Hypogonadism is a clinical syndrome in which dysfunction in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis results in decreased production of testosterone with clinical symptoms of testosterone deficiency. When should substitution take place?

Hypogonadism is a clinical syndrome in which dysfunction in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis results in decreased production of testosterone with clinical symptoms of testosterone deficiency. Pathologies at the level of the testis cause primary hypogonadism, while defects of the pituitary gland are called secondary and disorders at the level of the hypothalamus are called tertiary hypogonadism.

Symptoms of testosterone deficiency

The symptoms and signs of testosterone deficiency are basically divided into two groups. The first group, which includes the more specific symptoms, includes incomplete or delayed sexual development; reduced sexual -desire (libido); erectile dysfunction; gynecomastia; decreased axillary, facial, and pubic hair; reduced testicular volume (<5 mL); infertility; fracture tendency with minor trauma; low bone mineral density; and hot flashes. The second “non-specific” symptom group includes signs such as decreased energy and motivation, depressed mood, poor concentration and memory, sleep disturbances, mild anemia, decreased muscle mass and strength, increased body fat percentage, and decreased physical performance.

In young men, hypogonadism is more often characterized by symptoms of the first group, such as decreased libido and erectile dysfunction. This condition is most commonly caused by testicular or pituitary pathology, including hyperprolactinemia, pituitary adenomas, testicular disease, radiation exposure, or genetic conditions such as Klinefelter syndrome. In these cases of “classic hypogonadism,” testosterone replacement is indicated and has been shown to improve clinical symptoms.

Although these disease entities also exist in older men, they tend to be less common causes of testosterone deficiency compared to age-related (so-called functional) changes. Longitudinal studies showed that free testosterone levels decrease with age at an estimated rate of 1% per year in all men regardless of symptoms [1].

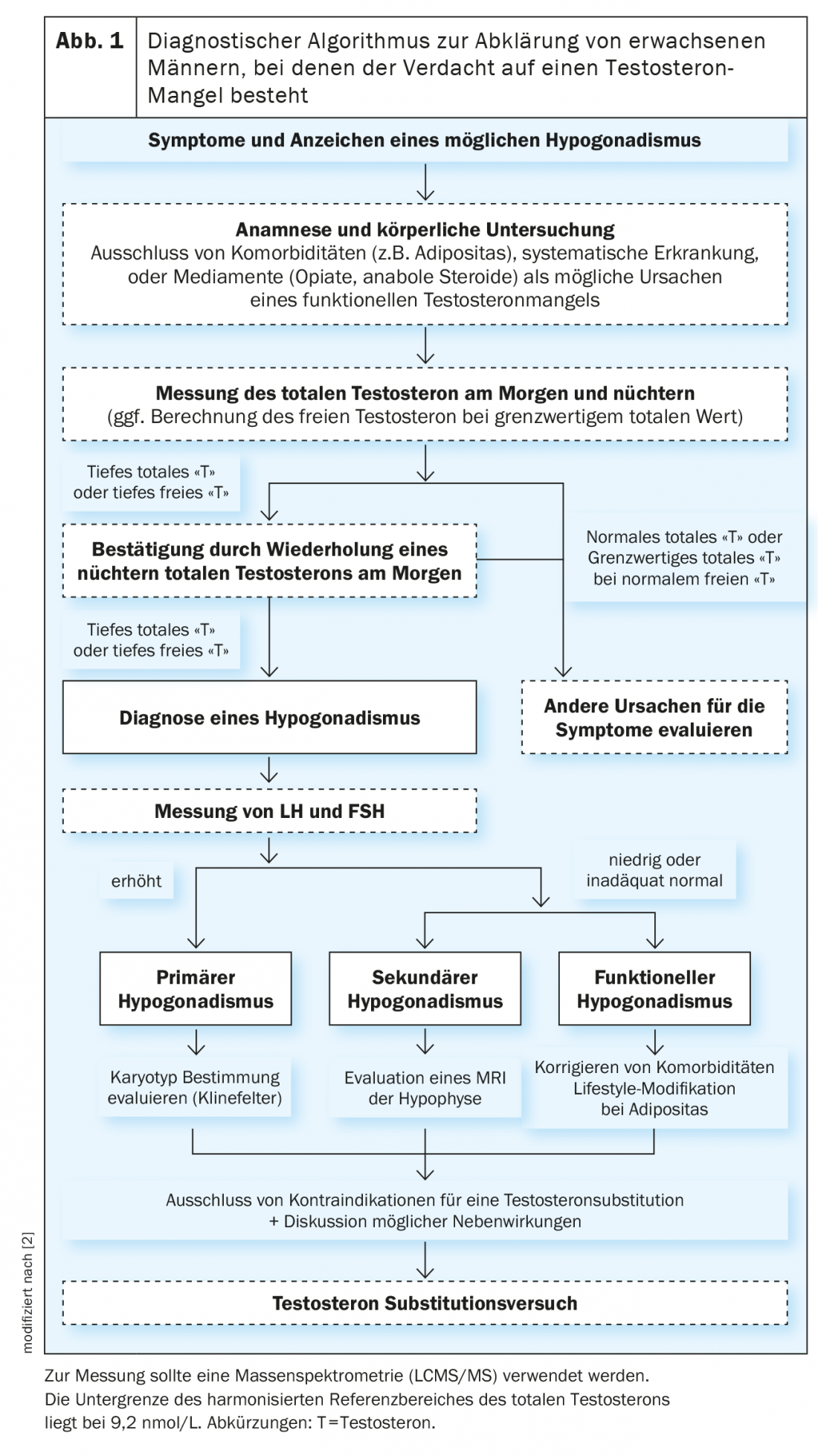

Diagnosis of testosterone deficiency

As part of the normal physiological aging process, there is a slow and steady decline in free testosterone, while total testosterone (BMI-adjusted) declines only slightly.

Testosterone concentrations show very pronounced circadian fluctuations with the highest values in the morning and a decrease throughout the day. Furthermore, it was shown that testosterone levels could be suppressed by food intake. Therefore, total testosterone should be measured in the morning between 7 am and 11 am in the fasting state [2]. It is important to confirm a low testosterone concentration in a second measurement, as 30% of men with an initial testosterone level in the hypogonadal range will have a normal serum testosterone concentration on repeated measurement. As a result, testosterone deficiency can never be diagnosed with just a single measurement.

Ideally, mass spectrometry (LCMS/MS) should be used for measurement, although immunoassays should be avoided as they are very inaccurate, especially at low levels. In men with conditions that alter sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) (for example, liver cirrhosis) or in whom total testosterone is near the lower limit of the reference range (8 -12 nmol/L), free testosterone should be calculated from total testosterone, SHBG, and albumin. A particular difficulty in the diagnosis of hypogonadism has been the high variability and lack of comparability of reference values between different laboratories. With this in mind, testosterone levels from four large cohort studies from Europe and the United States were measured using the same LCMS/MS method to establish a harmonized, uniform reference range. Here, a harmonized normal range was established, which is between 9.2 -33 nmol/L (264 – 916 ng/dL) in healthy non-obese men [3]. Overall, it can be concluded that the lower the testosterone level, the more likely the patient’s symptoms can be explained by actual hypogonadism.

Because the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis is suppressed during systemic inflammation, one should not test for testosterone deficiency when a patient is suffering from or recovering from an acute illness or is taking short-term medications (e.g., opioids) that similarly suppress testosterone concentrations.

Effects of testosterone therapy

Nowadays, topical testosterone gels, which have to be applied daily and can thus be dosed more finely, are mainly used for substitution therapy. Furthermore, intramuscular administration is still very common. With long-acting testosterone undecanoate, it only needs to be applied every 12 weeks once it is in steady state.

A recent series of testosterone trials (T-trials) involving men older than 65 years with serum testosterone levels <9.5 nmol/L found that topical testosterone therapy for one year resulted in improved bone density compared with placebo [4] and may improve pre-existing mild anemia [5]. However, testosterone substitution had no effect on age-related decline in mental performance [6]. As expected, treated men on testosterone reported moderate improvement in libido and erectile function, but without visible effects on physical performance or vitality [7].

Under testosterone therapy, measurement of testosterone and hematocrit should be performed at 3 to 6 months (depending on formulation) and at 12 months and annually thereafter. The goal should be to keep the testosterone concentration in the mid-normal range during treatment.

In addition, in hypogonadal men aged 55 to 69 years who are being considered for testosterone therapy and have a life expectancy of more than 10 years, the benefits and risks of screening for prostate cancer (determination of prostate-specific antigen, PSA) should be evaluated despite the lack of clear data of a prostate cancer risk.

If the goal of treatment is to induce or restore fertility, men with prepubertal hypogonadism most often require FSH and LH replacement (human chorionic gonadotropin or recombinant LH), whereas men with postpubertal hypogonadism usually require LH substitution only.

Functional testosterone deficiency can often be seen in obesity and metabolic syndrome. In this case, lifestyle modification and weight reduction should always be the first approach, after which normalization of testosterone levels will usually be seen [8].

However, many non-specific symptoms that are often treated with testosterone are due to normal aging or pathologies for which there are more effective, as well as safer, therapies. For example, depression should be treated with antidepressants, not testosterone; erectile dysfunction should be treated accordingly with phosphodiesterase inhibitors first. A meta-analysis of 40 studies found only weak correlations between low testosterone and nonspecific symptoms. Symptoms associated with low testosterone are also associated with chronic diseases, psychogenic factors, and substance abuse [9]. Erectile dysfunction, for example, is associated with diabetes mellitus, vascular dysfunction, and neurological disorders – all conditions commonly found in older men.

Are there cardiovascular risks?

Previous studies on the cardiovascular effects of testosterone are mixed. While large epidemiologic studies have shown an increased thromboembolic risk in the first few months of therapy, there are also prospective cohort studies showing a decreased cardiovascular risk in men receiving testosterone therapy. However, these observational studies carry the risk of bias because there was no randomized administration. It could therefore be that physicians prescribed testosterone to just healthier men or avoided prescribing it in men with comorbidities. Given this background, ultimately only a large-scale randomized trial to test the cardiovascular safety of testosterone replacement therapy will be able to answer the question of cardiovascular effects with certainty. From the randomized T-trials, it appears that there is an increase in noncalcified plaques in the coronaries with testosterone therapy, but this does not equate with certainty to increased cardiovascular risk and is therefore only a surrogate marker. Fortunately, the long-awaited large-scale TRAVERSE study is finally underway (clinicaltrials.gov NCT03518034), which will enroll a total of approximately 6000 patients with testosterone deficiency who will subsequently be followed for approximately 5 years. Until hard endpoint data are available, critical and carefully considered use of testosterone should be practiced.

Summary

Testosterone substitution should be initiated only when a clear testosterone deficiency can be diagnosed and symptomatology of hypogonadism is present. Klinefelter’s syndrome, pituitary insufficiency, hyperprolactinemia, or radiation exposure can lead to “classic” testosterone deficiency with hot flashes, loss of libido, infertility, osteoporosis, and decreased performance. In older or obese men with so-called “functional” hypogonadism, the indication for testosterone therapy is more difficult. Many symptoms are nonspecific, and therapy should therefore be started only when testosterone levels are clearly too low and the benefits and risks have been weighed. When clarifying a testosterone deficiency, it is of clinical relevance to always consider the presence of other causes of the patient’s complaints. Previous uncertainties, particularly regarding the cardiovascular effects of testosterone, will hopefully be answered by the TRAVERSE study in the coming years.

Take-Home Messages

- In general, the symptoms of testosterone deficiency are relatively non-specific. The most specific symptoms of testosterone deficiency include decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, gynecomastia, decreased body hair, and fracture tendency.

- Laboratory diagnosis of testosterone deficiency requires at least two measurements of total testosterone in the morning in the fasting state.

- Functional testosterone deficiency is often found in the context of obesity or the metabolic syndrome.

- Once a diagnosis of testosterone deficiency is made, the cause should be evaluated (primary vs. secondary hypogonadism).

- So far, cardiovascular side effects of long-term therapy with testosterone cannot be excluded.

Literature:

- Camacho EM, et al: Age-associated changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular function in middle-aged and older men are modified by weight change and lifestyle factors: longitudinal results from the European Male Ageing Study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 168, 445-455 (2013).

- Bhasin S, et al: Testosterone Therapy in Men with Hypogonadism: An Endocrine Society. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 103, 1715-1744 (2018).

- Travison TG, et al: Harmonized reference ranges for circulating testosterone levels in men of four cohort studies in the United States and Europe J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 102, 1161-1173 (2017).

- Snyder PJ, et al: Effect of testosterone treatment on volumetric bone density and strength in older men with low testosterone a controlled clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 177, 471-479 (2017).

- Roy CN, et al. Association of testosterone levels with anemia in older men a controlled clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 177, 480-490 (2017).

- Resnick, S. M. et al. Testosterone treatment and cognitive function in older men with low testosterone and age-associated memory impairment. JAMA – J. Am. Med. Assoc. 317, 717-727 (2017).

- Snyder PJ, et al: Effects of testosterone treatment in older men.

- N Engl J Med 374, 611-624 (2016).

- Corona G, et al: European Academy of Andrology (EAA) guidelines on investigation, treatment and monitoring of functional hypogonadism in males: Endorsing organization: European Society of Endocrinology. Andrology 8, 970-987 (2020).

- Millar AC, et al: Predicting low testosterone in aging men: A systematic review. Cmaj 188, E321-E330 (2016).

CARDIOVASC 2020; 19(4): 11-13