House dust mite (HDM) is a clinically and epidemiologically important allergen in allergic asthma. Allergens can be used for treatment in sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT). Thus, the need for ICS is reduced.

The allergenicity of HDM is associated not only with the mites or their feces, in which the main allergens are excreted, but also with ligands from mite-associated bacteria and mold products. Preventive approaches – also due to the necessity that patients often do not even present to the doctor in primary prevention – are little pursued. They are used even less frequently in the therapy of patients with house dust mite allergy than for grass pollen allergy.

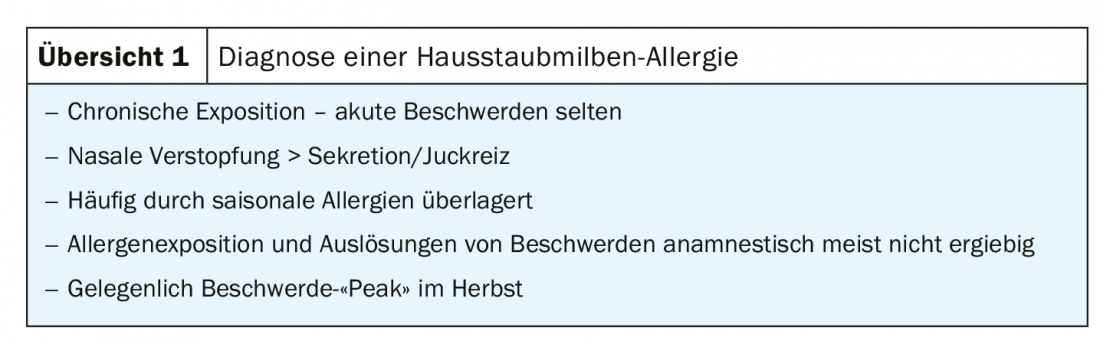

House dust mite sensitization is less adherent – unlike seasonal allergens, which are classically associated with itching, runny nose or airway obstruction acutely due to allergen contact and discomfort in the context of early allergic reaction. Clinically, patients have a chronic, often subclinical, influx of allergens, mostly because they are exposed to them at night in bed, and therefore tend to have chronic symptoms such as nasal congestion and chronic airway obstruction (review 1).

For the treatment of allergic asthma, sublingual immunotherapy for house dust mites (HDM-SLIT) may use allergens to reduce the need for inhaled glucocorticosteroids (ICS). For example, in a 2014 phase II study [1], patients (n=604) with HDM-related allergic asthma were given different doses of house dust mite sublingual therapy over a 40-week period and the steroid dose was reduced. It could be shown that the reduction of ICS under verum therapy with the house dust mite allergen was still 81 µg (p=0.004) on average. “That doesn’t sound like much at first,” explained Professor Johann-Christian Virchow, MD, Department of Pneumology/Internal Intensive Care Medicine, Center for Internal Medicine, Clinic I, Rostock University Hospital. “However, if we then look at the patients who had severe asthma and inhaled 400-800 μg of budesonide for their asthma control, the reduction was significantly more pronounced in this group with 327 µg of inhaled steroid (p=0.0001).” However, the number of patients here was still only 108.

Immunotherapy so far rather a means of last choice

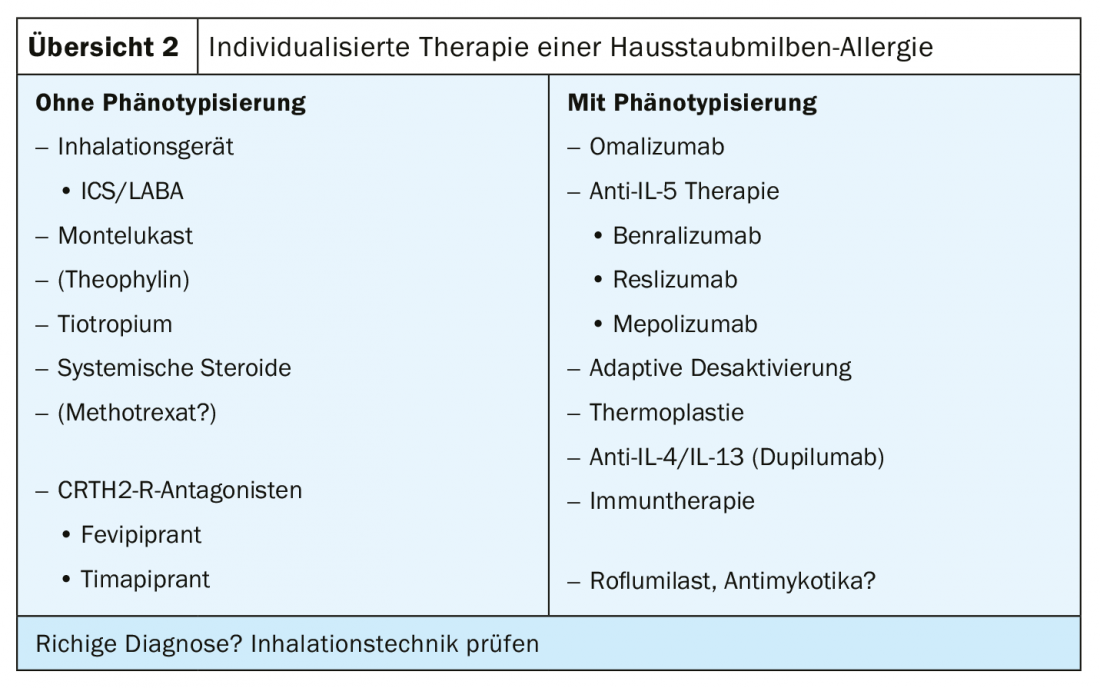

In individualized therapy of allergic asthma, patients have been selected according to whether or not phenotyping has occurred. Those without phenotyping were given whatever worked for all forms of asthma, i.e. ICS/LABA, montelukast, tiotropium or systemic steroids. In contrast, in those who were phenotyped, it was possible to target different medications in the sense of precision medicine, starting with omalizumab and including anti-IL-5 therapy and the newly approved anti-IL-4/IL-13 antibody dupilumab. Immunotherapy, on the other hand, was always very low down in the previous guidelines, as a last resort, so to speak. There were good reasons for this, such as the relatively small number of case series and the fact that the evidence was mainly drawn from meta-analyses. It is only in the current recommendations of GINA (Global Initiative for Asthma) that it says: “Consider the additional use of SLIT in adult patients with house dust mite allergy with allergic rhinitis who have exacerbations despite ICS.” A prerequisite for the recommendation was that FEV1 >70% of predicted lung function is (Overview 2).

Immunotherapy can reduce the inhaled steroid dose, so the next step would be that it should be able to prevent the occurrence of exacerbations when ICS is reduced by taking over a partial effect of the inhaled glucocorticosteroid. This has been tried with the house dust mite or HDM-SLIT tablet, which contains standardized the major allergens of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (DPT) and Dermatophagoides farinae (DF), as well as other allergens that are not standardized. In the prospective, randomized, double-blind MITRA-04 study conducted by Prof. Virchow and his colleagues in Rostock, the effect of the tablet, which is placed under the tongue and allowed to dissolve there, was investigated in a dose-dependent manner in comparison with placebo in 834 patients.

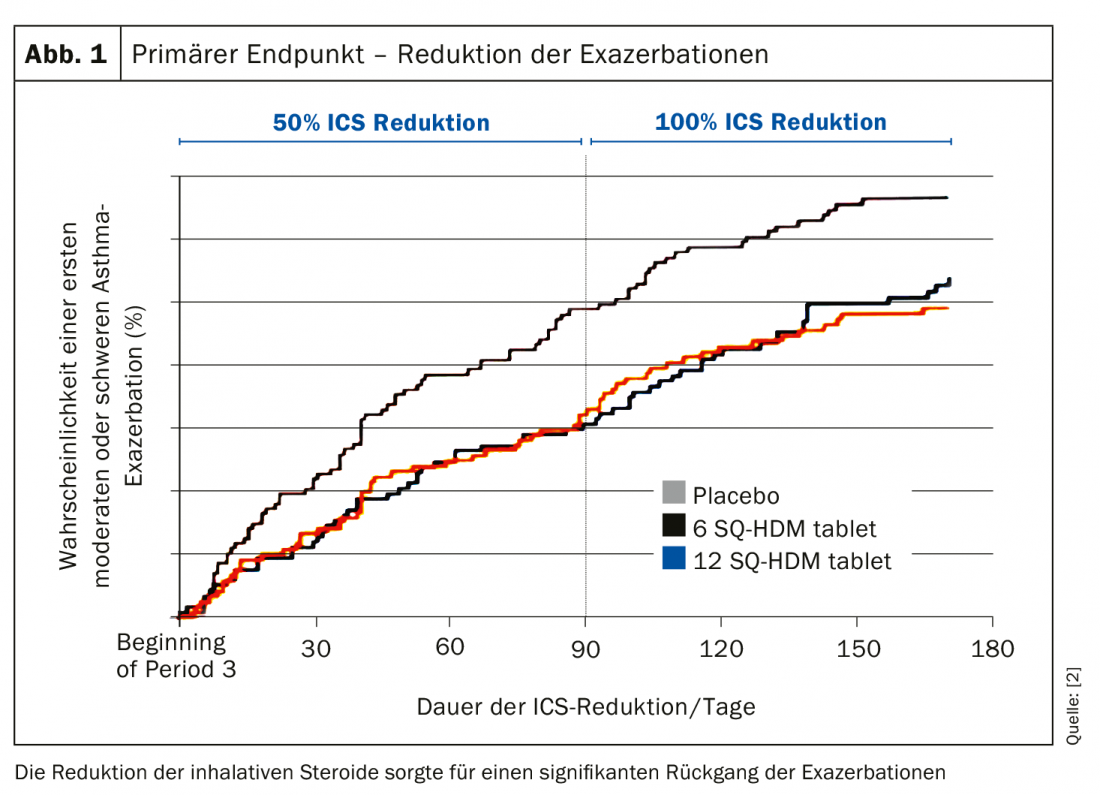

As a proof of concept, in a maximum of 12 months of therapy, the ICS dose was initially reduced by 50%, and if patients continued to be stable, to 100%, i.e. discontinued. The idea behind this was to provoke exacerbations in order to test whether immunotherapy could partially replace the effect of ICS. Moderate-severe exacerbations were defined classically according to pulmonary function criteria, i.e., if FEV1 or PEF decreased by 20% for two consecutive mornings/evenings, if the requirement of SABA increased by at least four strokes/day from baseline for two consecutive days, if nocturnal awakening or an increase in symptom score by ≥0.75 from baseline began for two consecutive days, or if one had to visit an emergency department or study center had to be visited without a change in systemic corticosteroid dose. Severe exacerbations were those for which systemic steroids were used for at least three days or for which patients required hospitalization for asthma and received glucocorticosteroids for therapy.

Selection criteria were house dust mite-induced allergic asthma for at least one year, documented reversible airway obstruction, history of allergic rhinitis, and GINA guideline levels 2 to 4 steroid use (with ICS dosing between 400 and 1200 µg after switching to budesonide). In addition, the asthma control level at randomization had to correspond to “partially controlled,” with an ACQ(Asthma Control Questionaire) score of 1.0-1.5. Lung function had to be better than 70 percent of set point and there had to be a clinical diagnosis of house dust mite allergy.

Reduction of ICS ensures fewer exacerbations

Patients were 48% women with a mean age of 33 years who had had asthma for a mean of 13 years. 66% were sensitized to other allergies. 72% had partially controlled asthma and 28% even had uncontrolled asthma after GINA. The result was as clear as it was astonishing: the 50% reduction in inhaled steroids compared to placebo provided a significant decrease in exacerbations in the verum group. This was maintained even when steroids were reduced by 100% – again, there was a 30-34% reduction in exacerbation frequency (Fig. 1). “So we can say that the effect of inhaled steroids is at least partially maintained by allergen immunotherapy sublingually at both doses,” Prof. Virchow concluded. The picture was the same for the secondary endpoints. Symptom exacerbation, increase in the use of short-acting beta agonists, worsening of lung function, or even the severity of exacerbations followed the same pattern. Only in severe exacerbations was the result not statistically significant.

Thus, the results of MITRA-04 demonstrated that SLIT can be successfully used as an add-on therapy in uncontrolled asthmatics with house dust mite allergy. In both SLIT groups, the risk of experiencing moderate or severe asthma exacerbations was significantly reduced by 28% compared with placebo. Favorable effects of SLIT were also noted on symptomatology, SABA use, and pulmonary function. The GINA guideline from 2013 still stated that one had to have a single, well-defined clinically relevant allergen to consider immunotherapy, the options for which were limited anyway. He also said that the overall effects of sublingual immunotherapy were rather modest. According to Prof. Virchow, this view probably needs to be revised. The patients in the MITRA-04 study had 66% other sensitization as described, so one does not have to be monovalently sensitized here. Moreover, the results did not depend on whether they were sensitized to the mite alone or had other sensitizations; the effects were identical in the respective groups.

Changes in the next guideline

“After GINA, the lung function had to be >70%, but we did not find that compared with the patients who had uncontrolled asthma, the adverse event frequency was different.” Rather, the opposite was observed: In those with uncontrolled asthma, side effects were actually numerically a little lower. The side effects essentially play out in the mouth; oral pruritus had the highest incidence. In contrast, anaphylactic reactions or severe reactions that would have required drug intervention did not occur. In most cases, the accompanying symptoms subsided after two weeks at the latest. GINA also maintains that one must have exacerbations to benefit from therapy. “It wasn’t clear to us how that got in there,” the expert says. “And the scientific author of the guideline was also surprised when asked. It won’t be in the next guideline that way.”

When asked which patients are candidates for targeted intervention, Prof. Virchow named three groups:

- Patients who have sensitization to dust mite allergen. They do not necessarily have to be monovalently sensitized. Their detection remains a clinical challenge.

- Patients with allergic rhinitis, manifested primarily by nasal congestion and chronic symptoms. Also often confused with nasal polyps.

- Patients with allergic asthma, also with chronic symptoms, possibly late summer exacerbation, making differential diagnosis to spore flight or herb pollen asthma difficult. They do not necessarily have to be mono-sensitized or asymptomatic on asthma therapy, because even the uncontrolled patients benefit without a significant increase in side effects. They do not necessarily have to be well controlled and exacerbations are not a prerequisite.

Summary

- With regard to precision medicine in asthma, allergen immunotherapy can be used to

- Reduce the frequency of exacerbations in patients with asthma and rhinitis

- HDM-AIT (SLIT) can at least partially replace the anti-inflammatory (controller) effect of ICS

- Immunotherapy can improve asthma control

- HDM-SLIT may be considered in phenotype-specific therapy of allergic asthma

Source: 60th Congress of the DGP

Literature:

- Mosbech H, et al: JACI 2014; 134: 558-575.

- Virchow JC, et al: JAMA 2016; 315: 1715-1725.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2019; 1(1): 20-22 (published 6/3/19, ahead of print).