Treatment of arterial hypertension in elderly and frail patients presents challenges at many levels. Because they tend to be at increased risk for adverse effects, medication should be started cautiously. Target values are 130-139 mmHg systolic and 70-79 mmHg diastolic.

Treatment of arterial hypertension in elderly and frail patients presents challenges at many levels. Nevertheless, we will encounter this scenario with increasing frequency, as the growing proportion of elderly and very elderly patients with arterial hypertension is expected to lead to an increase in frail patients and patients with cognitive and functional limitations.

The European Hypertension Guidelines define elderly patients as those ≥65 years and very old as those ≥80 years [1]. Nevertheless, the temptation to consider only chronological age in the management of arterial hypertension should be resisted; rather, biological age is crucial. Age alone should never be a reason for withholding necessary antihypertensive therapy [1].

Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of arterial hypertension is constantly increasing as the population ages and the incidence of hypertension shows a clear age dependency. Life expectancy for an 80-year-old person is currently estimated to be about 9 years, three years longer than it was in 1970 [2]; the percentage of people over 80 in the European Union is put at 5.4%.

The prevalence of arterial hypertension is approximately 60% in >60-year-olds and 75% in >75-year-olds [1]. Data from Italy and France show that >80% of nursing home residents have arterial hypertension and that >80% are taking antihypertensive therapy.

Pathophysiological peculiarities in old age

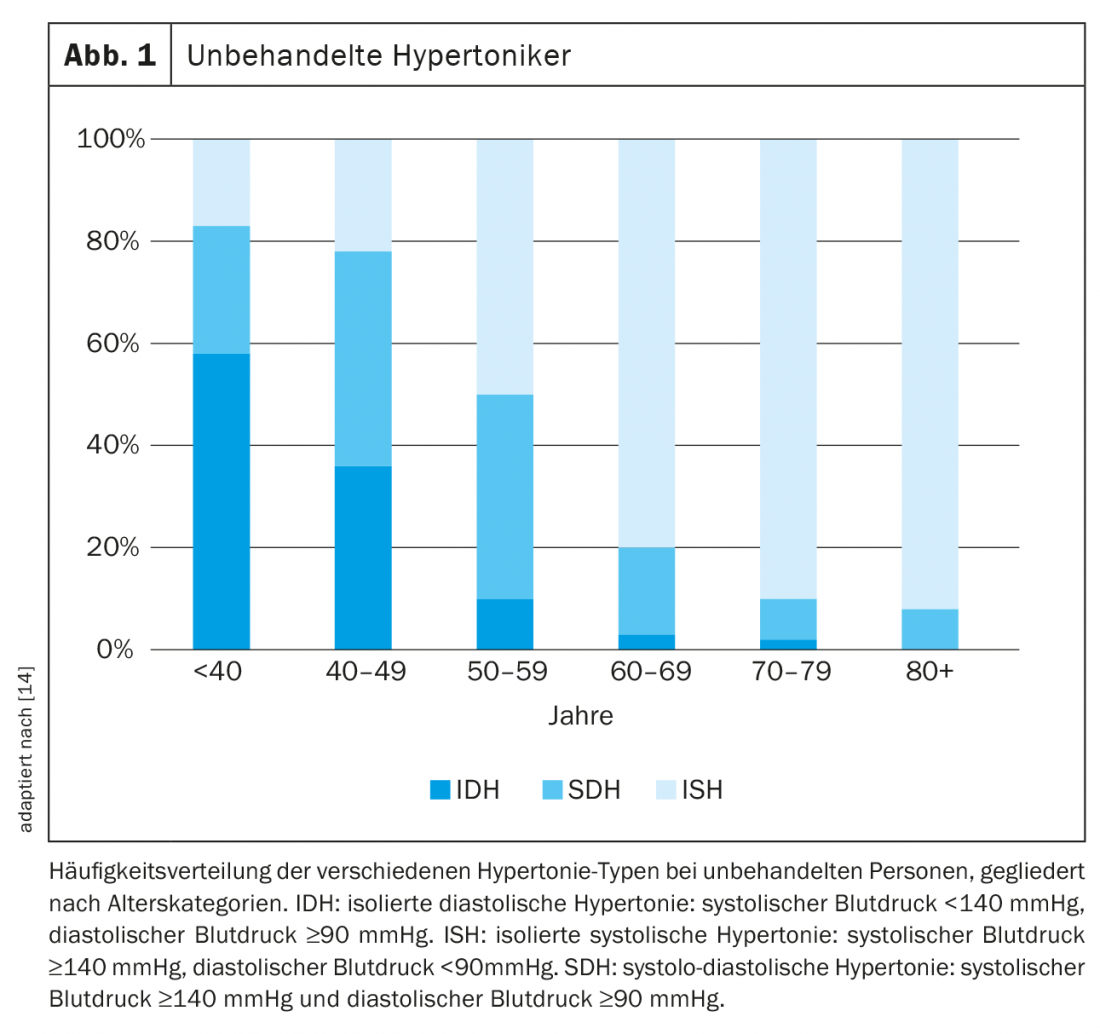

Vascular changes in old age: With age, blood vessels become stiffer and lose elasticity. There is an increase in pulse wave velocity with augmentation of late systolic blood pressure. This leads to an increase of the prognostically important blood pressure amplitude resp. in a corresponding constellation to the occurrence of isolated systolic hypertension. This is significantly more frequent in older age than in young patients with hypertension (Fig. 1) . As a consequence, an age-related increase in systolic blood pressure with decreasing diastolic blood pressure is observed beyond the age of about 60.

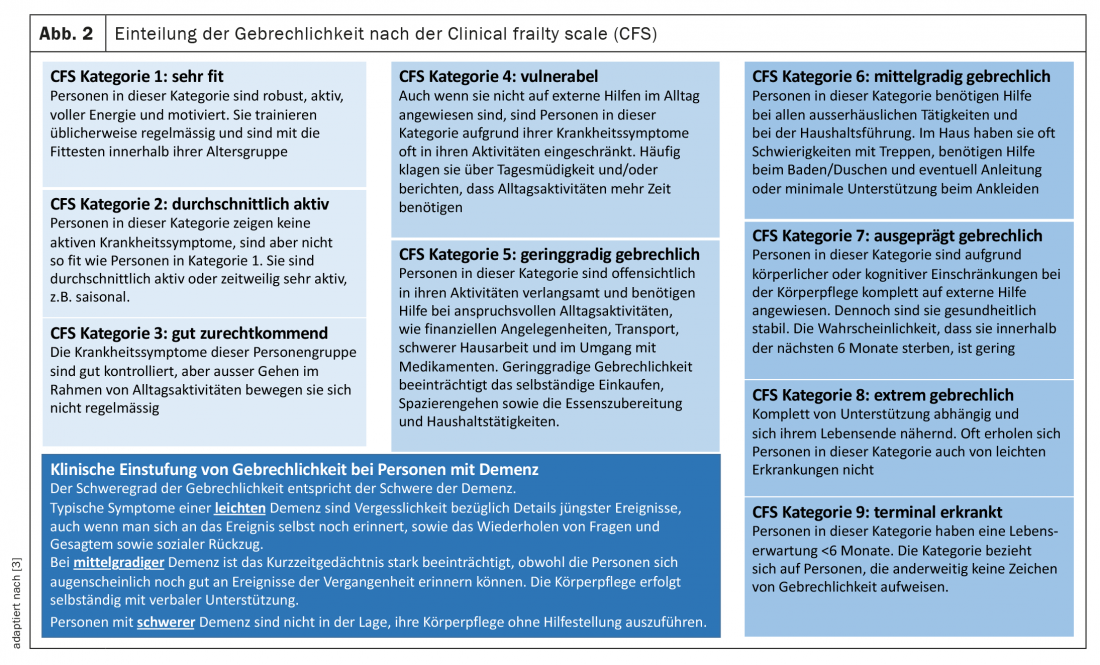

Frailty: Frailty is a multidimensional geriatric syndrome and corresponds to the pathophysiological correlate of functional decline with decrease in physical fitness, often body weight, and sarcopenia. Clinically, frailty can be defined and quantified differently, and a variety of different scores exist. A pragmatic assessment and quantification of frailty allows the clinical frailty scale (CFS) of the Canadian Study of Health & Aging (Fig. 2) [2, 3]. Here, “frail” is used to refer to CFS category 5 and above. The definition of frailty is important when considering and interpreting study results on blood pressure reduction in this important patient population [4].

What to consider when making a diagnosis in elderly hypertensives

White coat hypertension is more common in elderly patients than in young patients [5] and must be ruled out before initiating drug therapy. Medications that increase blood pressure are also taken more frequently by older patients than by younger ones. These include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, antidepressants (venlafaxine, bupropion), or cold medications (pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine). In all elderly patients with arterial hypertension, standing blood pressure measurement (1 and 3 minutes after standing up) should always be performed to avoid missing relevant orthostatic hypotension.

Special features of antihypertensive therapy

Pharmacotherapy in the elderly: elderly patients often suffer from concomitant diseases such as renal insufficiency or atherosclerotic vascular changes [1]. They are more susceptible to side effects of antihypertensive therapy, especially hypotension with/without falls or injury [6]. Possible reasons for this include often inadequate hydration status, reduced baroreceptor sensitivity, altered pharmacokinetics, or increased prevalence of a white coat component [6]. These hypotonias are associated with increased morbidity and mortality due to the altered autoregulatory mechanisms of the different organs [6]. It is therefore indicated in the 2018 European Hypertension Guidelines [1] that in very elderly patients, the recommended initial combination therapy may be deviated from in favor of monotherapy to avoid these side effects. In predisposed patients, loop diuretics and alpha-blockers should be avoided because of the described association with falls [1]. Renal function should be checked regularly, as sufficient antihypertensive therapy (desirably) reduces renal perfusion pressure [1].

Especially during the initiation phase of hypertension therapy, good monitoring for any adverse effects of antihypertensive therapy is essential. These adverse effects are likely to be more common in daily practice than reported in the randomized trials because the trial setting usually dictates close monitoring [1]. On the other hand, medication adherence should be regularly assessed in elderly hypertensive patients, as frailty is an important determinant of nonadherence [7].

Benefit of antihypertensive therapy in elderly, very elderly, and frail patients: The HYVET trial [8] randomized 3845 patients older than 80 years with systolic blood pressure >160 mmHg to therapy with indapamide (+perindopril if needed) or placebo. The treatment goal was a blood pressure <150/80 mmHg. After a median follow-up of 1.8 years, the verum group significantly reduced all-cause mortality by 21%, mortality due to stroke by 39%, and cardiovascular event rate by 34%. Also striking was the significant reduction in heart failure events with antihypertensive therapy. Meta-analyses even showed that elderly patients benefit more from intensive (target systolic 120-140 mmHg) blood pressure lowering than younger patients, and without an increase in side effects [9]. The SPRINT SENIOR study [10] demonstrated significant benefit of antihypertensive therapy even in patients >75 years of age who were classified as “frail” using the 37-point frailty index. Interestingly, neither post-hoc analyses of HYVET nor those of the SPRINT trial found an impact of frailty on the benefit of antihypertensive therapy. However, based on the inclusion criteria of the two randomized trials mentioned above, it is evident that advanced frail patients were not studied or were not included in the study. That the definition of frailty tends to reflect more pronounced comorbidity [4]. Patients from nursing homes, patients with significant cognitive impairment, or reduced autonomy were excluded from most randomized trials of pharmacological blood pressure therapy [2]. Therefore, in the case of very elderly, multimorbid and/or frail patients, a very individualized approach is still necessary. Interesting findings can be drawn from observational studies in this patient population, although observational studies of antihypertensive therapy in advanced frail patients are more difficult to interpret (and perform). A study of a cohort of elderly patients from the general population (frail patients were included) showed that better adherence to antihypertensive therapy was associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular events and mortality even in very old patients (>85 years) [11], highlighting the importance of medication adherence even in old age. A population-based observational study (LEIDEN 85+ study) in very old patients (>85 years) showed that lower systolic blood pressure on antihypertensive treatment with >1 antihypertensive drug, but not untreated, was associated with increased mortality and more rapid cognitive decline [12], which puts aggressive drug lowering of blood pressure in very old age into perspective. A similar conclusion was reached in the PARTAGE study of nursing home residents >80 years [13]. However, reverse causality must be considered when interpreting these results from observational studies [2], i.e., blood pressure decline as an expression of declining health with diminution of prognosis. Despite this difficult to prove reverse causality (respectively, causality of blood pressure lowering with poorer prognosis), impaired autoregulation in very old patients in the context of aggressive blood pressure lowering is quite conceivable as an explanation for the observed higher mortality [2] and underlines the need to individualize blood pressure therapy in the advanced frail.

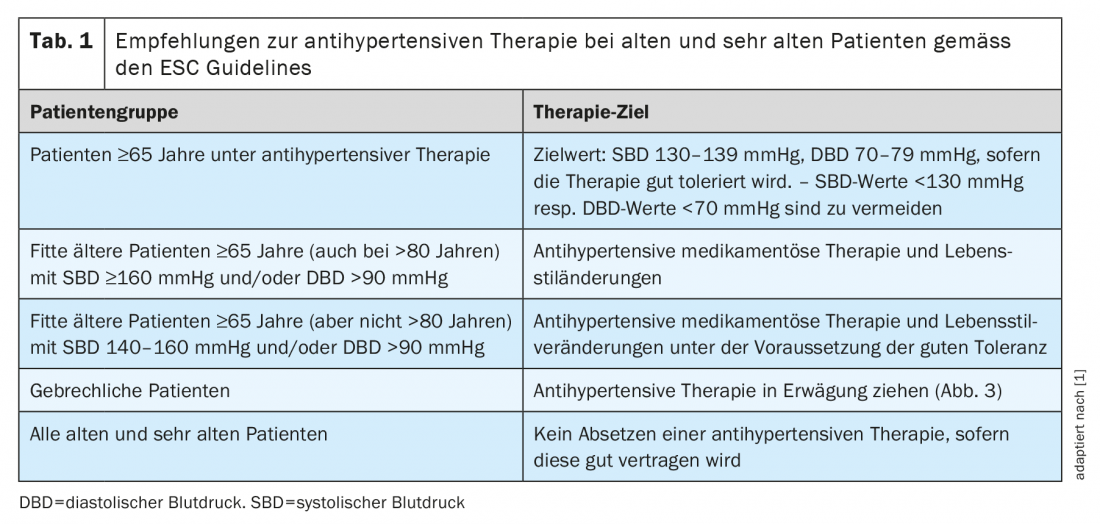

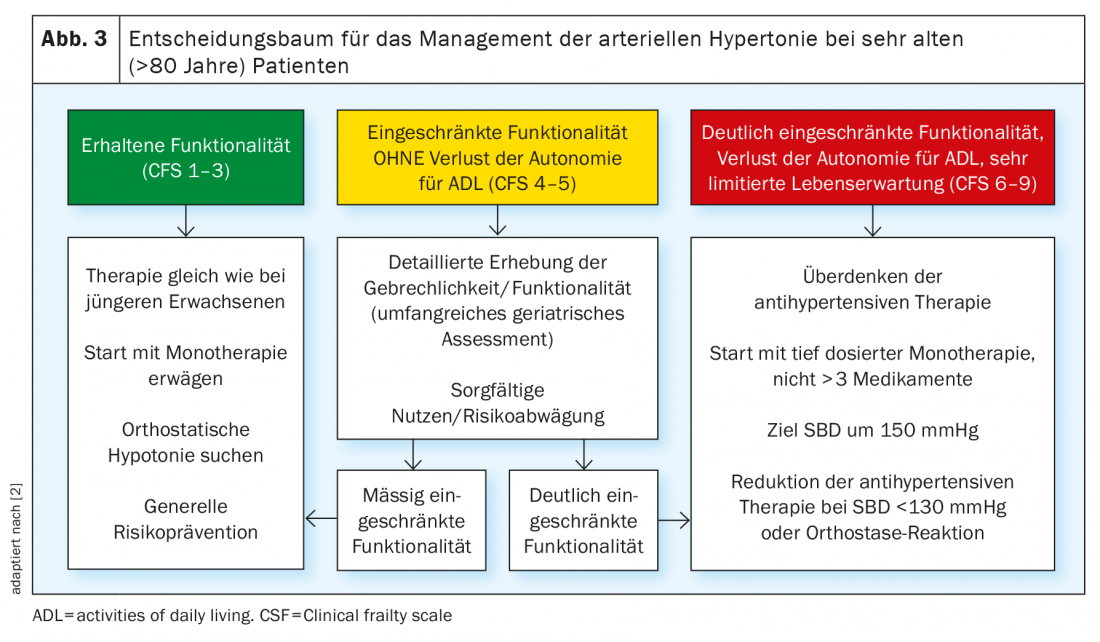

Target blood pressure values and practical approach: Management recommendations for elderly, very elderly, and frail hypertensives are summarized in Table 1 . Target blood pressure values according to the 2018 European Hypertension Guidelines [1] are in the range of 130-139 mmHg systolic and 70-79 mmHg diastolic in elderly and very elderly patients, provided that drug therapy is well tolerated. Blood pressure values <130 mmHg systolic should be avoided [1]. For very elderly patients, the focus is on reducing functional decline and maintaining independence and a good quality of life. Therefore, it is important to avoid side effects of antihypertensive therapy such as orthostatic hypotension, electrolyte disturbances (with repeated blood sampling), and worsening renal function whenever possible. Therefore, individual management strategies arise for these patients, and antihypertensive therapy can generally be considered. A decision algorithm for very old patients is shown in Figure 3. Target blood pressure values should be aimed for only if drug therapy is well tolerated. However, it must be emphasized that even blood pressure lowering that does not achieve its goal has clinical benefit [1]. So the all-or-nothing law does not apply to blood pressure therapy.

Take-Home Messages

- Elderly and very old patients with hypertension tend to be at increased risk for adverse effects of antihypertensive therapy: medication should be started and extended cautiously.

- Sitting and standing blood pressure measurement is part of the procedure in elderly patients to detect orthostatic hypotension and prevent falls.

- In frail patients, the indication or blood pressure target depends on the degree of frailty: the decisive factor is the greatest possible preservation of quality of life.

- In fit elderly and very old patients, a target of 130-139 mmHg systolic and 70-79 mmHg diastolic should be aimed for. It is important that the antihypertensive medication is well tolerated.

Literature:

- Williams B, et al: 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J, 2018. 39(33): 3021-3104.

- Benetos A, Petrovic M, Strandberg T: Hypertension Management in Older and Frail Older Patients. Circ Res, 2019. 124(7): 1045-1060.

- Benziger P, Eidam A, Bauer J: Clinical importance of the detection of frailty. Z Gerontol Geriat, 2021. 54: 285-296.

- Schönenberger A: Hypertension in frail patients. Cardiovasc Med, 2021. 172: w10089.

- Tanner RM, et al: White-Coat Effect Among Older Adults: Data From the Jackson Heart Study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich), 2016. 18(2): 139-145.

- Rivasi G, et al: Hypertension management in frail older adults: a gap in evidence. J Hypertens, 2021. 39(3): 400-407.

- Jankowska-Polanska B, et al: Adherence to pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of frail hypertensive patients. J Geriatr Cardiol, 2018. 15(2): 153-161.

- Beckett NS, et al: Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med, 2008. 358(18): 1887-1898.

- Roush GC, et al: Does the benefit from treating to lower blood pressure targets vary with age? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens, 2019. 37(8): 1558-1566.

- Williamson JD, et al: Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control and Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes in Adults Aged >/=75 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 2016. 315(24): 2673-2682.

- Corrao, G., et al: Protective effects of antihypertensive treatment in patients aged 85 years or older. J Hypertens, 2017. 35(7): 1432-1441.

- Streit S, Poortvliet RKE, Gussekloo J: Lower blood pressure during antihypertensive treatment is associated with higher all-cause mortality and accelerated cognitive decline in the oldest-old. Data from the Leiden 85-plus Study. Ageing, 2018. 47(4): 545-550.

- Benetos A, et al: Treatment With Multiple Blood Pressure Medications, Achieved Blood Pressure, and Mortality in Older Nursing Home Residents: The PARTAGE Study. JAMA Intern Med, 2015. 175(6): 989-895.

- Franklin SS, et al: Predominance of isolated systolic hypertension among middle-aged and elderly US hypertensives: analysis based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. Hypertension, 2001. 37(3): 869-874.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(4): 14-17