ADHD does not grow out during adolescence, but persists to a large extent into adulthood. However, the symptoms change, so that many sufferers remain undetected and therefore untreated. An effective treatment regimen is multimodal.

Contrary to popular belief, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) does not grow during adolescence. Instead, the revised doctrine assumes that the disease manifests in childhood but remains symptomatic in the majority of affected individuals in adulthood due to a high tendency to become chronic, and that some of them also require clinical treatment. In childhood and adolescence, the prevalence is between 3 and 5%; in adults, 1-4% of affected individuals are thought to be affected [1–4a].

Symptom change masks disease

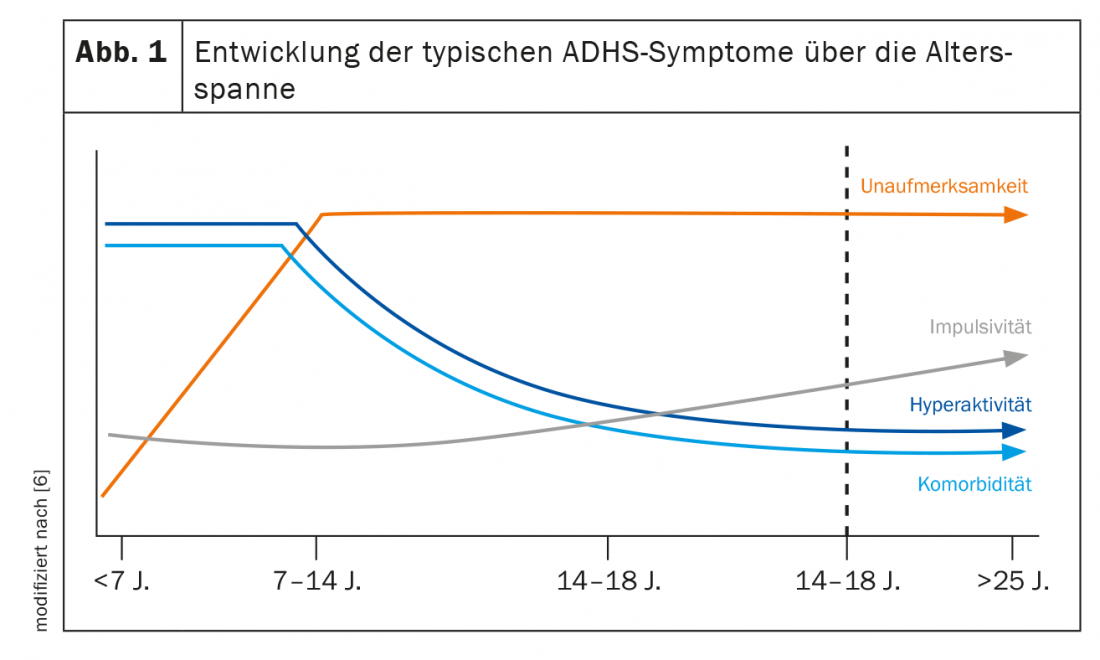

However, adult ADHD is often not recognized. Experts estimate that less than 20% of patients are diagnosed [5]. This is predominantly due to two main factors. On the one hand, there is an age-related change in the leading symptom triad of attention deficit disorder, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (Fig. 1) [6]:

- While motor hyperactivity is the main focus of attention in childhood, this picture often shifts to inner restlessness as the child grows up.

- Attention deficit persists. It persists in 80% of those affected. Difficulties in this area then become apparent, for example, in the organization of work.

- Impulsivity decreases in 40% of patients, but often still manifests itself, for example, in inappropriate remarks or when participating in traffic.

- Disorganization and emotional dysregulation often increase in severity as additional symptoms in early adulthood.

Thus, hyperactivity that is clinically conspicuous in childhood is usually more inconspicuous or modified in adults, for example, as nervous foot bobbing or finger drumming during periods of forced inactivity. Many affected persons experience situations such as long-distance flights, visits to the cinema/theaters with a high degree of inner tension due to the restriction of movement and try to avoid them in everyday life. According to clinical observations, a strong urge to exercise is often expressed in extreme endurance sports (e.g., marathon running). It is not uncommon to have a propensity for high-risk sports.

Focus on increased accident risk

This fact gains significance from the fact that adult ADHD is associated with a 143% increased risk of accidents [7]. The probability of a car accident alone is three times higher [8]. Estimates lead to the conclusion that approximately 22% of all car accidents could have been prevented if those affected had received adequate treatment, including pharmacological treatment [9]. In addition to attention deficit and distractibility, accident-causing risk factors include slower reaction time and overestimation of driving skills due to impaired self-awareness [10]. One study examined the prevalence of adult ADHD in a population of accident victims at two trauma hospitals [11]. The results show that among accident victims, affected individuals with AHDS were significantly overrepresented. However, only 17% had already been diagnosed with the disease. Of these, only one-third received adequate pharmacological treatment.

When the attention is missing

Impairments of attention and concentration caused by disorders often become apparent when affected adults describe problems in their (professional) everyday life. Due to a high level of distractibility and openness to stimuli, there may be difficulties with the organization of processes and with the planning and structuring of the work to be done. Accordingly, the overall work behavior is not infrequently characterized by inefficiency and poor time management. Problems with concentration can provoke errors at work and generally impair work performance, for example, because instructions or texts have to be read several times or mind wandering and circling of thoughts occur during lectures. A lack of impulse control can also cause problems for those affected at work, in relationships, in the family and in their social environment. Typical behavior here is unasked-for intrusion into conversations and a tendency to take unthought-out, spontaneous actions [12].

Comorbidities often dominate

Another reason adult ADHD is often overlooked is because of the comorbidities that may be present. ADHD rarely occurs as an isolated disorder in adult psychiatric practice. In about four out of five affected persons, the clinical picture is completely or partially overlaid by at least one other mental illness [13]. That comorbidities are the rule rather than the exception in adult ADHD patients was found in a multicenter observational study of adults: At the time of ADHD diagnosis, psychiatric comorbidity was found to be 66.2%, with more males affected [14]. The most common comorbidities of ADHD in adults include:

- Addictive disorders

- Anxiety disorders

- affective disorders.

The exact etiologic relationship between ADHD and these comorbidities is unknown. However, ADHD as a pediatric disorder is usually thought to manifest temporally before the comorbid disorder. Psychological comorbidity could then develop secondarily, for example as a result of long-term negative experiences and frustrations co-induced by ADHD. Clinically, it is relevant that these secondary disorders can develop dynamics during the course and dominate the overall clinical picture [15].

Few patients with depression, bipolar disorder, or anxiety disorder also receive a concurrent ADHD diagnosis. In most cases, although patients are treated, coexisting ADHD is sometimes overlooked. This may have a negative impact on the therapeutic success of the aforementioned comorbidities. Successful treatment of the underlying disease may help to improve comorbidities beyond improvement of core symptoms [16–18].

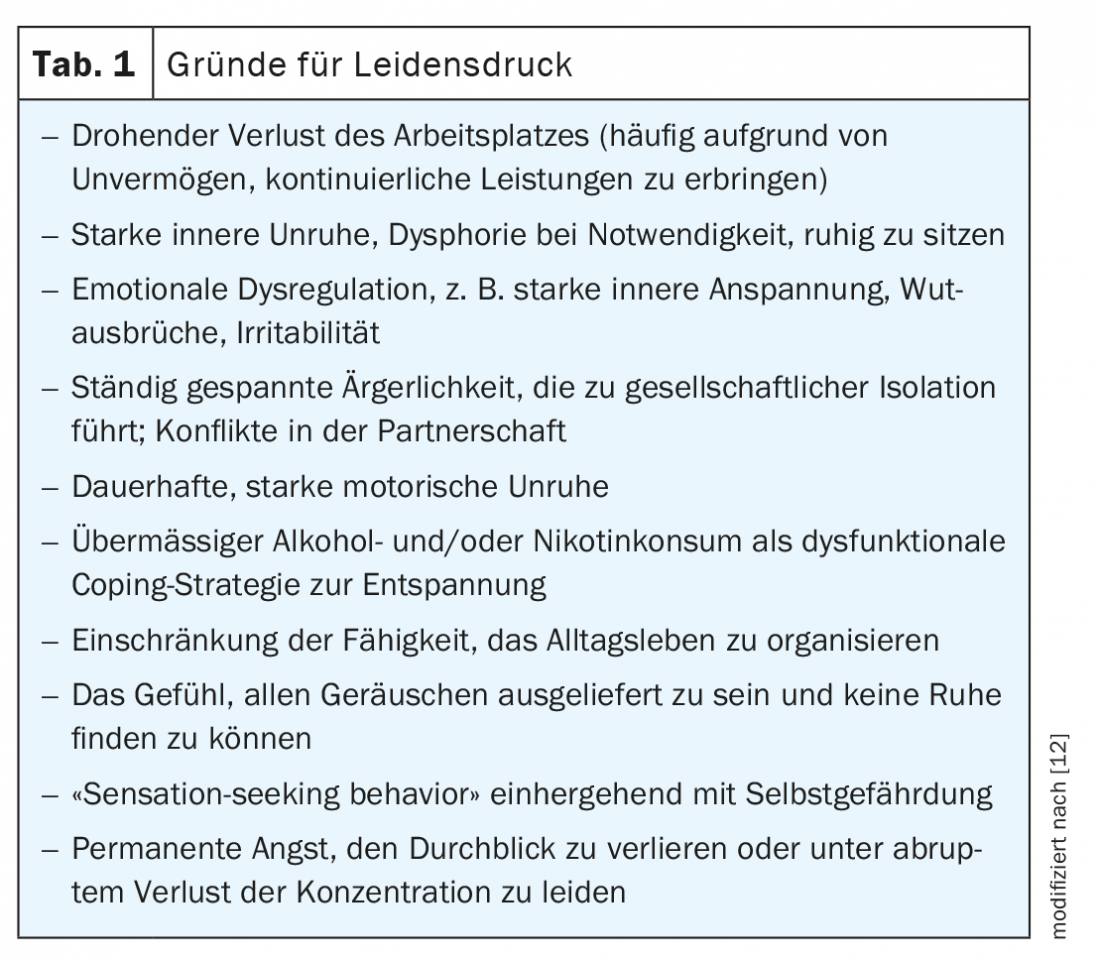

Multimodal treatment regimen indicated

Treatment should take into account both the ADHD core symptomatology and the presence of comorbid disorders and should therefore generally be multimodal, i.e., using the available therapy components of psychoeducation, psychotherapy, and pharmacotherapy (tab. 1). Within the framework of the multimodal therapy concept, non-drug measures such as education and psychoeducation are proposed as a basis at the beginning of therapy. In addition, psychotherapeutic interventions are recommended, especially for the self-esteem problems often present in affected individuals or other concomitant diseases [19]. Drug treatment may become necessary in order to create a neurobiological basis in this way, which enables patients to access further therapeutic measures such as behavioral therapy in the first place. The goal of all therapeutic interventions is to achieve the most comprehensive symptom remission and restoration of psychosocial functioning.

Address pharmacotherapy early

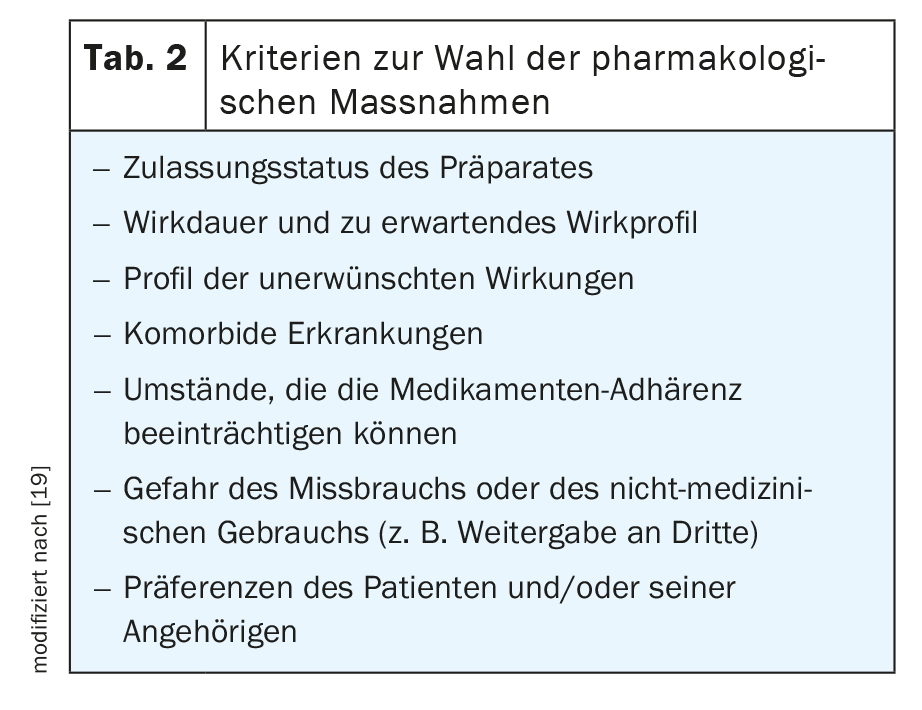

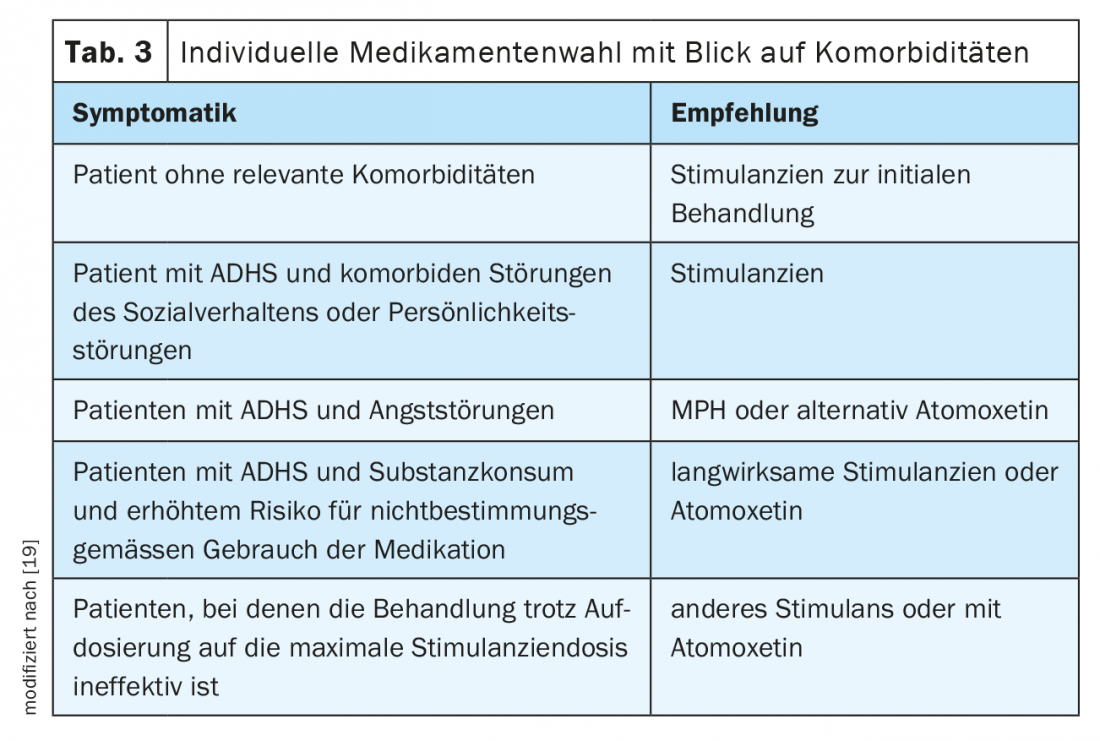

For a long time, there were no pharmacological treatment options approved for adults in many European countries. At least three preparations are now available, with the gold standard methylphenidate (MPH) and lisdexamphetamine (LDX) as stimulants and atomoxetine (ATX) as a non-stimulant. Which preparation is selected should be considered individually (Tab. 2, Tab. 3) .

According to studies, 75% of treated patients benefit from MPH therapy when a symptom reduction of at least 30% is used as a criterion for therapeutic success [20]. Several meta-analyses have demonstrated significant efficacy on core ADHD symptoms [21–23]. In addition, it leads to a reduction in emotional regulation disorder [24]. The stimulant inhibits the reuptake of dopamine and, to a lesser extent, norepinephrine from the synaptic cleft into the presynaptic neuron by inhibiting the corresponding monoamine transporters. This increases the transmitter concentration in the synaptic cleft and optimizes signal transmission.

The effect of LDX, on the other hand, is different. This prodrug is hydrolyzed into the active d-amphetamine in the cytosol of erythrocytes. D-amphetamine causes an increased release of dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain and inhibits their reuptake into the presynaptic neuron. In principle, the efficacy appears to be comparable to that of MPH with a slight tendency toward a higher effect size on core symptomatology [25,26].

The norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine inhibits the norepinephrine transporter. This increases the availability of norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft of the neuron. Its prescription is indicated primarily when stimulants are not effective or are not tolerated or rejected by the patient. However, the efficacy is lower than that of stimulants [27]. Other substances such as bupropion also appear to have efficacy but are not approved for the indication [27].

Adverse effects

Of course, side effects can occur with any pharmacological intervention. In general, however, stimulants in particular are well tolerated. Adverse drug reactions may occur, particularly at the beginning of therapy, but are usually mild to moderate and can be attributed to the mechanism of action. They are often dose-dependent and can be well controlled by individual titration. For example, decreased appetite, difficulty falling asleep, and headaches may be observed. An increase in pulse rate and blood pressure are also possible.

The non-stimulant atomoxetine is also well tolerated overall. Likewise, undesirable side effects occur predominantly in the first weeks of treatment and are rarely severe. In addition to headaches and decreased appetite, abdominal discomfort, nausea, and mood swings are possible.

In addition, attention should be paid to sexual dysfunction, erectile or ejaculatory dysfunction, and dysmenorrhea. In addition, suicidal ideation has been reported in patients younger than 30 years at the beginning of therapy. Since increases in heart rate and blood pressure can occur with both stimulants and atomoxetine, cardiovascular disease should be ruled out before initiating therapy. In addition, pulse, blood pressure and body weight should be determined and checked regularly during the course of treatment.

Therapy designed for the long term

In principle, the duration of drug treatment is based on the individual needs of the patient. Sometimes time-limited interventions may be appropriate, for example, when changes in life circumstances could lead to functional impairment. In general, however, the treatment should be set for the long term. Follow-up studies show that long-term therapy over several years leads to greater symptom reduction and improvement in daily functioning than short-term treatment [28].

In addition, the effectiveness of the preparations can also only be fully assessed after several weeks. Therefore, premature discontinuation of therapy should be avoided. Nevertheless, discontinuation attempts may always be scheduled to verify the persistence of the indication for pharmacotherapy.

Conclusion

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder persists into adulthood in 66% of those affected [29]. However, adult patients with ADHD are still too rarely diagnosed. A change in the typical core symptomatology of attention deficit disorder, hyperactivity and impulsivity, as well as comorbid conditions may mask the underlying disorder. Accordingly, adults with ADHD rarely receive effective therapy. But this can have serious consequences. Effective substances are available that achieve good results in addition to psychotherapy and psychoeducation. The drug of first choice is methylphenidate. Both core symptoms and emotional dysregulation can be effectively reduced with stimulants.

Take-Home Messages

- ADHD persists into adulthood at a rate of about 66%, but often goes undetected due to symptom change and emerging comorbidities.

- An effective treatment regimen is multimodal in structure and includes psychoeducation, psychotherapy, and pharmacotherapy.

- Methylphenidad is available as a 1st-line agent.

- Pharmacological treatment can improve both core symptomatology and emotional dysregulation.

Literature:

- Nyberg E, et al: ADHD in adults. HOGREVE 2013.

- Fayyad J, et al: Br J Psychiatry 2007; 190: 402-409.

- Rösler M, et al: Nervenarzt 2008; 3: 320-327.

- Barbaresi WJ, et al: Pediatrics 2013; 131: 637-644.

4a. Estevez N, Eich-Höchli D, Dey M, et al: (2014) Prevalence of and Associated Factors for Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Young Swiss Men. PLoS ONE 9(2): e89298. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089298. - Polyzoi M, et al: Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018; 14: 1149-1161.

- Ströhlein B, et al: NeuroTransmitter 2016; 27.

- Chien WC, et al: Res Dev Disabil 2017; 65: 57-73.

- Bron TI, et al: Accid Anal Prev 2018; 111: 338-344.

- Chang Z, et al: JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74: 597-603.

- Barkely RA: Psychiatr Clin North Am 2004; 27(2): 233-260.

- Kittel-Schneider S, et al: J Clin Med 2019; 8(10): 1643.

- Krause J, Krause KH: ADHD in adulthood. Schattauer Publishers 2014.

- Rösler M, Retz W: Psychotherapy 2008; 13(2): 175-183.

- Pineiro-Dieguez B, et al: J Atten Disord 2016; 20: 1066-1075.

- Barkley RA: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. A handbook for diagnosis and treatment, 3rd ed. Guilford, New York

- Adler L, et al: Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Abstract 119. 19th US Psychiatric & Mental Health Congress; November 2006; New Orleans, Louisiana.

- Rostain AL: Postgrad Med 2008, 120(3): 27-38.

- Torgersen T, et al: North J Psychiatry 2006; 60(1): 38-43.

- Association of the Scientific Medical Societies. S3 guideline: ADHD in childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Registration number 028-045. AWMF; 2017

- Retz W, Rösler M: Therapy resistance in the treatment of ADHD in adulthood. In: Schmaus M, Messer T: Therapy resistance in mental illness. Munich: Elsevier; 2009: 175-188.

- Faraone SV, et al: J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24: 24-29.

- Koesters M, et al: J Psychopharmacol 2009; 23: 733-744.

- Castells X, et al: CNS Drugs 2011; 25: 157-169.

- Retz W, et al: Exp Rev Neurother 2012; 12: 1241-1251.

- Mészáros A, et al: Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2009; 12: 1137-1147.

- Stuhec M, Lukić P, Locatelli I: Ann Pharmacother 2018; 53: 121-133.

- Cortese S, et al: Lancet Psychiatry 2018; 5: 727-738.

- Fredriksen M, et al: Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2013; 23: 508-527.

- Kooij, et al: BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10: 67.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2020; 18(6): 12-15.