At the fourth JHaS congress in Thun, Niklaus Labhardt, MD, Liestal, spoke about travel souvenirs in family practice. In particular, he addressed dengue fever, which is on the rise worldwide and, in combination with hemorrhagic complications, can have dangerous consequences if left untreated. Also, acute HIV infection and, of course, malaria should always be considered in travelers returning home.

Dr. med. Niklaus Labhardt, Liestal, introduced the problem with a case study: A 33-year-old woman returns to Switzerland after a two-week tour of Java followed by a six-day stay in Bali with severe back pain in the lumbar region and a slight macular rash over the dorsum of both feet. The day before the return trip, she feels a pronounced persistent cephalea, moving from frontal bilaterally to occipital. Hardly arrived at home, the fever rises rapidly (>39 degrees and shivering). With this, she now presents herself to the doctor. She feels that her elbow and knee joints are swollen, and she has severe pain in both hips. History reveals that she has suffered numerous mosquito bites and has not taken malaria prophylaxis. Status shows discrete conjunctivitis bilaterally. The so-called “thick drop” is negative three times.

“What are the most common diagnoses of fever after a stay in the tropics? In most cases, the diagnosis remains unclear (22%), followed by malaria (21%), diarrhea (15%), respiratory ailments (14%), and dengue (6%) [1]. Serology results for leptospires, chikungunya, and rickettsia were negative in this patient. For dengue, IgM and IgG levels were negative, but the antigen (“non-structural protein 1″, NS1) was positive. So the diagnosis was acute dengue infection,” Dr. Labhardt explained.

Dengue fever: A disease conquers the world

Dengue fever is transmitted by the Egyptian tiger mosquito (Stegomyia aegypti, formerly Aedes aegypti) primarily in the morning and late afternoon. This is an anthropophilic, i.e. preferring the cities “nervous flier”, which bites several times different people. There are four dengue virus types, and immunity is type-specific and long-lasting. In total, a full 2.5 billion people globally live in dengue risk areas (transmission Asia > Latin America > Africa), causing 50 – 100 million cases per year. 500,000 of them need to be hospitalized, mostly children.

“Dengue is expected to become more and more of a health concern for all of humanity in the 21st century, rather than previously thought to be a problem only for tropical countries. Autochthonous cases of dengue fever have already been documented in France and Croatia. The tiger mosquito is also making increasing inroads northwards across the Alps in Switzerland,” says Dr. Labhardt. There are three manifestations: the mild, atypical (undifferentiated fever, more common in children), the classical, and the hemorrhagic form (usually secondary to infection by another serotype). Symptoms of the classic form are:

- High fever

- Lymph node swelling

- Headache (retro-orbital, during eye movements)

- Myalgias and arthralgias

- Hyperesthesia (e.g. jet of the shower)

- Gastrointestinal Symptomatology

- Possibly respiratory symptoms

- Exanthema, often unspectacular (generalized redness in the first two days, measles-like rash on the third to fifth day).

The laboratory usually shows leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated transaminases.

If hemorrhagic complications occur, they usually occur when fever breaks, three to five days after symptom onset. The laboratory then shows severe thrombocytopenia and elevated transaminases. Clinically typical are petechiae, spontaneous bleeding, abdominal pain and deterioration of the general condition up to shock.

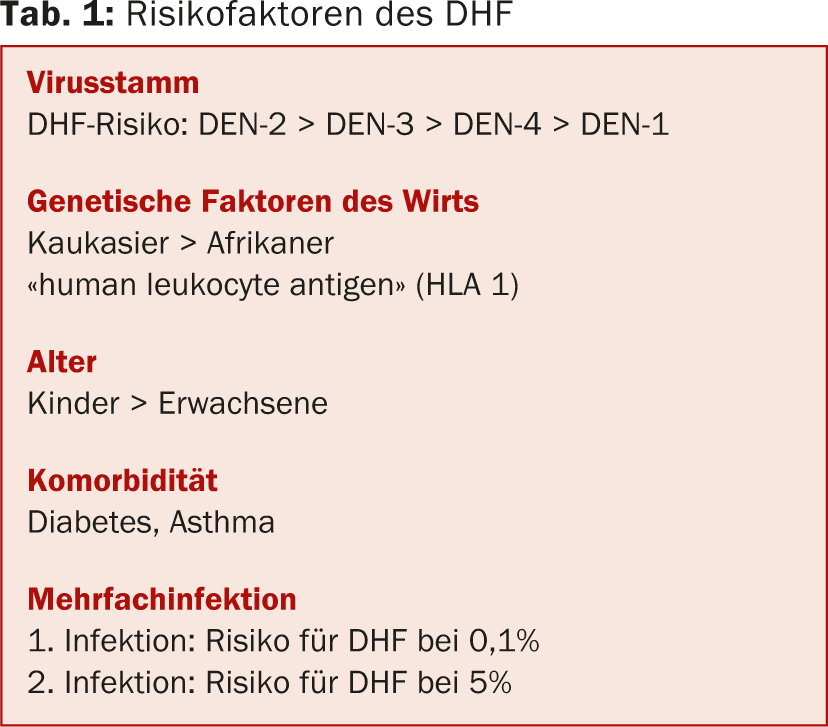

In addition, pleural effusions, ascites, and gallbladder edema occur. It is therefore important to follow up patients with acute dengue fever again clinically, even after fever has resolved. Risk factors for dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) are summarized in Table 1.

Therapeutic options and differential diagnoses

Treatment is symptomatic. NSAIDs should be avoided. Prognosis in the classical form is good (often protracted convalescence), in DHF less so (without therapy mortality up to 50%, with therapy in industrialized countries <1%).

A possible differential diagnosis to dengue is chickungunya (human-to-human transmission via Aedes mosquitoes). Clinically, the disease presents with high fever for two to five days, massive polyarthralgia (“breaking bone disease”), and exanthema approximately on the third day in over 50% of patients. Laboratory findings include lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia. Complications are very rare.

Acute HIV infection and malaria

“Let us now turn to acute HIV infection. Here it must be said in any case that an HIV test belongs to the assessment of every traveler with fever. In acute seroconversion syndrome, most experts today recommend an immediate start of treatment: early highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) rapidly lowers viral load and thus infectivity and probably improves long-term prognosis,” Dr. Labhardt summarized. For the primary care physician, this means that in the event of acute seroconversion syndrome, consultation with an HIV specialist should be immediate.

Approximately 216 million malaria episodes are reported annually worldwide, 81% of which occur in Africa. This is where most of the deaths occur. In Switzerland, the number of reported malaria cases is declining. Migrants living here and visiting their friends and relatives in Africa represent the largest risk group. They are less likely to consult a travel advisor and therefore less likely to take prophylaxis (e.g., Malarone®, Supracycline®, Mephaquin®) .

“Unfortunately, to date, there are no symptoms or clinical examination findings that allow us to diagnose or rule out malaria,” Dr. Labhardt said. The gold standard for malaria diagnosis remains the “thick drop”. In the absence of microscopy expertise, the malaria rapid test combined with blood smear can be used in an emergency to rule out severe malaria until the “thick drop” can be assessed by a person with expertise. Treatment of uncomplicated malaria is with Riamet® (4 tbl. 2× tgl. [D1] and 4 tbl. 1× tgl. [D2 und 3]) or Malarone® (4 tbl. 1× dgl. for three days).

Source: “Contagious or repulsive, in any case virulent: travel souvenirs in family practice”, seminar at the JHaS Congress, April 5, 2014, Thun.

Literature:

- Wilson ME, et al: Fever in returned travelers: results from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis 2007 Jun 15; 44(12): 1560-1568.

CONGRESS SPECIAL 2014; 5(2): 18-19