Burn depth and burn area, as well as concomitant diseases and injuries, determine the indication for transfer to a severe burn center. Burns up to grade 2a are treated conservatively. The principles of modern moist wound care are to be applied. Hydrofiber dressings in particular have proven effective. Burns of grade 2b and above are usually treated surgically. Scars must be cared for and monitored throughout life with appropriate externals. In the case of extensive burns or burns to exposed parts of the body, extensive therapy in the form of psychological support and gradual social reintegration is necessary.

First, a few words about the structure of the skin. The epifascial skin soft tissue mantle consists of epidermis, dermis and subcutis. The fascia separates the skin soft tissue mantle from subfascial structures such as musculature, bones, and possibly viscera. The avascular epidermis renews approximately every 28 days in healthy individuals. Injuries that do not cross the epidermis therefore heal without scarring. In addition to the keratinocytes, the melanocytes are an important component of the epidermis, which protect the skin from UV radiation through the production of melanin. The basement membrane separates the epidermis from the underlying dermis. Numerous cell types and skin appendages are found there, which significantly shape the character of the skin’s soft tissue mantle – e.g. sweat and sebaceous glands, whose secretions nourish the skin as well as provide a barrier against bacteria due to the acidic pH value. The subcutis varies in thickness depending on the region of the body and acts as a buffer layer.

Epidemiology and etiology

In our Western world, most burn injuries occur in the home environment. The most common causes in adults are flame burns, followed by hot liquid injuries, explosions, and lastly, electrical injuries. Accidental scalds are very common in children. Think spilled water or a leaking hot water bottle. Furthermore, child abuse must always be considered in the case of children.

Initial therapy

In burn patients, the body’s own thermoregulation is disturbed. Therefore, aggressive cooling, e.g. with cooling units, is no longer recommended. There is a risk of additional damage from frostbite. Cleaning or application of externals or removal of blisters should also be refrained from. Sterile draping of wounds and expeditious transport to an appropriate medical facility are key. Depending on the extent of the burn, further measures such as pain therapy and fluid substitution must be initiated. If there is additional inhalation trauma with progressive pulmonary insufficiency, intubation is indicated.

Clinical image

In order to be able to assess the extent of the burn and take the correct measures, both the calculation of the burned body surface and a depth assessment are necessary.

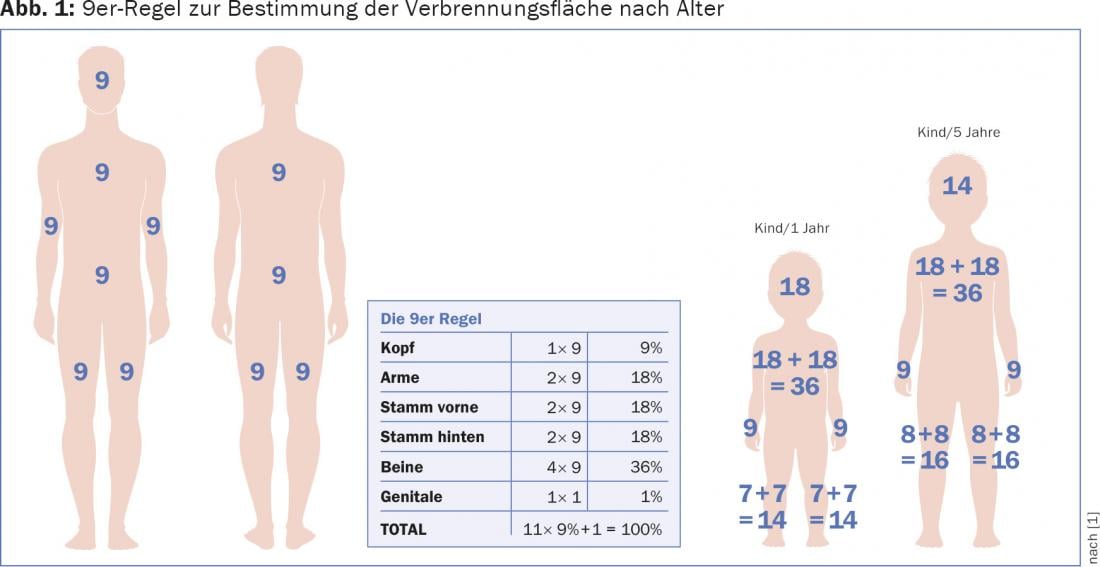

While the burned body surface area can still be determined relatively well by means of the rule of 9 (Fig. 1) , it is not easy to distinguish between different burn depths. In particular, the distinction between grade 2a and 2b is challenging. However, this distinction is eminently important because it has crucial therapeutic consequences. A type 2a burn can usually be managed conservatively, while a type 2b burn usually requires surgical treatment.

Depth expansion

The depth expansion results from the acting temperature and the exposure time. Grade 1 and grade 2a burns are referred to as superficial burns. Grade 2b, 3 and 4 are classified as deep burns.

To differentiate between deep and superficial combustion, the so-called compressor test is helpful. A sterile compress is applied to the wound. If the patient feels pain and no body hair is found on the compress, a superficial injury can be assumed. In contrast, absence of pain or remaining body hair on the compress is considered a deep burn.

Another clinical test is the spatula test. A sterile spatula is pressed onto the wound bed. If recapillarization occurs, a superficial injury is present (spatula test positive) – if there is no recapillarization, a deep injury must be assumed (spatula test negative).

The color of the tissue also helps distinguish between superficial and deep burns. Typically, superficial burns appear red and are moist. Deep burn wounds tend to be yellowish-brownish to whitish and dry.

Combustion degrees

Grade 1: Painful redness of the skin, superficial burn with damage to the epidermis at temperatures above 45°C. Clinical example: sunburn.

Grade 2a: Superficial burn, damage to epidermis and superficial layers of dermis. Skin appendages intact, painful blistering. Moist wound bed. Conservative to manage.

Grade 2b: Deep burn, painful blistering, dry wound bed. Usually surgical therapy, scarring.

Grade 3: Deep damage to the skin with destruction of the subcutis. Usually painless due to nerve destruction. Gray-white, leathery, dry wound base.

Grade 4: Wound with charring. The defect extends into subfascial structures. Intensive medical care required. Extensive plastic defect coverage necessary. Amputation if necessary (Fig. 2).

Surface area

The areal extent of the injured skin is expressed as a percentage of the body surface area (%KOF). Among other things, Wallace’s Rule of 9 is used. For children, this is modified due to the different body proportions. The palm rule states that the palm of the injured person’s hand is equal to 1% of his body surface. The determined surface area is the basis for calculating the fluid requirement as well as an important criterion for determining whether the patient needs to be transferred to a burn center.

Criteria for transfer to a burn center

Numerous criteria necessitate transfer to a burn center. Factors such as localization of the burn, extent of the burn (depth and area), and concomitant diseases or injuries play an important role. Severely burned patients have life-threatening illnesses. Shock and the threat of sepsis make intensive medical treatment unavoidable. Indications for transfer to a burn center include:

- Suspicion of inhalation trauma

- Current violations

- Very young or elderly patients (<8 years,

- >60 years)

- Burns on the face/neck, hands, feet, anogenital region, armpits, in the area of the large joints

- >20% second degree burned body surface

- >10% third degree burned body surface area

- Burns of 10% or more of body surface area in children.

Therapy

The decision as to whether the patient requires outpatient, inpatient, conservative or surgical therapy depends on various factors and often cannot be made with certainty at the outset.

First-degree burns do not require inpatient therapy unless there are other concomitant injuries or diseases. 2a-grade burns usually do not require surgical treatment. There, a contemporary moist wound therapy is indicated. Patients with burns up to 5% KOF can be managed as outpatients.

Sufficient analgesic treatment and clarification of the tetanus status must not be forgotten.

Conservative therapy: A large number of dressings are now available for the treatment of grade 2a burns. The goal is phase-adapted moist wound treatment. Among other things, antiseptic wound gels (e.g. octenidine, polihexanide), alginates, foam dressings or hydrofiber with or without added silver are used (Fig. 3) . With a few exceptions, these new dressing materials make daily dressing changes unnecessary.

Surgical therapy: Burns of grade 2b or higher should be treated surgically. In this procedure, necrotic tissue is surgically removed. This deprives the bacteria of the nutritional basis and the opportunity to retreat and counteracts infections and possible sepsis. Depending on the depth of the burn and the localization, different coverage methods are available. Mesh split-thickness skin grafting should be mentioned in this context. For cosmetic reasons and due to the tendency to shrinkage, it is not used on the face, hands, feet and oversized joints. Alloplastic skin substitutes such as Suprathel® and Matriderm® are also used, as are xenografts for large burns. Other coverage procedures include skin expansion techniques, e.g. according to Meek. An additional option is autologous skin replacement using keratinocytes.

Aftercare

Treating the burn wound itself is not the only challenge. The patient in itself is not infrequently severely traumatized. This requires psychological care and social reintegration measures. Furthermore, physiotherapy and occupational therapy are necessary to prevent contractures. Custom compression garments counteract scarring and should be worn for six months. Depending on the severity of the injury, the skin may require lifelong care. Sebaceous and sweat glands that are no longer present cause the skin to dry out and are unable to establish a protective acid mantle. If melanocytes are no longer present, the scar is exposed to sunlight without protection. Interval scarring carcinomas are not uncommon. The scar, as an expression of inferior replacement tissue, therefore requires lifelong care and attention.

Literature:

- Pallua N, Low JFA: Thermal, electrical, and chemical injuries. In: Berger A, Hierner R (Eds.): Plastic Surgery – Fundamentals, Principles, Techniques. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Tokyo 2003.

Further reading:

- Achauer BM, Sood R: Burn surgery. Saunders, Philadelphia 2006.

- Barret-Nerin JP, Herndon DN: Principles and practice of burn surgery. 1st ed. CRC Press 2004.

- Cuttle L, et al: The optimal duration and delay of first aid treatment for deep partial thickness burn injuries. Burns 2010; 36(5): 673-679.

- Herndon DN: Total burn care. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia 2012.

- Hettiaratchy S, Dziewulski P: ABC of burns: pathophysiology and types of burns. BMJ 2004; 328(7453): 1427-1429.

- Jackson DM: The diagnosis of the depth of burning. Br J Surg 1953; 40(164): 588-596.

- Jeschke MG, et al: Handbook of burns. Vol. 1. Springer, Heidelberg 2012.

- Kamolz LP, Herndon DN, Jeschke MG: Burns. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York 2009.

- Latarjet L: The management of pain associated with dressing changes in patients with burns. EWMA Journal 2002; 2(2): 5-9.

- Richardson, P Mustard L: The management of pain in the burns unit. Burns 2009; 35(7): 921-936.

- Tobalem M, et al: First-aid with warm water delays burn progression and increases skin survival. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2013; 66(2): 260-266.

- Vogt MP: Practice of plastic surgery. Springer, Berlin 2011.

- Wolf SE, Herndon DN: Handbook of burn care (Vademecum). Landes Bioscience, Austin 1999.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2015; 25(5): 11-15