The 1st Swiss Heart Day was held in Zurich-Oerlikon in November. As part of the scientific program, representatives of various disciplines discussed current topics in cardiology. Why is Western society getting fatter and which measures actually help people lose weight? How do gender differences show up in the management of patients with heart disease? What are the special considerations for elderly patients prior to surgery?

According to Prof. Dr. med. Paolo Suter, University Hospital Zurich, more and more people are overweight or obese. The prevention of excessive weight gain is therefore becoming a central task for medicine and society in general due to the known health risks. New strategies are needed for this: “The classic food pyramid, which recommends a moderate but sufficient daily intake of food, is of course sensible in principle. However, the word ‘sufficient’ can be interpreted in very different ways. Ultimately, it remains the case that weight problems can only be solved by eating less,” says the speaker. “And to do that, you should know what the causes of the phenomenon are.”

One possible explanation lies in evolutionary biology. Certain bodily functions already possessed by prehistoric man become dysfunctional due to the modern lifestyle. While brain and brain function remained the same over time, the way food was obtained changed fundamentally: from hours of searching and hunting to permanent abundance within reach. “Our food program was evolutionarily created in a different environment than we have today. Foraging originally required a lot of brain and a lot of muscle. That’s why neural pathways for foraging are coupled with pathways for physical activity. Today, this program has largely lost its function,” Prof. Suter explained.

Restore functionality

The only way to solve the weight problem is to restore functionality. On the one hand, this means: move, move, move. The principle of “distance before time” applies. 30 minutes per day can be completely insufficient, provided that you cover too small a distance. The more kilometers per week, the greater the reduction in mortality risk.

Second, it means conscious and active cognitive restraint (“cortical/restrained eating”). This is not exactly easy, as the brain is very sensitive to food stimuli. Combined with the omnipresence of food, this is leading to the obesity epidemic. Today, the principle of “mind over metabolism” applies when dealing with food. Food intake is regulated by homeostatic-metabolic and non-homeostatic signals, with non-homeostatic stimuli (cognitive and environmental factors) playing the main role in modern times. The classic example is the aperitif, where people eat for social reasons without actually being hungry. These omnipresent “temptations” must be resisted.

Another important factor for the functionality of the program is sleep resp. Darkness. The latter is a metabolic signal that lets humans know when it’s time to sleep (and thus when to stop eating). In today’s 24/7 society, it is never really dark, which is why the circadian rhythm (internal clock) and the activity-rest cycle of humans get mixed up. You sleep less, which leads to chronic fatigue. This, in turn, increases appetite or hunger, eating frequency, and makes physical inactivity more likely, which can result in metabolic syndrome and chronic disease. BMI is lowest in those who sleep between seven and eight hours per night. Longer or shorter sleep duration leads to an increase in BMI. “The (re)synchronization of the circadian rhythm through a regulation of the daily routine including physical activity and sufficient sleep, as well as through regular, not too frequent eating (max. three times per day) is the third tip I would give to a patient with weight problems, in addition to exercise and cognitive restraint,” the expert concludes.

Gender Differences

Prof. Dr. med. Christine Attenhofer Jost, HerzGefässZentrum Zürich Klinik im Park, spoke about special features of women with heart disease. “Problematically, women in particular often view medications as ‘poison’ and are firmly convinced that they can cure themselves through healthy living or homeopathy. Many assume that, unlike the male gender, they need fewer or different medications. Not infrequently, we also see that a medication is taken, but in insufficient doses, according to the motto: I take this medication once or twice a week, that should be enough.”

These observations are supported by research: In fact, more women than men use complementary medicine overall [1]. Women are also less likely to receive guideline-compliant treatment, and compliance rates are lower than in men – among others, the use of statins in coronary artery disease (CAD), beta-blockers after acute myocardial infarction, and ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or beta-blockers in heart failure has been studied [2]. This is despite the fact that statins are at least as effective in secondary prevention in women as in men and that similarly good effects can be assumed in primary prevention. In addition, statins appear to reduce the risk of breast cancer recurrence and may even exert beneficial effects on the incidence itself [3]. With regard to the effect of aspirin for secondary prevention of CHD and acute coronary syndrome, there are also no relevant gender-related differences. In contrast, diuretics lead to side effects (including increased electrolyte disturbances) more frequently in women overall.

A broken heart

Finally, Prof. Attenhofer Jost presented a typical heart disease in women: Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy (stress cardiomyopathy/”broken heart syndrome”). Stress causes an excessive release of certain hormones, e.g. catecholamines or endothelins. These can damage the heart muscle cells of susceptible individuals and cause disturbances in blood flow. The ECG shows changes suggestive of an infarction, and the symptoms also point in this direction. However, cardiac catheterization usually reveals normal coronaries. The top of the left ventricle is balloon-like dilated and upwardly narrowed, and the heart no longer pumps properly.

The stressor may be a death or serious illness in the family. Also quarrels (e.g. in the partnership), an accident/assault or other physical stress can cause the suffering. Approximately 90% of women affected are middle-aged between 60 and 70 years [4].

Tako-Tsubo syndrome is very dangerous in acute cases, but unlike myocardial infarction, the heart usually recovers completely after a few days to weeks.

“In summary, there are few clinically relevant differences between men and women in the treatment of CHD. A major problem is mainly the lack of drug adherence. Furthermore, one should be (aware of) heart diseases such as Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy, which are much more common in women than in men,” the speaker concluded.

Risk stratification of the elderly patient prior to surgery.

According to Prof. Dr. med. Andreas Schönenberger, Spital Tiefenau, the main reasons why it is worth talking separately about risk stratification in elderly patients are comorbidity on the one hand and biological diversification on the other – both factors that become increasingly important in old age, which also makes the benefit-risk assessment all the more difficult. Is the patient physically active and independent or already significantly limited, perhaps even immobile and dependent on external assistance?

While there are various scores available to determine comorbidities, functional status is currently underreported in risk assessment. It is shown that surgical risk scores sometimes have comparable prognostic significance to scores based on geriatric functional assessment. In predicting 1-year mortality after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVI), measures of cognitive status, nutrition, mobility, activities of daily living, and the Frailty Index performed equally well as the two classic scores (STS and EuroSCORE). In predicting 30-day mortality, the EuroSCORE was even significantly worse than the Frailty Index [5]. Furthermore, geriatric scores such as the Frailty Index can reliably predict the functional status of elderly patients six months after TAVI, in contrast to the STS and EuroSCORE, which are unsuitable for this purpose [6]. With geriatric measurement, gaps or specific demands in the follow-up of TAVI are thus identified at an early stage.

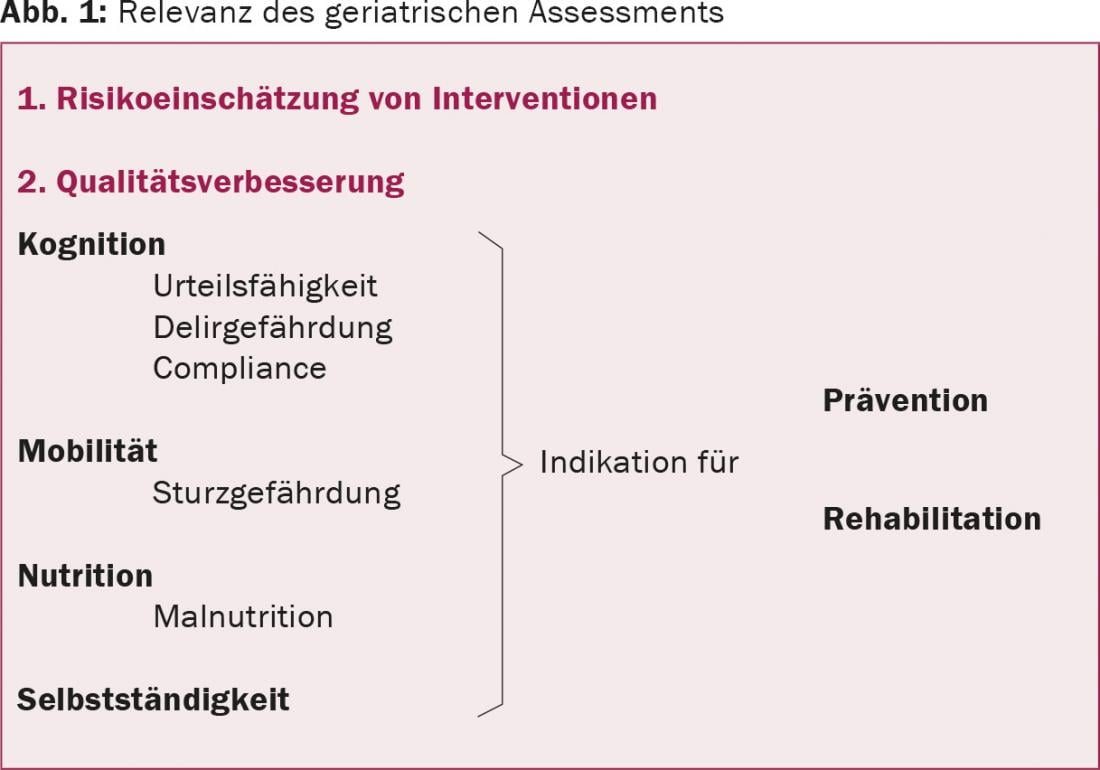

“In general, geriatric assessments imply measures for prevention and rehabilitation that reduce the risk of surgery and increase its benefit,” said the speaker (Fig. 1) . The risk of delirium should be urgently clarified preoperatively by means of a cognition test in order to reduce the frequency of delirium and thus mortality by means of preventive measures. Judgement is also key: “How do you know if your patient is capable of judgement and giving consent to intervention if you don’t know anything about their cognition?” asked Prof. Schönenberger.

In cases where the benefit of surgery is very great or the urgency is very high, a precise quantitative assessment of the surgical risk plays a secondary role anyway. “Here, the subjective impression and experience of the physician are already helpful,” noted Prof. Schönenberger. “In many cases, whether the patient arrives at the hospital with the suitcase packed by himself or has to be admitted already says a lot about the further course.” It is important to always consider the patient’s remaining life expectancy in the individual risk-benefit assessment of an intervention.

Source: 1st Swiss Heart Day, November 7, 2015, Zurich-Oerlikon

Literature:

- Klein SD, Frei-Erb M, Wolf U: Usage of complementary medicine across Switzerland: results of the Swiss Health Survey 2007. Swiss Med Wkly 2012; 142: w13666.

- Manteuffel M, et al: Influence of patient sex and gender on medication use, adherence, and prescribing alignment with guidelines. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014; 23(2): 112-119.

- Ahern TP, et al: Statins and breast cancer prognosis: evidence and opportunities. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15(10): e461-468.

- Templin C, et al: Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(10): 929-938.

- Stortecky S, et al: Evaluation of multidimensional geriatric assessment as a predictor of mortality and cardiovascular events after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2012; 5(5): 489-496.

- Schoenenberger AW, et al: Predictors of functional decline in elderly patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Eur Heart J 2013; 34(9): 684-692.

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(6): 32-35