The genesis of rheumatoid polyarthritis (RA) is still largely unclear. However, with the introduction of the new biologicals – after decades of immunological research – revolutionary new treatment strategies for this previously only incompletely treatable disease have finally emerged.

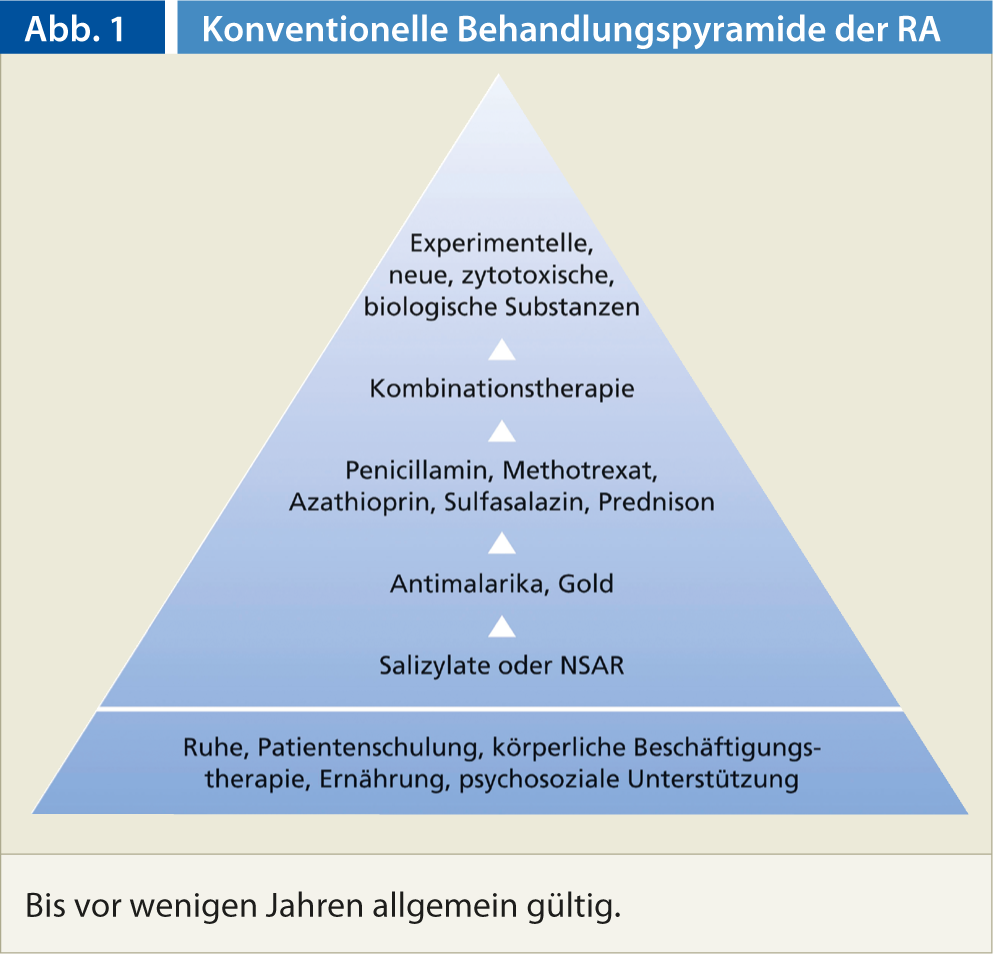

Drug treatment of rheumatoid arthritis to date has been based on the conventional treatment pyramid (Fig. 1). The pyramid model is based on the one hand on the risk-benefit concept and on the other hand on the assumption that the prognosis of RA is generally favorable. The previous treatment pyramid has now been changed so that therapy with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologicals begins much earlier.

The reasons for this are manifold: For one thing, rheumatoid arthritis is not a benign disease. In addition, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are not harmless; their gastrointestinal toxicity and other side effects cause considerable morbidity and mortality. It is also important to keep in mind that basic therapeutics are no more toxic than NSAIDs in skilled hands. Last but not least, with the early use of biologicals, aggressive forms of rheumatoid arthritis can be addressed at an early stage, the disease can be significantly influenced and in some cases even put into remission.

Disease-modifying basic therapeutics (DMARDs)

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)(Table 1) are used for clinically and humorally active polyarthritis, long before biological changes have occurred. This is especially true as soon as the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis is confirmed. Currently, methotrexate is the first-choice basic therapeutic agent, which has completely replaced gold, which used to be the primary agent. Methotrexate is no more toxic than NSAIDs or corticosteroids in skilled hands. Another advantage of this drug is its range of application (per os, i.v., i.m., s.c., as a pre-filled syringe for self-injection).

Current biologicals

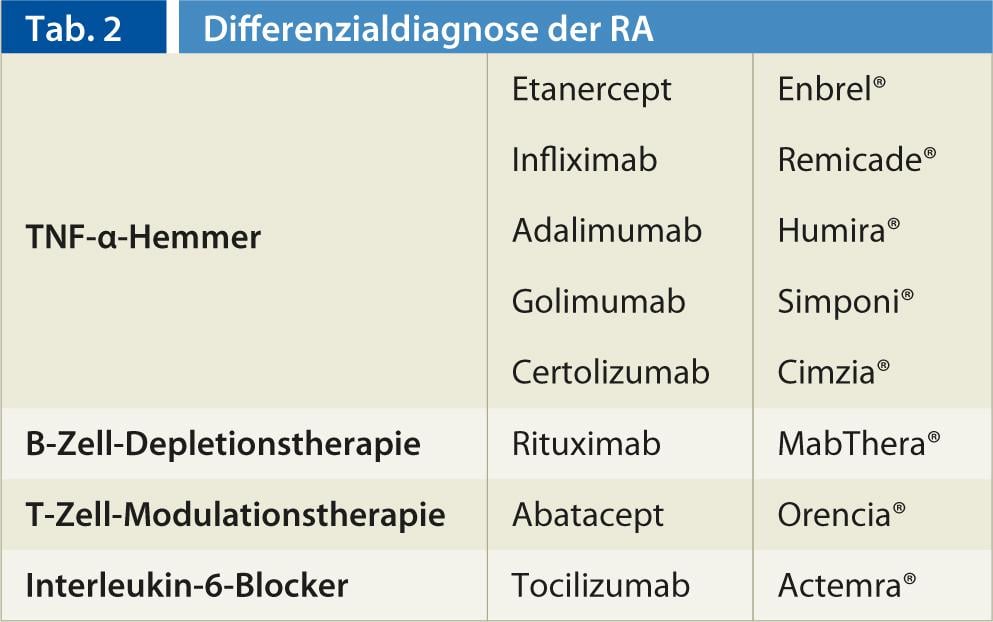

An overview of biologicals can be found in Table 2.

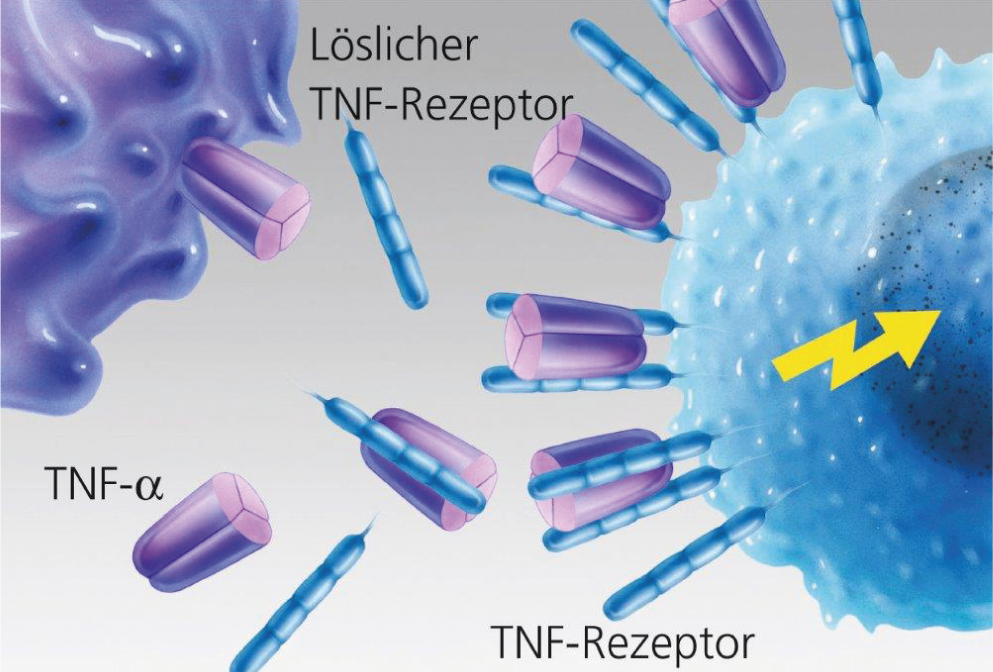

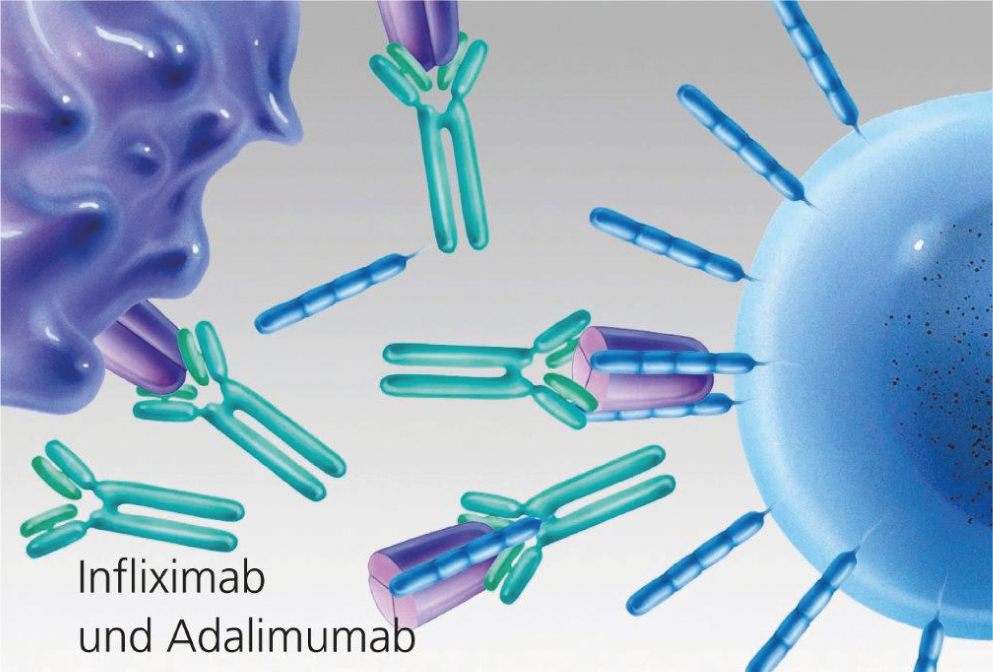

TNF-α inhibitors (Figs. 2, 3): In 1998, a first tumor necrosis factor-α antagonist (TNF-α inhibitor) was registered as a drug. Currently, the active ingredients Etanercept (Enbrel®), Infliximab (Remicade®) as well as Adalimumab (Humira®) and, since 2010, Golimumab (Simponi®) and Certolizumab (Cimzia®) are available. They differ on the one hand in the duration of action, and on the other hand in the mode of application (weekly s.c., 2-weekly s.c., 4-weekly s.c., and 2- to 3-monthly i.v. as infusion).

TNF-α inhibitors decrease both joint swelling and pain by up to >50% and reduce inflammatory parameters. These agents are also thought to inhibit, but not completely prevent, progression of radiographic changes. TNF-α inhibitors work particularly well in combination with methotrexate. They are used after insufficient response (3-6 months) or side effects of DMARD therapy. The prescription must be approved by the medical officer of the health insurer.

Contraindications include florid or latent infections (HIV, hepatitis, tuberculosis) and malignancies or recent malignancy therapy. Therefore, before starting a therapy, the search, resp. the exclusion of latent infections is required. The new TNF-α inhibitor certolizumab (Cimzia®) can even be used during pregnancy.

Fig. 2: Unhindered binding of TNF-α to the target cell.

Fig. 3: TNF blockade by monoclonal antibodies (infliximab and adalimumab).

B-cell depletion therapy: The introduction of the highly specific, anti-B-cell monoclonal antibody rituximab (MabThera®) in rheumatoid therapy in 2006 brought a new perspective to the Biological portfolio. Rituximab is a chimeric mouse/human monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to the transmembrane antigen CD20, which is present in large numbers on the surface of B cells. Rituximab has been used to treat non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma since 1997. The advantage of rituximab over TNF-α therapy is that there is not an increase in opportunistic or other infections. Rituximab is administered as an infusion (2 infusions 14 days apart), and treatment may be repeated at six- to 12-month intervals. However, the maximum effect occurs only after a few weeks to months.

Cell modulation therapy: Another biological therapy is available in the form of the T-cell modulator Abatacept (Orencia®). Abatacept is a fully human fusion protein that binds the co-modulatory molecules CD-80 and CD-86 to T cells, preventing their activation. It is therefore referred to as a T-cell co-stimulation blocker. Abatacept has been approved in Switzerland as a monthly infusion treatment since August 2007, and newly since April 2012 also as a subcutaneous form of administration (pre-filled syringe weekly). A slowing of disease activity as well as radiographic progression is suspected. In general, abatacept seems to have a favorable side effect profile, infusion reactions as well as opportunistic infections occur rarely, regarding malignancy risk no clear statement can be made based on the data so far. A small disadvantage is perhaps that the effect occurs only with a certain latency (3-6 months), but then lasts a very long time and in the further course hardly or not decreases.

Interleukin-6 blockers: interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a key cytokine in the inflammatory process and is specifically present in the tissues of rheumatoid synovitis in parallel with inflammatory activity. The monoclonal antibody tocilizumab (Actemra®) binds to soluble and membrane-expressed IL-6 receptors and inactivates IL-6 so that it can no longer exert a pro-inflammatory effect on the cell. Tocilizumab has been approved in Switzerland since 2009. Tocilizumab is administered in monthly infusions. A great advantage is the very rapid and convincing onset of action.

The experience with biologicals to date

Since 1998, more and more arthritis patients in Europe and also in Switzerland have been treated with the new biologicals, especially with TNF-α inhibitors, which are being used earlier and earlier in the treatment of RA. Supervision with these therapeutics by experienced specialists is necessary to detect and treat side effects in a timely manner. Unmanageable severe infections are still the most feared side effects of this group of drugs. Mild side effects include pain and burning at the injection site, increased sweating, blood pressure fluctuations.

In recent years, the formation of antibodies has been observed in individual cases of TNF-α inhibitor therapy , which lead to a decrease or loss of efficacy, so that it is necessary to switch to another biological. In infusion therapies, especially with monoclonal antibodies, very rarely more severe allergic reactions up to anaphylaxis may occur. Currently, these infusion therapies are performed under close supervision and by appropriately trained personnel. In our own patient population, none of these therapies had to be discontinued due to severe side effects.

Outlook

For all biologicals, further studies are needed regarding side effects, efficacy, and tolerability, especially for long-term administration. In view of the heterogeneous nature of inflammatory rheumatic diseases, it should be possible in the future to define even better which patients benefit most from which active agent; no actual guidelines exist on this yet. Existing preparations are continuously being supplemented or replaced by new generations of monoclonal antibodies, and work is also continuing on simplifying the method of application.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- The joint inflammation is reversible, but the secondary joint damage is not.

- The earlier RA is diagnosed and the more effectively the disease is treated, the better it is to avoid permanent joint damage and to slow and possibly prevent radiographic progression.

- In the current therapy of RA, the conventional treatment concept (treatment pyramid) is adapted to the respective activity of the disease.

- Biologicals have ushered in a new era in the treatment of rheumatic inflammatory diseases. Remission has become a realistic treatment goal.

Literature:

- Bartelds GM, et al: Dtsch Med Wochenschrift 2011; 136: 1410.

- Ernst J: Acta Rheumatol 2005; 30: 119-124.

- Forster A: Ars Medici 1/2009.

- Kyburz D: Rheuma Schweiz, issue 4, July 2011.

- Visser K, et al: Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69: 1333-1337.

- Grigor C, et al: Lancet 2004; 364: 263-269.

- Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, et al: Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 406-415.

- Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, et al: Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 6: 1227-1232.

- Quinn MA, et al: Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 27-35.

- Smolen JS, et al: Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 702-710.