Inflammatory brain diseases are caused by bacteria, fungi, parasites, virus or prions and present with a wide variety of symptoms, many of which can also be caused by non-infectious brain diseases. Fortunately, the informative value of neuroradiological examinations, especially in the field of MR technology, has continued to develop in recent years. Thus, a variety of relatively specific imaging signs in infectious diseases have been described today, making neuroradiology seminal in the clinical workup.

In the following article, some typical core findings in the cross-sectional diagnosis of cerebral parenchymal infections are illustrated for the different pathogen types.

Bacterial brain abscesses

Half of all brain abscesses arise per continuitatem from adjacent structures, then usually on the floor of sinusitis or otitis. A quarter of all brain abscesses develop hematogenously, e.g., on the floor of a bacterial endocarditis or a purulent pneumonia. Less than 50% of patients experience the classic triad of fever, headache, and focal neurologic deficits.

Bacterial brain abscesses develop from cerebritis. This is characterized by blurred hypodense lesions on CT or hyperintense changes on T2-weighted MR image with little or sparse contrast uptake (in the first few days). As the disease progresses, a brain abscess develops, which must be differentiated from other contrast-enhancing lesions, primarily high-grade gliomas and metastases.

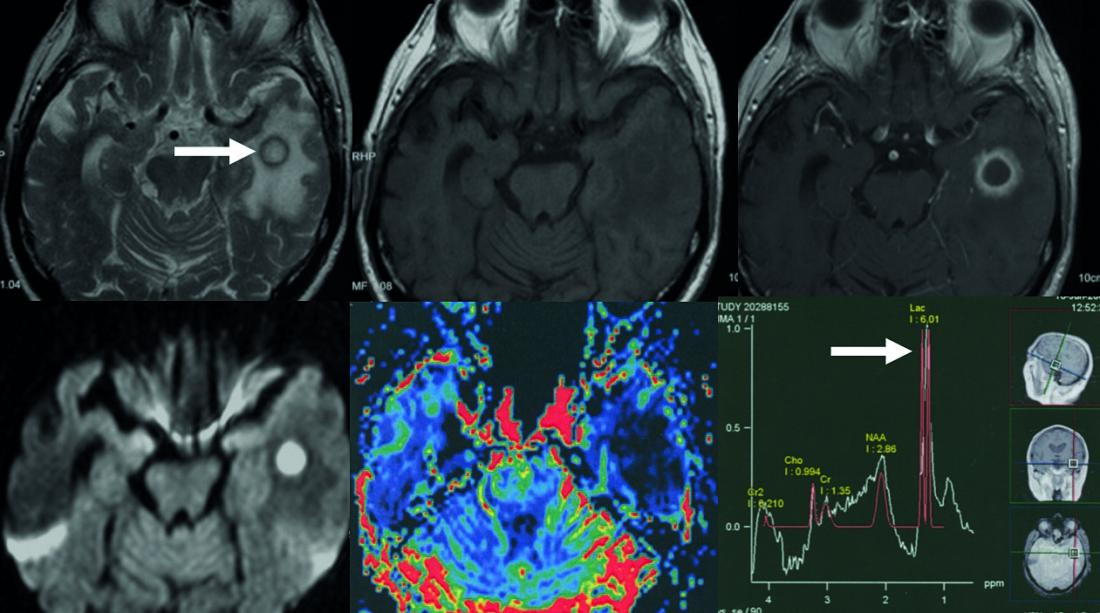

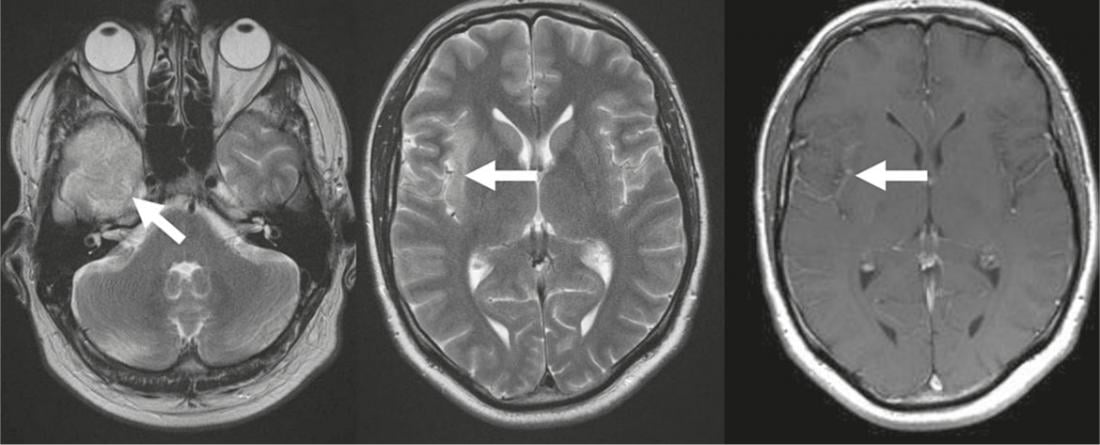

An abscess is typically indicated by a hypointense abscess margin on T2-weighted images (Fig. 1). Free radicals produced by macrophages in the periphery of the abscess are held responsible for this. These are strongly paramagnetic. In contrast to tumors, this abscess border is usually smooth on the outside. Restriction of diffusion with negative ADC values in the cystic portion is relatively specific within annular contrast-enhancing space, but can also be observed in metastases (primarily bronchial and breast carcinoma). On perfusion MRI examination, regional cerebral blood volume is only slightly increased, if at all, in the area of the contrast-enhancing rim, whereas there is often a marked increase in tumors. MR spectroscopically, lactate elevation is usually present. With a differentiated analysis, possible indications of the pathogen type (aerobic vs. anaerobic) can also be obtained (Pal et al.). There is no elevation of the choline to N-acetylaspartate ratio in the solid portion of the mass, which is typical in tumors.

Fig. 1: Temporal bacterial brain abscess

Top row: annular mass with T2-w hypointense fringe (arrow).

T1-w before and after contrast administration. The contrast agent-absorbing abscess fringe is thin and relatively smoothly bordered. Bottom row: restricted diffusion in the center of the abscess, map of relative cerebral blood volume. The abscess seam shows a decreased blood volume (color red corresponds to increased blood volume).

Neurotuberculosis

When neurotuberculosis is suspected, imaging is of critical importance because laboratory chemistry tests have limited sensitivity, results are not immediately available, and therapy should be started quickly (Gupta RK, et al).

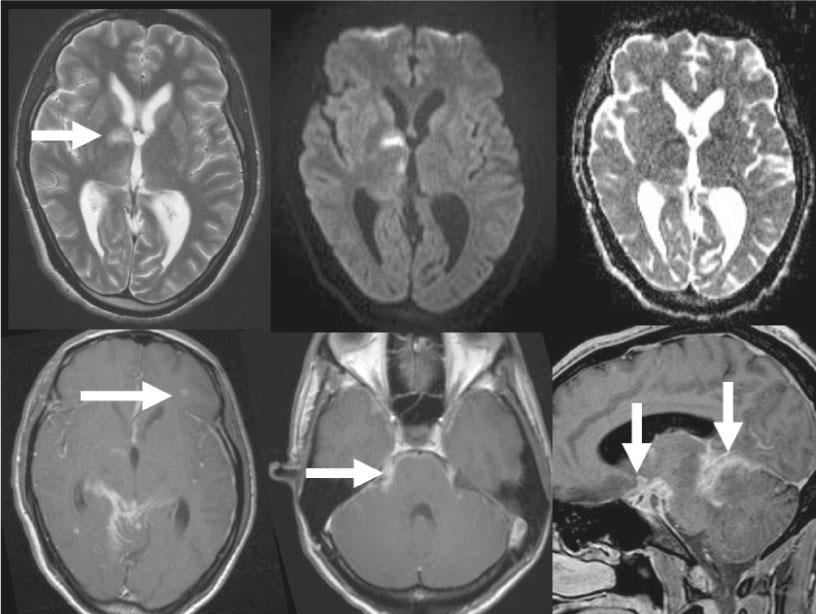

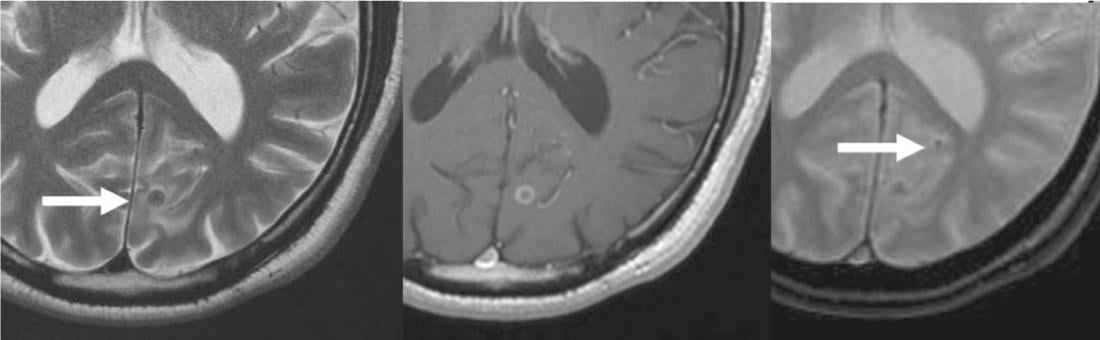

Characteristic of tuberculous meningitis is a thick exudate of the meninges of the base of the brain. This is best seen on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images (Fig. 2). Hydrocephalus is the most frequently observed complication, which is usually a communicating hydrocephalus due to impaired CSF absorption. The second major complication is cerebral infarction. These are caused by affection of the perforating basal cerebral arteries. A third complication is affection of the carinal cranial nerves, with cranial nerves II, III, IV, VI, and VII most commonly affected. Parenchymal tuberculosis is characterized by tuberculous granulomas (tuberculomas), circumscribed inflammatory lesions of mycobacteria surrounded by a granulomatous reaction. These lesions are usually located at the corticomedullary border zone, hypodense on CT and hypointense on T1-weighted native images. After contrast administration, the granulomas show either homogeneous enhancement (non-caseating granuloma) or ring enhancement (caseating granuloma). The caseating granuloma may contain fluid content (T2 hyperintense) or be solid (T2 hypointense to isointense). A tuberculous abscess may be indistinguishable from a caseating tuberculoma with a fluid center. Typically, an abscess is larger and patients are more severely ill. The differential diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis includes other infectious diseases (sarcoidosis and meningeal carcinomatosis). Tuberculomas and tubercular abscesses must be differentiated primarily from primary and secondary brain tumors and other granulomatous infectious processes.

Fig. 2: Neurotuberculosis

Top row: T2-w image, the internal CSF spaces are too wide for a 24-year-old patient, there is incipient hydrocephalus malresorptivus. Hyperintense acute infarction in the basal ganglia (arrow), restricted diffusion on DWI images and further acute thalamic infarction on the right, decreased ADC values. Contrast-enhanced T1-w images. Bottom row: Multiple tuberculomas, the largest is on the left frontal side (arrow). Basal meningeal contrast image, good overview on sagittal image, contrast image along trigeminal nerve bilaterally (arrow).

Viral encephalitis

Over 100 viruses are known to cause encephalitis or meningoencephalitis. Radiologic findings in adult viral encephalitis are nonspecific with focal or diffuse cerebral edema in the acute phase and focal atrophy with gliosis in the chronic stage.

The exception is herpes simplex virus type 1 encephalitis, which has a classic pattern of involvement of the limbic system. After primary infection, the virus spreads retrogradely to the olfactory bulb or along a branch of the trigeminal nerve into the ganglion of Gasser. Reactivation of latent infection is favored by immunosuppression. Encephalitis typically presents as focal brain edema in the medial and inferior temporal lobes with extension to the insula and cingulate gyrus, leaving the putamen exposed (Fig. 3). In most cases, cytotoxic cerebral edema is initially present. Meningeal and gyral contrast uptake occurs only as the disease progresses.

Petechial hemorrhages, typically at the cortico-medullary junction, are more commonly observed.

HIV encephalitis is characterized by mostly symmetric and areal confluent focal T2-w hyperintense white matter lesions, usually leaving out the cortex and U-fibers (short association fibers between adjacent gyri). In the course, a slowly progressive brain volume reduction occurs.

Progressive multifocal encephalopathy is caused by JC virus (Papova virus). Again, focal hyperintensities occur subcortically, typically in the posterior centrum semiovale, with the lower cortex layers and subcortical U-fibers relatively commonly affected. This viral infection is the most common opportunistic viral infection of the CNS in AIDS. In addition, it is important to recognize this viral infection as a complication, especially in the context of MS therapy with natalizumab.

Fig. 3: Herpes encephalitis

T2-w images show temporal (arrow) hyperintense cerebral edema with spread to the insular cortex (arrow); the putamen is not affected. T1-w after

Contrast administration low gyral contrast uptake (arrow).

Parasitic brain diseases

The diagnosis of parasitic inflammatory diseases is usually made from a combination of patient history, including vacation visits, clinical findings, serologic tests, and neurologic findings.

The most common parasitic CNS disease worldwide is neurocysticercosis. The causative agent is the larval form of the pork tapeworm Taenia solium, with humans acting as intermediate hosts. Different stages of parenchymal involvement are distinguished (simple vesicle, colloid vesicle, granular nodule). The final stage is the appearance of calcified nodules, which are best detected as small calcifications on CT or MRI on T2*-weighted images (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Neurocysticercosis

T2-w hypointense lesion (arrow) occipital corticomedullary, with annular

Contrast image on T1-w images (center), corresponding to third-stage neurocysticercosis. A second small calcified lesion is best differentiated on T2*-w images (arrow in right image), corresponding to a stage four lesion.

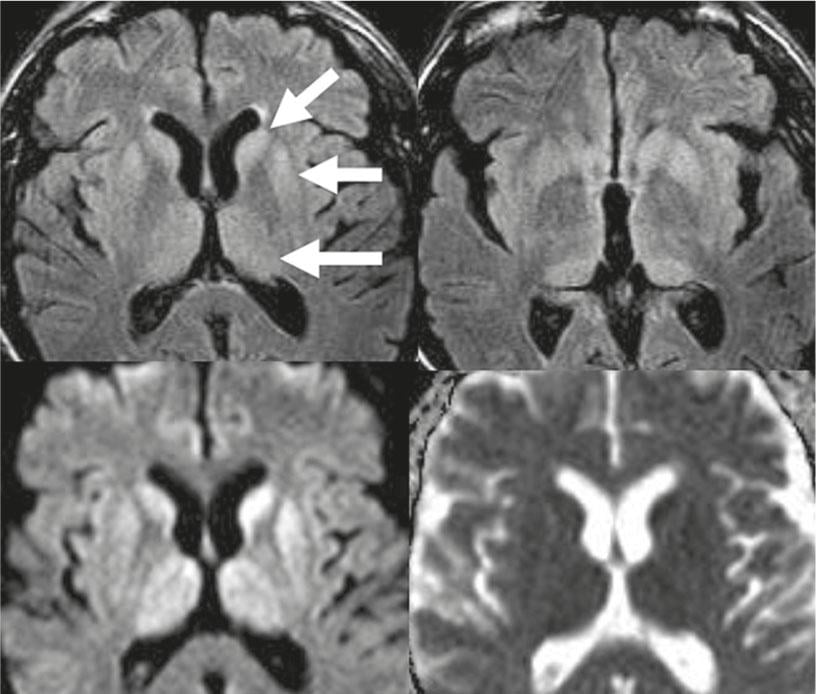

Prions

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is caused by prions. Clinically, the infection is characterized by rapidly progressive dementia and cerebellar ataxia. In addition to EEG and CSF findings, MRI plays an important role. Here, signal hyperintensities FLAIR and T2-weighted are characteristically found in the striatum and cortex and thalamus (Fig. 5). In the variant form of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, the changes are particularly pronounced in the pulvinar thalami (pulvinar sign). Typically, the changes in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease are accompanied by diffusion restriction.

Fig. 5: Creutzfeld-Jakob disease

Top row: on FLAIR-w images, pronounced symmetrical hyperintensities of the caput nucleus caudatus, putamen, and thalamus (arrows). Bottom row: these lesions show restricted diffusion with decreased ADC values.

Literature list at the publisher