The newer therapeutics for chronic hepatitis C are now available to all infected patients regardless of fibrosis stage. DAA combinations make the disease curable in over 95% of cases.

According to WHO estimates, about 71 million people worldwide are infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) and about 400,000 people die each year as a result of hepatitis C virus infection. Therefore, the elimination of hepatitis B and C virus infections as life-threatening conditions by 2030 (by reducing the rate of new infections by 90% and mortality by 65%) has been formulated as one of the major medical goals for the coming years [1,2].

According to estimates, about 40,000 people in Switzerland are affected by the hepatitis C virus, which corresponds to about 0.5% of the population, although a considerable number of undiagnosed infected persons must still be taken into account [3].

Transmission and virus buildup

The virus is transmitted parenterally, nowadays mainly through needle sharing during intravenous drug use and due to poor hygiene standards in medical activities. In the past, many transmissions occurred through infected blood products before 1990, as well as lack of hygiene standards, e.g., when tattoos were pricked. Infection is further possible through anal intercourse and vertically from mother to child (approximately 5% risk of transmission) [4].

Hepatitis C virus is a single-stranded RNA virus and has three structural proteins (core, E1, E2) and seven non-structural proteins (p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A and NS5B) [5]. It has a large genetic variability, which manifests itself in six different genotypes with additional subtypes. Worldwide, genotype 1 infection is the most common (approximately 46%), with genotype 1 also responsible for nearly half of infections in Switzerland [6,7].

Course of disease, diagnosis, therapy

In HCV infection, an acute form is distinguished from a chronic form. Acute hepatitis C is often asymptomatic with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, abdominal pain, myalgias, and rarely icterus. It takes a chronic course in about 50-80% of cases.

A small multicenter German study demonstrated that six weeks of antiviral therapy with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir in a total of 20 patients with acute genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection resulted in a sustained virologic response in all cases, preventing chronicity of viral infection [8]. However, because acute hepatitis C virus infection is rarely recognized due to the unspecific symptoms and can often be asymptomatic, the therapy of acute hepatitis C plays only a minor role compared to the therapy of chronic hepatitis C.

Chronic HCV infection can be asymptomatic for a long time and only late in life can it cause non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, loss of performance, upper abdominal discomfort, itching or joint complaints. Extrahepatic manifestations such as cryoglobulinemia, HCV immune complex-mediated nephropathy, or non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma may also occur. Approximately 20-30% of patients with chronic HCV develop cirrhosis within the next 30 years. Risk factors for progression of fibrosis of liver tissue are primarily age >40 years at the time of infection, alcohol consumption of more than 50 g per day, and male gender [9].

The incidence for hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C-associated cirrhosis is approximately 3-6% [10].

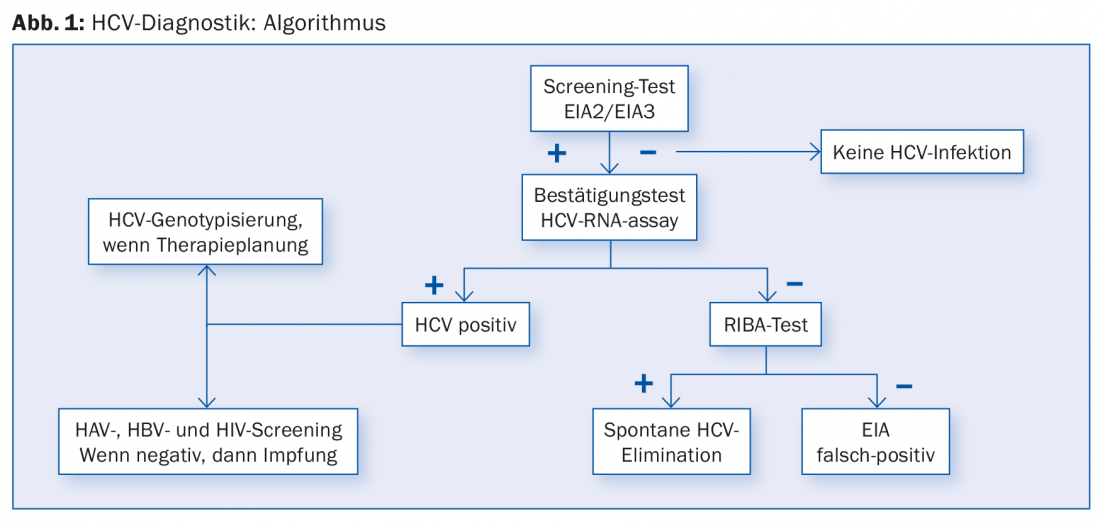

The Swiss Hepatitis C Cohort Study found that approximately 61% of patients with chronic HCV were born between the years 1955 and 1974 [11]. Especially in patients born in these cohorts with a corresponding risk history (i.v. drug abuse, blood transfusions before 1990, tattoos), one should also consider anti-HCV screening (Fig. 1) in case of persistent fatigue or other nonspecific complaints and seek treatment in case of positive findings. Otherwise, the usual risk groups such as persons with high transaminases, with HIV or HBV infection, with intravenous/intranasal drug use or piercing/tattooing, patients on dialysis, and children of HCV-infected mothers should be tested.

However, an anti-HCV screening test may be false-positive in some cases (Fig. 1). Therefore, HCV RNA PCR should always be performed if the screening test is positive. If HCV PCR is negative, it is either a passed HCV infection or a false-positive screening test. In this case, another immunoassay, the so-called RIBA assay (“recombinant immunoblot assay”) helps. This confirmatory test is more accurate than the anti-HCV screening test. If the RIBA assay is positive, it is a case of hepatitis C that has been passed through; if the result is negative, a false-positive anti-HCV screening test can be clearly assumed if the HCV PCR is negative at the same time; further investigations are then no longer necessary.

For a long time, therapy for hepatitis C consisted of a combination of pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin, which in the worst cases could last up to 18 months. Therapy responded in only 50-70% of patients with concomitant side effects, some of which were severe, such as hematotoxic effects, flu-like symptoms, fatigue, or psychiatric symptoms. The development of the new direct acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized HCV therapy. Instead of a long interferon therapy with moderate success rates and many side effects, the therapy with a DAA combination today proceeds with success rates of more than 95% and very good tolerability without significant side effects [12].

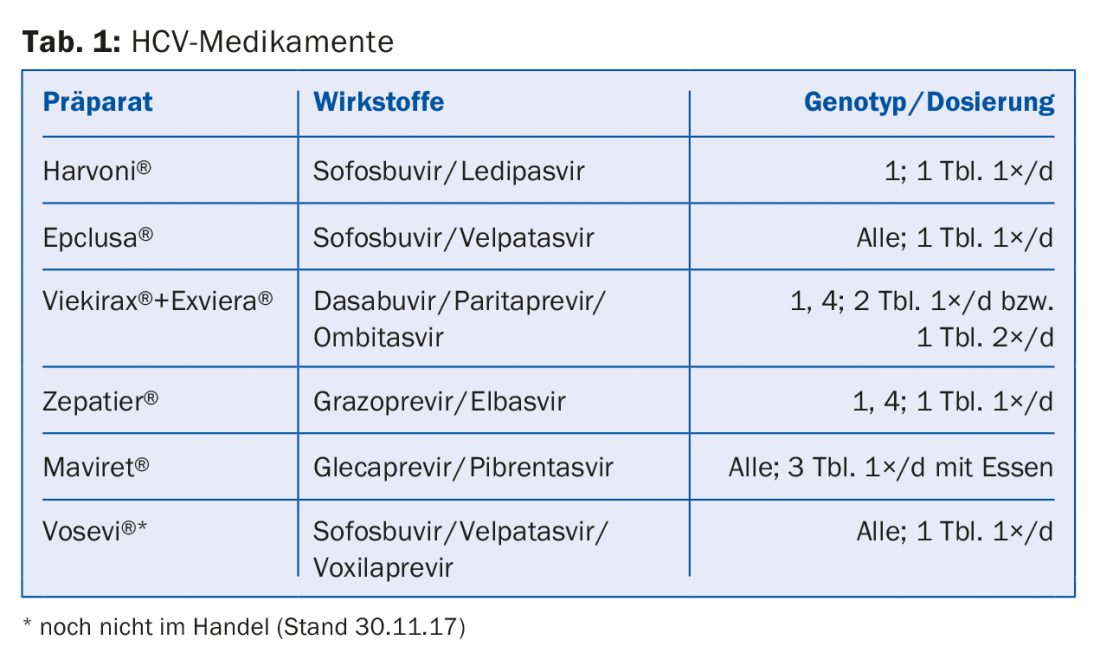

HCV NS5A inhibitors such as ledipasvir or velpatasvir inhibit the viral NS5A protein, which plays a role in HCV replication and modulation of cellular function, and end with the suffix -asvir. Among RNA-dependent NS5B polymerase inhibitors, nucleoside (NI) inhibitors such as sofosbuvir are distinguished from non-nucleoside inhibitors (NNI) such as dasabuvir – they end with the suffix -buvir. Protease inhibitors such as grazoprevir or glecaprevir inhibit the virus’s own NS3/A4 serine protease and end with the suffix -previr. Table 1 presents a selection of the drugs currently approved in Switzerland and subject to health insurance coverage.

Success indicators of the therapy

The success of antiviral therapy is evaluated twelve weeks after completion of therapy. If the viral RNA is no longer detectable by molecular biology using PCR, this is referred to as a sustained virological response (SVR), so that the patients can be considered virus-free and cured.

Meta-studies show that the probability of subsequent return of the virus within five years of cessation of therapy is less than 1% in the normal population and about 10% in the high-risk population (continuous i.v. drug use, prison inmates). However, in affected individuals, reinfection with the virus, often with a different genotype, is much more common than subsequent relapse [13].

Further studies show that achieving SVR reduces both liver-associated and extrahepatic mortality from hepatitis C virus infection [14]. Furthermore, achieving SVR is also associated with increased quality of life, which is why it is an established patient-relevant endpoint of hepatitis C therapy [14].

If SVR is achieved in patients without cirrhosis, laboratory monitoring of HCV RNA should be performed at approximately 12 months. If the test remains negative, patients are considered definitely cured and, in the absence of other hepatic risk factors, do not require follow-up. Patients with liver cirrhosis should continue to be seen every six months for clinical and laboratory monitoring and sonographic screening for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) even after SVR has been achieved.

HCC Recurrence

In two different cohort studies in Bologna [15] and Barcelona [16], it was found that patients with previous treated HCC inexplicably had HCC recurrence six months after completion of antiviral therapy in 29% and 27.6% of cases, respectively. Among patients without a history of HCC, HCC was detected in approximately 3.2% of cases in both studies. This association could not be confirmed in other studies. However, the number of studies on this is still small. Until more data are available on this topic, we recommend sonographic examination of the liver in practice before and after antiviral therapy.

Therapy planning

Until recently, therapy with DAAs was only available in Switzerland to patients with fibrosis grade 2 or higher of the liver due to the high prices. However, at the latest since Oct. 1, 2017, with the significant price reduction, the limitatio is no longer applicable; since then, DAA therapy has been mandatory for all HCV-infected patients, regardless of fibrosis stage.

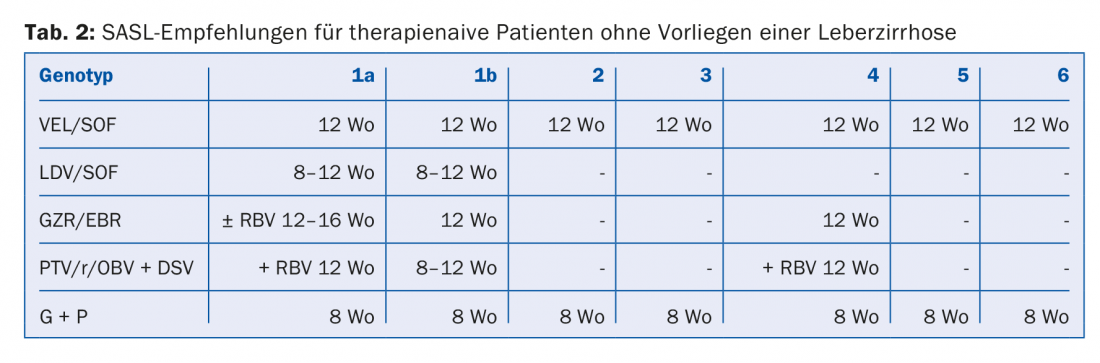

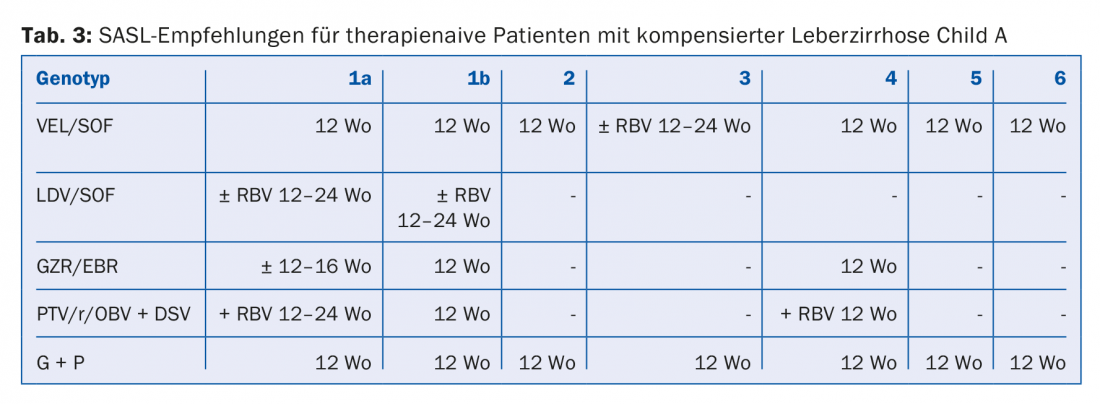

The following factors must be considered in the selection and duration of therapy: HCV genotype, cirrhosis/no cirrhosis, therapy-naive/therapy-experienced (and if so, which), and comorbidities.

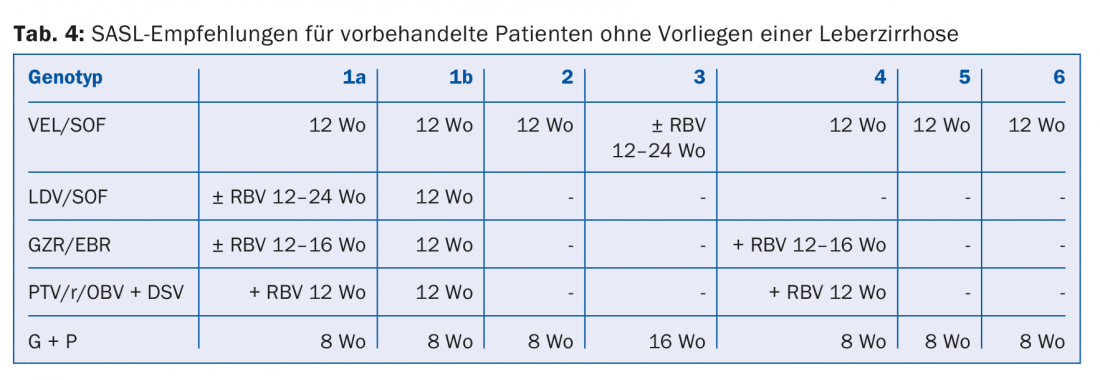

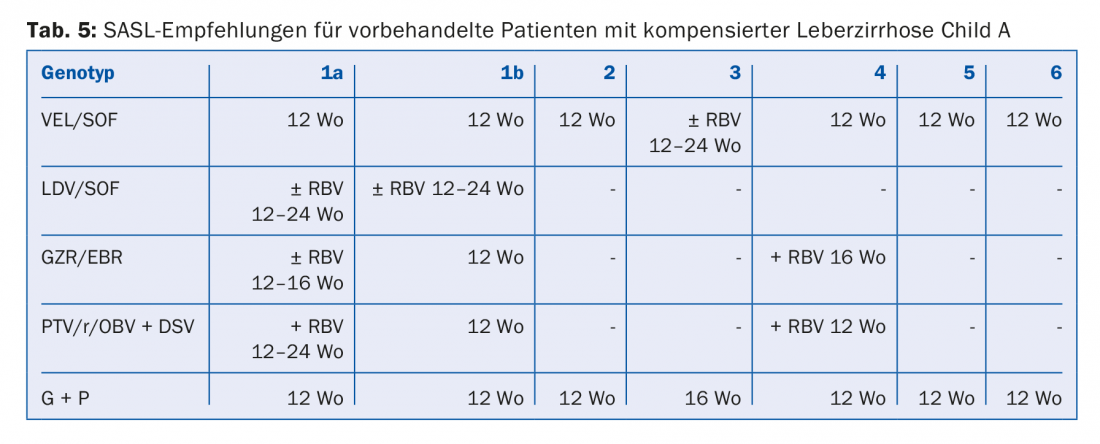

The DAA combinations recommended in the August 2017 SASL (Swiss Association for the Study of the Liver) guidelines can be found in modified form in Tables 2 to 5 for the respective constellations [17]. In addition, the treatment recommendations for the recently approved drug Maviret® (glecaprevir/pibrentasvir) are listed in each case in accordance with the technical information [18]. This has been allowed to be used and prescribed since Dec. 1, 2017.

Due to the constant updating of therapy recommendations, it is advisable to find out the individual therapy e.g. on the homepage www.sasl.ch or the smartphone app SASL HCV Advisor.

Of particular note are the DAA combinations sofosbuvir/velpatasvir and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, whose advantage is their pangenotypic high efficacy. In addition, the glecaprevir/pibrentasvir combination only requires a total therapy duration of eight weeks and was very well tolerated in the studies, with the most common side effects being headache (18-19%) and fatigue (9-12%) [19]. Consequently, this combination is considered particularly beneficial in patients with difficult compliance.

Therapy failure

Treatment failure of a DAA combination is usually due to a complex virological situation with the selection of resistance-associated variants (RAV), which is why re-therapy with a DAA combination + ribavirin should be initiated in a specialized center after resistance testing [20].

Alternatively, therapy with the new antiviral drugs glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir may be considered. For the combination sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir over 12 weeks, two large phase 3 trials (POLARIS 1 and 4) each achieved SVR rates of 96% and 98%, respectively, in all genotypes with prior treatment failure of a DAA combination [21]. The latter is expected to be approved in Switzerland in early 2018.

Interactions and contraindications

If other drugs are taken during antiviral therapy, it is essential to elicit their potential for interaction with DAAs (e.g., see www.hep-druginteractions.org or www.compendium.ch).

In particular, antiarrhythmic drugs, antibiotics, antidepressants, or anticonvulsants that inhibit the P-glycoprotein or interact with the CYP system often prove problematic. Thus, concomitant use of sofosbuvir and amiodarone can lead to life-threatening bradyarrhythmias [22].

In the presence of chronic renal insufficiency with an eGFR <30 ml/min, sofosbuvir-free combinations should be used [23]. Furthermore, therapy during pregnancy is contraindicated because a possible teratogenic effect of DAA could not be excluded by studies so far.

In patients with Child B/C cirrhosis and with previous decompensations, the use of protease inhibitors should be avoided because they reach a much higher concentration [23].

Only if primary care providers and specialists pull together will it be possible to achieve the common goal of the Swiss Hepatitis Strategy and the WHO, namely to eliminate HCV by 2030.

Take-Home Messages

- With the limit for most DAA combinations (“direct acting antivirals”) having fallen, therapy for chronic hepatitis C is available to all infected patients regardless of fibrosis stage and is covered by health insurance.

- The new DAA combinations make chronic hepatitis C curable in more than 95% of cases without the occurrence of significant side effects.

- If a SVR (“sustained virological response”) situation is achieved, the probability of a late relapse of hepatitis C infection is less than 1%.

- The pangenotypically active DAA combinations sofosbuvir/velpatasvir or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir are expected to further simplify the therapy of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the future.

Literature:

- WHO: Hepatitis C Factsheet. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/

- WHO: Global Hepatitis Report 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255016/1/9789241565455-eng.pdf?ua=1

- Zahnd C, et al.: Analyse de Situation des Hepatites B et C en Suisse. FOPH March 2017.

- Yeung CY, et al: Vertical transmission of hepatits C virus – current knowledge and perspectives. World J Hepatol 2014; 6: 643-651.

- Webster DP, et al: Hepatitis C. Lancet 2015; 385: 1124-1135.

- Messina JP, et al: Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology 2015; 61(1): 77-87.

- Bruggmann P: Hepatitis C epidemiology in Switzerland and the role of primary care. Praxis 2016; 105(15): 885-889.

- Deterding K, et al: Ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir fixed-dose combination for 6 weeks in patients with acute hepatitis C virus genotype 1 monoinfection (HepNet Acute HCV IV): an open-label, single-arm phase 2 study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: 215-222.

- Poynard T, et al: Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The OBSVIRC, METAVIR, CLINIVIR and DOSVIRC groups. Lancet 1997; 349: 825-832.

- Fattovich G, et al: Hepatocellulcar carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology 2004; 127: 35-50.

- Bruggmann P, et al: Birth year distribution in cases of hepatitis C in Switzerland. Eur J Public Health 2015 Feb; 25(1): 141-143.

- Zeuzem S: Treatment options in hepatitis C. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017 Jan; 114(1-2): 11-21.

- Simmons B, et al: Risk of late relapse or reinfection with hepatitis C virus after achieving a sustained virological response – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62: 683-694.

- Lee MH, et al: Chronic hepatitis C virus infection increases mortality from hepatic and extrahepatic diseases – a community-based long-term prospective study. J Infect Dis 2012; 206; 469-477.

- Conti F, et al: Early occurrence and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antivirals. J of Hepatol 2016; 65(4): 727-733.

- Reig M, et al: Unexpected high rate of early tumor recurrence in patients with HCV-related HCC undergoing interferon-free therapy. J of Hepatol 2016 Oct; 65(4): 719-726.

- SASL: Guidelines. https://sasl.unibas.ch/guidelines/SASL-SSI_HepC_EOS_Aug2017.pdf (last accessed 16 October 2017).

- Specialized information Maviret®. www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/004430/WC500233677.pdf (last accessed 16 October 2017).

- Zeuzem S: ENDURANCE-1: A Phase 3 Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of 8- versus 12-week Treatment with Glecaprevir/Pibrentasvir (formerly ABT-493/ABT-530) in HCV Genotype 1 Infected Patients with or without HIV-1 Co-infection and without Cirrhosis. The AASLD Liver Meeting, Boston 2016; Oral Presentation.

- Vermehren J, et al: Retreatment of patients who failed DAA-combination therapies – Real world experience from a large hepatitis C resistance database. J Hepatol 2016; 64; p188.

- Bourlière M, et al: Sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, voxilaprevir for previously treated HCV infection. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 2134-2146.

- Fontaine H, et al: Bradyarrhythmias associated with sofosbuvir treatment. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1886-1888.

- EASL: Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2016. J Hepatol 2017 Jan; 66(1): 153-194.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(1): 24-28