The number of seniors in need of surgery is steadily increasing. At the same time, however, the perioperative risk also increases markedly with age. This makes the surgical decision and the accompanying measures much more complex.

“We are all aware of the development: The population, also in Switzerland, is increasingly ‘graying’,” says PD Dr. med. Patrick Y. Wüthrich, University Clinic for Anesthesiology and Pain Therapy, Inselspital Bern. “Estimates from the U.S. suggest that by 2030, more than two-thirds of all cancer cases will involve people over 65, further increasing the volume of surgery in this age group, which is already high at present.”

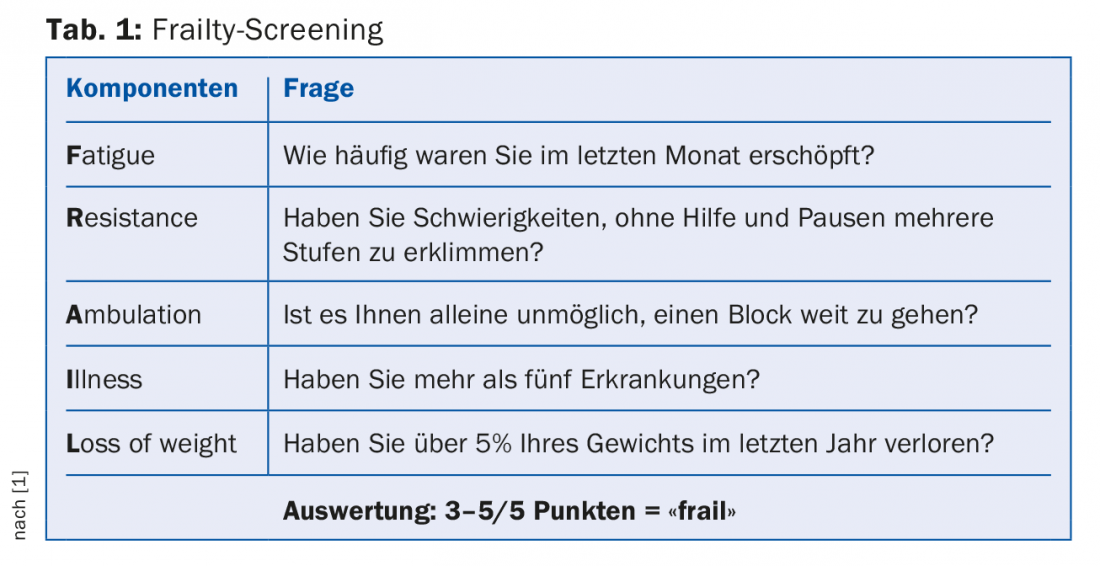

Now, the perioperative risk of older patients can be reduced, for example, by simply operating on them less frequently with curative intent. In fact, resection rates drop sharply after age 70 . Such an approach is not without scientific basis. As a consequence of the age-related decline in various physiological systems, so-called frailty develops (Tab. 1) [1] – a catch-all term that has also become increasingly accepted in the German language. Frailty leads to poorer tolerance or resistance to certain stressors, of which surgery is certainly one. Just over one-tenth of all people over 65 are “frail,” with women more affected.

“Frail” people (this is the makeshift German translation of the complex term), however, are by no means excluded from surgery from the outset. It is believed that with a considerable range of 25% to half of all frail patients are operated on anyway, although this significantly increases the risk of postoperative complications, length of hospital stay and institutionalization. Not only age (>70 years), but also the number of comorbidities (≥3) has a negative impact on outcome, e.g., in terms of mortality while still in hospital after radical cystectomy [2]. So, under what surgical conditions and with what pre/post care is surgery on elderly patients still possible?

Recognize patients at risk

Probably the most widely used score worldwide to predict mortality and morbidity or to estimate perioperative risk is the ASA risk classification. In fact, the ASA score is independently predictive of postoperative complications and mortality – this is of course also true for the specialty of urology [3]. Together with the concept of frailty, the predictive power can even be increased [4]. However, this is still not enough to ensure the smoothest possible operation. Integral to perioperative management of elderly patients are preparatory measures.

Preoperative situation

“One important issue why elderly patients suffer from postoperative complications is malnutrition. Such malnutrition is common, especially in comorbid individuals,” he said. Measurement of preoperative serum albumin (<3.5 g/dl) may play a significant role in the context – as studies again showed for radical cystectomy [5].

Nutrition should therefore be optimized in elderly patients as early as possible, but at the latest two to four weeks before surgery, e.g. with whey proteins (1.2 g/kg/d), carbohydrates (275 g/d), protein drinks (40 g/d) and of course – as is so often the case – vitamin D (1000 IU/d) and calcium (960 mg/d). This can alleviate sarcopenia and improve muscle strength. An anabolic “window” is created after physical activity, the consequence is a protein-saving effect postoperatively. Oral immune-boosting supplements can be started at least five days before surgery (e.g. Impact®). Preoperative carbohydrate “loading” should take place the evening before or the day of surgery (e.g. PreloadTM). In any case, the patient should enter the operating room hydrated [6]. Enteral bowel preparation should be avoided. To ensure that the fasting time is not too long, there is a six-hour preoperative grace period for solid foods and a two-hour preoperative grace period for liquids (including carbohydrate “loading”).

In addition, preoperative exercise programs to improve physical fitness should be sought. Cardiovascular function can be improved in the short term (three to four weeks) with repeated daily aerobic exercise longer than 10 minutes or a daily one-hour walk. Inspiratory muscle training, i.e. breathing against resistance, has been shown to be effective in reducing pulmonary complications.

The measures can be summarized as “prehabilitation”. “This phase starts as soon as the decision to operate is made,” the expert noted.

Intraoperative measures

“Frail patients are high-risk patients. They need to be off the operating table as quickly as possible. These cases are therefore not teaching cases; the best, most experienced surgeons (and anesthesiologists) should be used. In most cases, we cannot afford a re-operation, as mortality then increases by a factor of two to fourteen,” says Dr. Wüthrich. As the experience of the responsible person increases, the rate of readmission [7], but also mortality, decreases [8].

Regarding medication, short-acting anesthetics are preferable because they allow faster recovery with minimal side effects. The use of long-acting opioids should be kept to a minimum. Propofol and dexmedetomidine are among the drugs used. Overall, one should avoid too deep anesthesia, but also additional psychoactive substances (benzodiazepines), as the latter are more often associated with postoperative delirium and thus increased hospital mortality in “frail” patients. “Keep the patient warm, as hypothermia increases oxygen demand (leads to coagulopathy),” the speaker explained. Regional anesthesia is preferable (epidural).

Both fluid and salt overload should be avoided; this applies to the intraoperative as well as postoperative period.

Recreation

Recovery in terms of gastrointestinal function is one of the key postoperative components after radical cystectomy. Overload with salt and water impairs gastrointestinal function and is thus directly related to postoperative outcome [9]. Therefore, instead of NaCl 0.9%, a physiologically balanced solution such as Ringer ‘s lactate® or Plasmalyte® should be used and – as soon as the patient can drink freely – the postoperative i.v. maintenance (1 ml/kg/h) should be rapidly decreased. Routine use of nasogastric feeding tubes cannot be recommended. However, an early reintroduction of food makes sense. Clear drinks in the evening after surgery, additional energy drinks (e.g. Ensure®) twice daily on day 1 and slowly increasing soft food from day 2 onwards are recommended. If oral food is not tolerated, parenteral nutrition should be considered after approximately one week.

Although the approaches to (bowel) recovery after surgery are manifold, it seems that even simple measures can have an effect – e.g., chewing gum can stimulate the recovery of bowel function according to studies [10]. In addition, prokinetics also have their place here.

Source: 73rd Annual Meeting Swiss Society of Urology, September 6-8, 2017, Lugano.

Literature:

- Morley JE, et al: A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging 2012 Jul; 16(7): 601-608.

- Nayak JG, et al: Patient-centered risk stratification of disposition outcomes following radical cystectomy. Urol Oncol 2016 May; 34(5): 235.e17-23.

- Hackett NJ, et al: ASA class is a reliable independent predictor of medical complications and mortality following surgery. Int J Surg 2015 Jun; 18: 184-190.

- Lascano D, et al: Validation of a frailty index in patients undergoing curative surgery for urologic malignancy and comparison with other risk stratification tools. Urol Oncol 2015 Oct; 33(10): 426.e1-12.

- Johnson DC, et al: Nutritional predictors of complications following radical cystectomy. World J Urol 2015 Aug; 33(8): 1129-1137.

- Ylinenvaara SI, et al: Preoperative urine-specific gravity and the incidence of complications after hip fracture surgery: A prospective, observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2014 Feb; 31(2): 85-90.

- Jaeger MT, et al: Association Between Anesthesiology Volumes and Early and Late Outcomes After Cystectomy for Bladder Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Anesth Analg 2017 Jul; 125(1): 147-155.

- McCabe JE, et al: Radical cystectomy: defining the threshold for a surgeon to achieve optimal outcomes. Postgrad Med J 2007 Aug; 83(982): 556-560.

- Chowdhury AH, Lobo DN: Fluids and gastrointestinal function. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2011 Sep; 14(5): 469-476.

- Kouba EJ, Wallen EM, Pruthi RS: Gum chewing stimulates bowel motility in patients undergoing radical cystectomy with urinary diversion. Urology 2007 Dec; 70(6): 1053-1056.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(10): 33-35