Oncological rehabilitation is a specialized form of rehabilitation that is becoming established in the Swiss health care system. It offers patients with tumor diseases the chance to better overcome cancer and the consequences of therapy in their bio-psycho-social dimension and helps them to regain physical function, autonomy and the best possible participation/participation in all areas of life. The goal of the activities currently underway is to implement it as an integral part of the oncology treatment continuum. Appropriate assessments and resulting therapies should be part of every oncology treatment from the beginning, so that the proportion of patients with rehabilitation-relevant problems can be identified early on and treated in an interdisciplinary program.

There is hardly any other field in which such striking progress is currently being made as in oncology. Currently, about 37,000 mainly elderly people are diagnosed with cancer in Switzerland every year, and 16,000 people die from this disease. However, thanks to increasingly better treatment methods, those affected can expect a significantly higher life expectancy: The 5-year survival rate for all cancer diagnoses has increased from 49% (1975-1977) to 67% (2001-2007) [1], and the trend is still rising. Many cancers thus become a “chronic disease.” The number of patients diagnosed with cancer in Switzerland (“cancer survivors”) has more than doubled from 140,000 in 1990 to almost 300,000 in 2010 [2]. This means that people with a cancer diagnosis continue to live for years and that the improvement of the quality of life as well as the best possible reintegration into the usual life, incl. the treatment of cancer, is of great importance. reintegration into working life is playing an increasingly important role.

Definition

Oncological rehabilitation is a health- and autonomy-oriented process that includes all coordinated measures of a medical, educational, social, and spiritual nature that enable the cancer patient to overcome disabilities or limitations caused by the disease or by the therapy and to regain optimal physical, psychological, and social functionality – in such a way that he or she can shape his or her life under his or her own power with the greatest possible autonomy and resume his or her place in society [3].

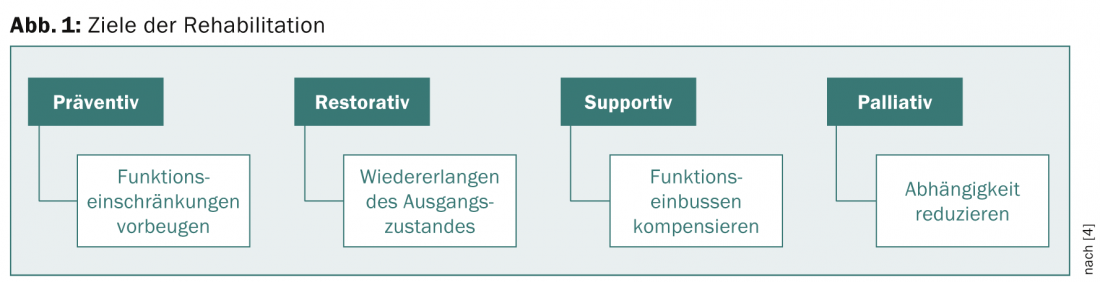

Rehabilitation goals

Rehabilitation measures are always goal-oriented. According to Cheville [4], a distinction is made between preventive (preventing functional impairment), restorative (regaining a baseline condition), supportive (compensating for functional impairment), or palliative (reducing dependence) goals (Fig. 1).

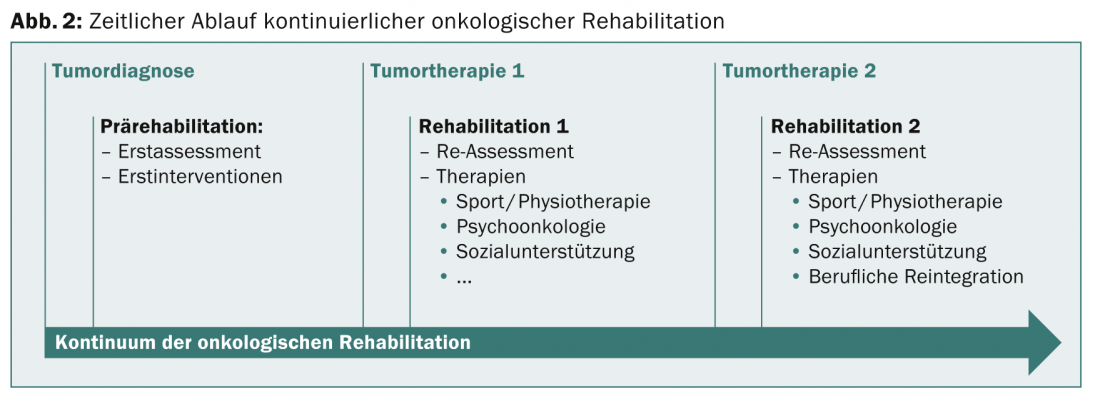

Rehabilitation can occur at any stage of tumor disease. The term “pre-rehabilitation” is used to describe a type of care in which initial assessments are carried out immediately after diagnosis and rehabilitation measures are initiated in order to create optimal physical and psychological conditions for the therapies that are about to begin. Individual studies have shown that patients who undergo an exercise program in the phase leading up to the start of actual oncologic therapies have fewer postoperative complications, lower postoperative morbidity, and shorter hospitalizations, along with improved quality of life [1].

Examples of goals for pre-rehabilitation include:

- Improvement of cardiovascular, pulmonary, and musculoskeletal functions.

- Improvement of proprioception to reduce the risk of a fall

- Reduction of anxiety through psycho-oncological counseling

- Support of preoperative smoking cessation before pulmonary interventions

- Nutritional counseling

- Pelvic floor training before urological surgery

- Swallowing training before ENT procedures.

The bio-psycho-social approach

Tumor diseases represent a rehabilitative treatment continuum from the time of diagnosis to, in some cases, years after completion of acute therapy (Fig. 2) .

Interdisciplinarity is an essential quality feature and superior to monodisciplinary therapies. Ongoing national cancer programs promote the development of “integrated care through patient pathways (with nursing, rehabilitative, psychosocial, psycho-oncological, and oncology-palliative approaches), optimization of interfaces between and within preventive care and different treatment pathways, between inpatient, outpatient, and home care, and between medical and non-medical services” [2].

The consequences of tumor diseases are manifold and depend on tumor type, stage and prognosis as well as on the therapies performed. Common problems include nausea and inappetence, dysphagia (in ENT or gastrointestinal tumors), weight loss, pain, complex wound and stoma problems, lymphedema, neurological problems (polyneuropathy) after chemotherapy, physical deconditioning and tumor fatigue, radiation field wounds, as well as psychological problems related to tumor diagnosis. Approximately one quarter of cancer survivors complain of long-term physical limitations [1], extrapolated to approximately 75 000 people in Switzerland.

Movement and training

One focus for restoring disease-specific and individual physical and psychological components is exercise therapy [5]. In addition to physical progress, regaining mobility and independence as a consequence of training also has a positive impact psychologically and mentally and affects various dimensions of quality of life. Especially in view of the tumor fatigue, which often takes years to develop, early and targeted physical training is highly recommended. The patient should be able to improve body confidence and self-efficacy, increase performance, and gain a sound knowledge of interrelationships as part of active therapy [6]. Complementary passive measures and targeted relaxation methods are also an integral part of the therapy, supporting psychophysical regeneration and helping to bring the body back into balance.

Additional physical and occupational therapy treatments are based on the individual and disease-specific limitations and resources of the patients with a view to optimal reintegration into their personal environment. The spectrum includes, among other things, extensive self-management, breathing exercises and heat treatments, scar treatment, swallowing training, brain performance training, gait training and dealing with aids in everyday life.

Psycho-oncological counseling

A cancer diagnosis is usually perceived as a profound, existentially threatening life experience that places an extraordinary burden on patients and also their families and environment. Consequences are pain, anxiety, depression, insecurity, changes in life planning and role expectations, in the social environment and leisure time, danger of social withdrawal, sexual problems, tumor fatigue, etc. The presence of a mental disorder favors this. Even among cancer survivors, 10% still complain of long-term psychological problems (“poor mental health”).

Psycho-oncological measures target psychological and social problems as well as dysfunctions in the context of cancer and its treatment. They aim to support disease management, improve psychological well-being as well as concomitant and consequential problems of medical diagnosis or therapy, strengthen social resources, enable participation and thus increase the quality of life of patients and their relatives [7]. The Swiss Society for Psycho-Oncology (SGPO) awards the titles “Psychooncological Counselor” or “Psychooncological Psychotherapist” for this activity.

Psycho-oncological counseling means the support and accompaniment of patients affected by cancer and their relatives in all phases of the disease and its psychological, social and health consequences. They accompany them in coping with their new living situation, social reintegration and reintegration into the work process.

In contrast or in addition, psychooncological psychotherapists provide psychotherapeutic treatment for patients and relatives with psychiatric comorbidities. Every institution that provides cancer treatment should integrate basic psycho-oncology screening into the standard procedure of every treatment early on and repeat the screening during the course of treatment.

Situation Switzerland

Oncological rehabilitation as an independent form of rehabilitation is still a young specialty in Switzerland. However, in recent years there have been many activities in both outpatient and inpatient settings with the aim of establishing oncological rehabilitation as a fixed component of cancer treatment.

Inpatients are predominantly admitted immediately after severe courses of major surgical procedures or after radiation and/or chemotherapy. There is a discernible trend toward patients being referred earlier and with increasingly “acute” problems (ongoing centalvenous antibiotic or nutritional therapies, complex wound and stoma problems, severe deconditioning and immobility) that need to be managed by appropriately specialized staff.

The development of oncological rehabilitation under the responsibility of the Oncoreha Association (www.oncoreha.ch) is a subproject of the National Cancer Programs (NCP). Priorities of the National Cancer Program from 2005-2010 were regional funding initiatives and network building. The main areas of action of the projects from NCP II for the years 2010-2015 are the expansion of expertise, the development of quality standards, and the securing of funding for oncological rehabilitation [8].

These initiatives have now given rise to numerous outpatient rehabilitation services throughout Switzerland, and a working group of the Oncoreha Association is also currently drafting quality standards for oncological rehabilitation.

Evidence base

Various studies and reviews have demonstrated the evidence of impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation for different tumor types, showing improvements in quality of life, fatigue symptoms, depression, walking distance in the 6-minute walk test, and various muscle strength parameters for all stages of the disease [9].

Cochrane reviews in recent years confirm that, albeit with certain limitations due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, significant improvements in tumor fatigue [10], physical performance, anxiety and depression, sleep disturbances, social function, and quality of life can be achieved by aerobic exercise therapy even during active tumor treatment [11]. For cancer survivors of various tumor types, significant positive effects of sports and exercise therapy on quality of life, breast cancer concerns, body image and self-esteem, emotional well-being, sleep disturbances, anxiety, depression, and pain have also been demonstrated [11]. In a review of 30 articles, the authors conclude that psychosocial care-based interventions and information (in the sense of psycho-oncology counseling) combined with supportive care can achieve improvements in mood for patients with a new cancer diagnosis [12].

Finally, there is evidence from various studies that rehabilitative interventions can reduce direct and indirect costs and are therefore cost-effective [1].

Perspectives

As a result of the ongoing support measures of the national cancer programs, interdisciplinary outpatient programs have now increasingly been established in addition to inpatient programs (Bern, Thun, Zurich, etc.), although their funding remains unclear. Quality criteria for program accreditation are under development as a subproject of the National Cancer Programs led by the Oncoreha Association. Evidence of efficacy of such interdisciplinary programs has been demonstrated in numerous studies, although further studies are needed to define the optimal intensity and mix of therapy.

With regard to the calculated treatment needs for Switzerland, it appears to make primary sense to use already existing rehabilitative structures. However, rehabilitation programs must be more responsive to the problems associated with oncologic disease, which primarily involves adapted medical care, nursing, and therapy [3]. Likewise, resources in the area of psycho-oncology must be demanded accordingly. It is desirable to establish treatment chains that treat patients as inpatients as well as outpatients. Programs must be evaluated regularly for sustainability.

Josef Perseus, MD

Literature:

- Silver JK, et al: Impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation: an essential component of quality care and survivorship. CA Cancer J Clin 2013 Sep; 63(5): 295-317.

- Oncosuisse: National Strategy against Cancer (NCS) 2014-2017; www.oncosuisse.ch.

- Eberhard S, Buser K: Rehabilitation in oncological diseases. Swiss Journal of Oncology 2007; 3: 45-51.

- Cheville A: Cancer rehabilitation. Seminars in Oncology April 2005; 32: 219-224.

- Baumann FT, Schüle K: Exercise therapy and sport in cancer – guide for practice. Deutscher Ärzteverlag Cologne 2006.

- Catuogno S: Sports and fatigue in cancer – sports therapy as a component of inpatient oncological rehabilitation. Family Practice 2012; 6-7, 39-41.

- AWMF S3: Guideline Psychooncological diagnosis, counseling and treatment of adult cancer patients 1-2014.

- Oncosuisse: National Cancer Program for Switzerland 2011-2015 (NCP II) www.oncosuisse.ch.

- Fong DYT, et al: Physical activity for cancer survivors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2012; 344: e70.

- Cramp F, et al: The effect of exercise on fatigue associated with cancer. Cochrane Review Published Online: 14 November 2012.

- Mishra SI, et al: Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for people with cancer during active treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Aug 15; 8.

- Galway K, et al: Psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life and emotional wellbeing for recently diagnosed cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Nov 14; 11.

- Swiss Society of Psychooncology; www.psychoonkologie.ch.

- Scott DA, et al: Multidimensional rehabilitation programmes for adult cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 6.

- Khan F, et al: Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for follow-up of women treated for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 12.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2014; 2(8): 23-26.