Imagine if 90% of all malignant tumors were not diagnosed or were detected as incidental findings but not specifically treated. Impossible? Fortunately, the situation is different for cancers, but not for alcohol use disorders.

According to estimates by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, approximately 250,000 people in Switzerland are dependent on alcohol, and almost a quarter of people over the age of 15 already exhibit high-risk alcohol consumption [1]. Not only the affected persons and their relatives are confronted with the consequences, which include more than 1600 deaths annually, but also society pays: the social costs of alcohol consumption amount to approximately 4.2 billion Swiss francs [2], 9% of all treatment costs in Swiss hospitals are caused by alcohol-related disorders.

In contrast to these immense follow-up costs, only a vanishingly small number of alcoholics receive specific treatment: About 500 people a year in inpatient addiction facilities and about 13,500 in outpatient counseling centers.

Primary care providers see an estimated three-quarters of them once a year, but often for other health conditions such as stomach problems, accidents or sleep disorders. A link to increased alcohol consumption is rarely addressed openly. Targeted brief intervention can succeed in getting patients to take the first step, inpatient detoxification. What are the treatment options in practice after detoxification has taken place?

Special challenges after withdrawal treatment has been completed

About half of the patients would like to be abstinent in the longer term after detoxification, while the other half aim for controlled alcohol consumption without clearly specifying what is meant by this. The latter is also quite a promising approach from a medical perspective, especially in milder forms of alcohol use disorder [3].

Unlike the still valid ICD-10, which only allowed a distinction between alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence, the DSM-5 [4] contains a reassessment of substance use disorders. These are no longer categorically separated, but described as one dimensional event, which allows a differentiation into mild, moderate and severe forms, which also allows therapy goals to be better adapted to the severity of the disorder.

Clinical assessment

Even during inpatient detoxification, a follow-up appointment should be scheduled with the primary care physician for the first week after discharge. In this, the patient should be praised for his or her performance and focused on positive changes. In the case of a severe form of alcohol use disorder, the dependence syndrome according to ICD-10, the primary goal should be to maintain abstinence. NICE guidance CG115 (2011) states that “Abstinence is the appropriate goal for most people with alcohol dependence, and people who misuse alcohol and have significant psychiatric or physical comorbidity (for example, depression or alcohol-related liver disease).” [5].

However, some patients will not want to follow a doctor’s clear recommendation for abstinence despite the presence of severe alcohol dependence. In these cases, or in the presence of harmful or risky use, it makes sense to aim for a reduction in use as a temporary therapeutic goal in terms of quantity, time and frequency, in the sense of harm reduction and harm minimization [6]. Supporting here are e.g. freely available apps [7,8]. Internet-savvy patients can take an online drinking test, set their personal drinking goals, and keep a detailed drinking diary. If desired, they can send regular status reports to their primary care physician.

Drug options

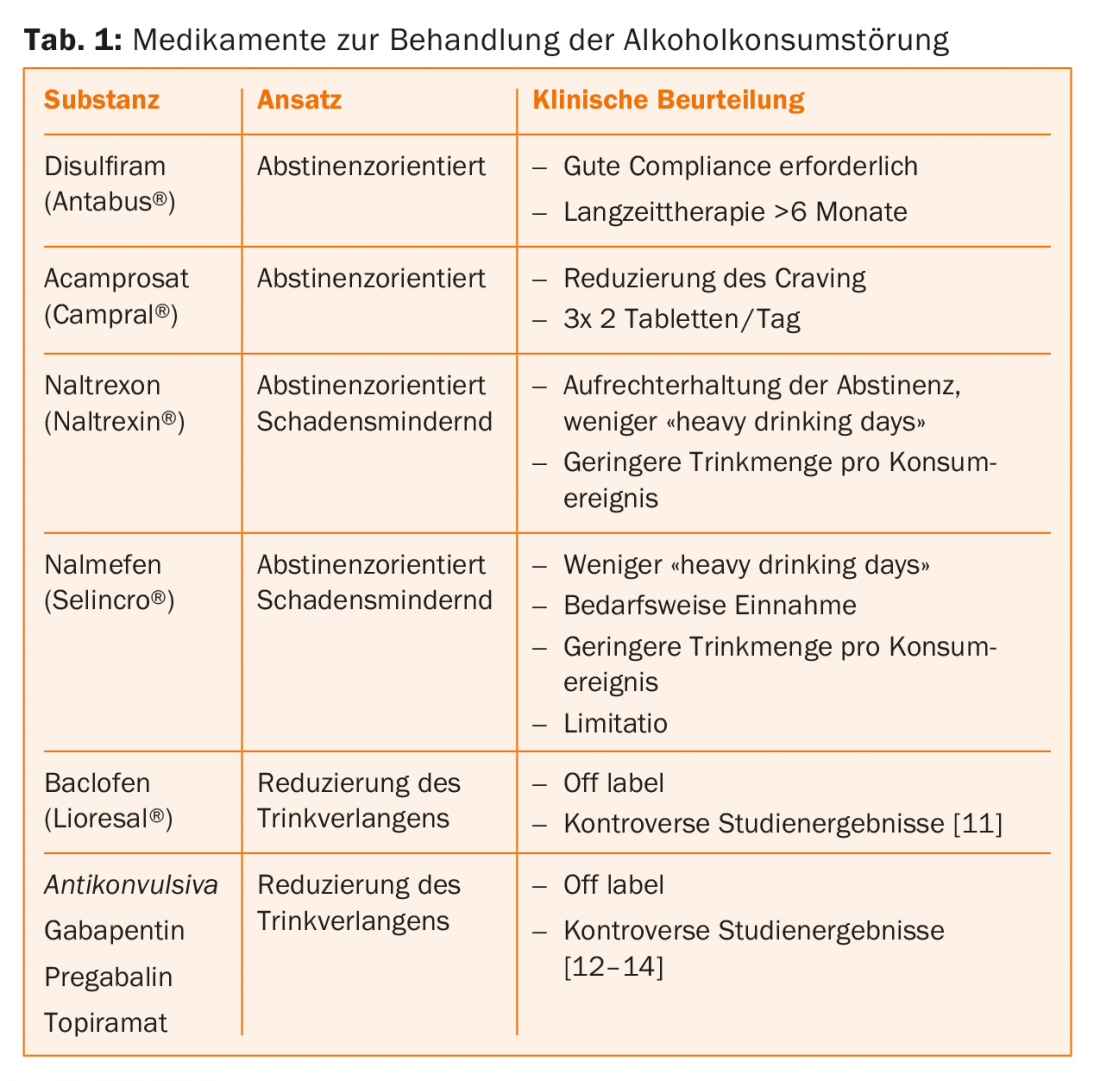

Abstinence-supportive or harm-reduction treatment approaches should include pharmacologic interventions. The general effectiveness of these approaches has been demonstrated in extensive studies with the highest level of evidence [9]. The drugs approved for the treatment of alcohol use disorders have different starting points (Tab. 1) . Disulfiram (Antabus®) would lead to a strong intolerance reaction when alcohol is taken again and works, among other things, through a deterrent effect. Acamprosate (Campral®) reduces alcohol cravings (“craving/tearing”) and thus can help ensure abstinence. The opiate antagonists naltrexone (Naltrexin®) and nalmefene (Selincro®) reduce the number of drinking days and the amount of alcohol consumed and are thus classified as harm-reducing approaches.

Disulfiram (Antabus®): The use of disulfiram (DS) requires detailed education, high compliance, and usually controlled and supervised intake. After taking disulfiram, even a small amount of alcohol leads to an extremely unpleasant and possibly dangerous reaction (disulfiram-alcohol reaction). The use is particularly suitable for those patients who have made a safe decision in favor of total abstinence. In addition to the pharmacological effect, the use of DS can lead to consolidating the abstinence decision once it has been made and make it easier for patients to struggle with it on a daily basis. The intake should be at least six months, better one year. Prior to discontinuation, a detailed assessment of abstinence should be made, possible risk factors discussed, and a course of action agreed upon for dealing with excessive alcohol intake. At the beginning of the therapy with DS, at least monthly contacts should take place, as well as the recommended laboratory tests should be performed (see technical info).

Acamprosate (Campral®): Treatment with acamprosate (ACP) should be started as soon as possible after withdrawal treatment has occurred. ACP can be considered as a modulator of the NMDA receptor complex, although the exact mechanism of action is not yet fully understood. The effect is reflected in a subjectively reduced desire to drink, which is perceived to increase with the duration of use. ACP is particularly suitable for patients who are striving for abstinence and subjectively suffer from “craving”. It has rather mild effects on relapse risk and abstinence duration [10]. ACP works best for patients who have total abstinence as a treatment goal and who want to stabilize already positive changes after a prolonged period of abstinence.

naltrexone (Naltrexin®) and nalmefene (Selincro®): The two opioid antagonists (OA) are suitable for medication support of withdrawal treatment for alcoholics after detoxification and should be embedded in a comprehensive psychosocial therapy program. They modulate dopaminergic, cortico-mesolimbic functions and thus directly reduce drinking pressure. The subjectively experienced reward and relaxation usually triggered by alcohol is reduced or absent, leading to a reduction or suspension of alcohol intake. Nalmefene is taken only on “risk days,” while naltrexin should be taken continuously, according to the Fachinformataion. Studies have shown a reduction in “heavy drinking days.” The side effects reported by many patients in the form of dizziness, nausea, insomnia, headache and confusion limit the range of use.

A trial of therapy with one of the opioid antagonists should be considered if a family history or strongly felt “craving/tearing” is present. OAs are particularly appropriate for patients with repeated crashes who have harm reduction drinking as a goal.

Dealing with relapses

In the case of repeated recidivism or failure to achieve the mutually agreed therapy goals, specific offers should definitely be included in the treatment, as this would usually go beyond the scope of regular practice operations.

Cooperation

Alcohol use disorder is a complex event. Genetic make-up, individual risk factors, psychosocial stress and, above all, psychiatric concomitant disorders require close cooperation with specialized institutions, especially in the case of chronic, more severe forms. Especially affective disorders, anxiety disorders, trauma sequelae and attention deficit syndromes occur frequently in addicted patients and require treatment by specialists. In this way, primary care providers can be relieved and patients can receive optimal therapy.

In the case of mild forms, it is often sufficient to have an appreciative conversation with a doctor, a brief intervention by a doctor or a referral to addiction counseling centers, which are usually organized on a decentralized basis. Specific interventions focus on teaching a disruption and recovery model. Patients are educated about the relationship between stress/tension and substance use, general problem-solving strategies are developed, and various tension reduction techniques are practiced. Specifically, these may include progressive muscle relaxation, mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques (“Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction”), imaginative techniques, endurance exercise, and more.

Outlook

Intensive collaboration between primary care providers and specialists may succeed in reducing the dramatic underuse of individuals with alcohol problems. Today, different treatment strategies are available, the effectiveness of which should be reviewed at appropriate intervals. The available drug strategies and options for brief intervention should be used more intensively in the future.

Take-Home Messages

- Primary care providers play a critical role in ensuring abstinence after detoxification.

- Through close cooperation with specialized institutions, even severe and complex courses can be successfully accompanied.

- The targeted use of available drug interventions can increase the success rate.

- In addition to abstinence-oriented approaches, harm-reduction approaches should definitely be offered.

- Appreciation of what has been achieved so far and appreciation of all efforts are the basis of all therapeutic efforts. In this way, it is possible to treat alcohol problems much earlier, more comprehensively and more successfully.

Literature:

- Addiction Monitoring Switzerland (2013-2015), FOPH.

- Fischer B, et al: Alcohol-related costs in Switzerland. Final report commissioned by the Federal Office of Public Health. Contract No. 12.00466. 2014; Polynomics, Olten.

- Körkel J: Controlled drinking. An overview. Addiction Therapy 2002; 3(2): 87-964.

- Falkai P, Wittchen H-U, (eds. German edition): Diagnostic criteria DSM-5 2015, Bern.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK): Alcohol Use Disorders: Diagnostic, Assessment and Management of Harmful Drinking and Alcohol Dependence. 2014; NICE Guideline 115.

- S3 Guideline Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Alcohol-Related Disorders, AWMF Register No. 076-001 (as of Feb. 28, 2016).

- www.redalc.ch (as of 10.2017)

- www.arud.ch/app.html (as of 10.2017)

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment: Incorporating Alcohol Pharmacotherapies Into Medical Practice: A Review of the Literature. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2009. SAMHSA/CSAT Treatment Improvement Protocols.

- Rösner S, et al: Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; (12): CD001867.

- Leggio L, Garbutt J C, Addolorato G: Effectiveness and safety of baclofen in the treatment of alcohol dependent patients. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2010; 9(1): 33-44.

- Furieri F A, Nakamura-Palacios E M: Gabapentin reduces alcohol consumption and craving: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68(11): 1691-1700.

- Martinotti G, et al: Efficacy and safety of pregabalin in alcohol dependence. Adv Ther 2008; 25(6): 608-618.

- Baltieri D A, et al: Comparing topiramate with naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Addiction 2008; 103(12): 2035-2044.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2017; 15(6): 9-12.