Fatigue often occurs during and after cancer therapy. Above all, exercise can help against this. Psychological measures also have positive effects. Pharmacotherapy, on the other hand, is of little use. So much for the results of a meta-analysis.

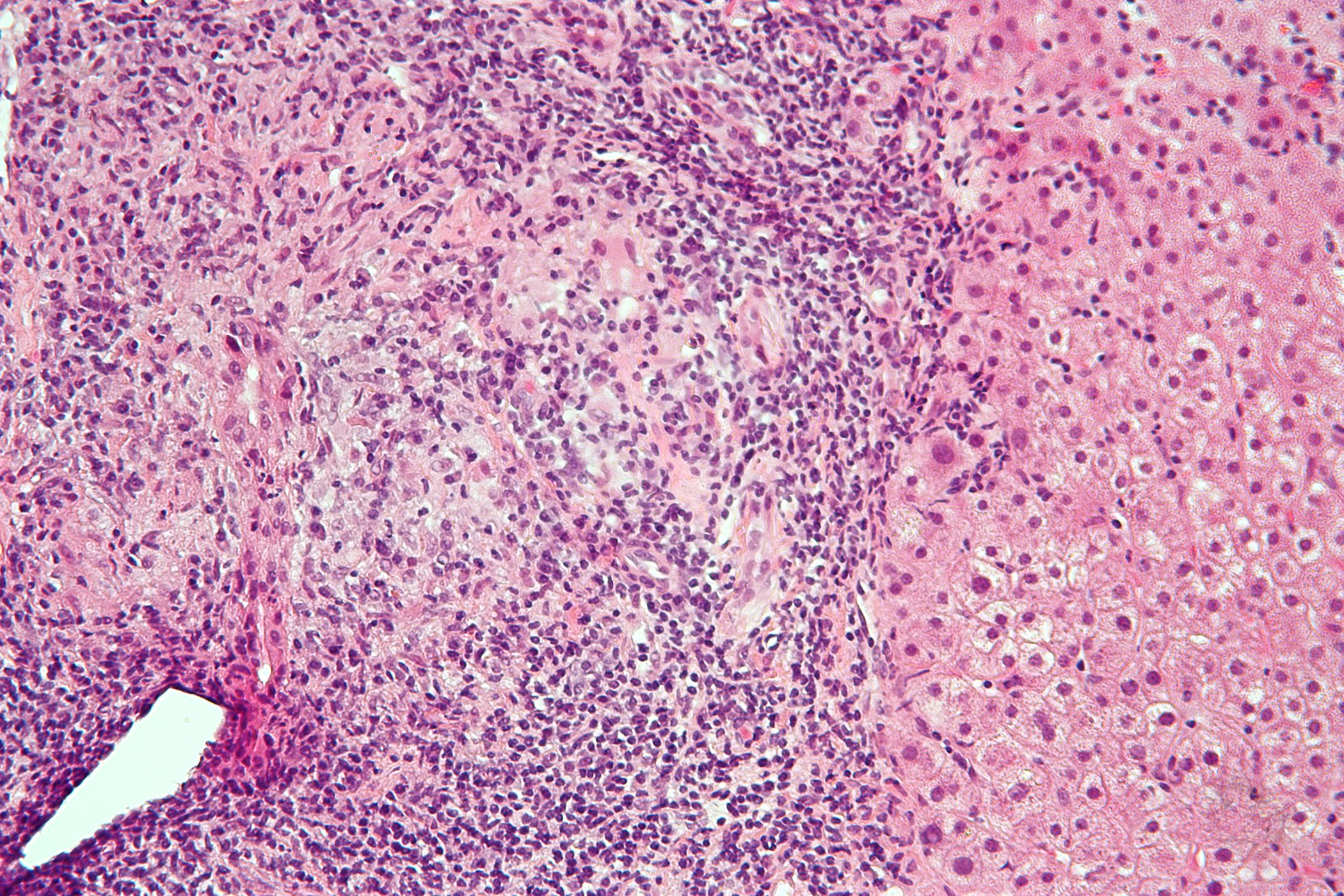

The meta-analysis from JAMA Oncology examined 113 individual studies with a total of 11,525 participants for the weighted effect sizes of four widely used interventions for tumor-associated fatigue: physical activity, psychological interventions, a combination of the two, or medication.

There is a need to catch up

Studying tumor-associated fatigue in more detail is important. The state of exhaustion, which can affect not only the physical, but also the affective and cognitive levels, remains one of the most common and stressful side effects of cancer (or its therapy). The consequences in the patient’s daily life in terms of quality of life and social reintegration are considerable. Cancer patients after radiation or chemotherapy are particularly affected. Fatigue can persist for a long time after the end of the (primary) therapy and isolate and burden the person in the long term.

The treatment of fatigue – and tumor-associated fatigue in particular – remains a challenge. In addition, it is still underestimated as an accompanying symptom in contrast to pain or nausea and too little attention is paid to it. The one is possibly related to the other: If the patient (apparently) has hardly any effective antidotes to offer, the diagnosis and thus naming of the problem is not as profitable as in the case of other secondary effects of a cancer disease or treatment.

Data evaluation

The study authors were interested in highlighting the most effective method against fatigue. For this purpose, they collected randomized clinical trials of adult cancer patients whose endpoints measured the severity of tumor-associated fatigue as a result of the above interventions. Data sources used were PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. Participants in the total of 113 studies examined, published between January 1999 and May 2016, were mainly women (78%), and the average age was 54 years.

12 Individuals in three independent groups evaluated the studies and calculated the respective effect sizes (including weighting). In addition, there was the standardized measurement of study quality.

The latter was good; no bias was evident. Both targeted exercise and psychological intervention (as well as the combination of the two approaches) were found to significantly improve fatigue during and after primary treatment. Sport and exercise had a slightly greater effect than the psychological measures. In combination with exercise, the latter were about as effective as alone. In contrast, the pharmacological intervention dropped significantly and hardly produced any benefit overall.

Recommend effective interventions

From the results, it can be concluded that physicians should primarily recommend exercise and/or psychological interventions to their patients with tumor-associated fatigue as first-line treatment. This finding is not new [1]. The heterogeneous effect of pharmacotherapy has also been repeatedly demonstrated [2] – although, of course, a distinction must be made between cause (e.g., anemia) and symptom treatment. The latter often targets only one particular aspect of fatigue and thus is unlikely to do justice to the multifactorial occurrence. In any case, the basis for a recommendation of non-drug measures is given. Psychosocial therapy can include psychoeducation, and relaxation therapy or meditation also have a positive effect. An individualized approach is indicated.

The behavioral measures are usually associated with a certain amount of effort (course attendance, etc.), which can only be conveyed to the patient if there is sufficient prospect of an improvement in exhaustion. Motivation thus plays a role that should not be underestimated. In addition, there should be general behavioral recommendations and strategies such as saving energy, setting priorities, delegating, scheduling activities at times of highest energy, activity diary, etc., which are always useful as an accompanying measure in fatigue.

Interesting concluding note: Although not demonstrated in this analysis, muscle building training appears to have an effect primarily on the physical fatigue component, and may have little effect on the emotional and cognitive components [3,4]. A combination of strength and endurance training is thus probably the most profitable.

Source: Mustian KM, et al: Comparison of Pharmaceutical, Psychological, and Exercise Treatments for Cancer-Related Fatigue – A Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol March 2, 2017. DOI:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6914 [Epub ahead of Print].

Literature:

- Strasser B, et al: Impact of resistance training in cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2013 Nov; 45(11): 2080-2090.

- Bruera E, et al: Methylphenidate and/or a nursing telephone intervention for fatigue in patients with advanced cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2013 Jul 1; 31(19): 2421-2427.

- Schmidt ME, et al: Effects of resistance exercise on fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Cancer 2015 Jul 15; 137(2): 471-480.

- Steindorf K, et al: Randomized, controlled trial of resistance training in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy: results on cancer-related fatigue and quality of life. Ann Oncol 2014 Nov; 25(11): 2237-2243.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(5): 6