Dementias and depression are the most common neuropsychiatric disorders of aging. Due to a largely overlapping symptomatology, the exact diagnosis is difficult and often cannot be made in a single cross-sectional examination. Depressive syndromes in old age can develop on the basis of dementia and, conversely, a history of depression means an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease or even vascular dementia. In addition, depressive syndromes in old age can occur with cognitive impairment without dementia pathology. Anamnestic, somatic, neurological, neuropsychological, and psychopathological examinations, imaging, and CSF diagnostics can only provide clues. The further clinical course is decisive.

Dementia, along with depression, is the most common neuropsychiatric disorder of aging. Currently, the number of patients with dementia in Switzerland is about 110,000. The number of new cases is estimated to be up to 25 000 per year, with an increase to up to 220 000 persons in 2030 [1]. Prevalence rates for depression in people over 60 years of age vary from 7% to 25% [2–4], with prevalence rates for geriatric depression still much higher than in the overall population, especially in nursing homes and homes for the elderly [5].

Despite the high number of patients with geriatric depression, the condition is often undiagnosed [4] and not adequately treated [6]. Even in patients with dementia, only one-third of patients receive the exact diagnosis [7]. Only one in four patients receives antidementia pharmacotherapy and only one in five patients receives dementia-specific nonpharmacologic treatment [7].

In addition to the fact that dementia and depression are often not recognized, especially early enough, making the correct diagnosis for both conditions is a major challenge.

This is mainly due to the fact that depression without underlying dementia and dementia with depressive symptoms are almost identical on the phenomenological level.

Symptoms

Dementia is defined by the leading symptom of cognitive impairment, primarily memory impairment. In addition, in the context of secondary dementia symptoms, the so-called behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), various psychiatric disorders (aggression and agitation, psychoses, hallucinations, affective disorders). Depressive syndromes are very common in all stages of dementia, especially Alzheimer’s dementia [8]. Incidence rates of up to 40% of depressive disorders in AD have been reported [9]. Few studies are available in non-Alzheimer dementias. Here, however, it is shown that in vascular dementia the frequency for depression is even greater than in Alzheimer’s dementia, with a percentage of over 40% [10,11]. In this case, when depression occurs in the context of an already diagnosed (i.e., known) dementia, the depressive presentation, which may reach the criteria of major depression according to ICD-10, is to be classified as depression in the context of the underlying dementia. On the other hand, depression is characterized by the main symptoms of depressed mood, loss of interest and drive. Very often, other secondary symptoms such as sleep disturbances, loss of appetite and also cognitive disturbances occur, which can take on such a strong expression that they dominate the clinical picture.

In particular, old-age depression is characterized by the occurrence of pronounced cognitive disturbances [12], which are perceived by patients as being so severe that they believe they are suffering from Alzheimer’s disease.

For many years, the cognitive disorders associated with depression were referred to as “depressive pseudodementia.” This term assigns cognitive impairment in depression a secondary role within the affective disorder and implies reversibility of cognitive impairment upon improvement of depression. However, various studies show that in the majority of depressed patients, despite good remission of depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment persists or only partially remits under antidepressant treatment [13].

This and other findings (imaging) led to the conclusion that the group of old-age depression is a very heterogeneous group, determined to a different extent by functional disorders (more depression) and especially structural damage (more dementia). The transition between the two poles (purely functional vs. purely structural disorder) is fluid, i.e., disorders on both dimensions are present to varying degrees, so that it is not possible to say exactly whether the disorder is more likely to be classified as depression or dementia. This fits with findings showing hippocampal volume reduction in younger patients with depression as well, depending on the duration of untreated depression [14].

It is in this context that studies indicating a close link between depression and Alzheimer’s dementia, the most common neurodegenerative dementia, should be seen. Depression can be both a prodromal stage and a risk factor for the onset of AD [8]. Depression occurring earlier in adulthood is associated with a more than twofold increased risk of developing dementia later in life [15–17], with an increase in dementia risk also shown with each depressive episode [18].

Interim summary

Depressive syndromes in old age can arise – regardless of the provenance of cognitive disorders – on the basis of a dementia-related illness. With a corresponding depressive history, there is an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease or even vascular dementia.

However, depressive syndromes can also exist in old age as a purely depressive illness with the appearance of cognitive impairment without the presence of dementia pathology. The cognitive impairment may then be reversible with adequate treatment.

Procedure in diagnostics

Medical history and previous information: If a patient has been previously diagnosed with dementia and has also developed depression, the depression should be seen in the context of the dementia-related illness and treated according to the treatment recommendations (e.g., Swiss Treatment Recommendations for the Treatment of BPRS, [19]). There are different hypotheses about the etiology of depression in dementia. Depression may develop under the increasing impairment in daily life associated with the onset of dementia [20], but it may also be related to biochemical changes at the neurotransmitter level, especially monoaminergic.

Patients who present with a depressive state and pronounced cognitive disorders are particularly difficult to diagnose.

Since the probability of dementia increases at an age of 60 years and older and dementias as described above are often associated with depression, an underlying (possibly incipient) dementia, but also other somatic causes of depression (e.g., neuroendocrine, cardiovascular disorders) must always be considered in the presence of a depressive state in the elderly.

For this reason, in addition to psychiatric depression diagnostics, parallel examinations should be performed that are indicated in the context of dementia diagnostics.

Diagnosis of dementia with regard to the differential diagnosis of depression

Besides the detailed medical history, especially of a detailed External history about the development of the disease and the impairment in everyday life, can result from an exact somatic and neurological examination already reveal evidence of a dementia basis for the depression, such as Parkinson’s symptoms (Lewy body dementia), tendency to fall (progressive supranuclear gaze palsy), reflex disorders (frontotemporal dementias with neurological courses).

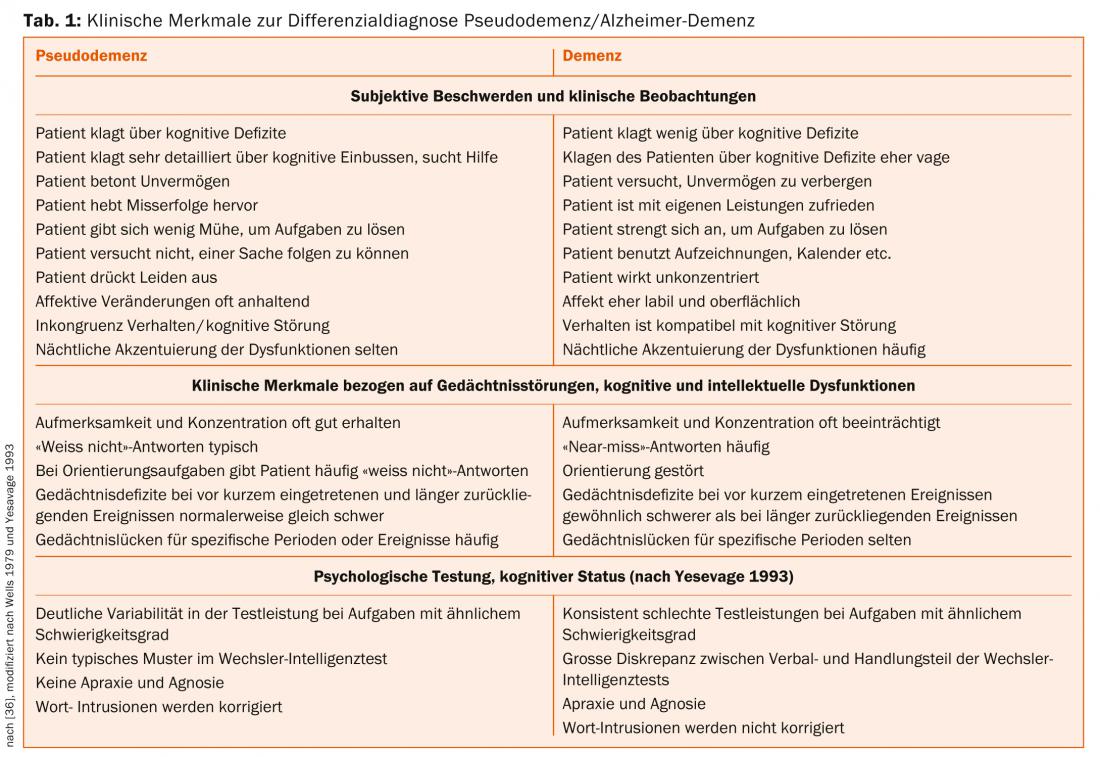

The survey of psychopathology and behavior can also provide clues for differentiating depression from dementia. Table 1 provides some clues that can differentiate between the presence of depression and dementia.

Dementia patients may also exhibit social withdrawal and apathy as well as pathological wandering, especially in the early and middle stages of dementia [21].

The gold standard for the diagnosis of dementia is currently the neuropsychological examination [22].

In Alzheimer’s dementia, deficits are present in almost all cognitive performance domains (memory, orientation, attention, language comprehension and production, visual perception).

At the onset of the disease, episodic short-term memory is particularly affected [23]. As the disease progresses, apraxia and impaired object recognition with preserved perception (agnosia) often develop. These two symptoms speak against the presence of pure depression.

In depression, neuropsychological testing procedures can also detect objectifiable cognitive deficits, with several studies reporting a relationship with depression severity [24,25].

Cognitive impairment in depression, similar to that in patients with dementia, affects free and delayed recall, recognition, short-term memory, word fluency, and language comprehension [26]. In addition, there is reduced psychomotor speed and information processing, as well as disturbances in concentration and attention [27].

A just-published paper identified seven factors that allow good differentiation between patients with major depression and dementia [28]. Patients with depression have significantly better outcomes than patients with dementia in the areas of verbal and visual attention, visual learning and memory, speech production, and executive motor functions. The difference was most pronounced in the area of verbal learning and memory functions.

In contrast, neuropsychological differentiation between patients with MCI (“mild cognitive impairment”) and depression is almost impossible [28,29].

The basis of neuropsychological testing for dementia is the CERAD test battery, which is used in all memory clinics [22].

Because of the reported relationship between the severity of depression and the intensity of cognitive impairment, neuropsychological testing is not recommended in patients with marked depressive symptomatology or is recommended only after depressive symptomatology has resolved. However, antidepressant therapy does not always lead to remission of the cognitive disorder even in patients with depression [13], so that a “diagnosis ex juvantibus” can be made in only some of the patients.

Additional diagnostics: Structural imaging (CT or MRI), which is mandatory in the context of dementia diagnostics, can provide further clues to the differential diagnosis of dementia or depression (vascular change, brain volume reduction, hippocampal atrophy). However, these findings can at best support or cast doubt on the suspected clinical diagnosis previously made; a diagnosis based on imaging alone is not possible.

If the diagnosis is still unclear – after all diagnostic measures have been carried out as part of the basic diagnosis of dementia – there is also the option of functional imaging using emission tomography (SPECT or PET). PET examinations have high sensitivity (92-96%) and specificity (over 95%) against non-demented patients [30]. According to the S3 guideline of the German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Neurology (DGPPN), FGD-PET and HMPAO-SPECT [31] can be used to clarify the diagnosis of dementia in unclear cases (recommendation grade A, S3 guideline DGPPN). However, regular use is not recommended; moreover, these examinations are not usually paid for by health insurance companies in Switzerland.

For the assessment of progressive neurodegeneration and the course of therapy in AD as well as for the possible evaluation of depression, volume measurement of the hippocampus and other cortical areas represents a promising method [32], which, however, has so far been reserved for only a few specialized centers and whose clinical utility still needs to be evaluated.

In diagnostically unclear cases and therapy resistance, a CSF examination should first be performed according to the S3 guideline to exclude an inflammatory genesis and with regard to the parameters amyloid-β-peptides, tau and phospho-tau.

Finally, the importance of sleep medicine diagnostics should be mentioned. Both depression and dementia are often accompanied by sleep disturbances, which per se may be responsible for cognitive impairment and therefore need to be treated. In addition, dementias are increasingly associated with defined sleep disorders, such as REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) and sleep apnea (vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia) [33]. A special syndrome is “sun-downing”, which is characterized by states of confusion and wandering in the late afternoon hours and often occurs in dementia [34].

However, these tests can only provide clues as to whether depression or dementia is more likely to be present. Ultimately, the further clinical course is decisive, which must therefore always be well monitored in the awareness that dementia may be behind the depressive symptomatology with cognitive disorders.

PD Dr. med. Dr. phil. Ulrich-Michael Hemmeter

Literature:

- Swiss Alzheimer’s Association. Society and Politics: www.alz.ch/index.php/gesellschaft-politik.html; 2012a [accessed 22.8.2012].

- Beekman AT, CopelandJR, PrinceMJ: Review of community prevalence of depression inlater life. The British Journal of Psychiatry 1999; 174: 307-311.

- Alexopoulos GS: Depression in the elderly. Lancet 2005; 365(9475): 1961-1970.

- Hammami S, et al: Screening for depression in an elderly population living at home. Interest of the Mini-Geriatric Depression Scale. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2012; Jun 18.

- Jongenelis K, et al: Prevalence and risk indicators of depression in elderly nursing home patients: the AGED study. Journal of Affective Disorders 2004; 83: 135-142.

- Steffens DC, et al: Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population the cache county study FREE. Archives of General Psychiatry 2000; 57(6): 601-607.

- Swiss Alzheimer’s Association/if applicable. Bern. Living with Dementia in Switzerland – Key Data2 – Current Care Study commissioned by the Swiss Alzheimer’s Association. Bern 2004.

- Enache D, Winblad B, Aarsland D: Depression in dementia: epidemiology, mechanisms, and treatment. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2011 Nov; 24(6): 461-472.

- Karttunen K, et al: ALSOVA study group: Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in patients with very mild and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011 May; 26(5): 473-482.

- Castilla-Puentes RC, Habeych ME: Subtypes of depression among patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Alzheimers Dement 2010 Jan; 6(1): 63-69.

- Ballard C, et al: Anxiety, depression and psychosis in vascular dementia: prevalence and associations. J Affect Disord 2000 Aug; 59(2): 97-106.

- Salloway S, et al: MRI and neuropsychological differences in early- and late-life-onset geriatric depression. Neurology 1996 Jun; 46(6): 1567-1574.

- Reppermund S, et al: Cognitive impairment in unipolar depression is persistent and non-specific: further evidence for the final common pathway disorder hypothesis. Psychol Med 2009 Apr; 39(4): 603-614.

- Sheline YI: Depression and the hippocampus: cause or effect? Biol Psychiatry 2011 Aug 15; 70(4): 308-309.

- Byers AL, Yaffe K: Depression and risk of developing dementia. Nat Rev Neurol 2011 May 3; 7(6): 323-331.

- Byers AL, et al: Dysthymia and depression increase risk of dementia and mortality among older veterans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012 Aug; 20(8): 664-672.

- Saczynski JS, et al: Depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: the Framingham Heart Study. Neurology 2010 Jul 6; 75(1): 35-41.

- Dotson VM, Beydoun MA, Zonderman AB: Recurrent depressive symptoms and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 2010 Jul 6; 75(1): 27-34.

- Savaskan E, et al: Recommendations for the management of psychological and behavioral symptoms in dementia. Praxis (Bern 1994) 2014 Jan 29; 103(3): 135-148.

- Reifler B, Larson E, Harley R: Co-existence of cognitive impairment and depression in geriatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 1982; 139: 623-626.

- Reisberg B, et al: Stage Specific Incidence of Potentially Remediable Behavioral Symptoms in Aging and Alzheimer Disease. Bulletin of Clinical Neurosciences 1989; 54: 95-112.

- Ehrensperger MM, et al: Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease with a total score of the German CERAD. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2010 Sep; 16(5): 910-920.

- Almkvist O: Neuropsychological features of early Alzheimer’s disease: preclinical and clinical stages. Acta neurologica Scandinavica 1996; 165 (suppl.): 63-71.

- Cohen RM, et al: Effort and cognition in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982 May; 39(5): 593-597.

- Sternberg DE, Jarvik ME: Memory functions in depression. Improvement with antidepressant medication. Archives of General Psychiatry 1976; 33: 219-224.

- Brown RG., et al: Cognitive function in depression: its relationship to the presence and severity of intellectual decline. Psychological Medicine 1994; 24: 829-847.

- Veiel HO: Preliminary profile of neuropsychological deficits associated with major depression. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1997 Aug; 19(4): 587-603.

- Beck IR, et al: Establishing robust cognitive dimensions for characterization and differentiation of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, frontotemporal dementia and depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013 Nov 14. doi: 10.1002/gps.4045. [Epub ahead of print].

- Zihl J, et al: Neuropsychological profiles in MCI and in depression: differential cognitive dysfunction patterns or similar final common pathway disorder? J Psychiatr Res 2010 Jul; 44(10): 647-654.

- Vandenberghe R, et al: Amyloid PET in clinical practice: Its place in the multidimensional space of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage Clin 2013 Apr 6; 2: 497-511.

- Stoppe G, et al: E 99mTc-HMPAO-SPECT in the diagnosis of senile dementia of Alzheimer’s type – a study under clinical routine conditions. J Neural Transm Gen Sect 1995; 99(1-3): 195-211.

- Lebedev AV, et al: Cortical changes associated with depression and antidepressant use in Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia: an MRI surface-based morphometric study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014 Jan; 22(1): 4-13.e1.

- Bliwise DL: Sleep disorders in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Clin Cornerstone. 2004; 6 Suppl 1A: S16-28.

- Khachiyants N, et al: Sundown syndrome in persons with dementia: an update. Psychiatry Investig 2011 Dec; 8(4): 275-287.

- Jessen, et al: S3-Leitlinie Demenz, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN) 2009. www.dggpp.de/documents/s3-leitlinie-demenz-kf.pdf

- Dykierek P: Multimodal diagnostics in Alzheimer’s dementia and old-age depression, Psychology, theory and research, S. Roderer Verlag Regensburg, 1998.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2014; 12(3): 8-12.