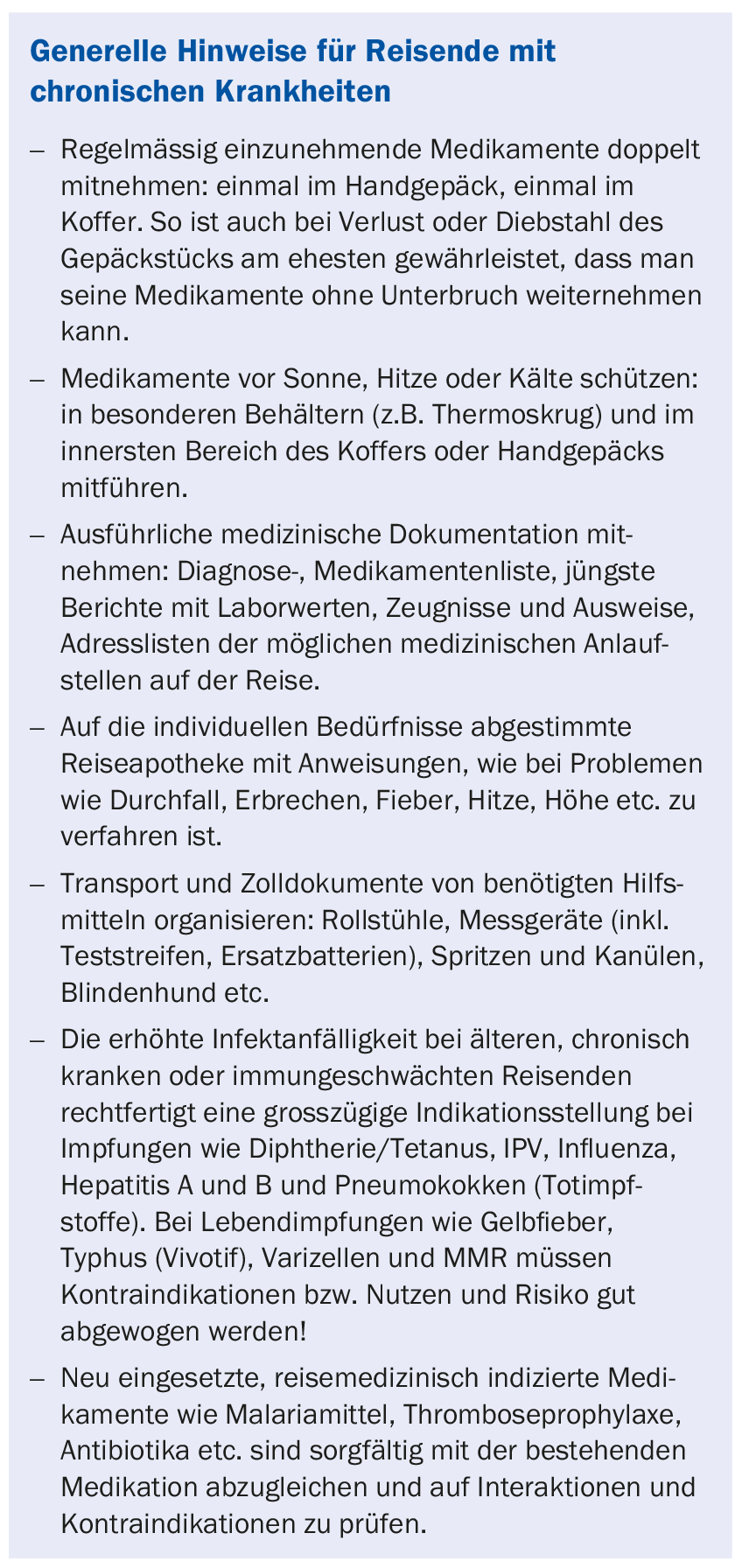

With careful preparation, well-adjusted and instructed patients with chronic diseases can take vacations in exotic countries. Taking into account interactions and contraindications for the individual disease and therapy, travel medicine measures such as vaccinations and malaria prophylaxis can be carried out in the majority of cases without any cutbacks. It is helpful to have good medical records, certificates and identification cards in two languages in case of on-site treatments. A properly equipped first-aid kit with therapy instructions should be supplemented for banal infections, exacerbations of the underlying disease, and emergency management. It is worthwhile to clarify the medical care at the destination.

When one takes a trip,

then he can tell something.

So I would take the stick and hat

and would choose to travel.

Matthias Claudius (1740-1815)

The urge to travel is immense, with over one billion international tourist arrivals recorded worldwide in 2014 (UNWTO Press Release, 27. Jan. 2015)! Such numbers can only be achieved if travel is suitable for the masses, i.e. easy, fast and inexpensive. Whether young or old, healthy or sick, there are almost no limits for modern travelers: everyone can get anywhere.

When Columbus presented his plans for an expedition to India, they frightened even adventurers and were rejected as impractical. Driven by greed for gold and power, Columbus set sail in 1492 with three small ships and a crew of soldiers of fortune and those condemned to death. A true suicide mission for the death-defying, who only had a chance of survival with luck and robust health. Today, an average tourist would hardly book such an eerie, punishing voyage with little chance of return. The travel medicine advice for this trip would accordingly also be very short: “Better stay at home, the risks are too great.”

Consultation before the trip

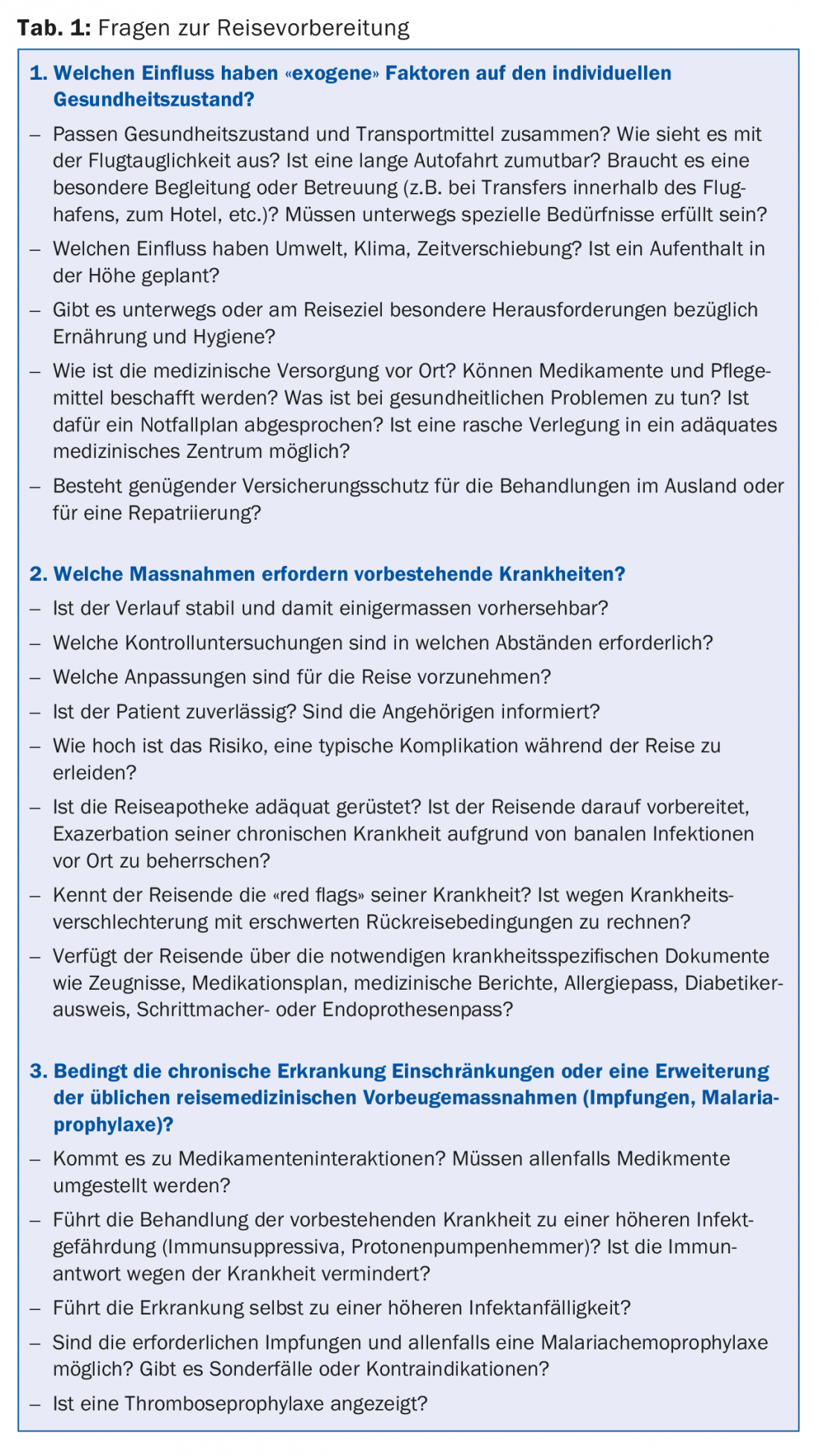

The most important principle of travel medicine consultation is to quantify and qualify the individual risk of the traveler and to recommend appropriate measures for this purpose. On the one hand, “exogenous” factors such as travel destination, travel duration and travel style are decisive, on the other hand, “endogenous” factors such as the individual state of health. Health factors can play a significant role in destination choice and have a limiting influence on travel activities. Therefore, travelers who are under regular medical check-ups and treatments in their daily life should get a careful travel medical consultation before the definite booking, but at least six weeks before departure. Essentially, all measures to keep the traveling patient healthy – disease-specific and travel medicine – must be coordinated. Close cooperation and exchange between the general practitioner and the travel medicine specialist is relevant for success. Among other things, various questions regarding preparation for the trip must be clarified (Tab. 1).

Preparation and ability to travel

Recreation and experiencing foreign countries and cultures are among the benefits of travel that people with chronic illnesses may also enjoy. Unfortunately, however, the effects of travel stresses such as climate change, altered daily patterns, trivial infectious diseases or travel stress are often underestimated. Many patients are more relaxed and at ease during the vacations, feel healthier and therefore forget their medication or take it only irregularly. After all, you’re on vacation, so why not take a “drug holiday”?

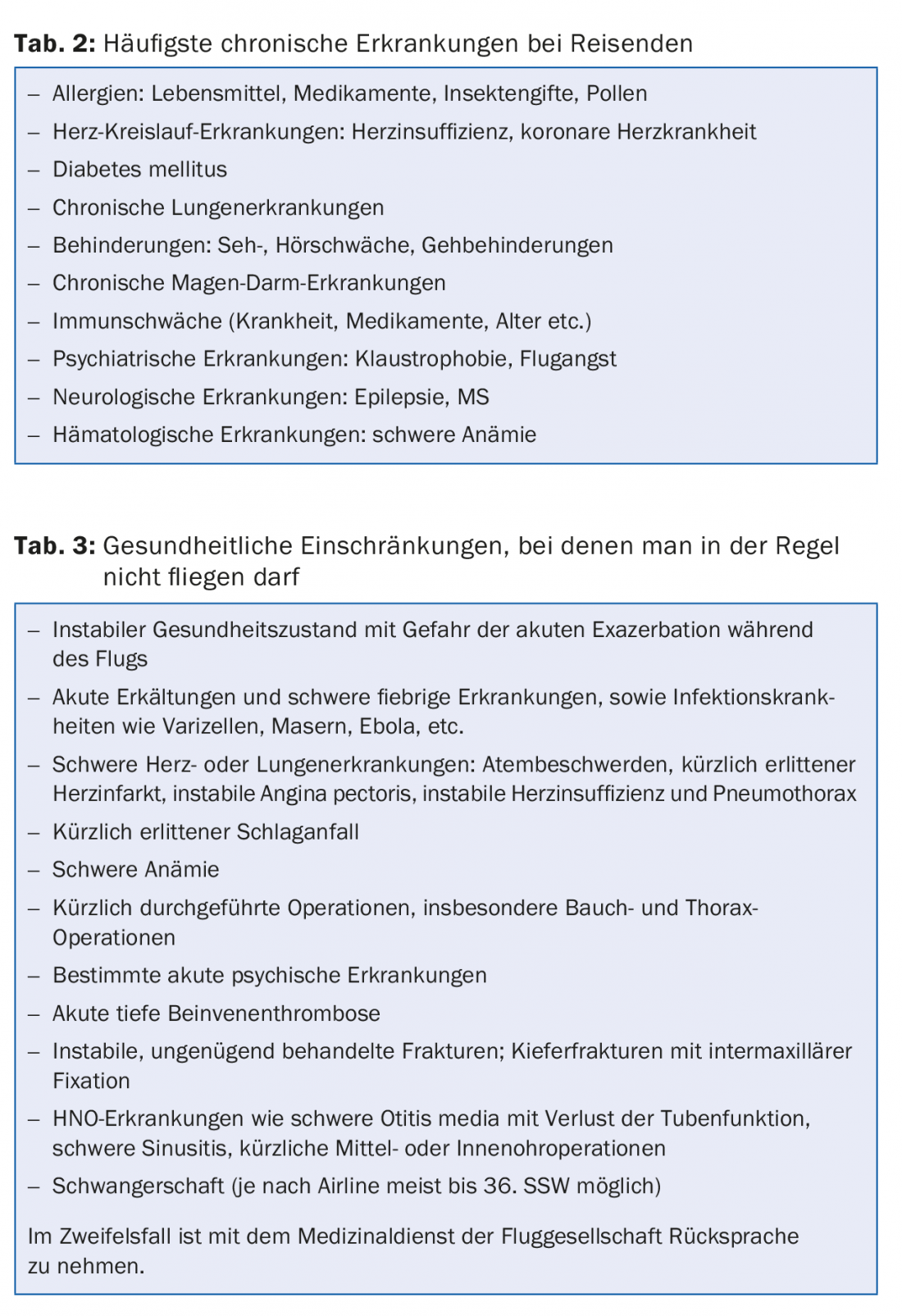

In order not to spoil the joy of travel, good preparation is essential. Stable control of the disease is an important prerequisite for enjoying a vacation (Tab. 2). The necessary measures adapted to the travel activity must be discussed in detail with the patient before the trip. Also, the most common complications and how to deal with them must be addressed, preferably with written instructions. A summary of the patient’s medical history in German and English, including a medication schedule, should be given to the patient for any contacts with health professionals at the destination. Many patients also appreciate being able to consult with their primary care physician by phone in an emergency.

More than with other means of transport, a trip by plane means additional stress for the body. Careful travel preparation for chronically ill patients includes a thorough medical examination to determine their fitness to travel or fly (tab. 3) . A simple rule of thumb is that someone who can walk up the stairs to the airplane (or a walking distance of 50 m) without shortness of breath is basically fit to fly. Detailed guidelines on airworthiness can be found in the “IATA Medial Manual” or on the websites of various airlines.

Allergies

Absolute contraindications for travel do not exist in case of allergies. As a rule, allergy sufferers have fewer complaints during vacations in foreign surroundings, at the seaside or in the mountains. Highly allergic patients should always carry an emergency kit with steroids, antihistamines and, if necessary, epinephrine (EpiPen®) as well as the current allergy passport. In the case of severe reactions to insect bites, it may be worth taking antihistamines as a preventive measure in addition to the consistent use of repellents. CAVE: sedating effect when driving a motor vehicle! Taking into account the specific allergies and the appropriate precautions, all vaccinations and malaria chemoprophylaxis are basically possible.

Cardiopulmonary diseases, severe anemia

Most medical emergencies during travel are cardiovascular related. Such emergencies during air travel may be favored by the reduced air pressure in the aircraft cabin (equivalent to 2000 – 2500 m.a.s.l.) or during exposure to high altitude, which is associated with a drop in oxygen saturation in the blood from 97 to 90% even in healthy individuals. Travel stress can also be problematic. Under these conditions, cardiac arrhythmias occur more frequently even in older, otherwise healthy people. Patients who have no additional oxygen requirements at rest also do not need oxygen on a flight (Tab.3).

Cardiopulmonary function should be evaluated prior to travel with history, physical examination, measurement of Hb (at least >9 g/dL), oxygen saturation, pulse, blood pressure, resting ECG, and pacemaker checks if necessary to assess the risk of travel activities and take appropriate action. Emergency medications such as nitroglycerin, bronchodilators, etc., and emergency instructions for fellow travelers should be included in carry-on luggage. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are additionally indicated in cardiopulmonary risk patients. Certain antimalarials (mefloquine) are not appropriate in all patients because of the potential for drug interactions or cardiac arrhythmias.

Thrombosis prophylaxis and anticoagulation

The risk of thrombosis due to prolonged confined sitting with venous congestion and dehydration (typically when flying) can be readily compensated for in most travelers with regular exercise of the legs, drinking water, and, if necessary, compression stockings. However, pre-existing coagulation disorders, obesity, smoking, and hormone therapy may create an alert situation for thrombosis with pulmonary embolism as a complication. In these cases (“seat time” on airplanes or buses over five hours combined with risk factors), drug thrombosis prophylaxis is indicated for air or bus travel. Increasingly, the new oral anticoagulants (NOAKs) are being used in addition to the proven low-molecular-weight heparins. There are no evidence-based data on this (off-label) use of NOAKs.

Patients who are anticoagulated with vitamin K antagonists may have certain advantages from switching to NOAKs: Laboratory monitoring is no longer required, drug or food interactions are less frequent (e.g., with the antimalarials atovaquone, proguanil, doxycycline).A prerequisite for safe travel remains in all cases a stable setting of oral anticoagulation.

Diabetes mellitus

When traveling and in foreign countries, diabetics have to be prepared for unusual situations. Time difference, the changed daily rhythm, unfamiliar activities and diet or even travel-related stress, diarrhea and banal infections can throw blood sugar out of balance. Antidiabetics may interact with antimalarials or other medications in the first-aid kit. Under these circumstances, blood glucose must be measured more frequently than usual. It must be taken into account that environmental conditions such as heat, humidity and exposure to high altitudes can affect the function of measuring devices (possibly additional checks with urine test strips). Medication regimens with instructions on how the patient should respond to blood glucose fluctuations are helpful. Antidiabetic drugs must be transported and stored correctly (in particular, insulins should not be stored at sub-zero temperatures or above 39°C), and they should be available in sufficient quantities (in duplicate) and in the usual form of administration (pen). The diabetic must always carry medication, meter, test strips, snacks, emergency kit (sugar substitute or glucagon injection) and the diabetic passport. Fellow travelers should be informed about emergency measures.

Immunodeficiencies

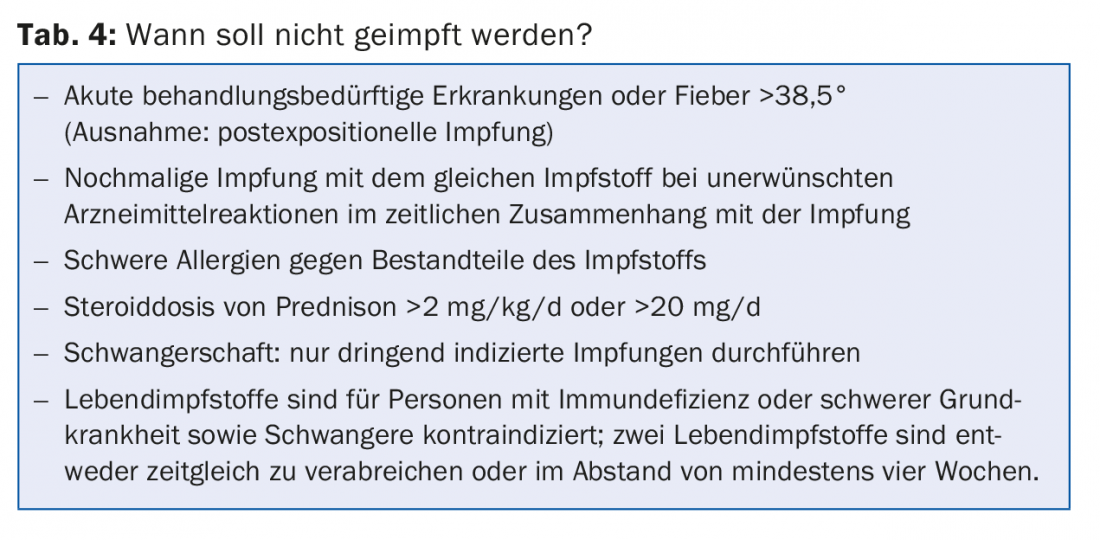

Special challenges arise for travelers with diminished immunocompetence. Affected individuals are those with HIV infection or AIDS, asplenia, chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, after organ transplantation or under immunosuppressive drugs (steroids, antiproliferative agents, anti-TNF drugs, cytostatics, etc.). Preparing for the trip is a distinctly team affair. The primary care physician, specialist, travel medicine physician and patient must harmonize well during preparation because of the complexity of the situation. Live vaccines (BCG, yellow fever, MMR, typhoid, varicella) are usually contraindicated in severely immunocompromised individuals. The attenuated immune response requires more frequent boosters or higher doses for the dead or inactivated vaccines. However, these vaccinations should not be omitted, especially in the case of immune deficiencies or pre-existing organ damage (e.g., chronic hepatitis), because an infection that can be avoided by vaccination is not reasonable as an additional burden (Tab. 4)! Indicated vaccinations are often omitted because certain circumstances are mistakenly regarded as contraindications.

Further reading:

- Steffen R, et al: Manual of Travel Medicine and Health,3rd Ed, ISBN 978-1-55009-369-8, 2007. DOI: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00364.x

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Information for International Travel 2014. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Field V, et al: Health Information for Overseas Travel. Journal of Travel Medicine 2011; 18: 149. doi:

- 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00497.x

- IATA Medical Manual, 7th Edition, March 2015.

- Ziegler T, et al: Airworthiness for vacation travelers.

- Brandenburg Medical Journal 3/2007 – Volume 17

- Stucki V: The patient on the move. Praxis 2010; 99(24): 1453-1464.

- www.britishairways.com/health/docs/before/airtravel_guide.pdf

- www.swiss.com/de/DE/vorbereiten/spezielle-betreuung/gesundheit-und-reisen

- Tropimed®, Copyright 2015 ASTRAL AG

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(5): 12-16