The workup of nontraumatic knee swelling is an exciting diagnostic challenge. The following article emphasizes the importance of careful history taking and goes into more detail about possible clinical findings and differential diagnoses. It also provides an overview of useful additional examinations that can be initiated on the basis of the previously established differential diagnoses.

An otherwise healthy 47-year-old patient presents to your office because of a mildly painful swelling of the right knee joint that has persisted without trauma for three weeks (Fig. 1).

How do you have to proceed in diagnostics? The first thing to determine is whether the cause is mechanical or inflammatory. Rather, a mechanical cause is indicated by e.g. trauma, age, pain in the foreground, pain especially with exertion, small effusion amount and no accompanying symptoms (Tab. 1).

If the history (and any additional symptoms already known) suggest an inflammatory cause, the next two important questions are whether other joints are affected (i.e., whether it is really only monarthritis or oligo- or even polyarthritis), and whether there are other concomitant (or previous) symptoms that allow a closer delimitation. Further additional clarifications are then based on the differential diagnostic considerations (Table 2).

The clinical examination of the knee joint can be groundbreaking, especially if there is a mechanical cause of knee joint swelling. Thus, contour coarsening, restricted motion, axis deviation, and crepitation should be looked for if osteoarthritis is suspected. Meniscal signs and signs of instability may be indicative of a lesion of the internal structures.

In contrast, in the presence of an inflammatory cause, the additional clinical local findings of hyperthermia or redness have only vague indicative significance. Even activated gonarthrosis may show hyperthermia.

Spondyloarthritis

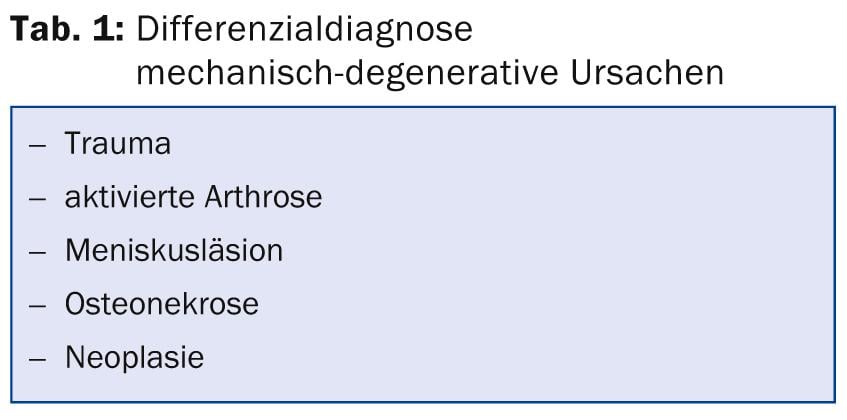

Whereas rheumatoid arthritis or the collagenoses (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus) are typically polyarticular (but may rarely have a monoarticular onset), monarthritis, particularly of the knee joint, is a more common manifestation of a disease from the spondyloarthritis group (formerly seronegative spondyloarthopathies) (Table 3, Fig. 2).

This group is known to include diseases characterized by the following common features: Inflammation of the spine and sacroiliac joints, inflammation of the peripheral joints (often oligoarticular and emphasizing the lower extremities), presence of enthesiopathies (tendon attachment inflammation), and association with HLA-B27 antigen. At most, there are simultaneous inflammations of the skin (typically psoriasis) or mucous membranes (reactive arthritis), the eyes or the intestines. Furthermore, there may be a causal relationship of the inflammation with certain pathogens (e.g. chlamydia, yersinia).

The most frequently monoarticularly inflamed joint here is the knee joint (incidentally occasionally also triggered by a minor trauma). With this suspected diagnosis, it is often possible to already anamnestic

other important clues are found.

Essential questions, then, are:

- Are other joints swollen?

- Is there inflammatory back pain (nighttime or early morning back pain, improvement on movement, morning stiffness)?

- Are there any enthesiopathies present (e.g., heel pain at the Achilles tendon insertion or plantar fascia)?

- Are there any skin/mucous membrane symptoms?

- Organ symptoms? (heart, lung, gastrointestinal, CNS)

- Previous or concomitant infectious symptoms (especially gastrointestinal or urogenital): Diarrhea, dysuria?

Reactive arthritis is usually acute and heals after a few weeks. Chronic courses are possible, however, so that reactive arthritis should also be considered in cases of prolonged joint swelling.

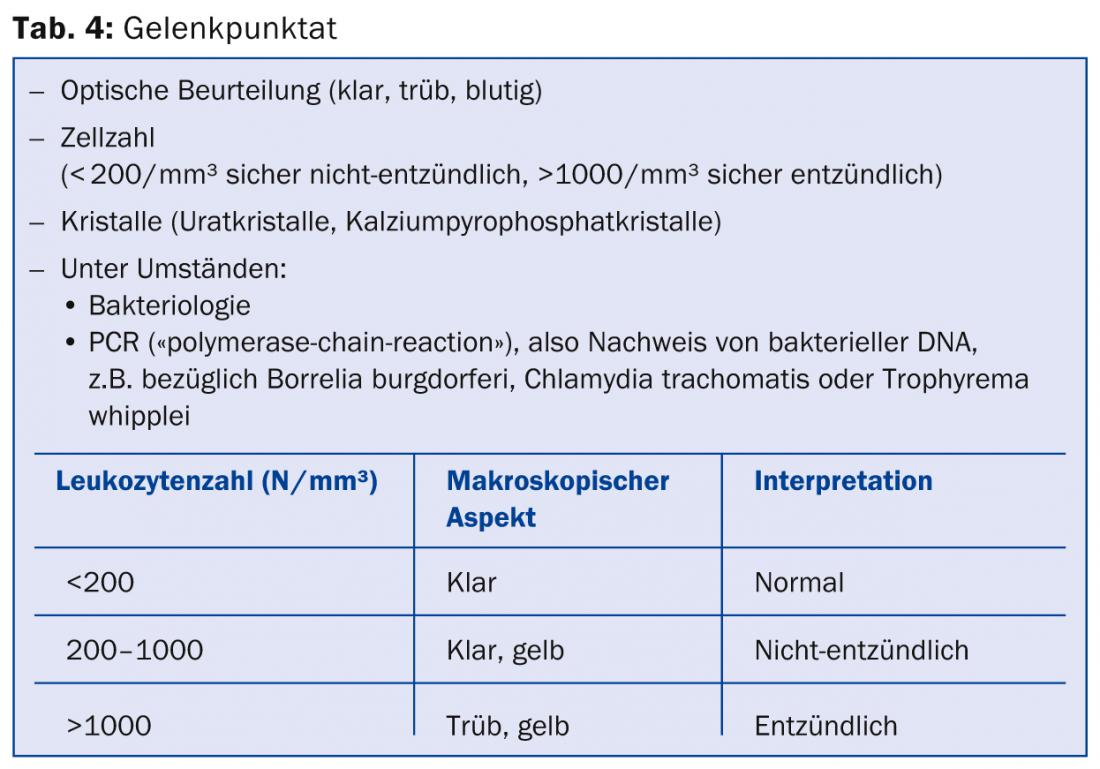

Crystal Arthritis

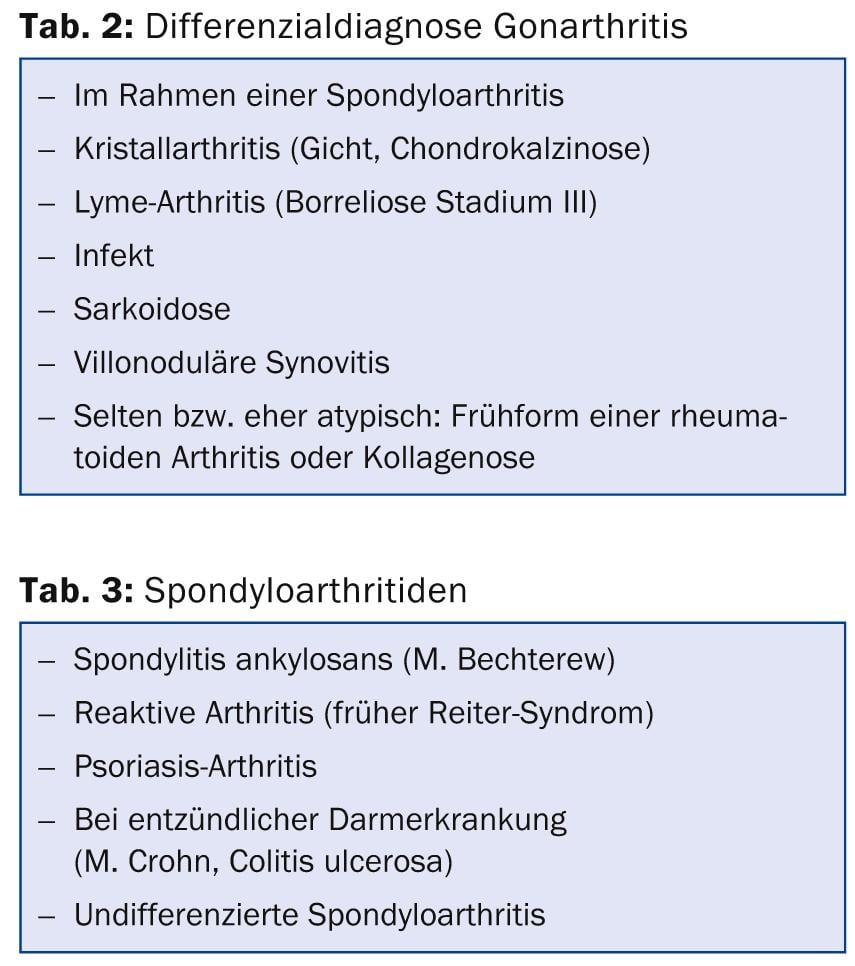

The knee joint is a predilection site for both gout and calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (chondrocalcinosis, pseudogout). Typical for such gonarthritis is the acute appearance of joint swelling and severe pain. Chondrocalcinosis is the most likely cause of acute gonarthritis in the elderly. Definitive diagnosis requires the detection of the corresponding crystals in the joint punctate. Evidence of chondrocalcinosis on radiograph or ultrasound makes this diagnosis likely but does not definitively prove it (Fig. 3).

Infection

A possible infection should always be included in the differential diagnosis of monarthritis. In particular, this must be considered in patients with impaired immunity (e.g., immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, drug abuse), after previous infiltration or surgery, and with typical accompanying infection symptoms such as chills or fever.

Lyme arthritis

Isolated gonarthritis (and not polyarthritis!) is the classic and by far the most common manifestation of stage III (late stage) Lyme disease. The infecting tick bite or any early manifestation (e.g., erythema chronicum migrans) occurred many months ago and are rarely ascertainable from anamnesis. A rather painless, usually large-volume effusion is typical. Serology from serum (at this point, usually only IgG antibodies are detectable) is of limited help for diagnosis. If positive, Lyme disease is possible but by no means proven. If serology is negative, this diagnosis can be excluded. For a reliable diagnosis, direct pathogen detection (PCR, “polymerase chain reaction”, i.e. molecular biological detection of pathogen DNA) in the joint puncture or, if necessary, in the synovial biopsy should be sought.

Joint puncture

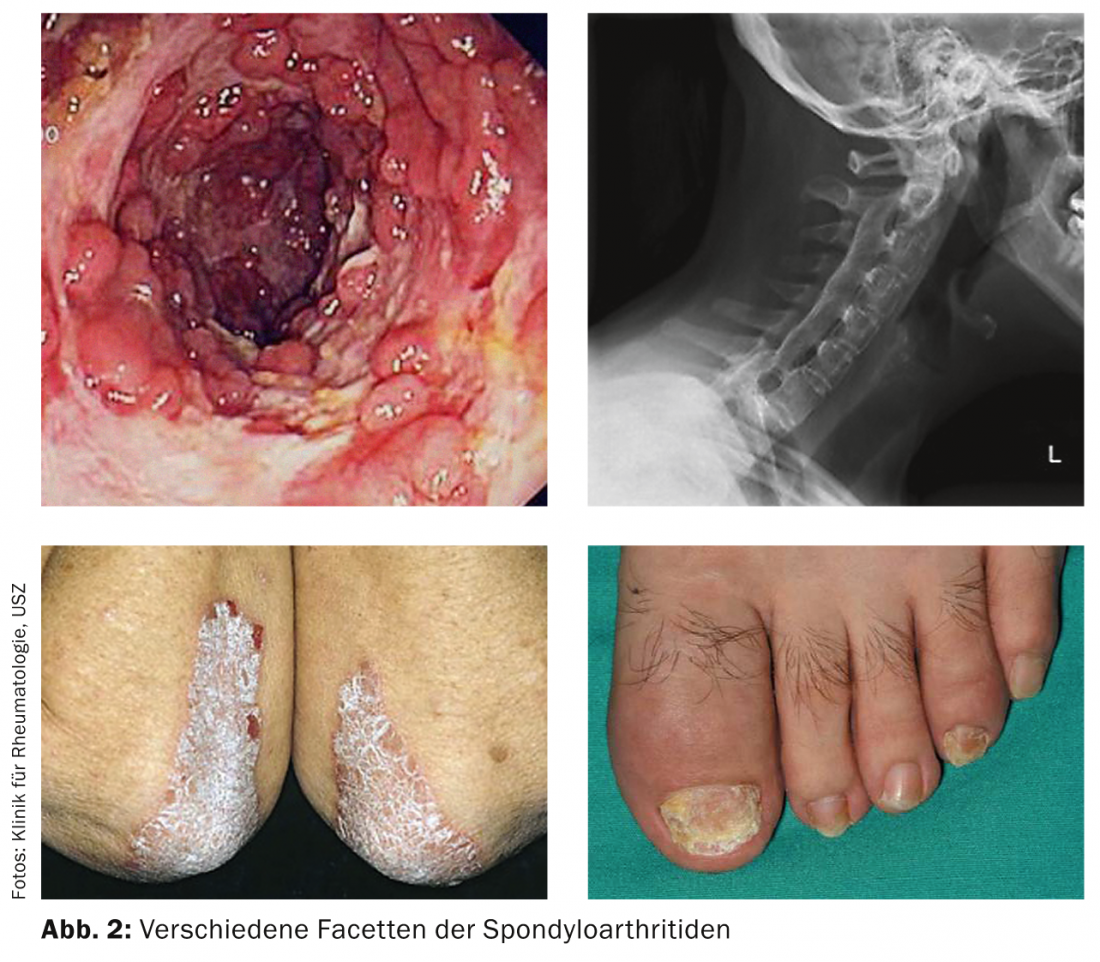

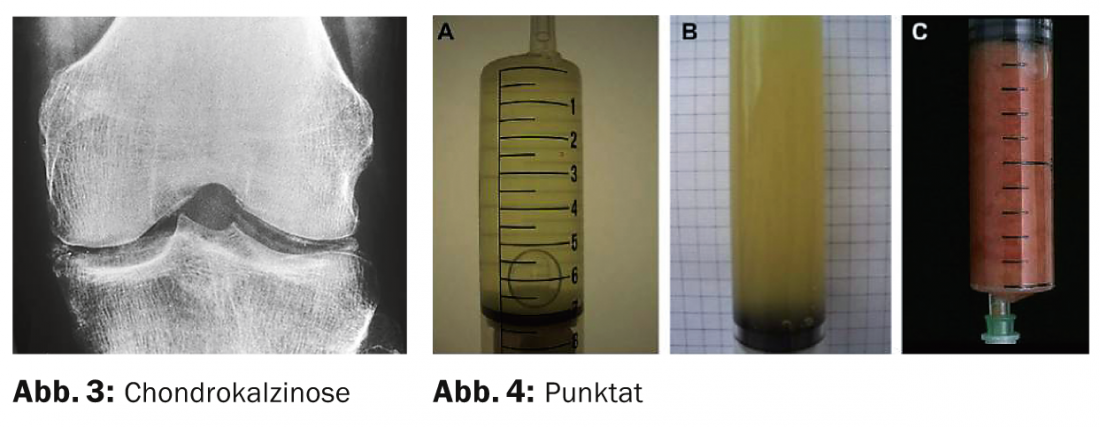

Both for definitive differentiation between a mechanical-degenerative and an inflammatory cause and for further diagnosis, examination of the joint effusion is indispensable. Thus, joint punctate analysis is crucial(Table 4, Figs. 4, 5, 6).

The higher the cell count, the more turbid the punctate. A very turbid punctate (purulent) primarily suggests an infection; however, very high cell counts may also occasionally be found in spondyloarthritides (e.g., psoriatic arthritis or reactive arthritis) or crystal arthritides. Even if crystals can be detected in a turbid, cell-rich joint puncture, a concurrent bacterial infection should be ruled out. A bloody punctate indicates a traumatic cause (hemarthrosis); however, bloody-tinged effusion may also be present in chondrocalcinosis or, rarely, severe osteoarthritis, or very rarely once caused by inadvertent injury to a synovial vessel by the puncture itself.

Knee joint puncture (Fig. 7) is performed with the patient lying down, most easily from the lateral side into the suprapatellar recess.

Mark the injection site about 1 cm below the upper pole of the patella, then correctly disinfect the puncture site according to the instructions of the product used (observe exposure time). Puncture is performed with strict adherence to the non-touch technique medial-cranial (e.g., with a 22G needle [schwarz]) into the suprapatellar recess. With the other hand, the recess can be compressed from the medial side. Wearing a mouthguard is recommended.

Meaningful laboratory

- A useful laboratory includes the following parameters:

- General: erythrocyte sedimentation reaction, CRP, blood count. Liver values and creatinine. Possibly TSH basal

- Rheumatoid factor, anti-CCP AK, ANA (antinuclear AK)

- Possibly Borrelia serology (excludes Lyme arthritis if IgM and IgG negative. If IgG positive, Lyme arthritis possible, but not proven. PCR in joint punctate whenever possible).

- Possibly LCR chlamydia or gonococcus in first morning urine (note: while chlamydia is reactive arthritis, gonococcus can be detected directly in joint punctate in terms of infectious arthritis).

Not very helpful and therefore meaningless: Uric acid in serum, other serologies in serum.

Meaningful imaging

A conventional x-ray is useful as a baseline. This can be used to look for osteoarthritis, traumatic changes, signs of chondrocalcinosis, or neoplasia.

If clinically uncertain, ultrasonography can be used to verify the presence of an effusion or synovitis. Ultrasound examination is also a good way of detecting calcifications of the cartilage or urate deposits (crystal arthropathy). Furthermore, if the cause of a joint effusion is inflammatory, there is often hyperperfusion of the synovium, which can be detected with power Doppler.

An MRI examination is useful if there is a clear mechanical cause (effusion in the non-inflammatory area) but this cannot be adequately explained by conventional imaging (e.g. damage to meniscus or ligaments, osteonecrosis).

A computer tomography is only useful for special questions (mainly concerning the bone). Scintigraphy is almost never indicated.

Andreas Krebs, MD

Andrea Stärkle-Bär, MD

Literature:

- Baker DG, Schumacher HR Jr: Acute monoarthritis. N Engl J Med 1993; 329(14): 1013.

- Sack K: Monarthritis: differential diagnosis. Am J Med 1997; 102(1A): 30S.

- Stanek G, et al: Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 2012; 379(9814): 461.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- First, the most likely differential diagnoses should be considered based on a careful history and significant clinical findings.

- Only then should specific additional examinations be initiated.

- The guiding factors are age, other complaints or findings both on the musculoskeletal system and extra-articularly as well as the analysis of the joint punctate.

A RETENIR

- Tout d’abord les diagnostics différentiels les plus vraisemblables doivent être considérés à la lumière d’une anamnèse minutieuse et des résultats cliniques importants.

- Il faut ensuite demander des exams complémentaires ciblés.

- L’âge, les autres affections ou résultats aussi bien de l’appareil locomoteur qu’extra-articulaires ainsi que l’analyse de la ponction articulaire fournissent des orientations.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(4): 17-20