Clostridium difficile is a common cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis. The incidence is increasing. Recurrent forms of the disease in particular lead to a high burden of disease.

According to epidemiological data published in 2017, toxigenic strains of Clostridium difficile (C.difficile) are present in up to 15.5% of hospitalized patients with mortality rates ranging from 3% to 14% [2]. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea is C. difficile associated diarrhea in 10-20% of cases. Onset of symptoms hours to weeks after antibiosis is typical, and prevalence varies depending on the agent used (ampicillin 5-10%; amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 10-25%; cefixime 15-20%; others such as cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, tetracycline 2-5%), among others, the speaker said [3]. The risk of recurrence after a first successfully treated episode is about 20% and increases to 40-60% after the second episode, explains Prof. Ansgar W. Lohse, MD, Clinic Director and Specialist in Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf [1,3].

Diagnostics: What do current guidelines recommend?

According to Professor Lohse, classic clinical features of C.difficile infection (CDI) are the following: watery diarrhea (rarely bloody), fever (28%), abdominal pain (22%), ileus, toxic megacolon, intestinal perforation, sepsis [3]. For diagnostic workup, the following risk factors may be indicative of possible CDI as a tentative diagnosis if symptoms are present: antibiotic therapy (cephalosporins, quinolones, clindamycin, clavulanic acid); proton pump inhibitors; immunosuppression; age>65 years; colonization with C. difficile (0-3% in non-hospitalized individuals; 20-40% in hospitalized patients; chronic inflammatory bowel disease [2–4].

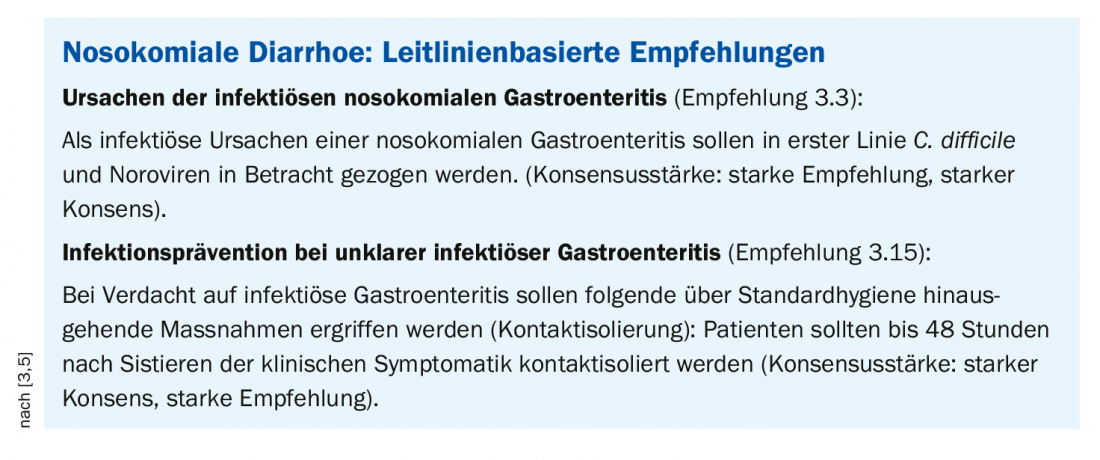

According to the S2k guideline, gastrointestinal C. difficile and noroviruses are possible causes of nosocomial gastroenteritis; other pathogens are irrelevant and do not need to be tested, the speaker explained. As a precautionary measure, patients should be isolated from contact for up to 48 hours after the onset of clinical symptoms if infectious gastroenteritis is suspected (box) [3,5]. The speaker added that 48 h after symptom cessation, de-isolation could be performed without retesting [3].

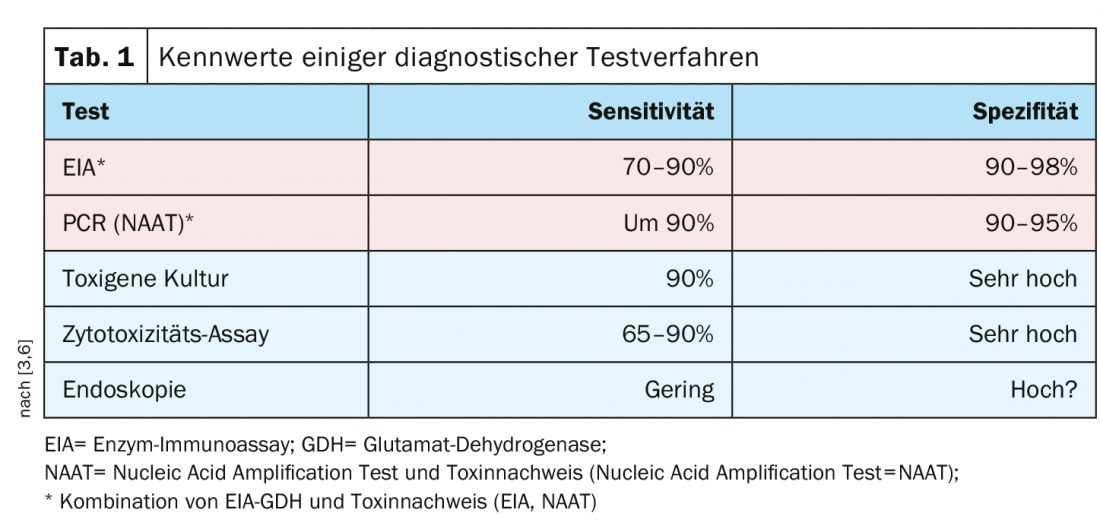

There are several test methods with high sensitivity and specificity, and a combination of enzyme immunoassay/glutamate dehydrogenase (EIA-GDH) and toxin detection (enzyme immunoassay=EIA; nucleic acid amplification test=NAAT) is recommended (Table 1).

Vancomycin is now considered first-line therapy

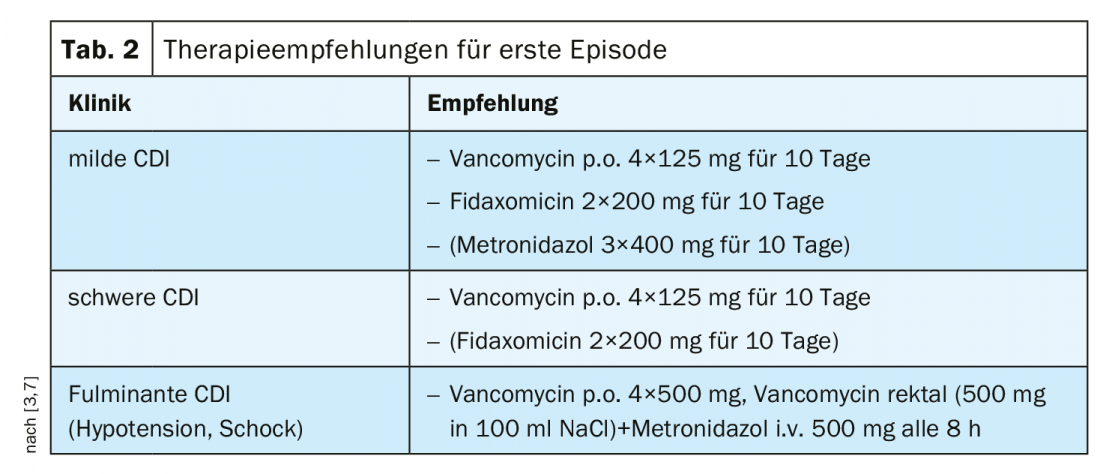

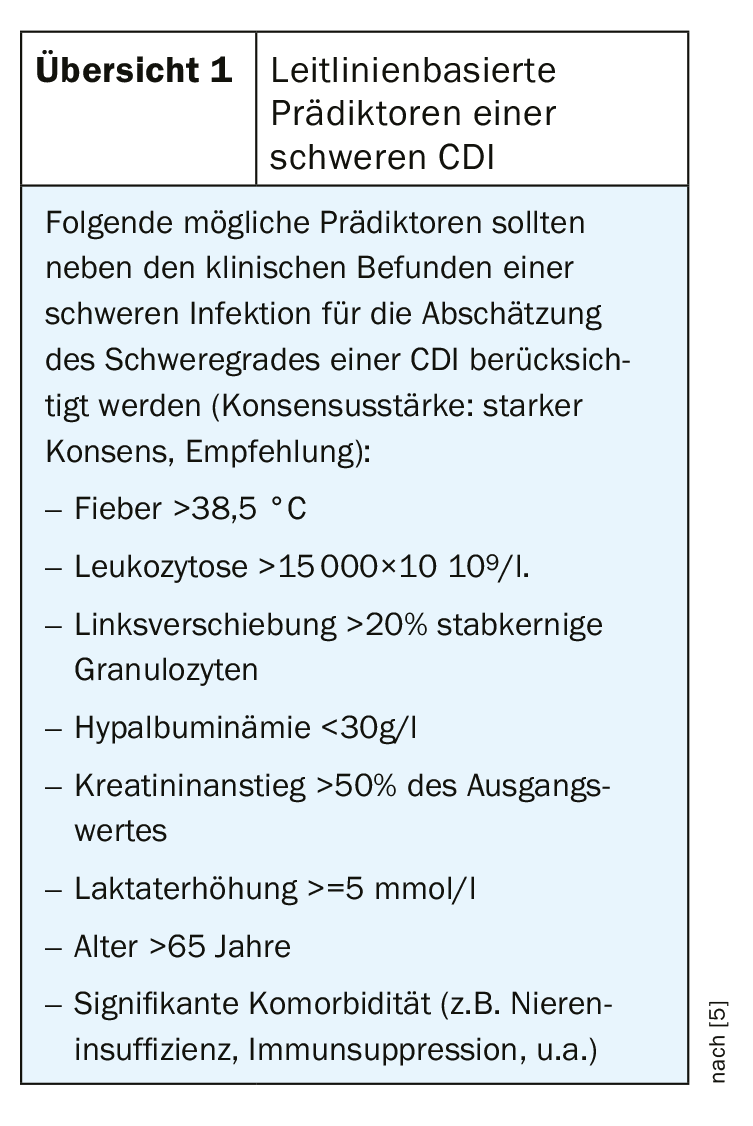

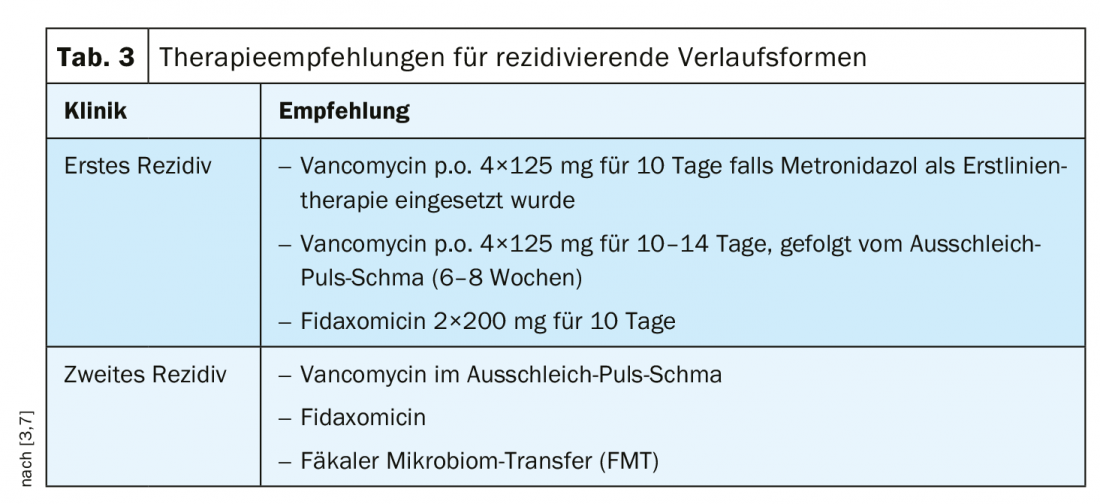

Previously, metronidazole was recommended for mild to moderate CDI as a cost-effective treatment [1]. Vancomycin has been used in cases of intolerance to metronidazole and/or increased risk of recurrence [1]. Based on relevant study findings, the recommendation was adjusted according to 2018 IDSA/SHEA guidelines depending on the severity of CDI [1]. According to current consensus recommendations, vancomycin is considered first-line therapy for both mild and severe degrees of CDI in first-time CDI (Tab. 2). In cases of mild CDI and risk of recurrence, fidaxomicin can be used; contrary to previous assessments, the use of metronidazole should be limited to cases of lack of availability or intolerance of the other two agents [7]. In severe forms and complicated courses of CDI, vancomycin should always be used as first-line treatment [3]. Predictors of severe CDI according to the S2k guideline can be seen in overview 1. Vancomycin or fidaxomicin can be used for therapy of recurrent CDI [3,7] (Table 3).

Relapse prophylaxis very important

Data show that even after successful treatment with achievement of symptom freedom, relapse occurs in a substantial proportion of patients and the risk of relapse increases with each relapse [8]. The temporal criterion for a relapse is a recurrence of symptoms in the period of at least two weeks to at most two months after improvement of the initial symptoms (new infection vs. re-infection), according to the speaker [3].

In the two randomized placebo-controlled trials MODIFY I and MODIFY II, concomitant administration of a single dose of bezlotoxumab (10 mg per kilogram body weight) during standard therapy (vancomycin, metronidazole, or fidaxomicin) for C. difficile resulted in 38% reduction in recurrence rate within 12 weeks [9].

In Switzerland, bezlotoxumab, a monoclonal antibody with high affinity to C. difficile toxin B, has been approved for the prevention of Clostridioides difficile recurrences since late 2017. Bezlotoxumab is directed against the C. difficile toxin B. Another option for relapse prophylaxis with a high success rate is fecal microbiome transfer (FMT) [2,3,12].

There are emerging research findings on preventive strategies, such as use of probiotics, intestinal microbiommaniulation during antibiosis, vaccination, as well as new antibiotics that reduce the negative impact on the intestinal microbiome [1]. Regarding the vaccination option, a phase III trial is still in the recruitment phase until 2020 [3,13].

Source: DGIM, Wiesbaden (D)

Literature:

- Dieterle MG, Rao K, Young VB: Novel therapies and preventative strategies for primary and recurrent Clostridium difficile infections. Special Issue: Antimicrobial Therapeutics Reviews 2019; 1435 (1): 110-138.

- Solbach P, Dersch P, Bachmann O: Individualized treatment strategies for Clostridium difficile infections [Article in German]. Internist (Berl) 2017; 58(7): 675-681. doi: 10.1007/s00108-017-0268-2.

- Lohse A: Slide presentation, DGIM 2019, 05.05.2019, Acute abdomen: presentation 1: C. diff. Colitis, Prof. Dr. med. A. Lohse, Clinic Director, Specialist in Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf.

- Gould LH, Limbago B: Clostridium difficile in food and domestic animals: a new foodborne pathogen. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 51(5): 577-582. doi: 10.1086/655692.

- AWMF: Gastrointestinal infections and Whipple’s disease, S2k guideline 2015, AWMF online. The portal of scientific medicine, registration number 021-024, as of Jan. 31, 2015 , valid until Jan. 30, 2020. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/021-024.html, last accessed May 15, 2019.

- Manthey CF, Eckmann L, Fuhrmann C: Therapy for Clostridium difficile infection – any news beyond Metronidazole and Vancomycin? Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology 2017; 10 (11). www.tandfonline.com, last accessed May 15, 2019.

- McDonald LC, et al: Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin. Infect Dis 1018; 66: e1-e48.

- Deshpande A, et al: Risk factors for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015; 36: 452-460.

- Wilcox MH, et al: Bezlotoxumab for Prevention of Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(4): 305-317.

- Curry SR, et al: High frequency of rifampin resistance identified in an epidemic Clostridium difficile clone from a large teaching hospital. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48: 425-429.

- Muller L, Halfmann A, Herrmann M: [Current data and trends on the development of antibiotic resistance of Clostridium difficile]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Health Research Health Protection 2012; 55: 1410-1417.

- Van Nood, E: Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. NEJM 2013; 368(5): 407-415.

- Pfizer Inc: Clostridium difficile vaccine efficacy trial: NCT03090191. www.pfizer.com/science/find-a-trial/nct03090191, last accessed May 15, 2019.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(6): 32-33 (published 5/24/19, ahead of print).