New findings from studies have influenced the view towards the two dermatological diseases acne and rosacea in recent years. Among other things, the pathogenesis of acne is now better described and new options for the treatment of stem acne are available. In rosacea, a symptom-based classification of the disease was introduced and the therapeutic goal was adjusted.

New findings from studies have influenced the view towards the two dermatological diseases acne and rosacea in recent years. Among other things, the pathogenesis of acne is now better described and new options for the treatment of stem acne are available. In rosacea, a symptom-based classification of the disease was introduced and the therapeutic goal was adjusted.

Acne represents the most common skin disease worldwide. About 85% of the population is affected once in a lifetime. In adolescents, acne is the most common dermatosis, with a prevalence of 70 to 95%. Acne is often considered a “normal” part of growing up, a quasi-self-limiting condition. However, it is often forgotten how strong the psychological burden is for the acutely affected. In addition, acne can lead to scars from which sufferers suffer for the rest of their lives.

Classification according to clinical picture

Typical skin changes of acne are blackheads (comedones; open/closed), nodules (papules) and pustules (pustules). Based on the clinical picture, a distinction is made between different forms of acne.

- Acne comedonica: Here the clinical picture is dominated by blackheads (comedones), consisting of “black heads” (open blackheads) or “white heads” (closed blackheads). These are mainly located on the nose and forehead.

- Acne papulopustulosa: It is the most common form in teenagers. Especially on the neck and cheeks, papules and pustules appear in addition to comedones.

- Acne conglobata: As the most severe form of acne, it is accompanied by abscess formation as well as severe inflammation with nodules and fistula formation. It occurs on the face as well as on the décolleté and back area. This form often heals with scarring.

Inflammation at the center of pathogenesis

In recent years, it has become clear that a persistent inflammatory response is at the core of acne pathogenesis. It occurs at all stages of the disease – from the initial, invisible microcomedo to the scar (Fig. 1) [1]. The immune system plays a significant role in maintaining inflammation. Thus, overexpression of Toll-Like Receptor (TLR)-2 occurs early on, triggering the inflammatory cascade and tissue degeneration. Over-colonization of the sebaceous glands with Cutibacterium acnes is not the cause of acne, as was once thought. However, it additionally triggers and maintains the inflammatory response by stimulating TLR-2. The inflammatory cascade ultimately leads to secretion of tissue-modulating enzymes, altered collagen remodeling, and thus permanent changes in skin structure in the form of scars: 99% of acne scars derive from inflammatory lesions and post-inflammatory erythema.

Acne therapy: Hit hard and early

For effective improvement and maintenance of the skin’s appearance, therapeutic intervention in the inflammatory cascade must be rapid and targeted. The motto is “Hit hard and early”. This is the only way to reduce acute lesions, prevent recurrences, and address acne scarring preventively. Studies indicate that with early and effective acne therapy, the development of scars can be significantly reduced. Successful treatment of acne involves not only the right choice of medication, but also supporting patients in its correct use.

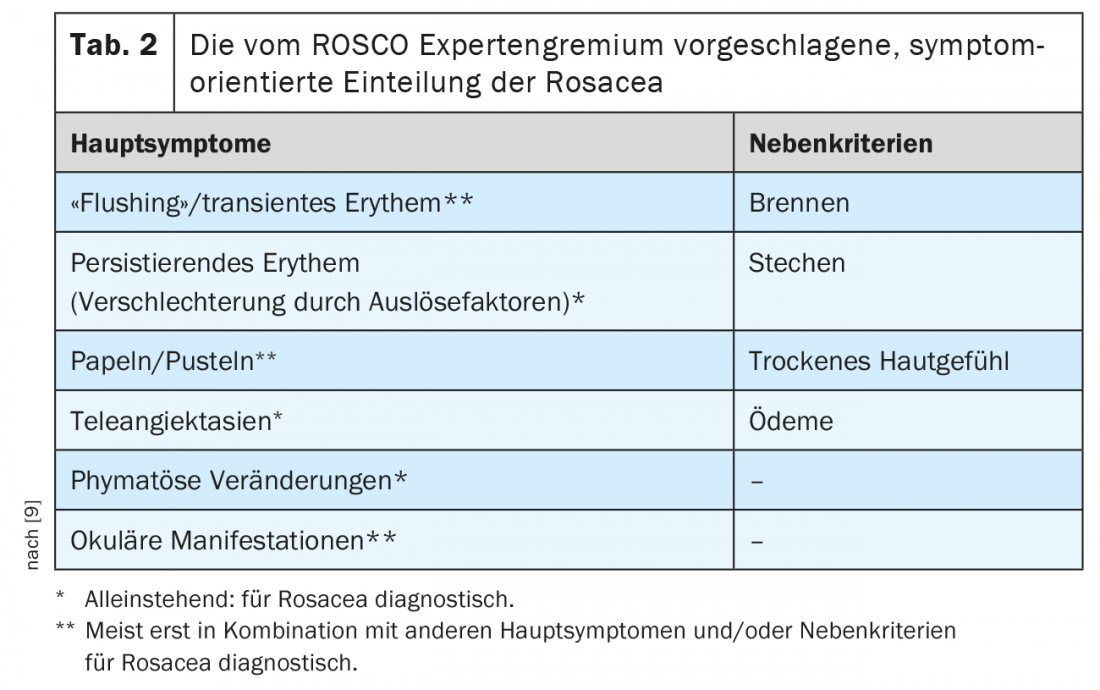

The choice of therapeutic option is based on the severity of acne (Table 1) [2]. Retinoids, benzoyl peroxide and azelaic acid are available, as monotherapy or in the form of (fixed) combinations. A distinction is made between induction and maintenance therapy. Regular monitoring is recommended to maintain compliance and adjust treatment. Therapeutic success is considered to be a reduction of inflammatory lesions by about 50% within three months [2]. If this is not achieved, the therapy must be modified.

New possibility for the therapy of stem acne

A 4th generation retinoid, Trifarotene 0.005%, has recently become available for the treatment of moderate acne with trunk involvement. Trifarotene shows minimal systemic exposure; moreover, there is no systemic accumulation [3]. This makes the cream well suited for the treatment of large areas of the body and thus expands the therapeutic spectrum in the treatment of truncal acne.

Phase III studies have confirmed efficacy, safety and tolerability in facial and upper body acne, including long-term therapy [4,5]. Once-daily use over a 12-week period resulted in a 66% reduction in inflammatory lesions on the face and a 65% reduction on the trunk of the body in patients with moderate acne [4]. In long-term use over 52 weeks, about two-thirds of patients experienced appearance-free or nearly appearance-free skin on the face or trunk [5].

Topical treatment has effect on scars

Furthermore, data from the OSCAR study indicate that the fixed combination of 0.3% adapalene/benzyl peroxide (ADA/PBO) has an effect on pre-existing atrophic acne scars [6]. In the split-face study, patients with primary moderate inflammatory acne were treated with the fixed combination 0.3% ADA/BPO on one half of the face and vehicle on the other half for 24 weeks. Patients had a mean of approximately 40 lesions and 12 acne scars per half of the face. The number of scars decreased under 0.3% ADA/BPO by -15.5% versus baseline, while an increase of atrophic acne scars by 14.4% was observed on the vehicle-treated half of the face. These results indicate stimulation of collagen neogenesis, which can prevent the formation of scars and profoundly improve the skin appearance of existing scars.

Furthermore, the study found that treatment with ADA/PBO also had a preventive effect on acne scarring. Inflammatory lesions reduced by 87% with therapy and the proportion of patients with appearance-free/nearly appearance-free skin was 64%.

Rosacea

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory centrofacial disease characterized by transient or persistent erythema with or without flushing and accompanied by telangiectasias. In more severe cases, pustules and hyperplastic sebaceous glands may develop on the nose and other facial regions [7]. The perioral and periorbital areas are typically left out.

According to the literature, the prevalence of rosacea ranges from 1 to 22%. It is more common in individuals with fair skin type (Fitzpatrick I-II). Women are also affected more often than men (60% vs. 40%). For women, the highest prevalence is in the 61- to 65-year-old age group, and for men, in the 76- to 80-year-old age group. In 80% of cases, diagnosis occurs at age >30 years. The disease places a great burden on those affected. They often take on significant restrictions and behavioral changes to avoid relapses.

Combination of genetics and environmental factors

The etiology of rosacea is not yet fully understood. Genetic predisposition and vascular genesis are discussed. Twin studies found that about half of the risk of rosacea is due to genetics, and the other half is due to exogenous or endogenous triggers. Known trigger factors include especially cold/hot weather, temperature changes, coffee, alcohol consumption, spicy/strongly spiced foods, sunlight, physical activity, psychological stress, and menstruation. In addition, the hair follicle mite Demodex folliculorum appears to play a role in the inflammatory response. Their density is higher in affected individuals than in individuals without rosacea.

Classification into subtypes according to NRS

The American National Rosacea Society (NRS) classification published in 2002 distinguishes between four subtypes of rosacea [8]. In addition, there are also various special forms (e.g. steroid rosacea).

- Subtype 1: Erythemato-teleangiectatic rosacea. Persistent erythema (vasodilatation), more or less pronounced telangiectasia, burning, stinging, itching, “sensitive skin”, dryness/scaling of the affected skin.

- Subtype 2: Papulopustular rosacea. Persistent (over weeks) centrofacial erythema, inflammatory red papules and pustules (usually symmetrical), nodules, fine lamellar scaling.

- Subtype 3: Phymatous rosacea. Connective tissue and sebaceous gland hyperplasia, which manifests locally in the form of nodules, so-called phyma, as well as diffusely.

- Subtype 4: Ocular rosacea. Ocular involvement with conjunctival, corneal and eyelid inflammation occurs in approximately 30 to 50% of rosacea patients. In 20% of cases, ocular symptoms are the initial manifestation.

New, symptom-oriented classification

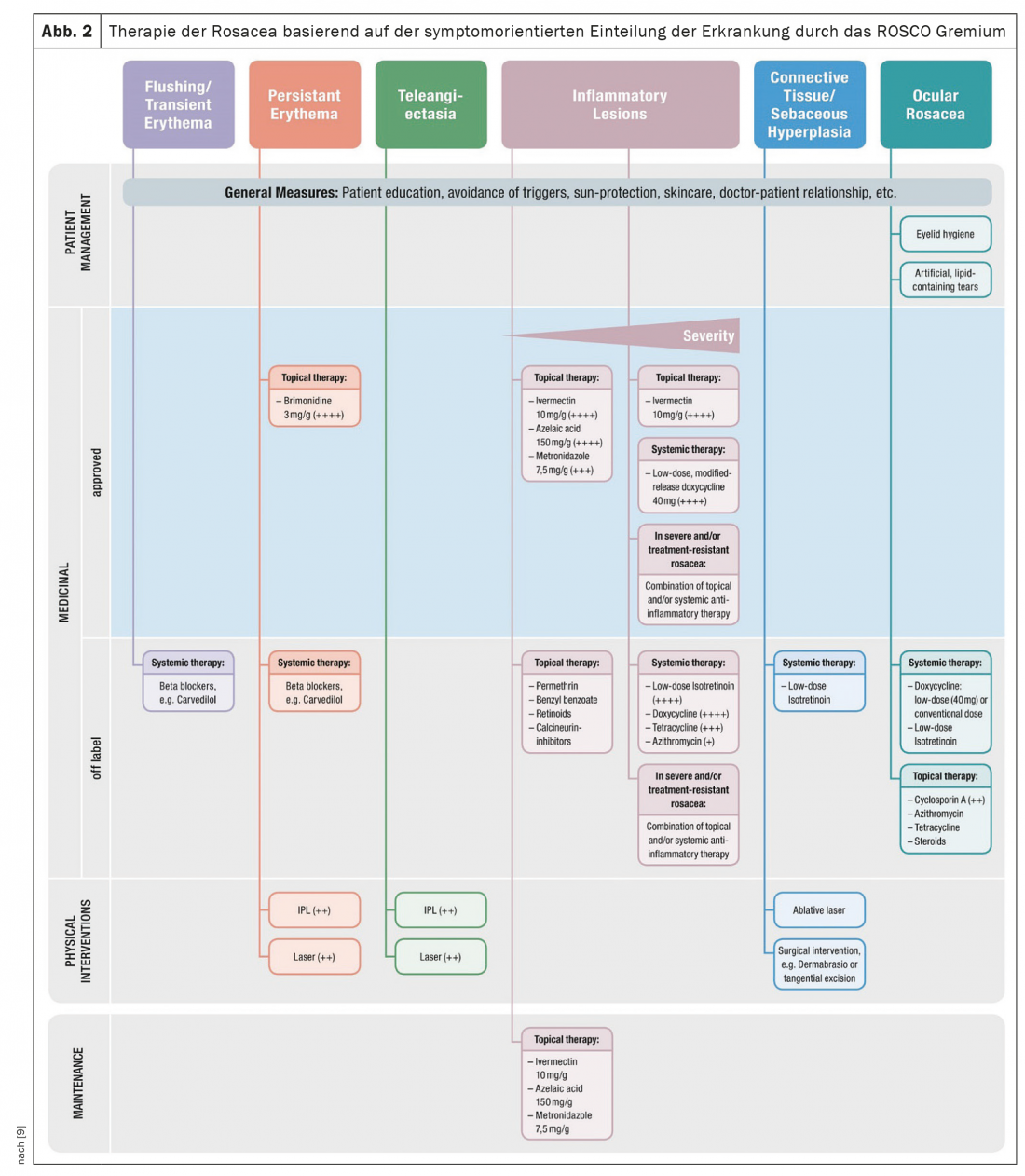

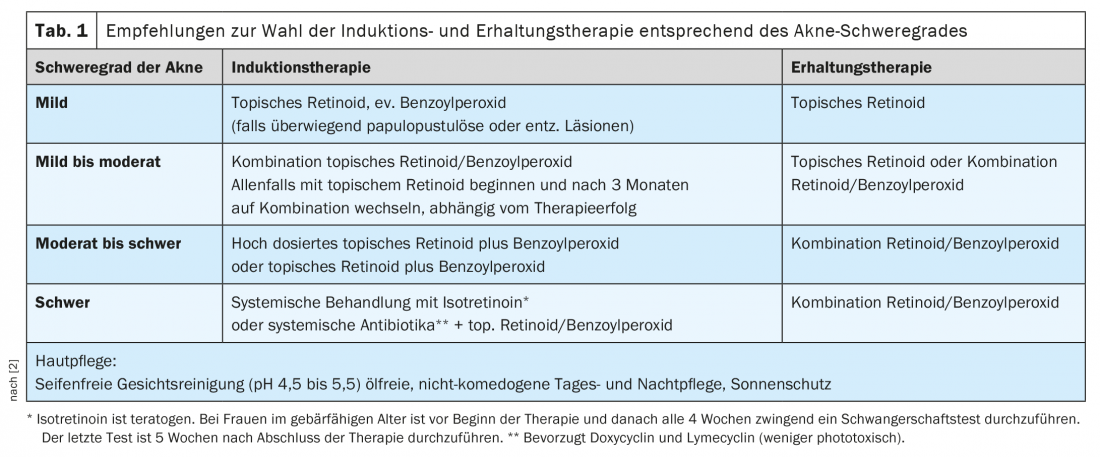

However, rosacea symptoms often occur across subtypes and are associated with each other. In addition, the NRS classification is not well suited as a basis for treatment decisions. Therefore, the ROSCO (ROSacea COnsensus) expert panel has proposed a symptom-based classification (Table 2) [9]. A distinction is made between main symptoms and secondary criteria. The main symptoms are decisive for the choice of therapy.

Topical treatment in the center

Topical therapy is at the heart of the treatment of rosacea. Based on the symptom-based classification of the disease by the ROSCO panel, brimonidine, ivermectin, metronidazole, or azalaic acid are used for this purpose (Fig. 2) [9]. Doxycycline may be used for systemic therapy. In addition, management of patients with rosacea includes adjunctive measures such as patient education, avoidance of triggers, sun protection and skin care, and the use of physical or surgical therapy options when indicated.

Therapy goal: completely appearance-free skin

The goal of rosacea treatment is complete freedom from appearance (Investigator Global Assessment [IGA] 0). A reanalysis of previously published clinical trial data (CLEAR study) underscored the importance of achieving this goal [10]. The CLEAR study examined whether there were differences between appearance-free and near-appearance-free patients in terms of quality of life and time to a new rosacea episode in 1366 patients with mild to severe rosacea.

It was found that patients whose treatment outcome was described as “completely free of appearance” (IGA 0) remained free of recurrence for at least five months longer after the end of therapy than patients who were only classified as “almost free of recurrence” (IGA 1) had reached. In addition, IGA-0 patients recorded a better quality of life. Advantages in terms of achieving freedom from manifestations were seen for ivermectin over metronidazole (35% vs. 22%).

Take-Home Messages

- Acne is an inflammatory dermatosis.

- Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) plays a central role within the inflammatory cascade in acne.

- Trifarotene 0.005%, a therapy specifically approved for stem acne, is now available.

- A classification of rosacea based on the clinical picture facilitates the choice of therapy.

- The therapeutic goal in rosacea is complete freedom from symptoms. This also reduces the risk of recurrence.

Literature:

- Dréno B, et al: Understanding innate immunity and inflammation in acne: implications for management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29(Suppl. 4): 3-11.

- Läuchli S, et al: Swiss Practice Recommendations for the Treatment of Acne. Derm Hel 2020; 32: 28-33.

- Specialized information Aklief cream (Trifarotene). www.swissmedicinfo.ch.

- Tan J, et al: Randomized phase 3 evaluation of trifarotene 50 μg/g cream treatment of moderate facial and truncal acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 1691-1699.

- Blume-Peytavi U, et al: Long-term safety and efficacy of trifarotene 50 μg/g cream, a first-in-class RAR-γ selective topical retinoid, in patients with moderate facial and truncal acne. JEADV 2020; 34: 166-173.

- Dréno B, et al: Prevention and Reduction of Atrophic Acne Scars with Adapalene 0.3%/Benzoyl Peroxide 2.5% Gel in Subjects with Moderate or Severe Facial Acne: Results of a 6-Month Randomized, Vehicle-Controlled Trial Using Intra-Individual Comparison. Am J Clin Dermatol 2018; 19: 275-286.

- Anzengruber F, et al: Swiss S1 guideline for the treatment of rosacea. JEADV 2017; 31: 1775-1791.

- Wilkin J et al: Standard classification of rosacea: Report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46: 584-587.

- Tan J, et al: Updating the diagnosis, classification and assessment of rosacea: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 431-438.

- Webster G, et al: Defining treatment success in rosacea as “clear” may provide multiple patient benefits: results of a pooled analysis. J Dermatolog Treat 2017; 28: 469-474.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2021; 31(5): 4-8