In recent years, the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) has changed dramatically: Various new agents have come onto the market that improve the prognosis of many MS patients and enhance their quality of life. Reason enough to inform primary care physicians about current MS therapy at this year’s KHM Congress. This was done by Stefanie Müller, senior neurologist at the Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen and head of the MS outpatient clinic there, with a practical, entertaining presentation.

MS is the most common neurological disease leading to permanent disability and early retirement in young and younger adults. The prevalence in German-speaking countries is 150/100 000; women are affected three times as often as men. In most patients, the disease manifests itself between the ages of 20 and 40, in about 12% only after the age of 50 (late onset MS). A distinction is made between three forms of progression:

- Relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS): This form affects 85% of patients. Individual episodes of the disease occur, from which not all sufferers recover. Between relapses, the condition does not deteriorate significantly. In approximately 50% of patients, untreated RRMS transitions to the

- Secondary progressive MS (SPMS): Gradual progression, steady increase in symptoms with or without additional relapses.

- Primary progressive MS (PPMS): In 10-15% of MS patients, the condition deteriorates continuously from the beginning, but phases of disease arrest may occur during the course. The age of onset is slightly higher (about 40 years), and equal numbers of men and women are affected.

MS is a diagnosis of exclusion

The most common symptoms at the onset of the disease are sensory disturbances (41.3%), visual disturbances (36.9%), gait disturbances (31.8%), and paralysis (23.4%). However, other complaints may also occur, for example, dizziness, bladder disorders or disorders of fine motor skills. “MS is a diagnosis of exclusion,” the speaker emphasized. “When neurological symptoms are present, other diagnoses must first be ruled out. Theoretically, it would be possible to diagnose MS without MRI imaging, but in practice no one does that anymore.”

The typical findings on MRI (periventricular, callosal, infratentorial, and spinal lesions, some with contrast uptake, some “black holes”) not only underscore the diagnosis but are also important for follow-up and assessment of prognosis. Not every lesion that is visible on MRI causes a relapse: it is assumed that only every tenth lesion also causes a relapse. The number of black holes, i.e. axonal substance loss, is a correlate for disability.

Brain atrophy leads to cognitive deficits

The natural course of MS depends on the form of the disease. In RRMS, 11-15 years after onset, 50% of patients suffer from SPMS, 50% require a walking stick; 30 years after onset, 83% require a walking stick, 34% are bedridden. In PPMS, the course is less favorable: already five years after onset, half of the patients require a walking stick, and 22 years after onset, 50% are bedridden.

“However, MS not only causes disability, but also results in brain atrophy,” Stefanie Müller said. “In healthy individuals, 0.1-0.4 percent of brain volume atrophies per year, compared to 0.5-1 percent in MS patients.” Accordingly, 40-60% of patients suffer from cognitive deficits, which can occur early in the course of the disease and hardly correlate with the extent of physical disability. Typical examples are a decrease in the ability to “multitask” or a reduced speed of information processing. These cognitive impairments cannot be diagnosed with the Mini-Mental Status Test; more targeted neuropsychological examinations are necessary here.

A very important but often neglected symptom is fatigue, from which 75-90% of patients suffer severely. “For more than half of MS patients, fatigue is the worst of all MS symptoms,” the speaker opined. The psychosocial consequences of MS are also eminent: 33-45% of patients take early retirement, every second patient develops depression (mostly organically caused), and the divorce rate is increased by 40% in MS patients.

Steroids in acute relapse: oral administration also possible

An acute MS episode occurs when

- There is a reported or clinically objectifiable symptomatology consistent with a demyelinating event in the CNS (symptoms do not need to be objectified),

- the symptomatology persists for at least 24 hours,

- the symptoms cannot be explained by an infection or a change in body temperature (Uhthoff phenomenon, see box).

Therapy consists of administering high-dose steroids as early as possible. Until recently, these were considered to be administered intravenously over 3-5 days. However, according to a recent study, oral treatment (1 g/d methylpredinsolone for 3 days) works equally well as intravenous [1]. “In Switzerland, methylpredinsolone is unfortunately only available in tablets of 100 mg,” Stefanie Müller regretted. “So with oral therapy, patients have to swallow ten tablets a day.”

In severely disabling relapses, e.g., with loss of visual acuity or paraplegia, there is the option of ultrahigh-dose steroid therapy (2 g/d) and/or plasmapheresis. An MS relapse is always a sign of disease activity, so a neurologic evaluation should be performed. Here, it is a matter of establishing long-term therapy in the first place or, at best, changing it.

Long-term therapy for MS

“Time is brain” also applies to MS. The earlier the disease is diagnosed and the earlier basic therapy is started, the better the long-term prognosis of patients. Today, there are a number of MS therapeutics available, three of which can be taken orally: Fingolimod, teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate. Some important aspects must be taken into account during therapy with these substances.

Fingolimod (Gylenia®) reduces peripheral lymphocyte counts by approximately 70%. However, the depth of the lymphocyte count does not correlate with the frequency of infections. Differential blood work must be done every three months during the first year of treatment, and every six months thereafter. If the total leukocyte count falls below 0.1× 109/l, treatment must be stopped. Macular edema occurs in 0.3% of treated patients, mostly within the first 3-4 months. Interaction with Cyp 3A4 inhibitors may increase fingolimod concentrations (e.g., during therapy with protease inhibitors, antifungals, or clarithromycin).

Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera®) reduces lymphocyte counts by approximately 30%, mostly within the first year of therapy. A differential blood count must be obtained every three months for the first 1.5 years and every 6-12 months thereafter. A break in therapy is appropriate if leukopenia below 3.0× 109/l or lymphopenia below 0.5× 109/l occurs. Liver and kidney function must also be checked regularly.

Teriflunomide (Aubagio®) is subject to enterohepatic circulation, therefore it has a long half-life. The effect may be enhanced or attenuated by numerous interactions (St. John’s wort, furosemide, ciprofloxacin, etc.), and teriflunomide itself may enhance (repaglinide, pioglitazone, steroids, etc.) or attenuate (duloxetine, tizanidine, etc.) the effect of other drugs.

Vaccinations, vitamin D and pregnancy

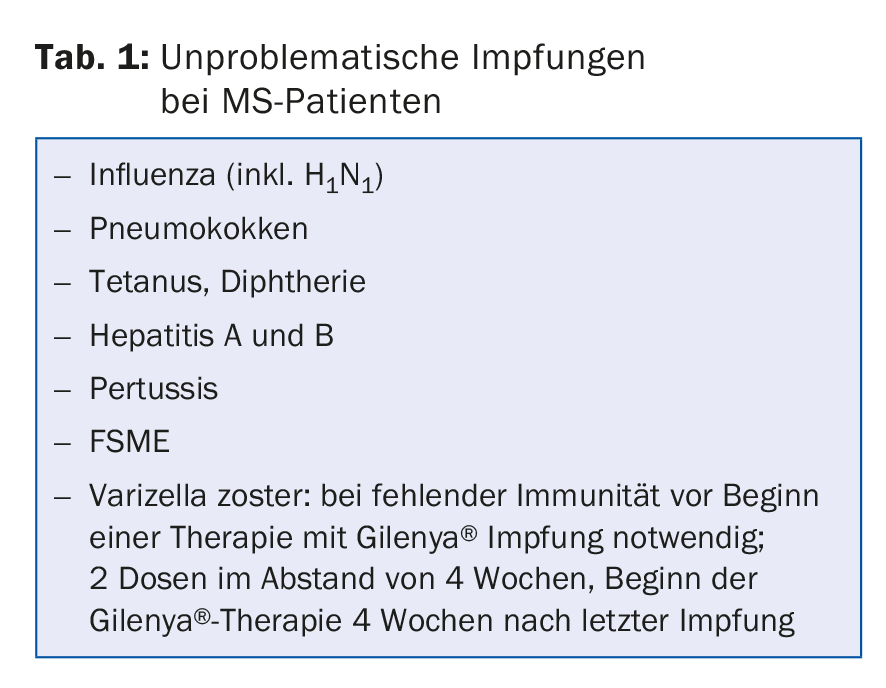

Infections can trigger MS relapses in some patients, and at the same time, some MS therapeutics increase the risk of infection. Therefore, it is reasonable to protect MS patients against infections with vaccinations (Tab. 1). However, patients should not be vaccinated during an attack and not earlier than 2-4 weeks after the last steroid dose.

The relationship between vitamin D deficiency and MS is controversial. In spring, when vitamin D levels are low, MS relapses are more common. And there is a clear north-south divide in MS incidence: more people have MS in Sweden than in Switzerland, and more in Switzerland than in Italy. Nevertheless, there are (still) no recommendations for the vitamin D supply of MS patients in this country, unlike e.g. in Brazil.

During pregnancy, the immune system is inhibited, which means that pregnant MS patients have fewer relapses. This association between MS and pregnancy could perhaps and at least partially explain why the incidence of MS in women is increasing: Women in industrialized nations are becoming pregnant less often and later in life, so they benefit less from the “MS-inhibiting” mechanisms of pregnancy.

Source: KHM Congress, Lucerne, June 23-24, 2016

Literature:

- Le Page E, et al: Oral versus intravenous high-dose methylprednisolone for treatment of relapses in patients with multiple sclerosis (COPOUSEP): a randomised, controlled, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2015; 386(9997): 974-981.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(9): 35-37