The treatment of urinary tract infections depends on whether the infection is uncomplicated or complicated. Therefore, a careful anamnesis and clarification are indispensable. Uncomplicated cystitis in a woman, provided there are no severe symptoms, can be tentatively approached without antibiotics, as the spontaneous cure rate is 25-40%. Antibiotic therapy must take into account the increasing resistance. Urologic evaluation is recommended for complicated and recurrent UTIs and for all UTIs in men.

Urinary tract infections are common and occur regardless of gender at any age. Three life spans of increased incidence are evident. In infants (m > w), lubrication defects and anatomical malformations not yet recognized are reasons for an increased number of urinary tract infections. The second age peak is found in young, sexually active adults, with females predominating and homosexual males less frequently affected. The third peak occurs in advanced age, when anatomic changes such as mucosal atrophy and cystocele in women and prostatic hyperplasia in men favor urinary tract infections.

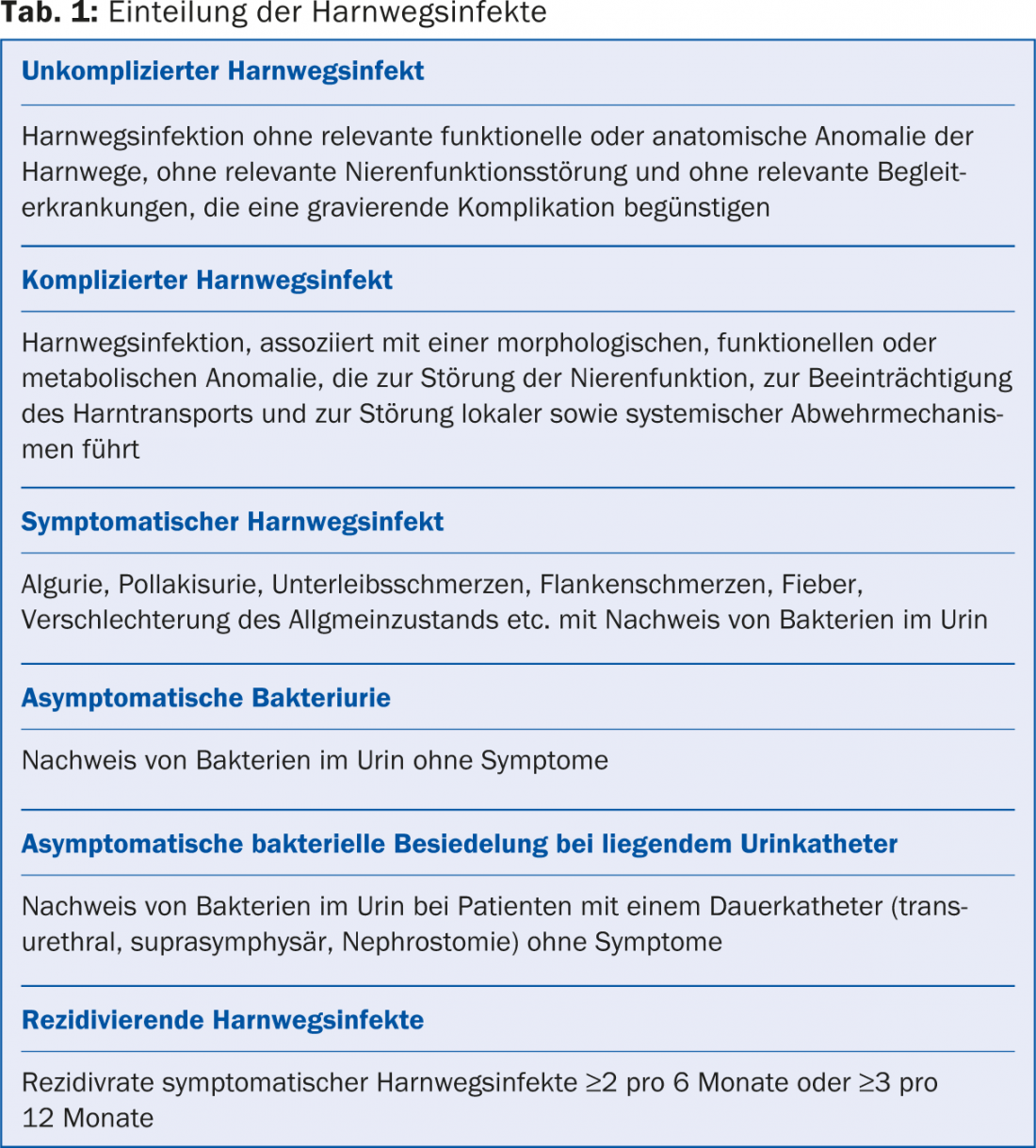

Depending on the patient group, a urinary tract infection confined to the bladder can be treated with antibiotics without further diagnosis or requires further clarification. For this purpose, the terms uncomplicated and complicated urinary tract infections were created (Tab. 1).

Since urinary tract infections are in the vast majority of cases caused by bacteria (viral cystitis caused by adeno-, cytomegaloviruses or polyomaviruses are very rare), the majority of antibiotics used in human medicine are used to treat urogenital infections. Due to increasing resistance, responsible antibiotic use and especially the avoidance of unnecessary therapies are important.

Monitoring and therapy of bacteriuria indicated during pregnancy will not be discussed here.

Uncomplicated cystitis

Young women often suffer from cystitis. These occur at an incidence of 50 UTIs per 100 women per year. Risk factors are sexual intercourse, use of spermicides, previously passed urinary tract infections and a family disposition. Mild symptoms may be treated symptomatically with copious drinking, warm sitz baths, anti-inflammatories, and anticholinergics, as the infection heals spontaneously within seven days in 25-40% of cases [1,2]. Phytotherapy with bearberry leaves (Uvae ursi folium, e.g. Arkocaps

®

Bearberry, Impuls® Bladder and Kidney Dragées, Lapidar 5®, Lapiflu®, Demonatur® Bladder and Kidney Dragées) can be used additionally for a maximum of one week. Bearberry leaves exert their effect through the arbutin they contain, which is converted in the liver and excreted in the urine as a hydroquinone complex. The bacteria present in cystitis cleave the hydroquinone complex and take up the released hydroquinone, which destabilizes their cell membrane, killing them [3]. In case of severe symptoms or persistence of symptoms, antibiotics may be prescribed without further diagnostics (i.e., urine culture, sonography, etc.). The choice of antbiotic will be discussed later.

In postmenopausal women, estrogen deficiency leads to vaginal mucosal atrophy and change in local pH. This leads to the reduction of lactobacilli, whose place is taken by bacteria of the intestinal flora. This close proximity significantly increases the rate of urinary tract infections. In up to 50% of older women, bacteria are found in the urine (bacteriuria), but this does not require treatment in the absence of symptoms and a stable metabolic state [4]. An exception is bacteriuria before traumatic urogenital surgery and during pregnancy, in which case antibiotic therapy is indicated.

Symptomatic cystitis requiring treatment occurs in postmenopausal women with an incidence of seven UTIs per 100 patients per year. If there are no genital changes (descensus, cystocele, etc.) that could cause a residual urine problem, uncomplicated cystitis can also be assumed in this patient group and therapy can be initiated without further diagnostics.

In men, complicated cystitis is present in most cases, which is why a differentiated workup is always indicated in this patient group. This includes a urethritis workup if a diagnosis is suspected, physical and digital-rectal examination, urinalysis incl. Urine culture as well as residual urinary sonography. It is important to detect concomitant inflammation of the adnexa, i.e. prostatitis or epididymitis, since the choice of antibiotic and the duration of antibiotic therapy as well as the accompanying therapeutic measures change depending on the organ involvement. Urologic presentation is often indicated even in acute cases, certainly promptly to rule out organ pathology.

Complicated cystitis

In the absence of healing of uncomplicated cystitis and complicating factors, diagnosis is inevitable. This includes physical examination, particularly urogenital, urinalysis including urine culture, and sonography of the genitourinary system to evaluate residual urine and the upper urinary tract. For the cleanest possible urine collection resp. to avoid contamination with skin and vaginal fora, the following factors should be observed: Men should clean the glans penis with water after retracting the foreskin; women should spread the labia and clean the meatus urethrae with water as well. A medium-jet urine obtained in this way is sufficient for diagnosis in most cases.

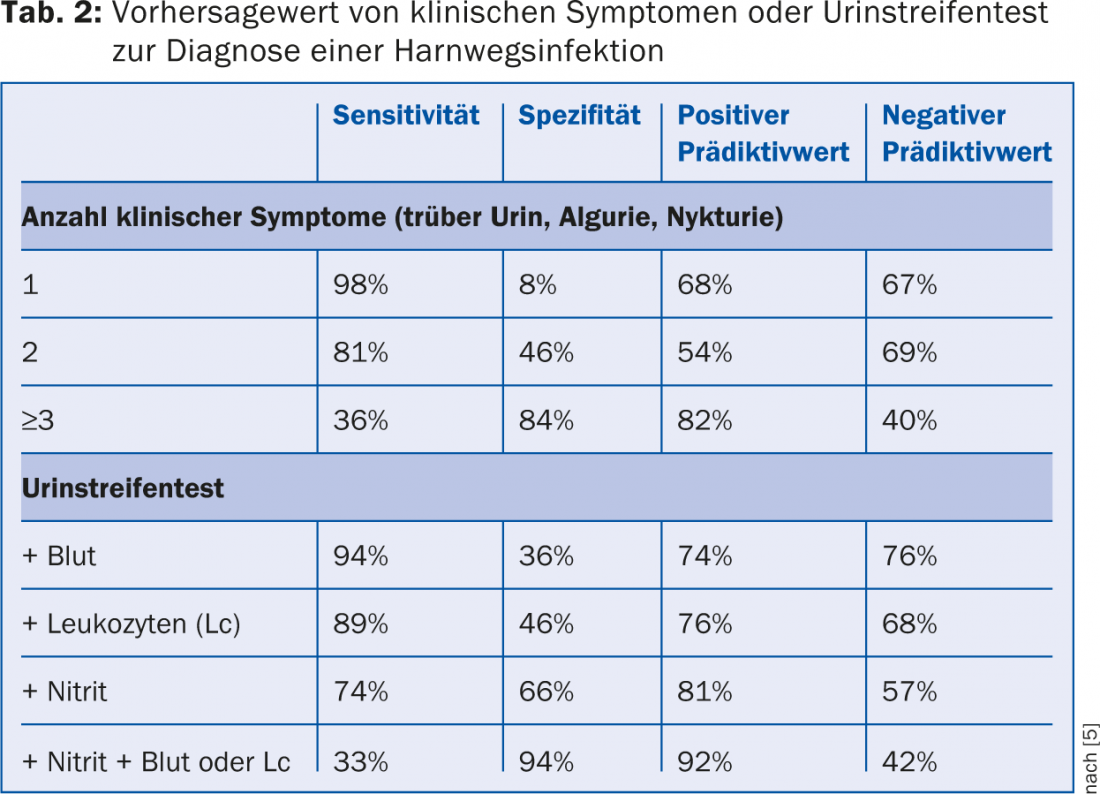

The performance of a urine strip test (e.g. Combur® test) is not sufficient in complicated cystitis [4], as the specificity and sensitivity for diagnosing a urinary tract infection with a urine strip test are insufficient, especially in unclear cases concerning the symptoms (Tab. 2) [5]. Quantitative urine culture with pathogen identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing is an indispensable prerequisite for successful treatment in complicated and recurrent urinary tract infections. Uropathogenic germs (especially E.coli) can cause symptoms even at pathogen counts of 103-104/ml in midstream urine [6], which is why immersion culture media (detection limit >104/ml) are sometimes insufficient. In contrast, the detection of enterococci and group B streptococci in midstream urine is often not reproducible in sterilely collected catheter urine [6], thus should be regarded with caution as a urinary tract infection and rather interpreted as contamination.

In case of abnormalities in the examination, e.g. a renal urinary outflow obstruction, kidney stones, residual urine above 100 ml, space-occupying lesion in the bladder, cystocele or descensus, a urological presentation for further diagnostics including cystoscopy is indicated.

Pyelonephritis

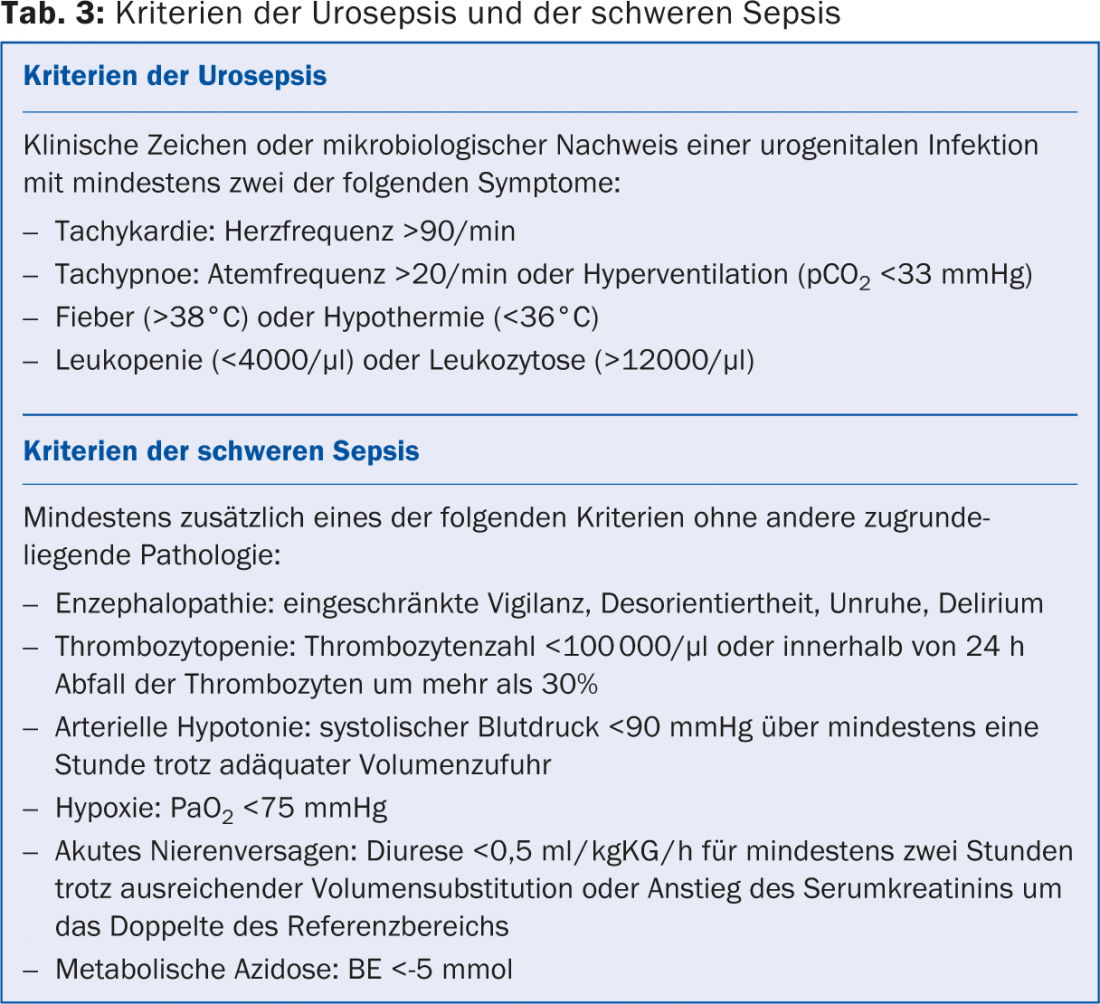

If flank pain, palpable renal lung pain, and/or fever are present in addition to cystitis, pyelonephritis must be assumed. In men, epididymitis or prostatitis must also be ruled out if fever is present. If pyelonephritis is suspected, then urine culture and sonography are indicated in all cases to exclude urinary outflow obstruction and renal abscess of the affected kidney and to exclude residual urine. In case of urosepsis (Tab. 3) or persistent fever under antibiotic therapy, hospitalization for parenteral antibiotic therapy and urine diversion by catheterization is indicated. Likewise, acute epididymitis or prostatitis in men should be clarified by a specialist.

Diagnostics after urogenital surgery and catheterization

Nosocomial urogenital infections are common and have a slightly different spectrum of pathogens than urinary tract infections acquired outside the hospital. Here, Pseudomonas and Serratia are found more frequently, as well as multidrug-resistant germs such as ESBL-bearing E.coli and Klebsiella, which is why taking a urine culture before starting antibiotic treatment is important.

After urogenital surgery and a short time after passive catheterization, a urine strip test is unsuitable for the diagnosis or exclusion of cystitis. Injuries in the urogenital tract (especially after TURP or TURB) lead to leukocyturia and hematuria even in the absence of bacterial infection, rendering the test useless. Also, a positive or negative nitrite detection is not a good indicator for or against an infectious event.

Urinary tract infection in catheter users

Patients with horizontal catheters in the urogenital tract require special attention. A transurethral as well as a suprapubic indwelling catheter (Zystofix) as well as a nephrostomy lead to bacterial colonization of the urinary bladder or the bladder, respectively, even if the highest hygienic standards are observed. of the kidney. The incidence of colonization is 3-10% per day of catheter indwelling [7]. Thus, after 30 days, the urinary tract is bacterially colonized in virtually all patients. Asymptomatic bacterial colonization does not require treatment. There is an exception before a surgical procedure on the urogenital system, here antibiotic therapy is started one day before surgery. In case of complaints such as lower abdominal or flank pain, fever, epididymitis or deterioration of the general condition, it is necessary to take a urine culture from fresh urine (not from the catheter bag) and to ensure continuous urinary diversion (if necessary, change catheter if dysfunction, no supply with a valve).

If the situation permits, targeted antibiotic treatment will be given only after obtaining evidence of the pathogen in the urine culture and resistance testing. If necessary (severe symptoms, fever), calculated antibiotic therapy is given after obtaining the urine culture and is adjusted after obtaining the resistance test. Ideally, the catheter should be changed while on antibiotic therapy appropriate for the sensitivity, as bacteria in the biofilm produced may evade antibiotic therapy. Inserted ureteral catheters (pigtails, double J catheters) do not lead to increased urinary tract infections, but complicate diagnosis and treatment. As with indwelling catheters, the foreign body often causes leukocyturia and erythrocyturia, making urine strip tests useless. Because of the open connection from the bladder to the kidney, cystitis with a ureteral catheter in place is more likely to result in germ ascension and thus pyelonephritis. Here, too, certain bacteria form biofilms, which is why it is necessary to change the ureteral catheter under antibiotic therapy.

Antibiotic therapy and follow-up

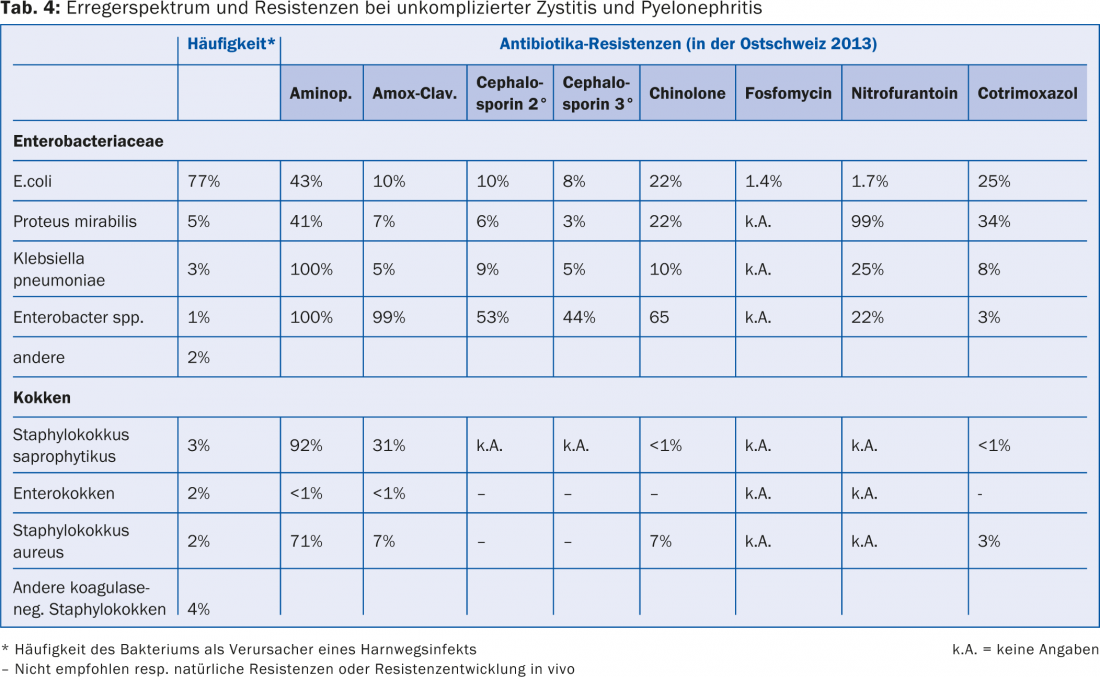

Empiric antibiotic therapy should always be based on the expected spectrum of germs and the resistance situation. Table 4 lists the most common pathogens of community-acquired uncomplicated cystitis and their resistance status for the most important antibiotics in eastern Switzerland in 2013 (according to www.anresis.ch).

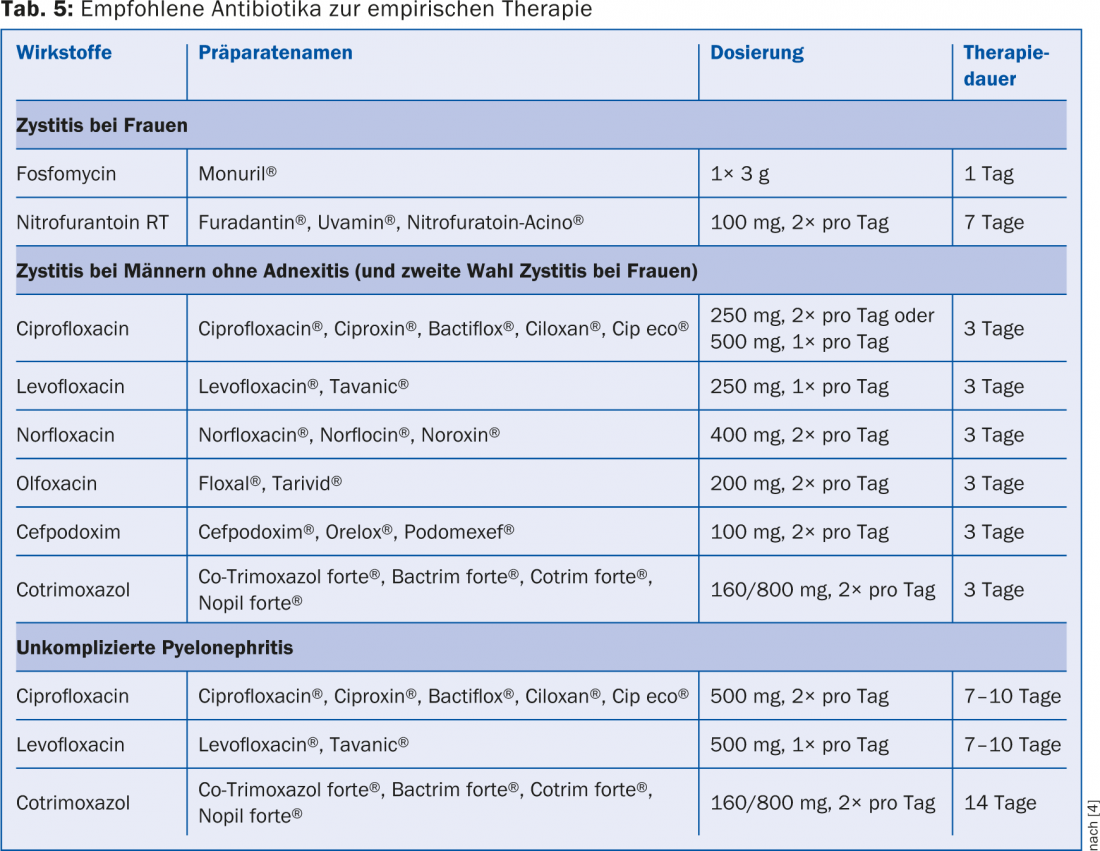

Quinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, ofloxacin, levofloxacin) and cephalosporins (e.g., cefuroxime, cefaclor, cefprozil, cefixime, cefpodoxime) are not recommended as the first choice of therapy because of their effect on physiological intestinal flora and increasing resistance with induction of multidrug-resistant germs. Similarly, resistance to cotrimoxazole is becoming increasingly apparent, which is why nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin have been increasingly used again in recent years for the treatment of cystitis. Because both agents are non-tissue active, they cannot be used in pyelonephritis, prostatitis, or epididymitis. In uncomplicated cystitis without fever, however, a single dose of fosfomycin 3 g or three days of therapy with nitrofurantoin is ideal. The recommended antibiotics for empiric therapy of a urinary tract infection can be seen in Table 5 [4].

Monitoring the success of therapy is only indicated if symptoms persist for 48-72 hours and should then be performed with a urine culture. Persistent leukocyturia and erythrocyturia in the urine strip test a few days after antibiotic therapy are not conclusive of persistence of the UTI.

Prophylaxis

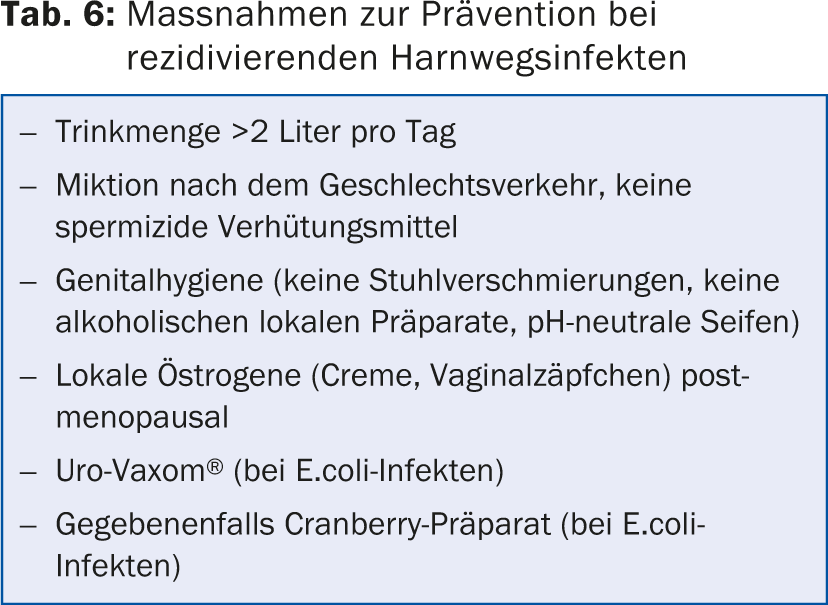

Recurrent cystitis is said to occur when there are three or more symptomatic urinary tract infections per year. The main prophylactic measures for recurrent urinary tract infections in women are summarized in Table 6. Prophylaxis with cranberry is widely used, although studies on efficacy are contradictory. In vitro, decreased bacterial adherence was demonstrated by binding to the pili of E.coli and suppressing pili expression. Proanthocyanidins have been identified as the active ingredient in cranberries, but these are detectable in urine only in minute amounts after consumption of cranberry products. An effect of the proanthocyanidins on the physiological intestinal flora is discussed, whereby this is less “virulent” in the case of colonization of the urinary bladder and does not trigger cystitis [8]. This would mean that only consistent long-term prophylaxis with cranberry products would have an effect, rather than treatment when symptoms occur. However, long-term prophylaxis is often discontinued by patients, not least because of the costs involved.

Uro-Vaxom® is an immunobiotherapy consisting of freeze-dried bacterial lysate of 18 uropathogenic E.coli strains. It stimulates T lymphocytes, induces production of endogenous interferon, and increases urinary secretory IgA levels. Several double-blind studies have demonstrated a reduction in urinary tract infection episodes caused by E.coli [9,10].

In young, sexually active women with recurrent cystitis, the value of cystoscopy and upper urinary tract workup are controversial. However, in older women with recurrent UTIs, cystoscopy is always part of the further urologic workup, as it is in men with a UTI and as in any macrohematuria.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- In uncomplicated cystitis, if symptoms are mild, spontaneous healing can be awaited and only symptomatic therapy can be given, since the infection heals spontaneously within seven days in 25-40% of cases.

- Urologic workup is indicated in complicated and recurrent cystitis. In men, any urogenital infection should be clarified urologically.

- The urine strip test is not always reliable for diagnosing a urinary tract infection. Leukocyturia and hematuria can be detected even without a bacterial infection, especially with a catheter in place in the urogenital system (indwelling catheter, ureteral stent/pigtail) and after surgery on the urogenital system.

- Urinary catheters are virtually always bacterially colonized after 30 days (3-10% colonization rate per day). Without symptoms, there is no indication for examination, urine culture collection or therapy.

Literature:

- Christiaens TC, et al: Randomised controlled trial of nitrofurantoin versus placebo in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection in adult women. Br J Gen Pract 2002; 52(482): 729-734.

- Ferry SA, et al: The natural course of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection in women illustrated by a randomized placebo controlled study. Scand J Infect Dis 2004; 36(4): 296-301.

- Siegers C, et al: Bacterial deconjugation of arbutin by Escherichia coli. Phytomedicine 2003; Suppl 4:58-60.

- Wagenlehner FME, et al: Epidemiology, diagnosis, therapy and management of uncomplicated bacterial community-acquired urinary tract infections in adult patients. 2010. S3 Guideline AWMF Register No. 043/044 Urinary Tract Infections.

- Little P, et al: Dipsticks and diagnostic algorithms in urinary tract infection: development and validation, randomised trial, economic analysis, observational cohort and qualitative study. Health Technol Assess 2009; 13(19): iii-iv, ix-xi, 1-73.

- Hooton TM, et al: Voided midstream urine culture and acute cystitis in premenopausal women. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(20): 1883-1891.

- Warren JW: Catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1997; 11(3): 609-622.

- Hisano M, et al: Cranberries and lower urinary tract infection prevention. Clinics 2012; 67(6): 661-667.

- Bauer HW, et al: Prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections with immuno-active E. coli fractions: a meta-analysis of five placebo-controlled double-blind studies. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2002; 19(6): 451-456.

- Bauer HW, et al: A long-term multicenter, double-blind study of an Escherichia coli extract (OM-89) in female patients with recurrent urinary tract infections. Eur Urol 2005; 47(4): 542-548, discussion 548.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(10): 15-20