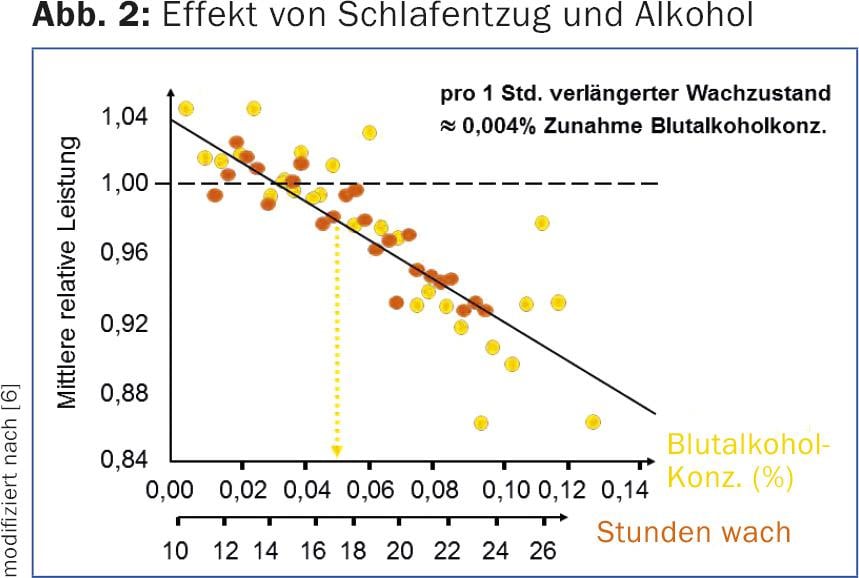

In healthy individuals, socially or occupationally induced sleep deprivation or an unfavorable sleep-wake rhythm (e.g. shift work) often leads to daytime sleepiness. Interestingly, 24 hours of sleep deprivation or seven days of sleep restriction to four hours per night reduce performance the same as a blood alcohol level of 1‰ (Fig. 2) [6]. Driving at night, in the early afternoon and on weekends, and driving for long periods without adequate rest can pose an additional risk and should be avoided [1].

Diagnostic methods

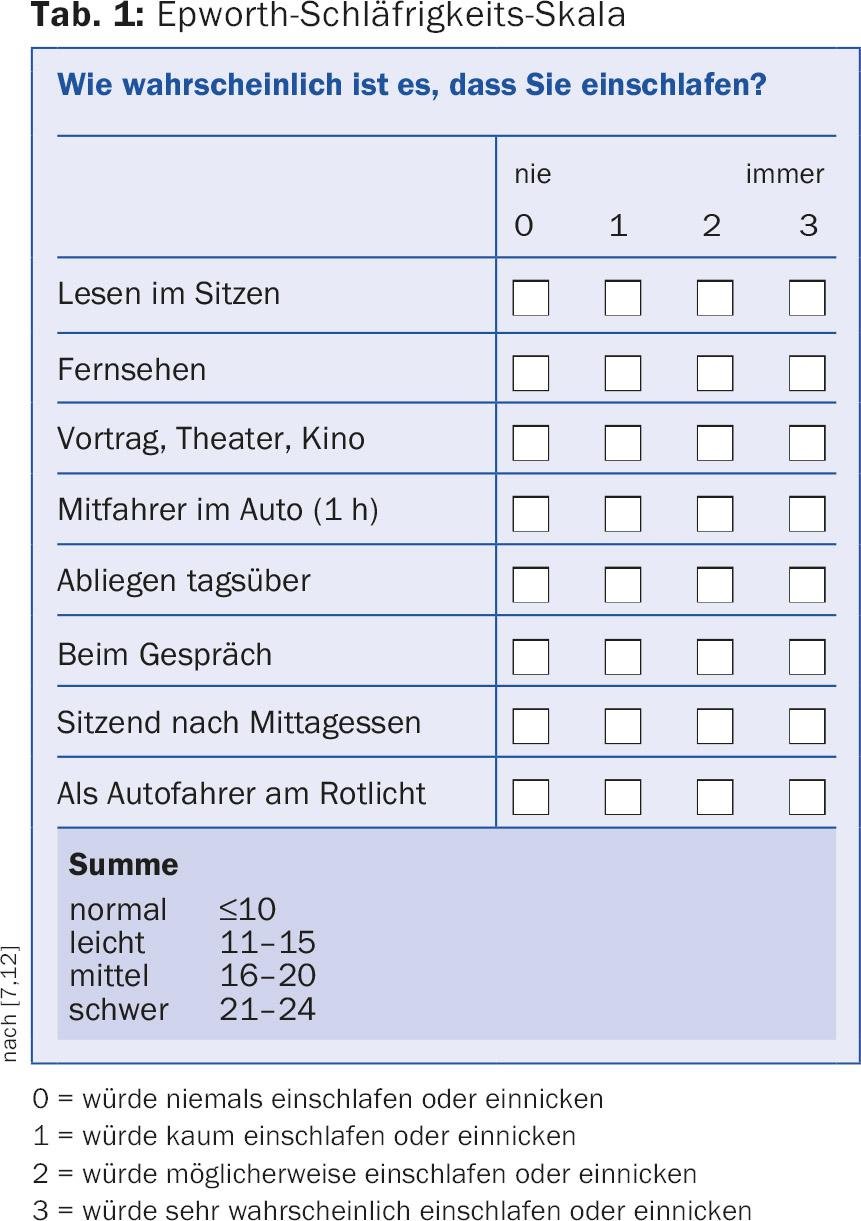

The medical history helps significantly to narrow down the various causes of daytime sleepiness. Subjective daytime sleepiness can be quantified using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (Table 1) [7]. A value >10 is considered abnormal. The score correlates with the frequency of traffic accidents suffered [1]. In professional drivers and also in patients in whom drowsiness has often developed insidiously over years, a value that is too low is usually given. Accordingly, the history of others is very important here [1]. Unreasonable drivers, professional drivers and PW drivers who have already suffered an accident due to microsleep should be referred to a sleep center. The ability to stay awake can be objectified and quantified using a Multiple Waking Test (MWT) or a driving simulator (Fig. 3) [1].

If there is evidence of sleep apnea syndrome, restless legs syndrome, narcolepsy, or parasomnias as the cause of daytime sleepiness, this can be confirmed using a sleep study, video polysomnography (Fig. 4). A subsequent multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) can provide evidence for the presence of narcolepsy or idiopathic hypersomnia and distinguishes an increased tendency to fall asleep from daytime sleepiness or lack of energy, which is common in psychiatric patients [1]. Hypothyroidism, anemia, metabolic derangement, electrolyte disturbances, and inflammatory diseases should be excluded.

The sleep apnea syndrome

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is a common condition and affects 5-19% of all adults. It occurs more frequently in overweight people and men. Patients with untreated obstructive sleep apnea syndrome have an increased risk of suffering from cardiovascular disease. Daytime sleepiness can take on considerable proportions. The following questions have proven useful for sleep apnea screening [1]:

- Do you snore so loudly that others are disturbed?

- Do pauses in breathing occur during sleep?

- Is snoring/breathing worse in supine position?

- Is snoring/breathing worse after drinking alcohol?

- Are you overweight?

For obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, patients are recommended continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy during the night. CPAP therapy generates a slight positive pressure via a continuous supply of air to the airways, which counteracts respiratory collapse (Fig. 5) . Most users report better sleep quality, improved concentration and less daytime sleepiness. The risk of accidents can be significantly reduced or even normalized [1]. It is always recommended to objectify daytime sleepiness by means of MWT for professional drivers under CPAP therapy or if episodes of microsleep have already occurred.

RLS, insomnia, nocturnal epilepsies or parasomnias.

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is characterized by unpleasant sensations in the extremities accompanied by motor restlessness. This occurs mainly in the evening and leads to difficulties falling asleep and staying asleep. The frequent occurrence of periodic limb movements, which lead to awakening reactions during sleep, as demonstrated by video-polysomnography, supports the diagnosis. In addition to measures such as exercise and cold-warm showers, dopamine agonists or alpha-2-delta calcium channel ligands can be used.

Insomnia usually results in daytime sleepiness or lack of energy and rarely daytime sleepiness [1]. Patients with insomnia are more comparable to individuals after excessive coffee consumption. Often there is an underlying depression or anxiety disorder. Psychophysiological insomnia, a “learned insomnia,” is also frequently found. For clarification, it is recommended to perform a wrist motion measurement (actigraphy) over 7-14 days. The sleep-wake rhythm is registered in the process. In rare cases, epileptic seizures or parasomnias such as sleepwalking can cause daytime sleepiness.

Narcolepsy and other hypersomnias

Hypersomnia is defined by excessive daytime sleepiness manifested by prolonged nighttime sleep or daytime sleep attacks. After exclusion of socially related or internal causes and unremarkable video-polysomnography, a group of primary hypersomnias remains, e.g. narcolepsy [1]. This is characterized by irresistible attacks of falling asleep, daytime sleepiness, sleep disturbances and cataplexies, in which – triggered by strong emotions – loss of muscle tension can occur. In addition, “non-organic hypersomnia” is frequently found in depression or anxiety disorder [1]. In order to diagnose these rare and mostly complex clinical pictures, a detailed sleep medical clarification in a center is recommended.

Drugs and medication

Unfortunately, according to Swiss statistics, every fourth person has driven a car at least once within the last year after drinking at least two glasses of alcohol one or two hours before. In 10% of all serious traffic accidents, excessive alcohol consumption is suspected as the trigger [1]. Even low blood alcohol levels can lead to significant impairment of concentration, especially in combination with sleep deprivation and night driving [8]. In addition to sleep medications and sedating drugs, β-blockers, antihistamines, antidepressants, antiepileptics, opiates, and many other medications also lead to increased daytime sleepiness.

Measures

In addition to clarification and therapy, the treating physician is obliged to carefully educate the patient with daytime sleepiness. For legal reasons, this should be recorded in the medical record on the occasion of the first consultation [1]. The primary responsibility for the safe operation of a motor vehicle rests with the driver. When drowsiness is detected, the lane should be left immediately. Whether this responsibility can be assigned to a patient must be decided clinically.

Driving a motor vehicle while drowsy is a negligent act and is interpreted as a serious traffic violation. An accident caused by falling asleep at the wheel is to be considered analogous to an accident under the influence of alcohol and, in addition to a fine, can lead to the withdrawal of identification or to claims for compensation by the insurance companies. A drowsy patient should refrain from driving until the cause is determined and successfully treated [9]. In the case of undiscerning patients, the physician in Switzerland has the possibility, although not the obligation, to report such a driver to the licensing authority (Road Traffic Act [SVG] Art. 14) [1].

It is unfortunate that there is a lack of guidelines that police officers and physicians can use to assess fitness to drive in daytime sleepiness. For physicians, in the absence of scientific evidence, there are at least “recommendations for assessing fitness to drive in daytime sleepiness” [10]. Traffic police need to be better trained to correctly identify drowsiness as a cause of an accident. Improved information exchange and close cooperation between police, authorities and physicians would be desirable.

Literature:

- Mathis J, Schreier D: Daytime sleepiness and driving behaviour. Therapeutic Review 2014; 71: 679-686.

- Schreier DR, Roth C, Mathis J: Subjective perception of sleepiness in a driving simulator is different from that in the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test. Sleep medicine 2015; 16: 994-998.

- Horne J, Reyner L: Vehicle accidents related to sleep: a review. Occupational and environmental medicine 1999; 56: 289-294.

- Reyner LA, Horne JA: Falling asleep while driving: are drivers aware of prior sleepiness? International journal of legal medicine 1998; 111: 120-123.

- Schwarz JF, et al: In-car countermeasures open window and music revisited on the real road: popular but hardly effective against driver sleepiness. Journal of sleep research 2012; 21: 595-599.

- Dawson D, Reid K: Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment. Nature 1997; 388: 235.

- Johns MW: A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991; 14: 540-545.

- Gengo FM, et al: The pharmacodynamics of ethanol: effects on performance and judgment. Journal of clinical pharmacology 1990; 30: 748-754.

- Pakola SJ, Dinges DF, Pack AI: Review of regulations and guidelines for commercial and noncommercial drivers with sleep apnea and narcolepsy. Sleep 1995; 18: 787-796.

- Mathis J, Kehrer P, Wirtz G: Fitness to drive in drowsiness: recommendations for physicians in the management of patients with increased drowsiness. Switzerland Med Forum 2007: 328-332.

- Reyner LA, Horne JA: Suppression of sleepiness in drivers: combination of caffeine with a short nap. Psychophysiology 1997 Nov; 34(6): 721-725.

- Bloch KE, et al: German version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Respiration 1999; 66(5): 440-447.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(1): 12-16