In the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus, the last few years have brought several innovations with regard to diagnosis, therapy goals, and choice of antidiabetic drugs. “A patient centered approach” are the keywords of the joint position paper of the American and European diabetes societies, which proposes a stronger individualization of therapy goals regarding glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors [1]. Diabetes duration, patient age, hypoglycemia risk, comorbidities, and compliance should be considered when determining treatment goals. Implementation of lifestyle modifications remains the most important measure in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. The available antidiabetic agents allow therapy to be tailored to the patient’s needs and comorbidities. However, the growing number of antidiabetic drugs also requires constant training and experience for the treating physicians. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the goals and treatment options for patients with type 2 diabetes.

HbA1c was newly introduced as a diagnostic criterion for diabetes in 2009. It is less sensitive than fasting blood glucose, but is a practical tool because of its time-of-day independent testing. The diagnostic criteria for pre- and manifest diabetes mellitus are listed in Table 1. Screening is suggested in all patients 45 years of age and older and in overweight individuals with a BMI ≥25 kg/m2 with an additional risk factor for diabetes mellitus [1].

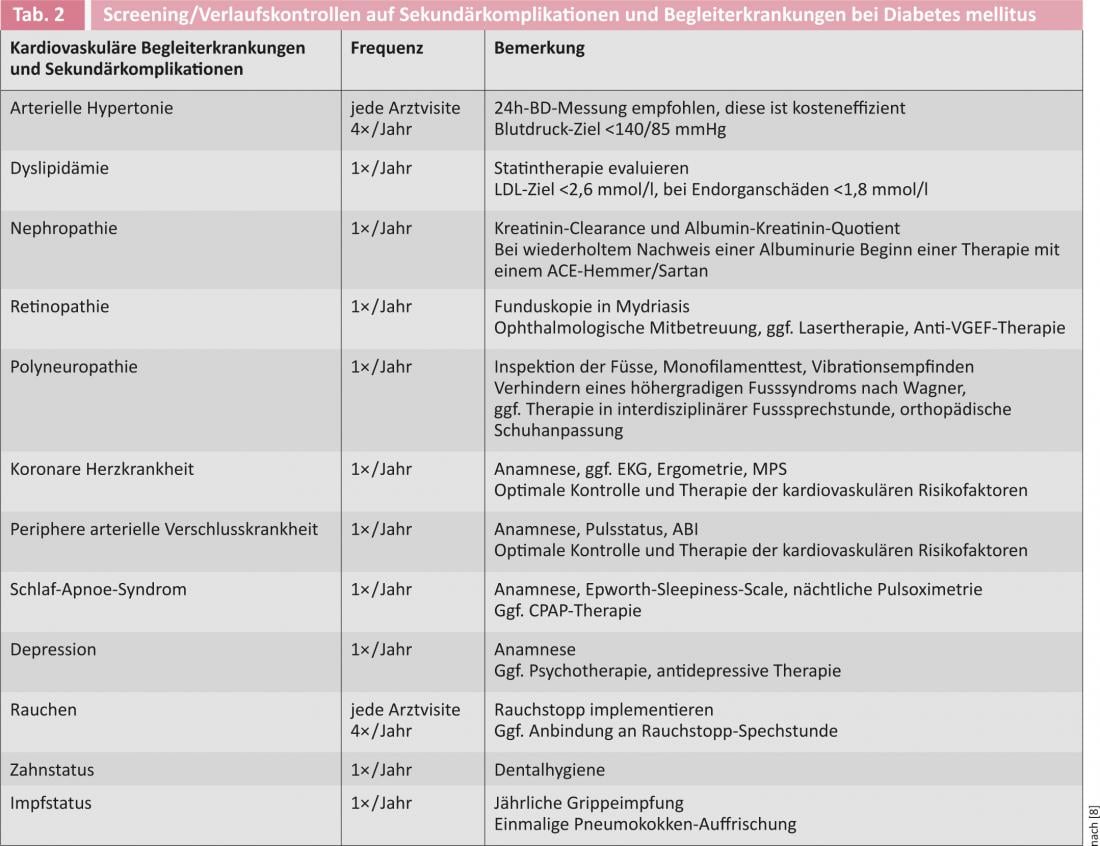

Since a glucose tolerance disorder usually existed for years when diabetes mellitus was first diagnosed, screening for diabetes-associated secondary complications and cardiovascular comorbidities is recommended at the time of diagnosis (Table 2) . Screening should be repeated at annual intervals.

Therapy goals

Large clinical trials such as the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) or the Steno-2 study have shown that optimal glycemic control, together with treatment of the other cardiovascular risk factors, leads to a significant reduction in both micro- and macrovascular complications [2–6]. The 10-year follow-up data from the UKPDS taught us that strict glycemic control after initial diagnosis of diabetes continues to reduce late complications and mortality a decade beyond the end of the study (“metabolic memory”) [5]. Three large trials with much more aggressive treatment targets (HbA1c <6% vs. 7-7.9% [7]) than, for example, in the UKPDS (7% vs. 7.9% [2]) showed increased mortality, so an “individualized” target is now favored [1, 2, 7, 8]. This should take greater account of diabetes duration, patient age, comorbidities, and compliance. For the majority of patients (i.e., patients with long life expectancy, short duration of diabetes, lack of serious comorbidities, and good adherence to therapy), an HbA1c <7% is still considered the treatment goal while avoiding hypoglycemia. In the presence of significant comorbidities, especially cardiovascular, short life expectancy, high risk of hypoglycemia, and risk of falls, a relaxation of the HbA1c target to 7-8% should be reconsidered.

Therapy options

The therapy of type 2 diabetes mellitus should have a holistic approach, i.e. weight reduction, optimization of the cardiovascular risk profile and avoidance of hypoglycemia should always be aimed for. Recurrent hypoglycemia, like hyperglycemia, is probably responsible for the long-term complications and should be avoided.

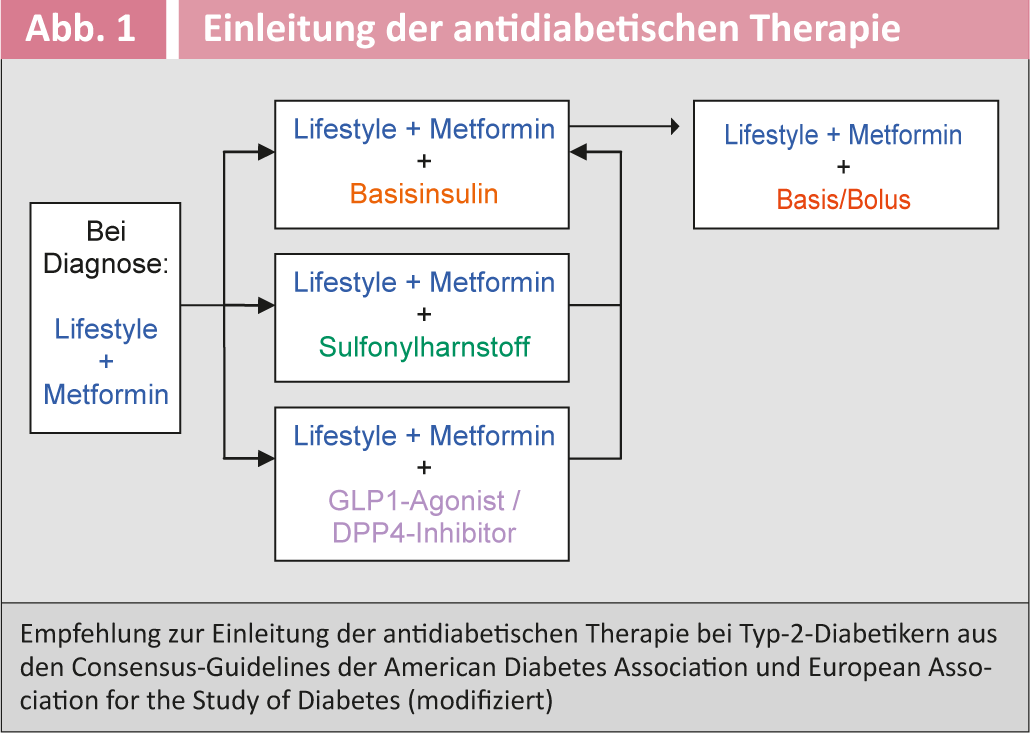

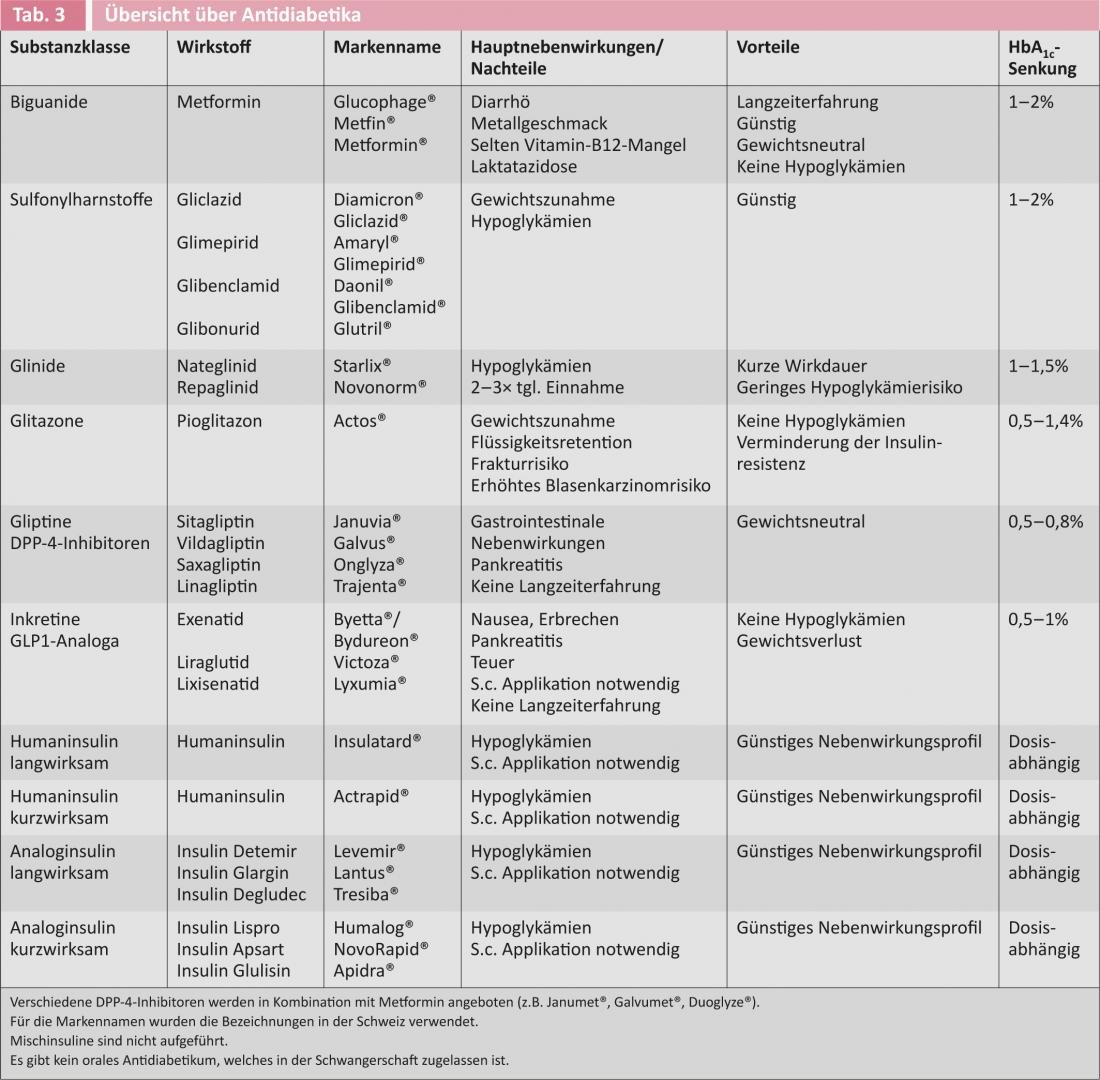

Figure 1 shows the current recommendation for initiation of antidiabetic therapy in type 2 diabetic patients from the American and European diabetes societies [6]. Table 3 provides an overview of the available antidiabetic drugs.

Lifestyle intervention, sports

Lack of exercise and overeating, which consecutively lead to obesity and insulin resistance, are the main environmental factors that increase the risk of diabetes. Even a moderate weight loss of 5-10% of body weight leads to a significant improvement in diabetic metabolic status and cardiovascular risk profile and may make drug therapy for diabetes unnecessary. Lifestyle modifications include a lifelong healthy, balanced, and calorie-restricted diet and regular physical activity (e.g., at least 150 min/week) [8]. Guided nutrition and sports interventions often have lasting effects (e.g. Diafit.ch).

Metformin

Provided there are no contraindications, metformin is the oral antidiabetic of first choice due to its favorable efficacy profile and many years of experience. Metformin is weight-neutral to slightly weight-lowering and does not cause hypoglycemia. Its main effects are reduction of hepatic gluconeogenesis, improvement of glucose uptake into muscle and fat cells, and reduction of triglycerides [9]. Recently, its use has been recommended in patients with little prospect of drastic lifestyle changes at diagnosis. Recent studies postulate reduced cancer incidence and mortality with therapy with metformin. The main side effects are gastrointestinal discomfort, which can be reduced by slowly tapering the drug and providing good information to the patient [9]. In extremely rare cases (<1 case/100 000 patients), the occurrence of lactic acidosis has been described in patients with severe renal insufficiency, so metformin is contraindicated in patients with creatinine clearance <30 ml/min.

Sulfonylureas

Sulfonylureas (glibenclamide, gliclazide, glimepiride, glibonuride) stimulate insulin secretion independently of food intake, thus increasing the risk of hypoglycemia and often leading to weight gain. Hypoglycemia occurs primarily in the elderly and in the presence of severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance <30 ml/min), with the risk being highest with the glibenclamides. The advantage of sulfonylureas is that they have been established for many years and their side effects are therefore well known. Patients on sulfonylurea therapy should be able to measure blood glucose and be educated about hypoglycemia and behavioral measures before driving [1, 6].

Glinide

Like the sulfonylureas, the glinides (nateglinide/repaglinide) stimulate insulin secretion, so combining these preparations is not useful. Glinides have a shorter half-life and are administered with each meal. The measure of weight gain is similar to sulfonylureas, and the risk of hypoglycemia is lower [1, 6].

Glitazones

Glitazones are also called “insulin sensitizers” because they improve the insulin sensitivity of muscle, fat, and the liver. Rosiglitazone was withdrawn from the market in Switzerland in 2010 due to increased cardiovascular risk, leaving pioglitazone as the only approved substance in Switzerland. In addition to the known weight gain, therapy with glitazones can lead to fluid retention, peripheral edema and consecutive heart failure, as well as a decrease in bone density, an increased risk of fractures, and an increased incidence of bladder carcinoma [1, 6]. The Swiss Society of Endocrinology and Diabetology recommends the use of pioglitazone only in selected patients with severe insulin resistance and no contraindications, especially heart failure.

Incretins

GLP1 receptor agonists: The so-called incretin effect describes the phenomenon that oral glucose intake induces a greater insulin release than intravenous glucose administration. The incretin effect is responsible for approximately 60% of postprandial insulin secretion. The two known incretins glucagon-like-peptide-1 (GLP1) and glucose-dependent-insulinotropic-peptide (GIP) are released from enteroendocrine cells of the intestinal wall after peroral food intake. These activate pancreatic β-cells, leading to increased insulin secretion. Furthermore, they inhibit gluconeogenesis via their effect on α-cells, delay gastric emptying, and centrally inhibit appetite. Since the effect of incretins is glucose-dependent, hypoglycemia does not occur with monotherapy. As another positive effect, GLP1 agonists promote weight loss. The GLP1 analogs are expensive and must be applied subcutaneously. The main side effects are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea [1, 6].

Gliptins/DPP-4 inhibitors: GIP and GLP1 are rapidly degraded by dipetidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), so DPP-4 inhibitors have been developed as another class of compounds. Hypoglycemia does not occur during therapy with DDP-4 inhibitors, and they are also weight neutral. The tolerability of DPP-4 inhibitors is good, and gastrointestinal symptoms rarely occur. However, there is evidence of increased pancreatic and pancreatic cancer risk. Long-term studies with hard endpoints and occurrence of side effects are expected soon. In renal insufficiency, dose adjustment is necessary for most DPP-4 inhibitors [1, 6].

Insulin

Insulin deficiency exists in all forms of diabetes, so that insulin replacement is always a suitable therapy option in principle. All patients who are adjusted to insulin therapy should be trained in diabetes counseling regarding blood glucose self-monitoring and behavior during hypoglycemia. In type 2 diabetics, bedtime insulin is started before bedtime at 0.2 E/kgKG or 10 E and slowly titrated up until fasting blood glucose levels are below 7 mmol/l. Basic insulin can be combined with an oral antidiabetic, preferably metformin. Combination with sulfonylureas does not produce a significant additive effect on HbA1c lowering. If HbA1c is still >7%, switch to a base/bolus regimen [1, 6].

Bariatric surgery

The most commonly performed surgery is gastric bypass (called Roux-en-Y) surgery, in which the stomach is substantially reduced in size and the small intestine is connected directly to the stomach. The results of these operations are very convincing in the short term, as in many cases there is a long-awaited weight loss of up to 30-40%. Side effects include signs of malabsorption, especially iron and vitamin B12 deficiency, which must be substituted. Postoperatively, psychological problems often occur, partly due to the loss of the rewarding effect of food. The mortality of gastric bypass surgery is around 0.5%. Whether bariatric surgery is the panacea in the fight against diabetes mellitus cannot be answered to date, as no long-term data regarding diabetes remission and mortality reduction are available. A 2011 International Diabetes Federation (IDF) position paper recommended bariatric surgery primarily for obese type 2 diabetics (BMI ≥35kg/m2) who fail to achieve treatment goals with conventional measures and have cardiovascular comorbidities [10]. Bariatric surgery should be evaluated early as a treatment option in the obese diabetic with insulin resistance, rather than as a “last resort.”

Procedure in everyday clinical practice

When diabetes mellitus is diagnosed, lifestyle interventions and concomitant medication with metformin should be started. Outpatient diabetic education programs are available for lifestyle intervention. In addition, a survey of all cardiovascular risk factors should occur at this time, and end-organ damage must be sought. If diabetes is still insufficiently controlled under these measures (HbA1c >7.0%), metformin should be combined with a sulfonylurea or incretin or, alternatively, with bedtime insulin. If inadequate diabetes control persists, implementation of a bedtime insulin or baseline bolus system is indicated. We recommend that obese diabetics who do not achieve weight loss on their own be referred to an experienced bariatric center. There, participation in an obesity group resp. the option of bariatric intervention be evaluated.

Literature list at the publisher

Stefanie Meyer, MD

CARDIOVASC 2013; 12(4): 20-24