With the introduction of the DSM-5 and the accompanying expansion of the inclusion criteria, the differentiated clinical diagnosis takes on even greater importance. This is against the background of missing biomarkers on the one hand and psychometric instruments that have not yet been adapted to the modified diagnostic manual on the other. It remains to be seen whether the good agreement in diagnosing (interrater reliability kappa 0.61), which has been achieved so far in comparison to other mental disorders, can be maintained under these conditions [1]. In comparison, therapeutic options have changed little in recent years. In Switzerland, Atomoxetine® was approved as a second-line treatment for ADHD that has persisted since childhood, effective October 1, 2015. Consensus remains on the need for a multimodal approach (combination of psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions).

ADHD is a neuropsychiatric disorder that usually first manifests in early childhood, when the social functioning of affected children and adolescents is increasingly negatively affected by the core symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity [2].

ADHD occurs in approximately 5% of children and 2.5% of adults in most cultures, with males more commonly affected than females in a ratio of approximately 2:1 in children and 1.6:1 in adults [3]. According to current research, ADHD symptoms persist into adulthood in over 50% of affected children. Depending on the severity of the symptom expression as well as the life phase of the affected person, ADHD can lead to significant restrictions in a variety of areas of life, e.g. with regard to health, partnership, education, work situation and finances. The diagnostic procedure is further complicated by the high rate of comorbidities – figures of up to 80% are cited here [4]. From the psychiatric field, affective disorders, substance abuse and personality disorders, but also anxiety disorders are of particular importance. Somatic problems include difficulty with planning, time management, and general organization of routines: Adults with ADHD are less likely than the general population to participate in preventive measures and are also less likely to take care of their physical well-being, contributing to an increased risk of infections, cardiovascular disease (2.4-fold), cancer, and dental problems compared to healthy controls [2,5]. As with most other mental disorders, ADHD is a clinical diagnosis.

Diagnostic features according to DSM-5

The introduction of the DSM-5 resulted in a number of changes for the disorder of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, the most important of which will be briefly reviewed below:

- Symptoms that occurred at a later age – the “age of onset” is now defined as the twelfth year of life – are now also taken into account. Until now (DSM-IV), this limit was at the age of seven. In contrast, the consistent pattern of “multiple symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity” remained unchanged [3].

- For young adults aged 17 and older, five (instead of the previously required six) symptoms from the areas of inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity are now sufficient to make the diagnosis. At least two areas of life were to be affected by the impairments, whereby the number of defined symptoms, nine each for inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity, remained unchanged.

- No distinction is made between the three different types or subtypes, but for possible further differentiation, “appearances” – in the original English text, “presentations” – are used. Accordingly, the following manifestations and their expression according to severity (mild, moderate to severe) as well as the degree of remission (“partial remission”) should be determined:

- F90.2 mixed appearance

- F90.0 predominantly inattentive appearance

- F90.1 predominantly hyperactive-impulsive appearance

- Furthermore, an autism diagnosis/PDD (“pervasive developmental disorder”) is no longer an exclusion criterion according to DSM-5.

Clarification and testing procedures

Currently, there is no established genetic biomarker for ADHD despite its high heritability of 70-80% [6]. Accordingly, they are not mentioned in the guidelines or in the DSM-5. Although some authors have high hopes for pharmacogenetic tests or, for example, EEG-ERP, these have hardly been validated so far.

A central cornerstone of the diagnostic process therefore continues to be the thorough anamnesis. In particular, accurate recording of early childhood development and school years is important [7]. In this context, the information provided by the parents and the documentation of involved educators (school reports) are of particular importance and should, if possible, be requested and included in the diagnostic considerations.

A well-founded and timely diagnosis can have a relieving effect, especially for young adults and their social environment, and help to set a more targeted course with regard to education and career choices.

The consideration of different severity and remission levels (according to DSM-5) will not only contribute to a better understanding of the heterogeneity of this disorder, but will also allow to give a clearer picture of deficits and resources as well as of the functional picture of the affected person to possible service providers (e.g. insurance companies).

A precise somatic history and the exclusion of possible organic causes from the internal or neurological field (e.g. hyper- or hypothyroidism or neurofibromatosis) are further important aspects of a guideline-based ADHD diagnosis in addition to a comprehensive substance and medication history [8].

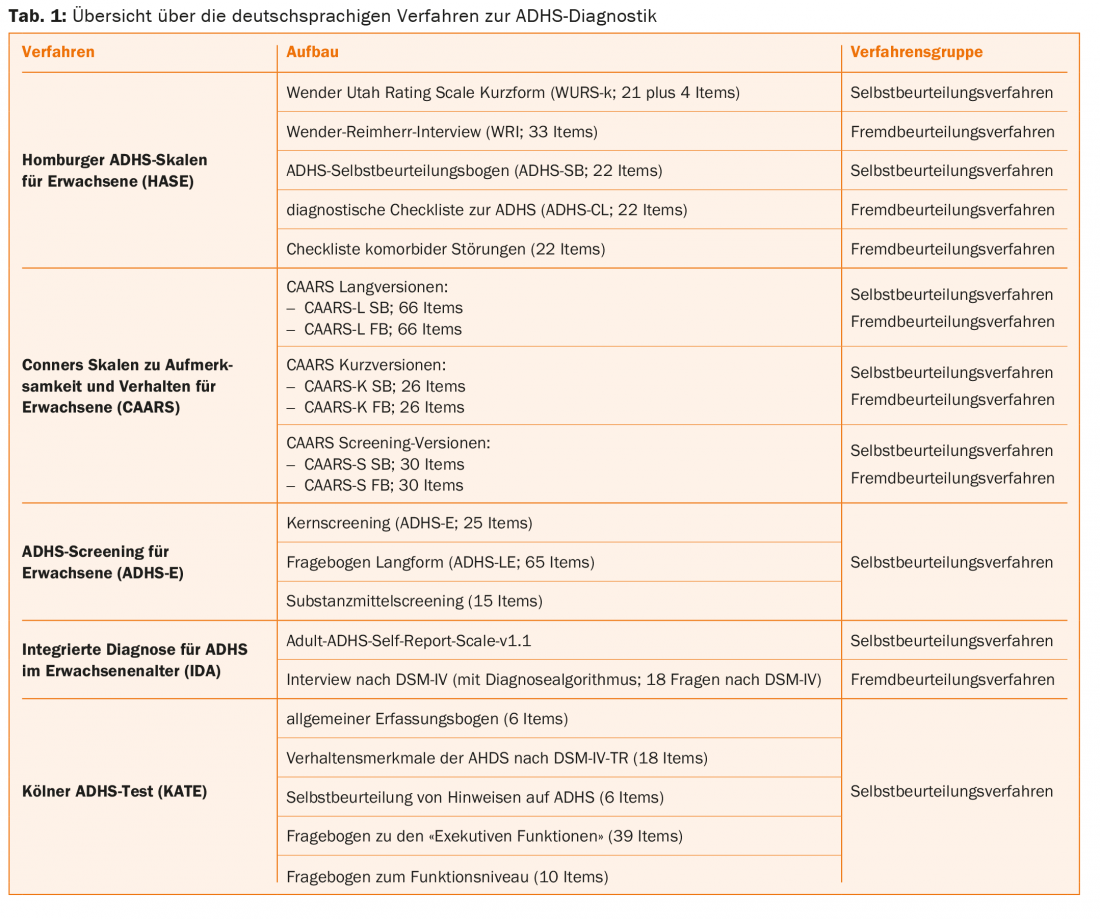

Several checklists and structured interviews in self- and external assessment procedures can be consulted for symptom recording and evaluation of the diagnostic criteria of ADHD according to ICD-10 or DSM-IV/-5. An overview of the German-language procedures for ADHD diagnostics is shown in table 1 . The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) was developed and authorized by the WHO and is based on a pure self-report procedure. Both the Homburger Adult ADHD Scales (HASE) and the Conners’ Adult Attention-Deficit Rating Scale contain self- and other-assessment procedures. As a measurement instrument for retrospective assessment of early childhood symptomatology (still according to DSM-IV, age between eight and ten years), the HASE contains the WURS-k (21 plus 4 items), which is also available as a long version with 61 items.

A freely available structured interview based on the DSM-IV (18 criteria), translated into 16 languages, which can be applied across childhood and adulthood, should not go unmentioned here. This is the DIVA 2.0 (diagnostic interview for ADHD in adults), which, unlike most of the other instruments mentioned, can be downloaded free of charge from the homepage www.divacenter.eu or via app [9].

In addition, it should be noted that the time required for the use of the individual methods is roughly comparable, but should not be underestimated in everyday clinical practice [10]. In particular, obtaining the most objective, third-party medical history possible can be a significant challenge.

The M.I.N.I (Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview), a short structured interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10, has proven useful for assessing comorbidities [7,11]. Also suitable for the assessment of further psychopathology is the SCL-90-R (Symptom Checklist 90-Revised), which is a 90-item self-report inventory and from which the presence of ADHD may also be inferred [12].

Therapy

The diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood does not imply the need for treatment. In this case, the individual suffering pressure remains decisive for the decision for or against admission to therapy. It is recommended that treatment should only be initiated “when there are marked disturbances in one area of life or mild disturbances or pathological, disabling psychological symptoms in several areas of life and these can be clearly attributed to ADHD” [13].

Psychoeducation is also a key component of ADHD therapy [14]. In clinical practice, inquiring about the motivation for therapy – intrinsic or extrinsic – can provide helpful clues about the expected compliance of young adults. In some cases, the pressure of suffering may be greater in the patient’s environment than in the affected person himself, since the parents or partners contribute to compensation and thus to masking the symptomatology.

Today, guideline-compliant therapy for ADHD is multimodal, combining both psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic approaches and taking into account comorbid disorders.

According to the 2008 and 2012 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, the following aspects should be included in the considerations when selecting an appropriate preparation [15]:

- Patient preferences

- Comorbidities (anxiety disorders, affective

- disorders, dependency disorders)

- Risk of “diversion” or misuse of medication.

- Treatment adherence

- Reduction of stigma (single dose)

- pharmacokinetic profile

- Tolerance and side effects

- Dosing advantages (single dose/delayed release).

Pharmacotherapy

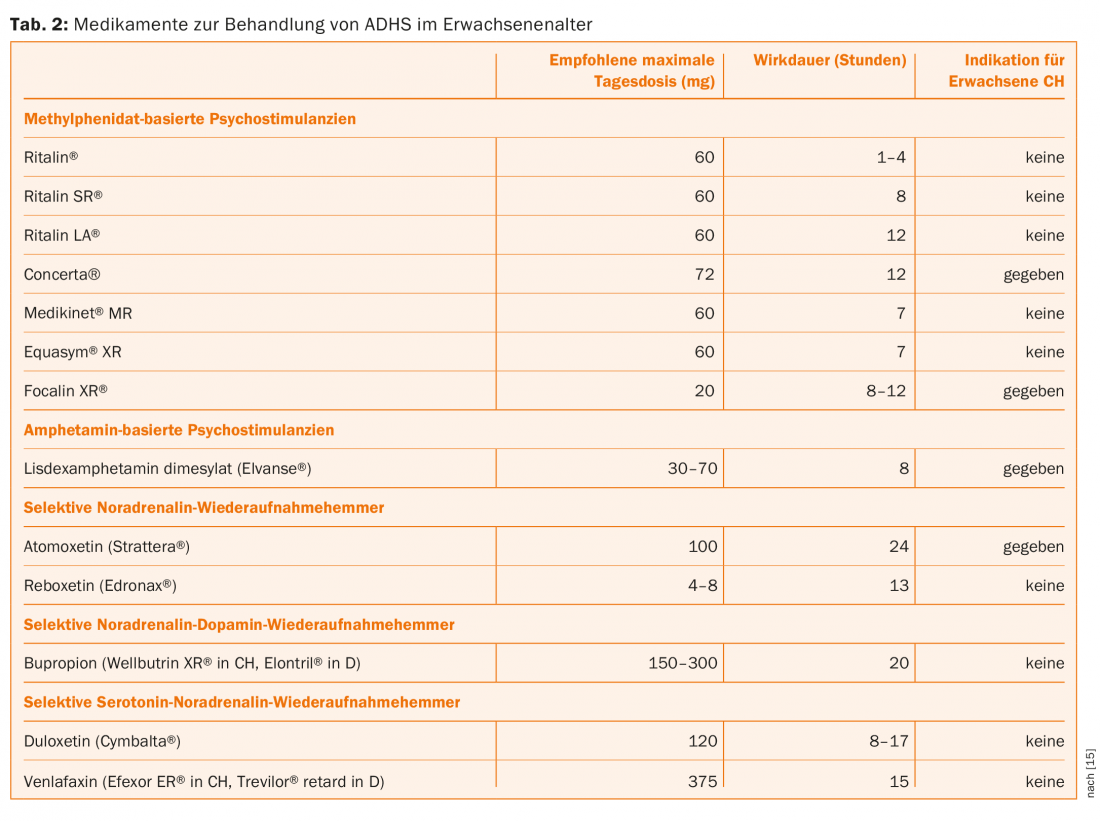

Due to space limitations, we will only briefly discuss pharmacotherapeutic options and instead refer to Table 2. The following groups of medications are available for the treatment of ADHD in adults:

- Psychostimulants represent first-line medications.

- Ritalin®, Concerta®, Medikinet®, Equasym® and Focalin® are based on methylphenidate or dexmethylphenidate.

- Elvanse® (lisdexamphetamine) is so far the only amphetamine-based approved pharmaceutical in Switzerland (no approval in Germany and Austria) (03/2014).

- Non-psychostimulants, which include preparations from the tricyclic antidepressant group, the SSRIs, the SNRIs, and the SNDRIs, have no indication in ADHD and can only be used in an off-label use sense or to treat comorbidities.

- Atomoxetine (Strattera®), as the only non-stimulant substance, has been available in Switzerland since Oct. 1. In 2015, approval for the therapy of ADHD in adults up to 50 years of age (no approval in Germany and Austria).

Literature:

- Freedman R: The initial field trials of DSM-5: new blooms and old thorns. American Journal of Psychiatry 2013; 170(1): 1-5.

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Fischer M: ADHD in adults: what the science says. The Guilford Press: New York/London 2008.

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM-5. 2003.

- Kessler RC, et al: The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The American Journal of Psychiatry 2006; 163(4): 716-723.

- Barkley RA: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Jones & Bartlett Publishers: Boston/Toronto/London/Singapore 2010.

- Faraone SV, et al: Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry 2005; 57(11): 1313-1323.

- Stieglitz RD, Rösler M: Diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood: a review. Journal of Psychiatry, Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2015; 63: 7-13.

- Hyman SL, Shores A, North KN: The nature and frequency of cognitive deficits in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology 2005; 65(7): 1037-1044.

- Kooij JJS: Adult ADHD. Diagnostic assessment and treatment. 3rd ed. Springer: London 2013.

- Schmidt S, Petermann F: ADHD across the lifespan – symptoms and new diagnostic approaches. Journal of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Psychotherapy 2011; 59(3): 227-238.

- Sheehan DV, et al: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1998; 59: 22-33.

- Eich D, et al: A new rating scale for adult ADHD based on the Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90-R). European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 2012; 262(6): 519-528.

- Ebert D, Krause J, Roth-Sackenheim C: ADHD in adulthood – guidelines based on an expert consensus supported by the DGPPN. Neurologist 2003; 74(10): 939-945.

- Safren SA, et al: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated adults with continued symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2005; 43(7): 831-842.

- Eich-Höchli D, Seifritz E, Eich P: Pharmacotherapy for ADHD in adults: a review. Journal of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Psychotherapy 2015; 63: 15-24.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(1): 24-27.