Commensal microbes in the skin and mucosa play a key role in regulating the immune system and maintaining health. Influences that lead to a change in the composition of the microbiome and reduce its diversity can have pathogenic effects. This has been well studied for atopic dermatitis, but there are also recent findings on many other dermatological and other diseases.

The human microbiome describes the totality of all microorganisms that colonize a person’s body. The mucous membranes and the skin are colonized by commensal microbes in large numbers and diversity and form a symbiotic unit with them. It is becoming increasingly clear in what complex ways humans are influenced by microorganisms, that the immune system interacts with the microbiome, and that there are connections to various disease patterns. The fact that the composition of the microbiota varies greatly depending on the skin region partly explains predilection sites of certain dermatoses (e.g. acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis). Modern molecular genetic methods make it possible to analyze the DNA of commensal microbes quickly and efficiently. The PCR method (polymerase chain reaction) allows the detection of the DNA of all bacteria (microbiome) and fungi (mycobiome).

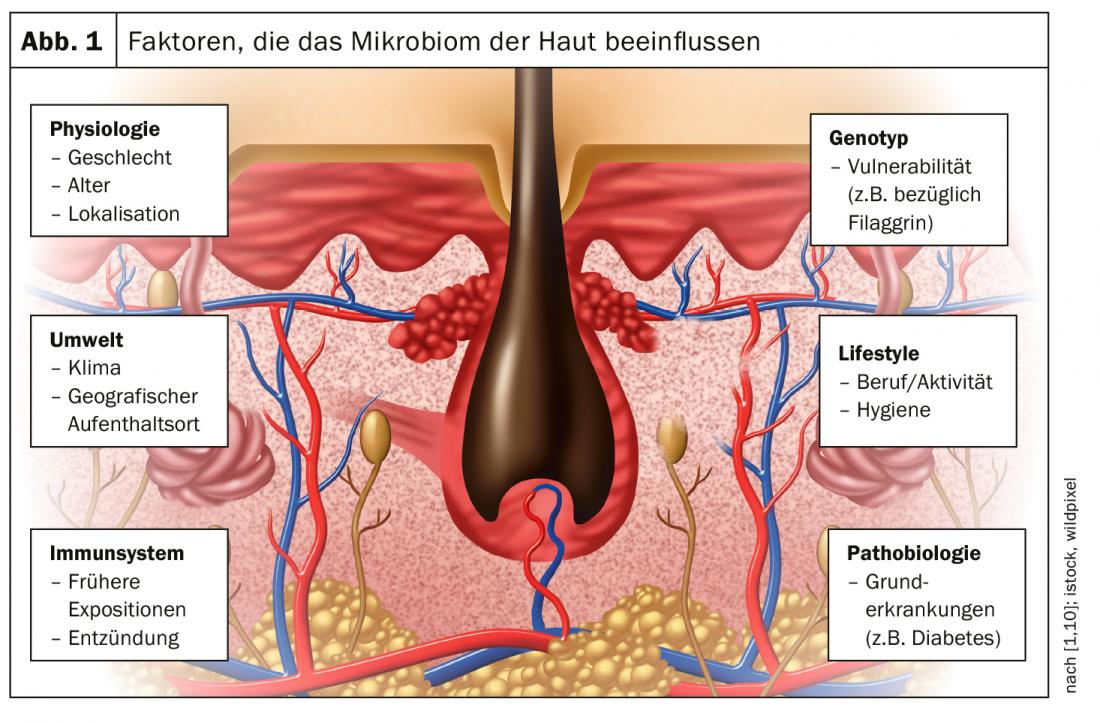

What influences the microbiome?

A variety of factors can affect microbial colonization (Fig. 1), including whether one is delivered as an infant by cesarean section or born naturally, type of diet, previous exposures, genotype, climatic conditions, lifestyle, and medications. The composition of the microbiome changes during development. This may also explain why the skin of an infant reacts differently in the first months of life than later [1]. There are also findings showing that children born by caesarean section have a higher tendency to obesity and atopy (asthma, atopic dermatitis). “Atopic diseases are strongly related to the colonization of the skin and gut microbiome,” explains Prof. Peter Schmid-Grendelmeier, MD, Head of the Allergy Ward at the University Hospital Zurich [1]. In one study, analysis of the fecal microbiota was used to infer whether someone suffered from obesity or asthma [2]. Antibiotic therapy can also alter the composition of the intestinal flora and contribute to an asthma tendency.

Atopic dermatitis: staphylococci reduce microbial diversity

“A broadly diversified microbiome in the gut and on the skin is associated with health,” the speaker explained [1]. Staphylococcal colonization typical of atopic dermatitis is associated with a reduction in microbial diversity, which correlates with exacerbations of atopic eczema [3]. At the cellular level, what happens is that staphylococci on the skin stimulate antigen-presenting T-cells and dendritic cells, which in turn leads to the formation of IgE and a weakening of the already degraded barrier function of the skin. The cytokine IL31, a major prurigogenic factor strongly implicated in the development of itch in atopic dermatitis, is upregulated. In addition, stimulation of antigen-presenting cutaneous lymphocytes takes place, resulting in T-cells being drawn into the skin and promoting maintenance of inflammation. The cause-effect relationship of the observed increase in the number of staphylococci at the expense of other microbiota in atopic skin has not yet been fully elucidated. It is not known exactly whether the disturbed microbial flora leads to increased growth of staphylococci or whether inflammatory skin changes occurring in the course of an incipient relapse cause particularly staphylococcus-friendly conditions. There are also many studies on this in children, as they are quite easy to perform, Prof. Schmid-Grendelmeier said. Analysis of the microbiome is possible using a non-invasive swab or stool sample. One of the studies demonstrated that the use of emollients positively influences the skin microbiome and skin barrier, which should be considered in a preventive treatment strategy regarding atopic dermatitis [4]. With regard to pet ownership, there are findings that show that children in whose environment dogs were kept in the first year of life are less at risk of developing atopic dermatitis – provided that the dogs can also go outside and thus introduce a certain microbial load into the living quarters [5,6]. This finding is not very old, ten to fifteen years ago the prevailing opinion was that pets should be strictly avoided in atopics [5].

Exploration of the microbiome in many other diseases.

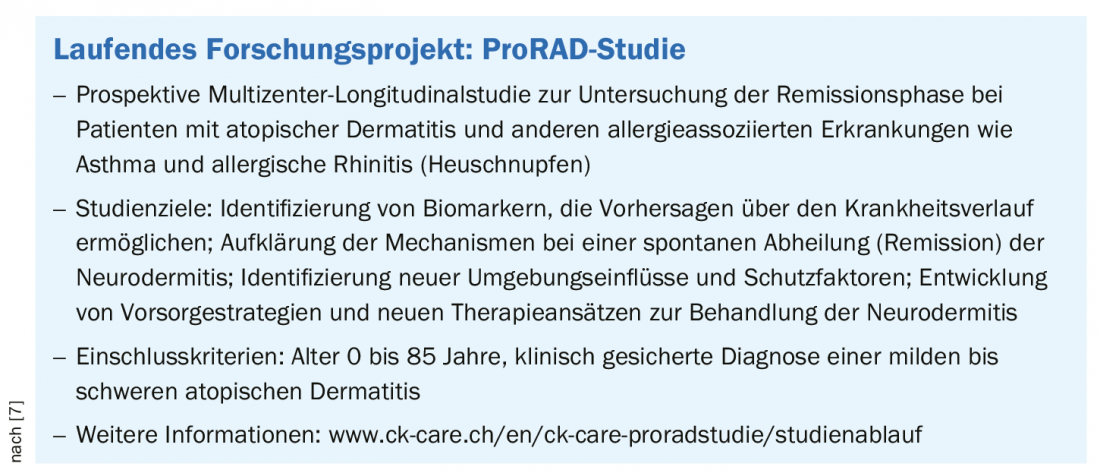

As mentioned at the outset, numerous projects are underway to study the microbiome. Among others, the University Hospital Zurich is also involved in the ProRAD study. One of the objectives is to study the remission phase in patients with atopic dermatitis and other allergy-associated diseases (Box) [7]. Recent publications also exist on the role of the microbiome in wound healing [8], melanocytic skin cancers [9], and psoriasis/PsoA [10]. In addition, the gut microbiome, as well as the much less studied mycobiome, is thought to have an impact in many other disease patterns [11]. According to current research, this applies, for example, to multiple sclerosis, arteriosclerosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, irritable bowel syndrome, obesity and liver disease, or even tumors. Even though microbiome research has provided some new insights in recent years, some questions are still unanswered.

Source: ZDFT 2020

Literature:

- Schmid-Grendelmeier P: Clinical cases from practice. The microbiome of the skin. Prof. Dr. med. Peter Schmid-Grendelmeier, Zürcher Dermatologische Fortbildungstage (ZDFT), 14./15.05.2020.

- Michalovich D, et al: Obesity and disease severity magnify disturbed microbiome-immune interactions in asthma patients. Nat Commun 2019; 10: 5711.

- Kong HH, et al: Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res 2012; 22(5): 850-859.

- Glatz M, et al: Emollient use alters skin barrier and microbes in infants at risk for developping dermatitis. PlosOne 2018; 13(2): e0192443.

- Bufford JD, et al: Effects of dog ownership in early childhood on immune development and atopic diseases. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2008; 38(10): 1635-1643.

- Roduit C et al. Prenatal animal contact and gene expression of innate immunity receptors at birth are associated with atopic dermatitis J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127(1):179-857.

- ProRAD Study, www.ck-care.ch/en/ck-care- proradstudy/study-procedure

- Verbanic S, et al: Microbial predictors of healing and short-term effect of debridement on the microbiome of chronic wounds. NPJ Biofilms Microbio 2020; 6 (1).

- Warner AB, McQuade JL: Modifiable Host Factors in Melanoma: Emerging Evidence for Obeisity, Diet, Exercise and the Microbiome. Curr Oncol Rep 2019; 21(8): 72.

- Myers B, et al: The gut microbiome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology 2019; 33(6): 101494.

- Aykut B, et al: The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL. Nature 2019; 574(7777): 264-267.

- Grice EA, Segre JA: The skin microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011; 9(4): 244-253.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2020; 30(4): 36-37 (published 8/24/20, ahead of print).