Differentiating between primary and secondary headaches requires a good medical history.

Around 90 percent of headaches are primary, i.e. benign headaches such as tension headaches or migraines. In the case of secondary headaches, further examinations such as laboratory tests, imaging and possibly a cerebrospinal fluid examination are often necessary.

Headaches are the most common neurological symptom in primary care [1,2]. The distinction between primary and secondary headaches is crucial for prognosis and treatment options [3]. According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3), primary headaches are categorized as follows [4]:

- Migraine,

- Tension-type headache,

- Trigeminal autonomic headache disorders,

- Other primary headaches.

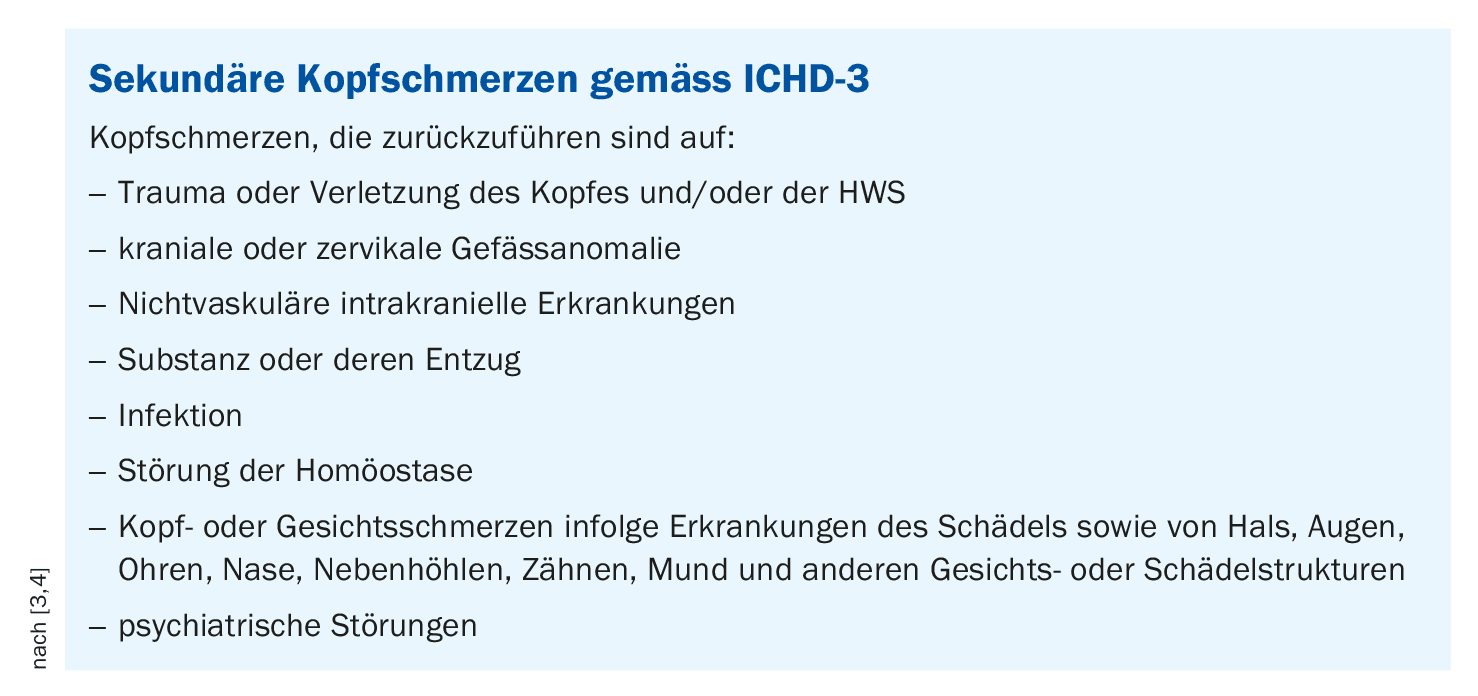

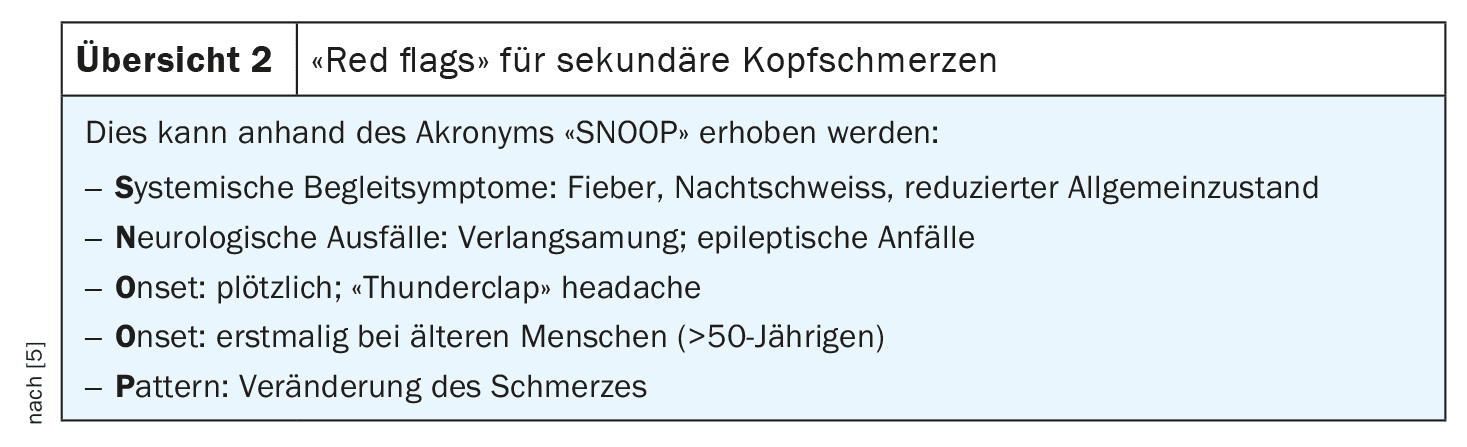

A relatively small percentage of patients suffer from secondary headache syndrome, which may require specialist care. A rough classification of secondary headaches according to ICHD-3 is shown in the box [3,4]. The most common secondary causes include meningitis, strokes, vasculitis or side effects of medication. The diagnostic classification of headache disorders is mainly based on the patient’s medical history. If there is a well-founded suspicion of secondary causes, imaging procedures (MRI, CT) may be used. PD Dr. Athina Papadopoulou, research group leader in the Department of Neurology at the University Hospital Basel, recommends taking a structured history and asking simple questions to find out more about the following aspects [5]:

- Time (duration, frequency, dynamics),

- Localization (unilateral, bilateral),

- Pain character (throbbing? stabbing?),

- Intensity (on a scale from 0 to 10),

- Accompanying symptoms (e.g. nausea, photophobia),

- Triggers (e.g. alcohol, physical activity).

Around 30% of cases are headaches that are localized bilaterally. However, the duration of the headache is a more important distinguishing feature than the localization, according to the speaker. According to an article published in the Lancet in 2021 by Ashina et al. only 1% of migraine cases require referral to specialists, the remaining cases can be managed in primary care [6].

Case example 1: classic migraine with visual aura

Dr. Papadopoulou reported a 28-year-old woman who complained of severe headaches, visual and sensory disturbances (tingling sensation in the left hand; face including tongue) [5]. Upon further inquiry, it turned out that the perceptual disturbances occurred prior to the seizure-like headache and that the visual disturbances were flickering, which began in the left field of vision and slowly increased binocularly. The visual and sensory disturbances lasted about 1 hour. The patient described the character of the pain as pressing/pounding and unilateral (right-sided). The pain intensity was severe (8 out of 10) and was accompanied by phonophobia and photophobia. The patient had already suffered such an episode two years ago. An MRI was performed at that time, which proved to be unremarkable. The medication history is also unremarkable, the patient only takes the pill. There is a family history of migraine on the mother’s side.

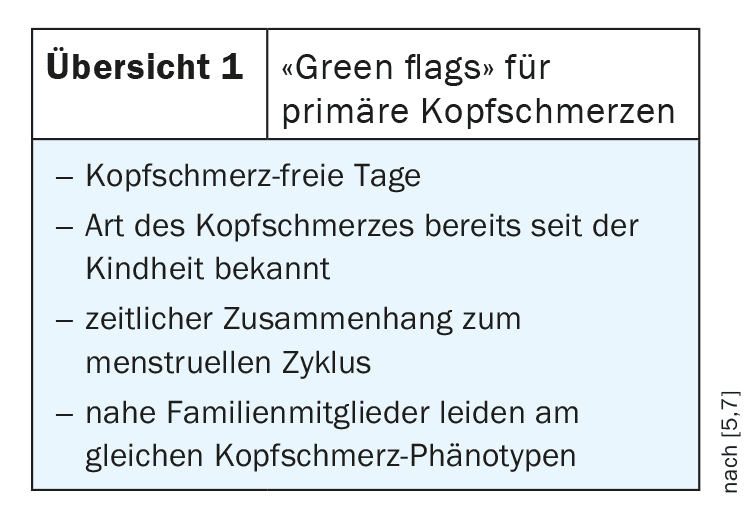

The speaker commented on this case example as follows: it was a typical case of migraine, which is why imaging is not necessary at the present time [5]. Pain occurring in attacks, accompanied by hypersensitivity to light and sound and possibly increased sensitivity to odors, are classic signs of migraine. Sometimes there is also nausea and vomiting. A migraine with aura, i.e. neurological irritation or loss of consciousness before the onset of the headache, is present in around a fifth of migraine patients. A visual aura – as in this patient – is the most common and is typically accompanied by visual disturbances, flickering and visual field defects. “An aura is an overexcitation in the brain, which usually begins in the visual cortex and spreads,” explained Dr. Papadopoulou [5]. A fibrillation that appears as a zigzag pattern is very typical for migraines. In terms of pain localization, the vast majority of migraine cases are unilateral headaches; bilateral headaches are much rarer. In summary, the present case was a typical history of primary headaches known from the past. There are patients who have suffered from migraine since childhood, which would be one of the “green flags” (Overview 1).

Case study 2: Polyneuritis cranialis

The medical history proved to be somewhat more complicated in the case of a 45-year-old patient with a new onset of headache, which had remained constant for 2 weeks with “peaks” of a few seconds/minutes [5]. The patient described the character of the pain as burning or electrifying during the peaks. The intensity was 8-10 out of 10 points. According to the patient’s description, the pain was localized on the left parieto-occipital side; the patient found touching the left-sided scalp unpleasant (allodynia). There are no rashes or blisters on the scalp, as might be the case with herpes zoster, for example. The patient denies accompanying symptoms such as nausea or photophobia. No previous illnesses are known. In this case, an MRI was ordered. According to Dr. Papadopoulou [5], this revealed a pathological accumulation of contrast medium in several nerves, indicating cranial polyneuritis. This was accompanied by progressive occipital neuralgia with facial nerve paresis and progressively worsening dysphagia. In addition, the left side of the face looked strangely altered. Further diagnostic clarification (e.g. liquid diagnostic evidence) revealed that neuroborreliosis was present due to a tick bite a few weeks previously.

This is a typical time course, as neurological manifestations of Lyme disease can occur weeks to months after a tick bite. In adults, meningoradiculoneuritis, a meningitis with simultaneous inflammation of the nerve roots in the spinal cord, is the most common. Around half of those affected suffer from cranial nerve damage, often resulting in unilateral or bilateral facial paralysis [8].

Congress: medArt Basel

Literature:

- Do TP, et al.: Barriers and gaps in headache education: a national cross-sectional survey of neurology residents in Denmark. BMC Med Educ. 2022 Apr 1; 22(1): 233

- Steiner TJ, et al.: Recommendations for headache service organisation and delivery in Europe. J Headache Pain 2011; 12: 419–426.

- Wijeratne T, et al.: Secondary headaches – red and green flags and their significance for diagnostics. eNeurologicalSci 2023 Jun 30; 32: 100473.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) 3rd edition. vol. 38(1) Cephalalgia; 2018. The International Classification of Headache Disorders; pp. 1–211.

- «Kopfschmerzen, wann muss ich ein Bild machen? Leitfaden für Internisten», Clinical Case Seminar, CCS 316, PD Dr. med. Athina Papadopoulou, medArt, Basel, 17.–21.06.24.

- Ashina M, et al.: Migraine: epidemiology and systems of care. Lancet. 2021.

doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32160-7. - Pohl H, et al.: Green Flags and headache: A concept study using the Delphi method. Headache 2021 Feb; 61(2): 300–309.

- «Zecken: So schützt man sich vor einer Neuroborreliose», https://hirnstiftung.org/2024/05/zecken-so-schuetzt-man-sich-vor-einer-neuroborreliose (last accessed 21.08.2024).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(9): 36–37 (published on 18.9.24, ahead of print)