Reconstructive procedures strive to restore functional lymphatic drainage. Lymphatic surgery is indicated in patients in whom conservative therapy does not result in adequate control of the disease. Principles of autologous vascularized lymph node transplantation and classification of its efficacy.

Complex physical decongestive therapy (CPD) is the gold standard in the treatment of patients suffering from chronic lymphedema. The aim of conservative therapy is to achieve a “restitutio ad integrum” in the best case. Most often, conservative therapy helps to prevent progression of the disease with recurrent infections (erysipelas). This sustained therapy is very costly for patients and therapists and often has to be performed for life [1]. Thus, surgical approaches to the treatment of chronic lymphedema were intensively sought in the early part of the last century. A basic distinction can be made between resection and reconstruction procedures. Resectioning procedures include radical excision of the diseased skin/subcutaneous fat or liposuction-based tissue reduction with concomitant compression therapy [2]. Reconstructive procedures, on the other hand, aim to restore functional lymphatic drainage. The correct indication is crucial: In principle, all degrees of lymphedema severity can be treated surgically. Of course, however, a careful weighing of benefits and risks must be made. Lymphatic surgery is indicated only in patients in whom conservative therapy does not result in adequate control of the disease. Kung et al. have recently published an algorithm for the indication of the different surgical therapy options [3]. Of importance is whether, firstly, intact lymphatic vessels are present and, secondly, whether patients have undergone lymphadenectomy and/or pre-irradiation. Depending on the constellation, various resecting or reconstructive procedures can then be used individually or in combination (see also the article “Lymphovenous anastomoses and resecting procedures” in this training focus.

Spectrum of reconstructive lymphatic surgery

Functional restoration of the lymphatic system can be achieved by various methods.

So can

- lymphatic vessels themselves can be transplanted microsurgically (lymphatic vessel transplantation) [4],

- lymphatic vessels are connected to veins by microsurgery (lymphovenous anastomosis) [5].

- or fat-lymph node packages (with or without skin island) with afferent and efferent lymphatic vessels (vascularized lymph node transplantation [6]) can be transplanted as a functional unit.

All methods require microsurgical training, lymphatic vessel transplantation and lymphovenous anastomosis even require supermicrosurgical knowledge and instruments, since these techniques sometimes require lymphatic vessels with a diameter of approximately 0.3 mm to be anastomosed. Vascularized lymph node transplantation, its potential applications, and expected outcomes are presented below.

The autologous vascularized lymph node transplantation – basics.

In vascularized lymph node transplantation, a fat-lymph node package (“composite” flap) is lifted from an expendable donor site with a supplying vascular pedicle and microvascularly connected to the lymphedema-affected limb. Consequently, only the blood vessels (artery and vein) of the fat lymph node flap are connected to the recipient site. The lymphatic vessels of the graft must spontaneously connect in the recipient tissue after transplantation. In this process, lymphatic vessel formation and functional integration of lymph nodes are stimulated via growth factors such as VEGF-C and VEGF-D [7,8]. Two scientific theories exist regarding the efficacy of lymph node transplantation [9]. The “lymphatic wick theory” states that the efferent lymphatic vessels of the recipient site connect to the afferent lymphatic vessels of the transplanted lymph nodes and the lymph can drain via the efferent lymphatics of the graft. The so-called “lymphatic pump theory” postulates intrinsic lymphovenous anastomoses in the transplanted lymph nodes with at least partial outflow of lymph via the vascular system [10].

Donor sites and morbidity

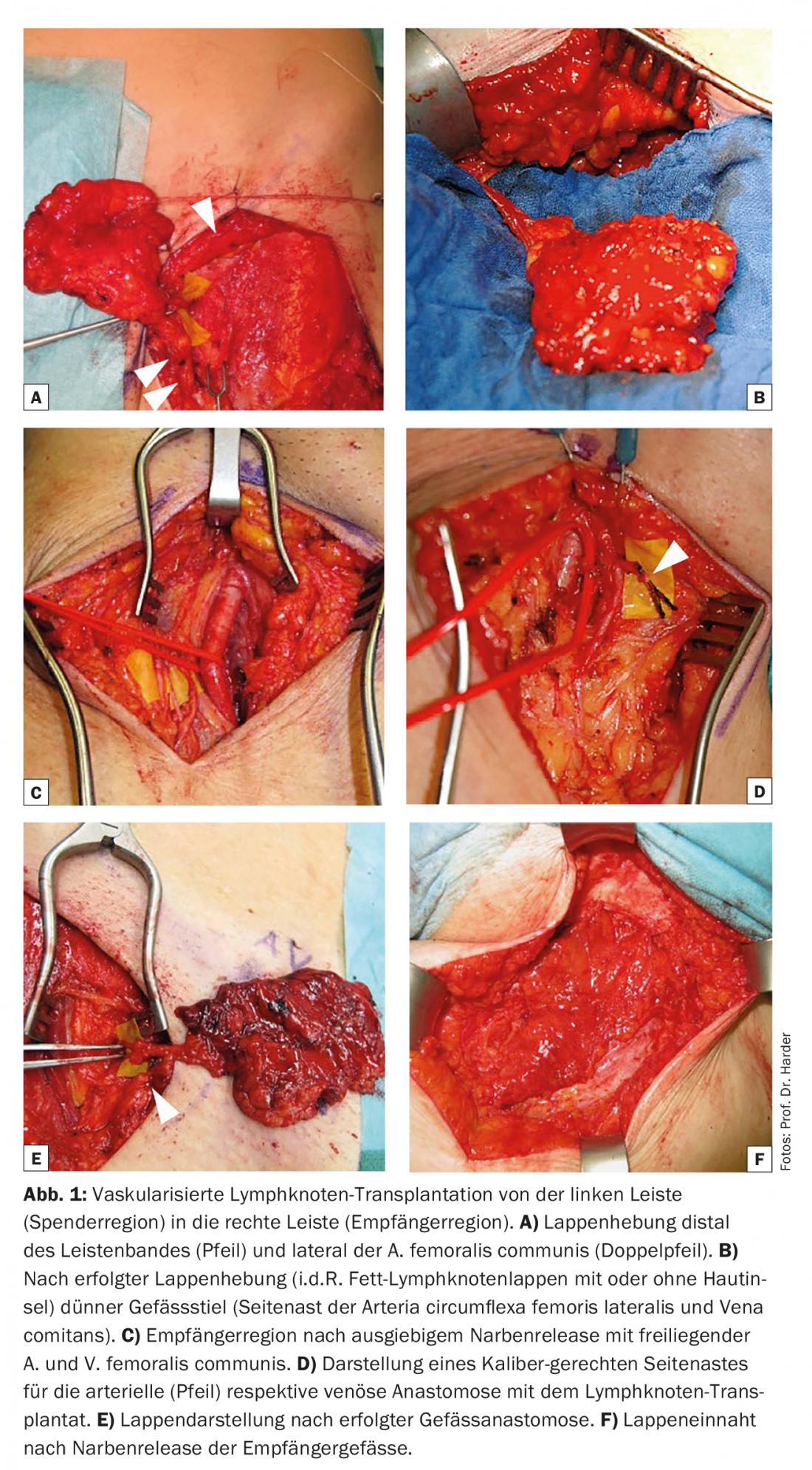

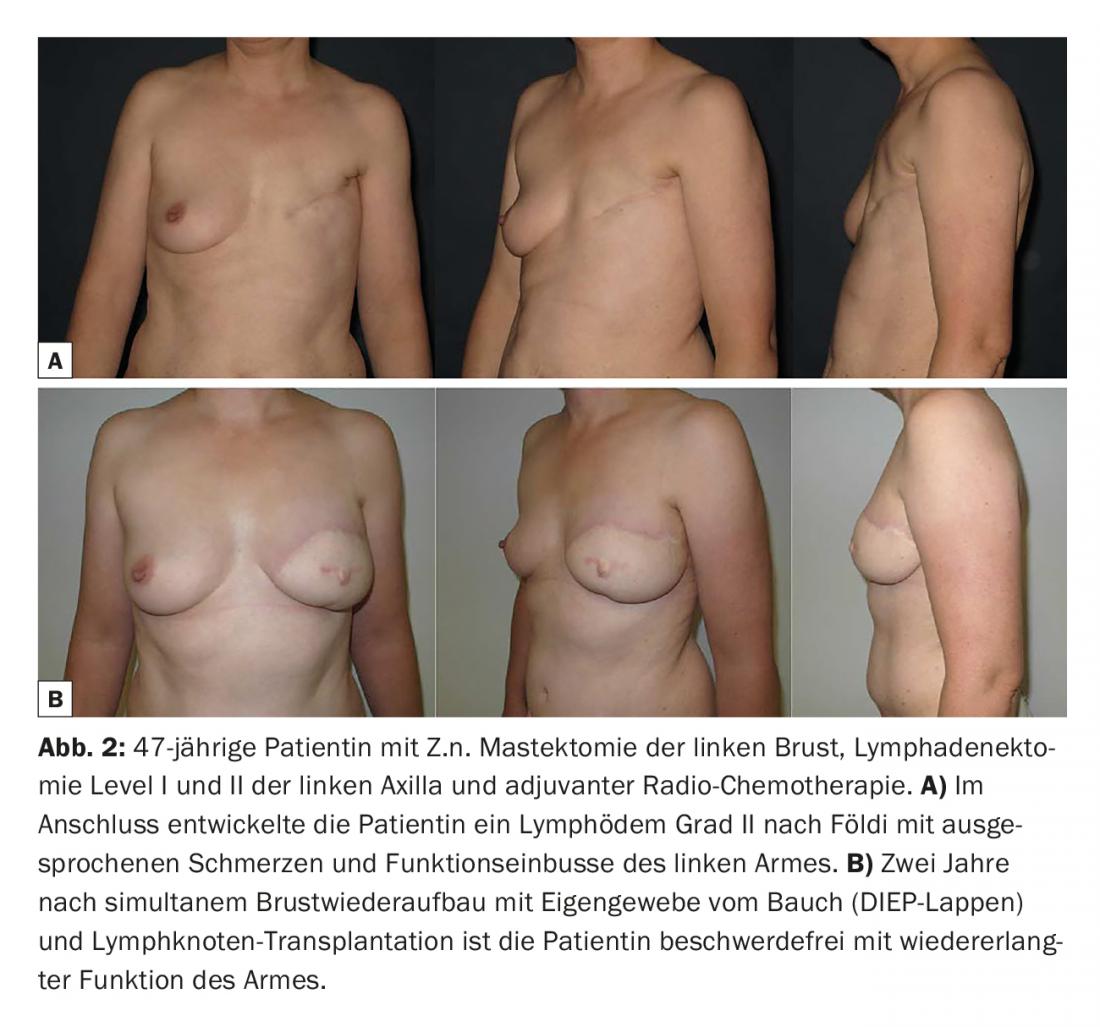

The donor site most commonly used for lymph node transplantation is the groin (Fig. 1) . The craniolateral lymph nodes are pedicled at the vasa circumflexa iliaca superficialia and are then deposited. Because this lymph node bundle predominantly drains the lower abdomen as well as the gluteal region, iatrogenic and functionally relevant lymphedema is very rare [9,11]. Furthermore, the lateral inguinal region is cosmetically favorable and characterized by a lower risk of severe nerve lesions than other donor sites. Nevertheless, the risk of lymphatic dysfunction at the lifting site is not negligible [12] and must be addressed in detail with patients preoperatively. A recent review put the total complication rate at the inguinal lifting site at ~10%, of which iatrogenic lymphedema was present in 1.5% of cases [13]. Alternatively, lymph node flaps can be lifted axillary (level I), submental, supraclavicular, or omental (open or laparoscopic) for transplantation. The inguinal lymph node lifting site allows simultaneous lymph node transplantation into the axilla and reconstruction of the breast with abdominal autologous tissue (microvascular DIEP or msTRAM flap; Fig. 2).

Vascularized lymph node transplantation is a more invasive procedure than lymphatic vessel transplants or lymphovenous anastomoses and, importantly for patients, has a higher risk of iatrogenic lymphatic dysfunction with subsequent formation of lymphatic fistulas or lymphedema at the donor site.

Meaning of the scar release

Lymphedema, which occurs in our latitudes, is usually associated with onco-surgical therapy. This secondary lymphedema is thus a consequence of a previously performed lymphadenectomy and/or irradiation of the lymph node region with extensive scarring. Experimental studies show that this tissue fibrosis is a very significant antagonist of lymphatic regeneration [14]. Accordingly, treatment of chronic lymphedema by vascularized lymph node graft can be successful only if the indurated scar tissue is radically resected (scar release). This is the only way to enable the transplanted lymphatic tissue to form lympho-lymphatic connections in the recipient tissue, which can subsequently contribute to lymphatic drainage.

Efficacy of lymph node transplantation

Lymphedema monitoring after lymph node transplantation is essential for the evaluation of the procedure. Unfortunately, a wide range of different measurement methods can be found in the literature. Thus, various indirect or direct volumetry methods (including circumferential measurement, water displacement, or laser scan), erysipelas rate detection, or imaging techniques (lymphoscintigraphy, MR lymphography, ICG lymphography) are used in very different ways. As a result of this heterogeneity, the few existing reviews on the subject are of limited value, and only meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials will be able to conclusively assess the long-term outcomes of lymph node transplantation. Thus, based on current knowledge, we are largely reliant on case series to demonstrate the efficacy of the procedure. Recent studies show that both treated limb volumes and erysipelas rates can be significantly reduced by lymph node transplantation [15,16]. In a personal series (Harder Y, Müller D, Machens HG) of now about 90 lymph node transplants (68 women; 14 men; 5 bilateral and 3 serial transplants), we could show the following: Reduction of weather sensitivity and infection rate: 66%; Improvement of limb function: 50%; Reduction of compression degree of compression garment: 44%; Reduction of lymphatic drainage frequency: 11%; Discontinuation of CPE: 22%; Reduction of edema volume after four years: 38% (for case example see. Figures 3 and 4). These results are in line with a first randomized study demonstrating that in breast cancer-associated lymphedema, the combination of lymph node transplantation/KPE is superior to CPE alone in terms of reduction of edema and erysipelas rate as well as improved limb function [17].

Conclusion

Vascularized lymph node transplantation is a promising therapeutic option and can successfully restore lymphatic drainage in patients with chronic lymphedema. When combined with time-honored conservative compression measures, lymph node transplantation can result in considerable edema reduction. However, it should be noted that the procedure is technically demanding and has some risk of iatrogenic lymphatic dysfunction with lymphatic fistulas and lymphedema at the lifting site.

Take-Home Messages

- Chronic lymphedema is an invalidating condition and can occur as a severe complication of oncosurgical treatments.

- In recent years, autologous vascularized lymph node transplantation has been increasingly used to treat severe lymphedema.

- Restoration of spontaneous (functional) lymphatic drainage with autologous tissue is a potentially curative procedure with promising initial long-term clinical results.

Literature:

- Shih YC, et al: Incidence, treatment costs, and complications of lymphedema after breast cancer among women of working age: a 2-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27: 2007-2014.

- Boyages J, et al: Liposuction for Advanced Lymphedema: A Multidisciplinary Approach for Complete Reduction of Arm and Leg Swelling. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22 (3): 1263-1270.

- Kung TA, et al: Current Concepts in the Surgical Management of Lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017; 139: 1003e-1013e.

- Baumeister RG, et al: Microsurgical lymphatic vessel transplantation. J Reconstr Microsurg 2016; 32: 34-41.

- Koshima I, et al: Supermicrosurgical lymphaticovenular anastomosis for the treatment of lymphedema in the upper extremities. J Reconstr Microsurg 2000; 16: 437-442.

- Becker C, et al: Postmastectomy lymphedema: long-term results following microsurgical lymph node transplantation. Ann Surg 2006; 243: 313-315.

- Tammela T, et al: Therapeutic differentiation and maturation of lymphatic vessels after lymph node dissection and transplantation. Nat Med 2007; 13: 1458-1466.

- Lähteenvuo M, et al: Growth factor therapy and autologous lymph node transfer in lymphedema. Circulation 2011; 123: 613-620.

- Tourani SS: Vascularized Lymph Node Transfer: A Review of the Current Evidence. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016; 137: 985-993.

- Lin CH, et al: Vascularized groin lymph node transfer using the wrist as a recipient site for management of postmastectomy upper extremity lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 123: 1265-1275.

- Viitanen TP, et al: Donor-site lymphatic function after microvascular lymph node transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012; 130: 1246-1253

- Sulo E, et al: Risk of donor-site lymphatic vessel dysfunction after microvascular lymph node transfer. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2015; 68: 551-558.

- Scaglioni MF, et al: Comprehensive review of vascularized lymph node transfers for lymphedema: outcomes and complications. Microsurgery 2016, in press. doi: 10.1002/micr.30079.

- Avraham T, et al: Radiation therapy causes loss of dermal lymphatic vessels and interferes with lymphatic function by TGF-beta1-mediated tissue fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010; 299: C589-605.

- Ciudad P, et al: Comparison of long-term clinical outcomes among different vascularized lymph node transfers: 6-year experience of a single center’s approach to the treatment of lymphedema. J Surg Oncol 2017, in press. doi: 10.1002/jso.24730.

- Nguyen AT, et al: Long-term outcomes of the minimally invasive free vascularized omental lymphatic flap for the treatment of lymphedema. J Surg Oncol 2017; 115: 84-89.

- Dionyssiou D, et al: A randomized control study of treating secondary stage II breast cancer-related lymphoedema with free lymph node transfer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016; 156: 73-79.

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(5): 16-20