Schizophrenia is one of the most severe mental illnesses and is also relatively common. The overall therapeutic goal in schizophrenia treatment should be to maintain or restore everyday functionality and quality of life. This requires adequate symptom control and good relapse prevention.

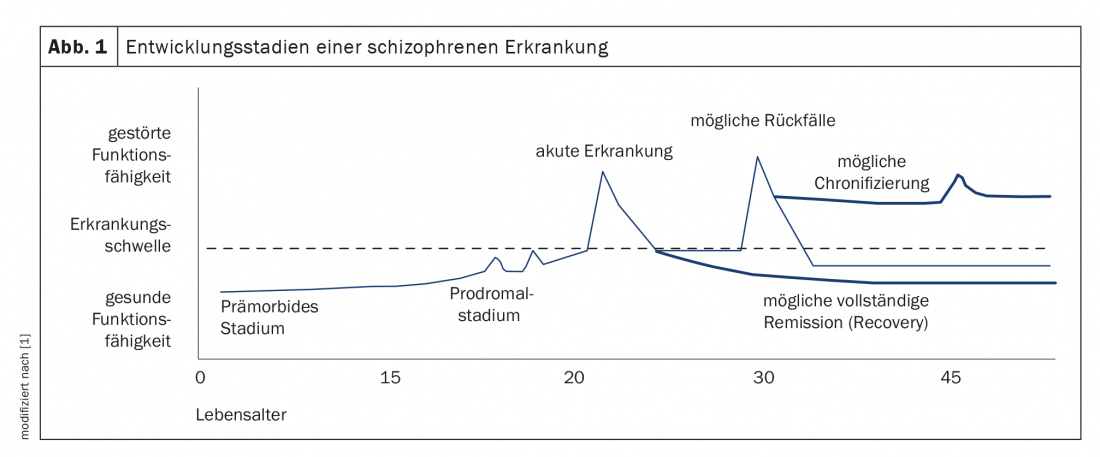

Schizophrenia is one of the most severe mental illnesses and is relatively common, with a prevalence of approximately 1% of the global population [1]. It is estimated that approximately 80,000 people in Switzerland suffer from schizophrenia [2]. In addition to symptom-related discomfort, it leads to significant impairment of occupational and psychosocial function and thus quality of life. According to WHO, it is among the top 10 reasons for “years of life affected by disability” [1]. In almost a quarter of patients, after successful treatment, there remains only one psychotic episode in a lifetime and mental health can be fully restored. Correspondingly, however, this is not the case in over 75% of those affected [1]. After phases of (almost) complete remission, you may experience repeated relapses – in some cases with considerable residual symptoms with cognitive and social impairments (Fig. 1). These make gainful employment only limited or completely impossible for about 70% of patients [1]. At the same time, schizophrenic psychoses cause considerable costs for the national economy. In Germany, it is estimated that approximately 2-4% of total health care costs are spent on schizophrenic patients. In Switzerland, the figures are likely to be similar.

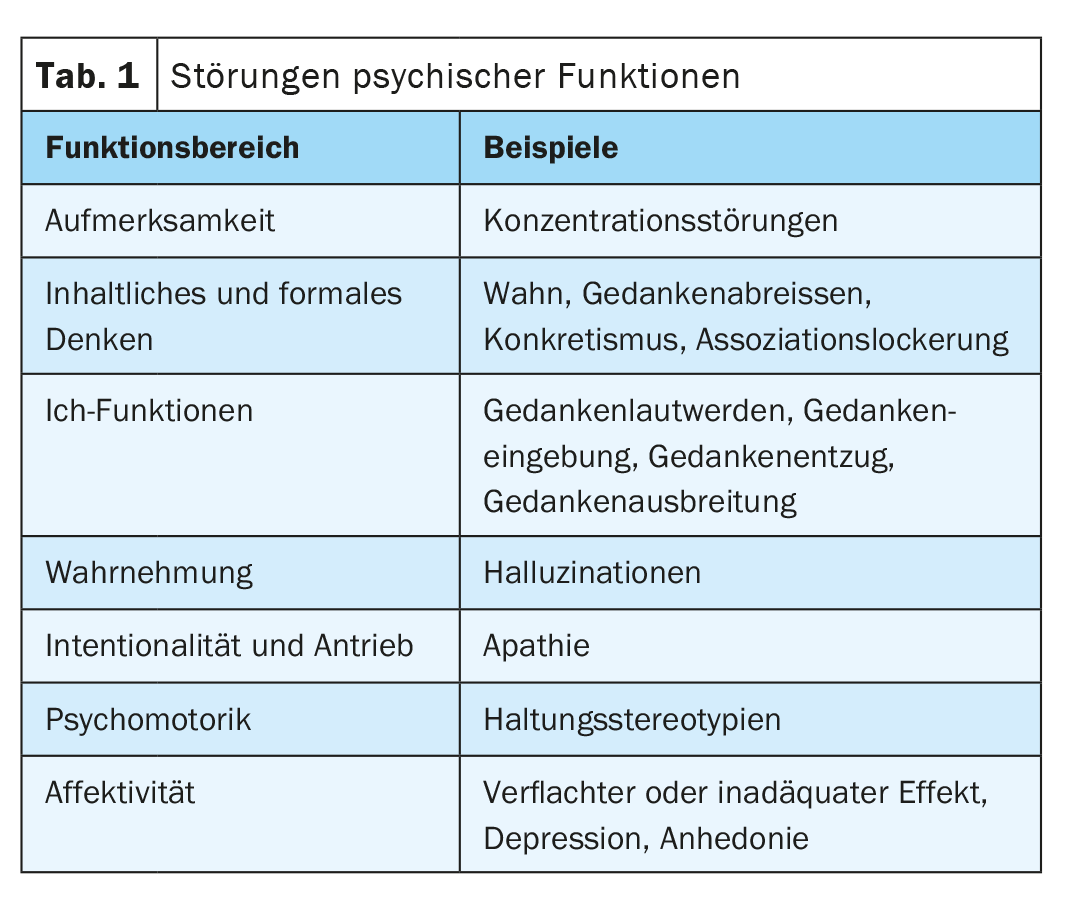

The development of antipsychotics with a favorable efficacy/side-effect profile was the first requirement for effective treatment management. This should be adapted to the respective phase of the disease as well as to the respective needs, requirements and wishes of the persons affected [3]. The overriding therapeutic goal is now the preservation of everyday functionality and quality of life. Back in 2011, a review summarized that new antipsychotics should preferably have a “balanced” pharmacodynamic profile that addresses the need for efficacy without compromising psychiatric or physical well-being. In addition, they should include a safe, rapid, and favorable pharmacokinetic profile, have a definable therapeutic window, and be available in different formulations [4]. Compared with previously available agents, they should ideally show at least similar efficacy for positive symptoms, agitation, and aggression, and better efficacy for negative symptoms or cognitive symptoms, relapse prevention, treatment-resistant illness, and related problems such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse (Table 1). Better tolerability and subjective acceptance by patients are also important to promote treatment adherence and continuation.

Patient-reported outcome parameters

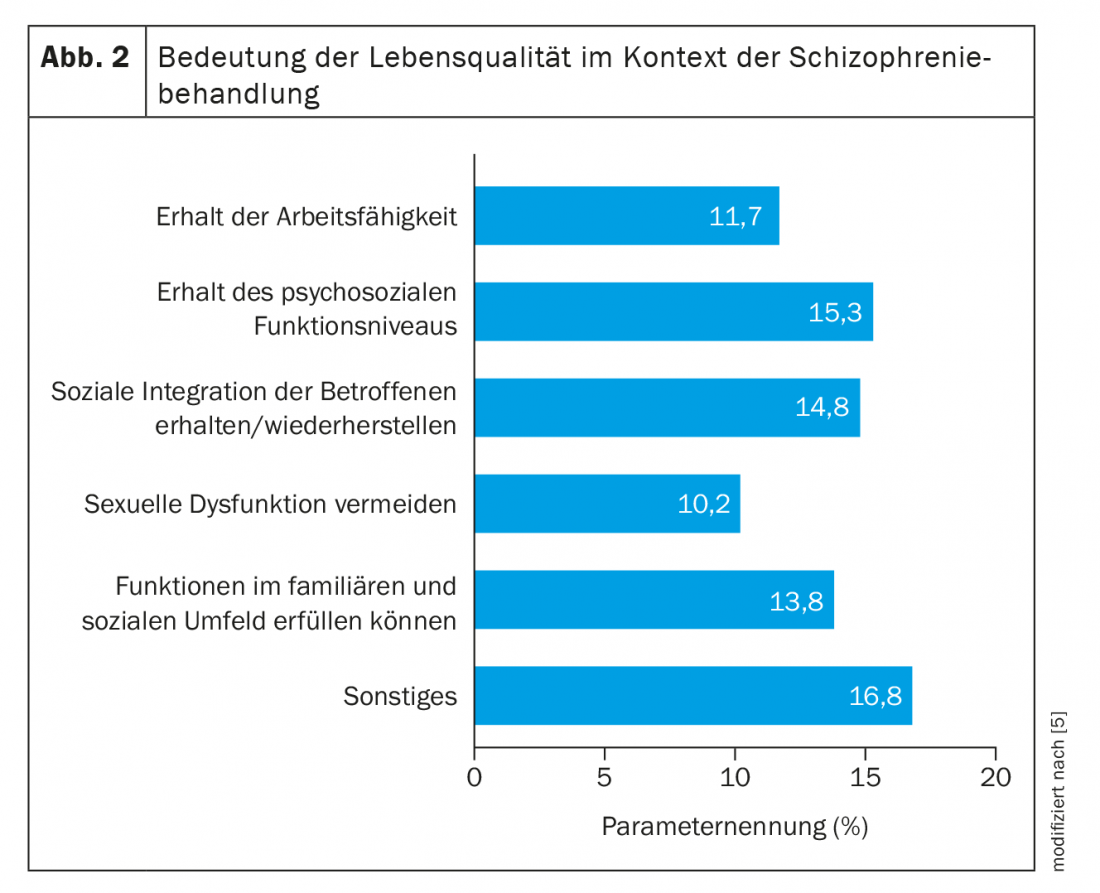

Since then, the aspect of patient-related outcomes (PROs) has moved more and more into the focus of considerations of patient-centered and optimized therapy planning. Mere symptom control is no longer sufficient today. Because this is not synonymous with health, well-being and quality of life. Rather, quality of life needs to be given greater consideration when assessing the success of therapy [5]. However, this fundamentally requires adequate adherence in order to achieve the corresponding effects. The doctor-patient relationship is important here, with good communication and shared decision-making. The patient-centered target criteria of a treatment include functional outcomes, functional recovery, subjective recovery and quality of life (Fig. 2) . Functional outcome is generally considered to be a level of (psycho-)social functioning. Deficits include, but are not limited to, problems with social role management, community participation, coping with daily life, occupation and household management, regular medication adherence, and basal self-care [6]. In the long-term course, neurocognitive impairments in particular are considered to be of great significance. Recovery, defined as symptomatic and functional remission and best possible quality of life, is nowadays the therapeutic goal of the guidelines. This requires multidimensional improvement and stabilization of the disease. To date, only one in seven patients achieves recovery over at least two years [7,8].

From symptom control to relapse prophylaxis

What does this mean for treatment management in practice? There is international consensus that the risk of recurrence can only be sustainably reduced by a combination of medicinal, psychotherapeutic and psychosocial measures [5]. In this regard, for effective relapse prevention, the ideal level of antipsychotic protection with the fewest adverse events must be found for each patient. But finding the appropriate pharmacologic intervention is not always straightforward. This is because there were hardly any differences between the individual antipsychotics in terms of their efficacy on positive and negative symptoms. Always provided they are taken regularly. A systematic review examined 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of schizophrenic adults [9]. A total of 54 417 studies were identified and ultimately 402 studies with data from 53 463 participants were included in the analysis. Individual effect size estimates were found to indicate that all antipsychotics reduced overall symptoms more than placebo (not significantly for six drugs), with mean effect sizes ranging from -0.89 to -0.03 (median -0.42). It could also be concluded that the differences between most of the drugs were not significant. In terms of efficacy and safety, many older antipsychotics, which allow few direct comparisons, also performed well compared with newer preparations. All in all, the researchers conclude that some differences in efficacy exist between antipsychotics, but they are more gradual in nature. The differences in side effects, on the other hand, are more apparent.

However, it does not hide the fact that older studies may have remained unpublished more often due to negative results. This makes an objective comparison much more difficult. Similar limitations are addressed by another meta-analysis with regard to placebo response [10]. This is because it proved to be the strongest single predictor of effect size in previous analyses. Now it was shown to be attenuated by a number of design and patient-related factors. In univariable analyses, more recent publication year, larger study size, more study sites, use of the PANSS scale rather than the BPRS scale to measure response, shorter washout periods, shorter study duration, lower mean age, and shorter disease duration were associated with greater placebo response. In a multivariable analysis, only the number of study participants and the mean age of the participants had an effect on the response to placebo. Ultimately, it appears that assessing differential efficacy of antipsychotics is very difficult in the absence of head-to-head studies.

Decision criterion side effects

However, the side effect spectrum is particularly relevant for good adherence. This is because in schizophrenia patients, adverse events are closely associated with medication non-adherence. Prevention, detection, and effective management of medication-related side effects are therefore important to maximize treatment adherence and reduce health resource utilization in schizophrenia. Sedative effects and weight gain have been found to be relevant for the patient and a frequent reason for discontinuation of therapy [11]. While some sedation in the acute setting may be considered beneficial by the treatment team. However, this should rather be achieved by a temporary addition of sedating substances such as benzodiazepines. In the long term, the use of antipsychotics with a sedating effect stands in the way of the overall therapeutic goals of functionality and quality of life.

In order to implement the optimal treatment management for the individual patient, it is therefore extremely relevant to know the characteristics and especially the side effect profile of the available pharmacological options [12–15]. These can then be adapted to the preferences of the person concerned and unwanted events can be avoided. In this way, not only adherence but also the therapeutic alliance is strengthened.

Since the discovery of chlorpromazine in 1952, first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) have revolutionized psychiatric care by facilitating hospital discharge and enabling large numbers of patients with severe mental illness to be treated in the community. Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) initiated a gradual shift away from paternalistic treatment of SMI symptoms toward a patient-centered approach that emphasized the goals important to patients-psychosocial functioning, quality of life, and recovery. There is evidence that SGAs have a better safety and tolerability profile compared to FGAs. The incidence of treatment-related extrapyramidal side effects is lower, and impairment of cognitive function and treatment-related negative symp-to-ms occur less frequently. However, treatment with SGAs is associated with a variety of adverse effects, of which treatment-related weight gain and metabolic abnormalities are of particular concern [12]. Here, switching to antipsychotics with a low risk of weight gain may be promising. Supplementation with weight loss medications, such as metformin or GLP1-RA may also prove to be an effective strategy [15]. In terms of metabolic side effects, there are also significant differences, with olanzapine and clozapine having the worst profiles and aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, lurasidone, and ziprasidone having the most favorable profiles. Increased baseline weight, male sex, and nonwhite ethnicity are predictors of susceptibility to antipsychotic-induced metabolic changes [14].

Conclusion

The chances of maintaining or restoring everyday functionality and quality of life in schizophrenic patients have increased significantly. Second-generation antipsychotics point the way and provide opportunities for patient-centered and optimized treatment planning.

Take-Home Messages

- The overall therapeutic goal in schizophrenia treatment should be to maintain or restore everyday functionality and quality of life.

- This requires adequate symptom control and good relapse prevention.

- Individual antipsychotics differ less in terms of their efficacy on positive and negative symptomatology, but do differ in their side effect profiles.

- Effective treatment management requires good adherence. This is based on shared decision making and the avoidance of patient-relevant adverse events.

- The main side effects for discontinuation of therapy are a sedating effect and weight gain.

- Knowledge of the respective characteristics of the available options helps to strengthen adherence and thus the therapeutic alliance.

Literature:

- www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Gesundheitsberichterstattung/GBEDownloadsT/Schizophrenie.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (last accessed 08.08.2021)

- www.gesundheit.bs.ch/gesundheitsfoerderung/psychische-gesundheit/krankheitsbilder/psychose/schizophrenie.html (last accessed 08.08.2021)

- S3 Guideline Schizophrenia; Available at: www.dgppn.de/_Resources/Persistent/88074695aeb16cfa00f4ac2d7174cd068d0658be/038-009l_S3_Schizophrenie_2019-03.pdf (last accessed 08.08.2021).

- Correll CU: What are we Looking for in New Antipsychotics? J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72: 9-13.

- Wietfeld R, Pechler S, Janetzky W, Leopold K: Therapeutic success in schizophrenia – is a change of perspective necessary? A discussion paper. Psychopharmacotherapy 2019; 26: 185-191.

- Harvey PD, Velligan DI, Bellack AS: Performance-based measures of functional skills: usefullness in clinical treatment studies. Schizophr Bull 2007; 33: 1138-1148.

- Jaaskelainen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, et al: A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2013; 39: 1296-1306.

- Kohl S, Kuhn J, Wiedemann K: Rationale and objectives of drug therapy for schizophrenia. Psychopharmacotherapy 2014; 21: 85-95.

- Huhn M, Nikolakopoulou A, Schneider-Thoma J, et al: Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2019; 394: 939-951.

- Leucht S, Chaimani A, Leucht C, et al: 60 years of placebo-controlled antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: meta-regression of predictors of placebo response. Schizophrenia Research 2018; 201: 315-323.

- DiBonaventura M, Gabriel S, Dupclay L, et al: A patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a crosssectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2012; 12: 20.

- Solmi M, Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, et al: Safety, tolerability, and risks associated with first- and second-generation antipsychotics: a state-of-the-art clinical review. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2017; 13: 757-777.

- Citrome L: Activating and Sedating Adverse Effects of Second-Generation Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Schizophrenia and Major Depressive Disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2017; 37: 138-147.

- Pillinger T, McCutcheon RA, Vano L, et al: Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7: 64-77.

- Marteene W, Winckel K, Hollingworth S, et al: Strategies to counter antipsychotic-associated weight gain in patients with schizophrenia. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 2019; 18: 1149-1160.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2021; 19(4): 6-9.