Early detection is critical for treatment options of this multisystem disease with cutaneous involvement. Raynaud’s attacks are often in early stages and should always be further evaluated. In addition to medications, non-pharmacological methods are increasingly being used to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life. Autologous stem cell transplantation is one of the new systemic approaches currently being explored.

Systemic scleroderma (SSc) continues to be lethality-laden but, due to advances in understanding the pathogenesis of the disease and improved diagnosis and therapy, is increasingly losing the horror of yesteryear.

Improving prognosis through targeted organ-based therapies

Thus, the 10- and 20-year survival rates of affected individuals with cutaneous limited systemic scleroderma (lSSc) – which includes the so-called CREST syndrome, a term that has become dispensable – hardly differ today from comparative collectives without scleroderma [7,10]. And in cutaneous diffuse systemic scleroderma (dSSc), the early use of targeted organ-based therapies is increasingly succeeding in slowing down as well as partially arresting the course of the disease. Here, the still risky autologous stem cell transplantation of SSc is receiving increasing attention. Along with this positive development, the numerous individual, sometimes serious somatic and psychological burdens of the chronic multisystem disease scleroderma are becoming more of a focus of medical efforts. In addition to symptomatic drug therapy, non-drug treatments of specialized medicine (physiotherapy, occupational therapy, manual lymphatic drainage, connective tissue massage, speech therapy, reflexive breathing therapy, dermatological phototherapy, medical training therapy, psychology, nutritional medicine) also play an important role.

Complex etiopathogenesis not yet fully elucidated

It is still not clear how the various immune mechanisms, vascular changes, and overproduction of collagenous connective tissue are related in systemic scleroderma (SSc). Also, the question of whether SSc is an autoimmune disease, i.e., whether aberrant immune responses are at the origin of the disease, or whether it is primarily a vasculopathy with subsequent inflammation and aberrant immune responses, has not been conclusively resolved. Other experts consider the main disorder of SSc to be dysregulation of connective tissue metabolism, analogous to impaired wound healing, e.g., as a result of trauma [2].

Successes of current therapy concern, on the one hand, circulatory disorders of scleroderma and its complications: secondary Raynaud phenomenon, digital ulcerations, pulmonary arterial hypertension, acute renal crisis; on the other hand, sclerosis of the skin and pulmonary fibrosis. The early diagnosis of the various organ complications and their early therapy are of key importance in this context. There may be a “window of opportunity” in the near future [5] that, if recognized and exploited in time, may help to halt the further development of scleroderma.

Good Clinical Practise recommendations

The 2013 reformulated ACR-EULAR classification criteria for systemic scleroderma are distinguished from the previously valid 1980 ACR classification criteria by the fact that Raynaud phenomenon, telangiectasia, and capillary microscopic changes of SSc are now also taken into account, as well as swelling of the fingers (so-called puffy hands), the specific antibody profile, and pulmonary arterial hypertension. This allows for better detection of early stages of the disease as well as affected individuals with limited SSc [1].

Importantly, in adults, even the first occurrence of a Raynaud’s attack leads to the determination of scleroderma-specific antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in serum and capillary microscopic examination of finger capillaries (clarifying the question of a scleroderma-typical pattern of damage) in order to detect incipient systemic scleroderma early enough. This is especially true for asymmetric Raynaud’s attacks (affecting only individual fingers) and when initial swelling of the fingers also occurs. The high sensitivity of these simple diagnostic measures has great significance for the early diagnosis of systemic scleroderma: thus, it is known that half of all damage to internal organs can be detected within 2 years of the first Raynaud’s attack [6]. Since early detection of SSc is essentially achieved via the skin and skin-related vessels, and changes in the skin are also of great importance for the overall morbidity of scleroderma in the further course, dermatologists as experts of the skin organ should continue to keep an active eye on and accompany this complex disease.

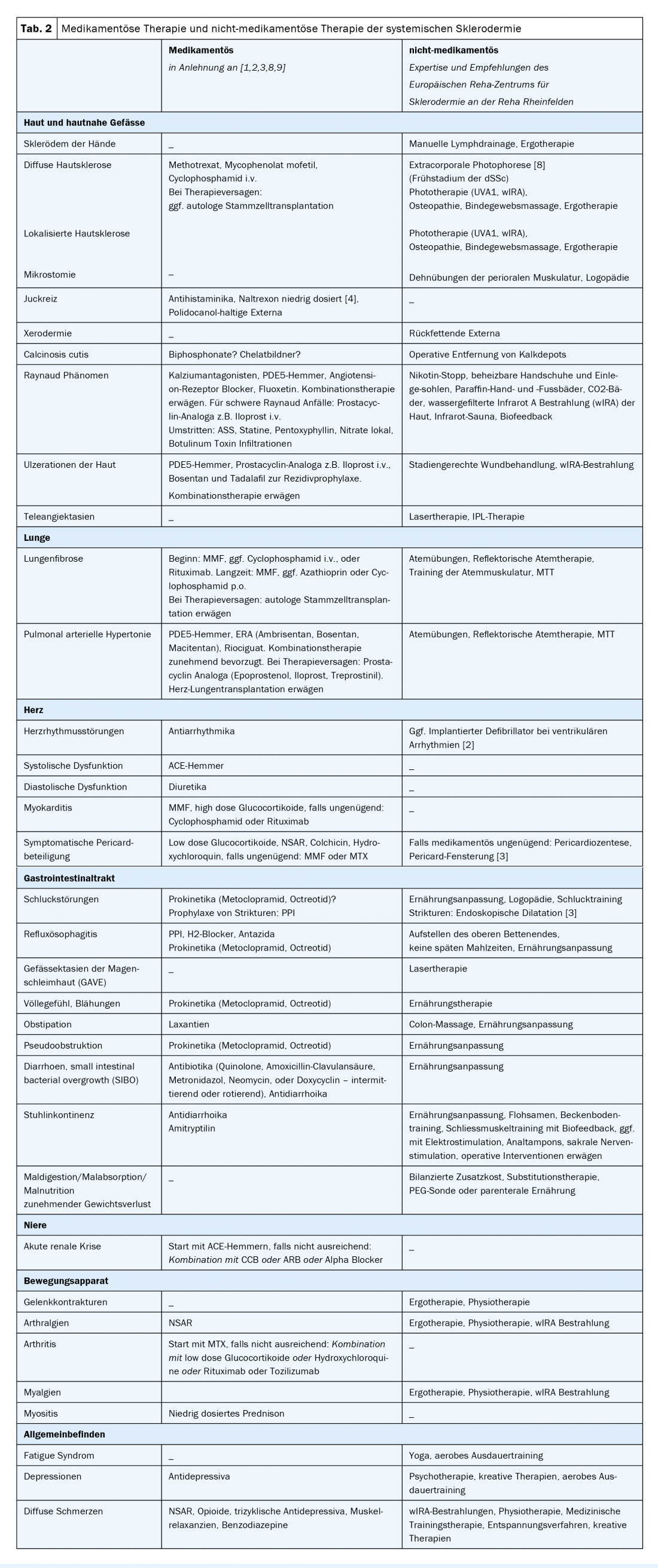

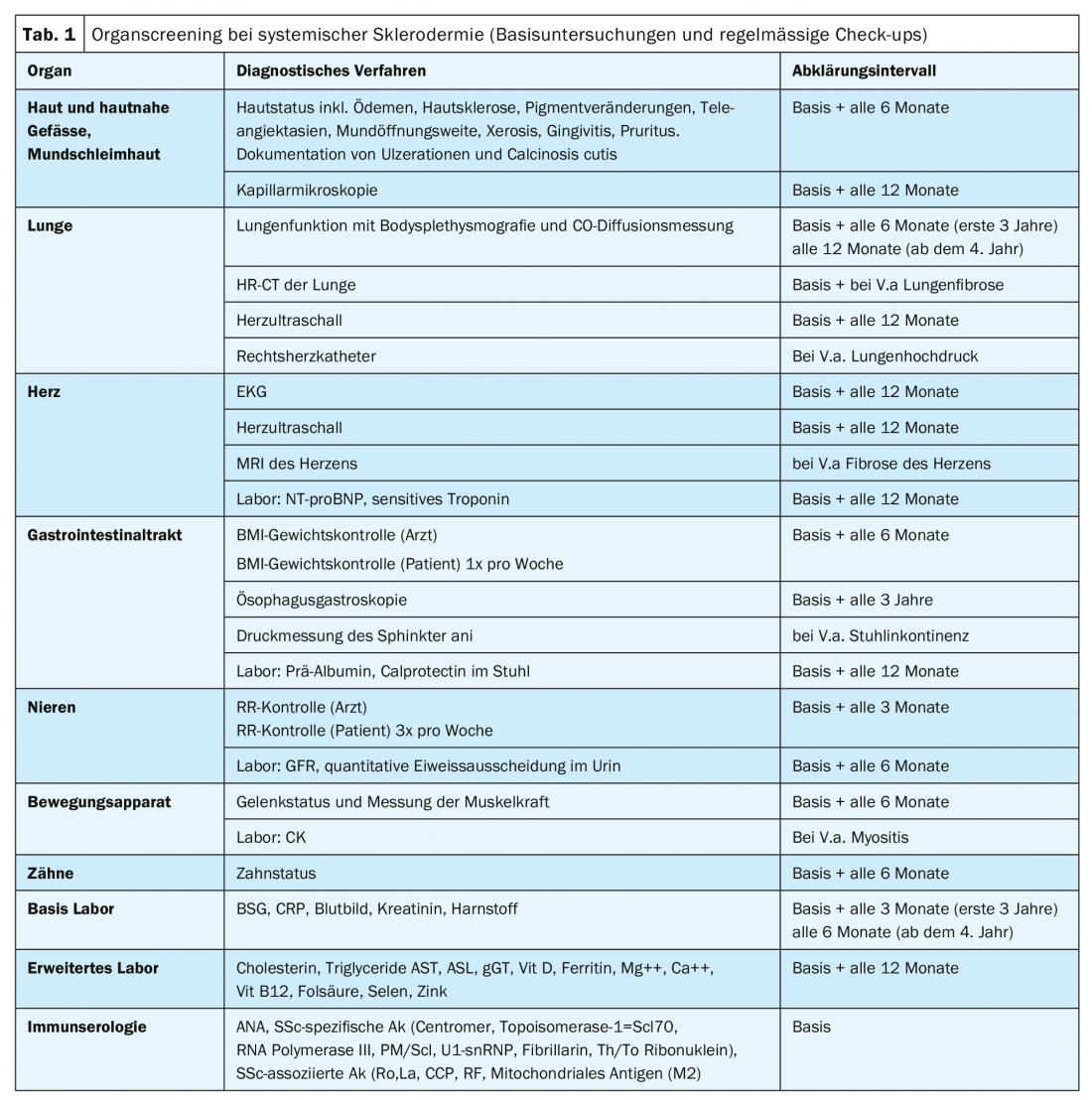

Recommendations for organ screening in SSc (baseline and follow-up) are summarized in Table 1 . Current recommendations for organ-related drug therapies of SSc according to studies (if available) or according to agreement/recommendations of international expert panels supplemented by suggestions for non-drug therapy of SSc, which essentially reflect the expertise of the European Scleroderma Rehabilitation Center of Reha Rheinfelden, can be seen in Table 2 .

Take-Home Messages

- Advances in diagnostic and therapeutic methods allow the progression of the disease to be slowed down and life expectancy to be increased. Careful diagnostic clarification and early detection are of crucial importance to optimally adapt therapy to the symptoms and should be repeated at regular intervals.

- The primary goal of organ-related drug therapies is to restore the functionality of the organs impaired by the multisystem disease. In addition to drug approaches, non-pharmacological methods are increasingly used to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

- Regarding the pathomechanisms of systemic scleroderma, there are still many open questions and new systemic therapy options (e.g. autologous stem cell transplantation) are still in the validation phase.

Literature:

- Allanore Y, et al: Systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015 Apr 23; 1: 15002. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.2.

- Denton C, Khanna D: Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2017; 390: 1685-1698.

- Fernández-Codina A, et al: Treatment algorithms for systemic sclerosis according to experts. Arthritis & Rheumatology 2018; 70: 1820-1828.

- Frech T, et al: Low-dose naltrexone for pruritus in systemic sclerosis. Int J Rheumatol 2011: 804296. published online 2011 Sep 12. doi: 10.1155/2011/804296

- Guiducci S, Bellando-Randone S, Matucci-Cerinic M: A new way of thinking about systemic sclerosis: the opportunity for a very early diagnosis. Isr Med Assoc J 2016; 18: 141-143.

- Jaeger VK, et al: Incidences and risk factors of organ manifestations in the early course of systemic sclerosis: a longitudinal EUSTAR study. PLos One 2016; 11: e0163894: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163894. eCollection 2016.

- Kennedy N, Walker J, Hakendorf P, Roberts-Thomson P: Improving life expectancy of patients with scleroderma: results from the South Australian Scleroderma Register. Intern Med J 2018; 48: 951-956.

- Knobler R, et al: European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, Part 1: localized scleroderma, systemic sclerosis and overlap syndroms. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31(9): 1401-1424.

- Kowal-Bielecka O, et al: Update of EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(8): 1327-1339.

- Simeon-Aznar CP, et al: Registry of the Spanish Network for systemic sclerosis: survival, prognostic factors, and causes of death. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015 Oct; 94(43): e1728. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001728.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2019; 29(3): 19-23