Age is not a contraindication to urological surgery. In frail elderly patients, joint management between urologists, anesthesiologists, and geriatricians is recommended. In patients with renal cell carcinoma who are not operable, either controlled waiting or, if symptoms (pain, bleeding) are present, the tumor can be embolized or treated by radiofrequency ablation. In benign prostatic hyperplasia, bipolar TUR-P or laser vaporization can be performed under spinal anesthesia even in the very elderly. In clinically localized prostate carcinoma (T1-2 N0 M0, PSA <50 ng/ml), neither radical prostatectomy nor androgen deprivation therapy should be performed in patients older than 75 years. In muscle-invasive carcinoma of the urinary bladder, radical cystectomy should be attempted even in elderly patients after comprehensive geriatric evaluation.

In recent years, surgical procedures in persons of advanced age have increased significantly. In Germany, between 2007 and 2012, the incidence of surgery increased by an average of 18% in persons older than 70 years, 38% in persons between 85 and 89 years, and 54% from the age of 90 [1]. Especially in urology, predominantly older patients are treated. Among surgical or invasive specialists caring for people over 65, urologists (46% of patients are over 65) follow ophthalmologists (56%) and cardiologists (54%) in 3rd place. 40% of all persons undergoing surgery on the kidneys, ureters, or bladder are over 65 years of age, and the figure is as high as 65% for persons undergoing surgery on the prostate or perivaginal structures [2]. Knowledge of the biology and functionality of elderly urologic patients is useful from a geriatric perspective in the context of preoperative assessment and perioperative management of very elderly patients.

The view of the geriatrician

What makes geriatric patients?

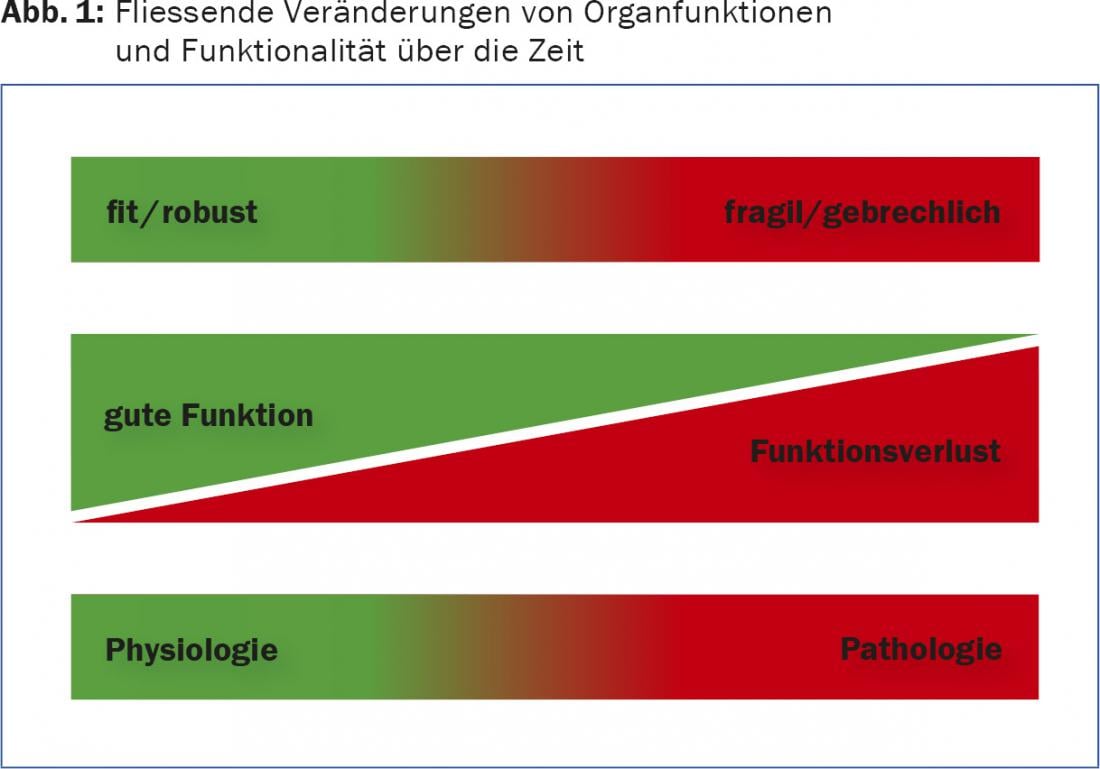

Aging, regardless of existing comorbidities, is associated with a variety of biological changes that may directly and indirectly influence surgical intervention. The elderly suffer losses in sensory perception, mobility and organ function. Robust individuals become frail, they lose functional reserve, and the boundaries between physiological and pathological organ function become blurred (Fig. 1). As a result of altered biology, old people often lose functional organ reserve, which inevitably leads to a disturbance of overall homeostasis (increased vulnerability). If an old body is exposed to an (operative) stressor, it takes much longer for all repair processes to be completed.

In parallel, elderly people are nonspecific and oligosymptomatic in the presentation of their complaints. For example, it is not uncommon for delirium to be the only leading symptom in an elderly man with prostatic hypertrophy and retention bladder. In addition to the “biological burden,” the elderly very often suffer from chronic internal diseases that entail appropriate pharmacotherapy. Polymorbidity and polypharmacy complicate preoperative management and require a great deal of tact and experience. Finally, quite a few elderly people suffer from cognitive impairments or mental illnesses such as depression or anxiety disorders. Elderly persons are sometimes socially isolated and malnourished or undernourished. As a result, treatment should take into account not only the somatic dimension but also social or psychological aspects.

What is the role of geriatric assessment?

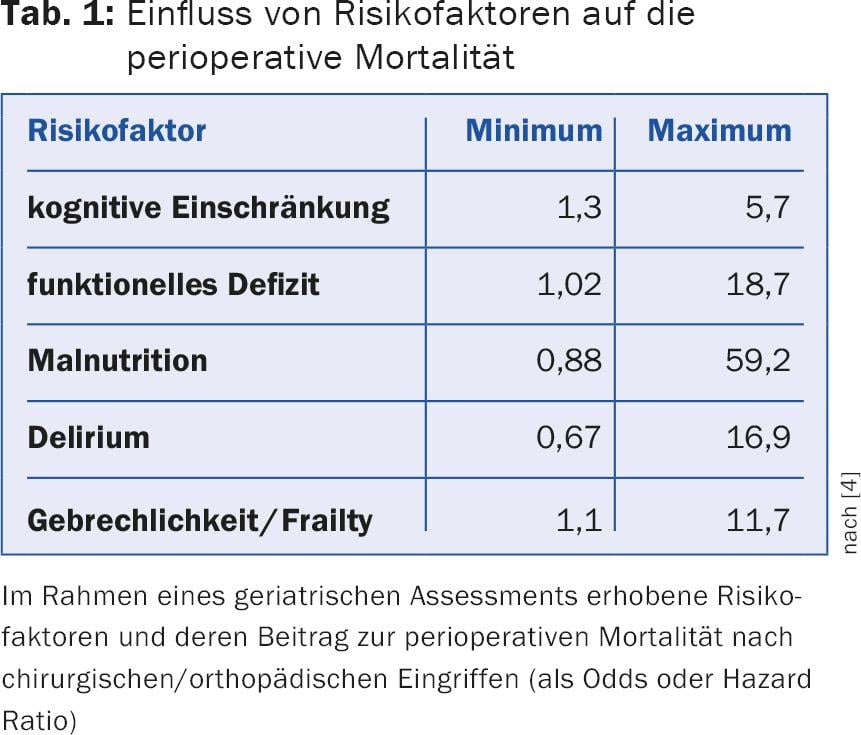

Geriatric assessment is a structured, multidimensional assessment mechanism aimed at identifying reversible risk factors that could have a negative impact on postoperative outcomes prior to surgical intervention. Assessment items relevant to urologic surgery include cognition (judgment regarding preintervention education, risk of delirium), nutrition (wound healing), mobility (early mobilization, risk of falls, wound healing), and medication (risk of delirium due to withdrawal, communication with anesthesia). A variety of validated assessment instruments serve for the assessment, which can be used individually or in combination. Virtually all assessment instruments provide scale values that allow older patients to be classified into risk groups. Table 1 lists the influence of individual problems identified in the geriatric assessment and their impact on postoperative mortality.

The difficulty of the assessment lies in its interpretation. On the one hand, a normal score does not exclude that there is a problem after all (cognition), on the other hand, scores from different instruments cannot simply be added up to a sum score. Therefore, the interpretation of the results in the clinical context and at the individual level is crucial. Simply put, anyone who can add up individual geriatric scores is far from a geriatrician. Of course, internally/geriatrically weighted medical history and a detailed status are part of the assessment. The assessment ideally leads to a multidimensional geriatric intervention. Such programs reduce length of stay and hospital costs in acute hospitals, for example, through positive effects on delirium prevalence, and have a positive impact on hospital mortality [3]. Geriatric interventions are particularly useful before elective procedures because they can reduce perioperative morbidity and risk.

Consequences for urology

Age per se is not a contraindication to urologic or other surgical procedures. In the assessment prior to urologic surgery, elderly patients should be roughly divided into fit, intermediate and frail, primarily on the basis of a clinical assessment. The treating family physicians can make an important contribution here, since they have known their patients for years. Fit elderly persons and those with good cognitive function do not need any further clarification and one does not necessarily have to expect an increased perioperative risk.

For individuals who are considered intermediate or frail, a geriatric assessment is appropriate before elective surgery. Depending on the results, the treating team receives important additional information that is incorporated into perioperative management. This may well involve postponing elective interventions in individuals with marked malnutrition and poor function until the baseline has improved. Geriatric assessments can be well integrated into a preoperative anesthesia consultation.

In the postoperative period, urologists and geriatricians should work closely together, especially in frail patients. In addition to medical expertise, geriatric-trained nursing is needed, especially in the wards of surgical disciplines, who know and can implement the principles of delirium screening and who are prepared to mobilize early postoperatively. With interprofessional concepts that include geriatrics, even very elderly urologic patients will survive their procedure with few complications.

The view of the urologist

In the following, four very common urological clinical pictures and symptoms are described. Interventions in the elderly (75-84 years) and very elderly (85 years and over) patient addressed.

Kidney tumors

The main age of onset for renal cell carcinoma is between the ages of 60 and 70. The classic triad of flank pain, macrohematuria, and palpable flank tumor has become very rare nowadays and is associated with advanced stage and poor prognosis. Due to the widespread use of imaging techniques (sonography, CT, MRI), most renal cell carcinomas are diagnosed at an early stage as an incidental finding during a routine examination.

The standard therapy for renal cell carcinoma is complete surgical removal of the tumor tissue. Depending on the location and size of the tumor, a nephron-sparing technique, i.e., partial nephrectomy, should be attempted in any case. In most cases, this surgery is performed retroperitoneally via a flank incision. Robot-assisted laparoscopic partial kidney resection may also be considered for specific indications, although the ischemia time is longer.

In elderly patients with high comorbidity who are not candidates for surgery, three basic options are available:

- Small renal masses can be monitored periodically by imaging (active surveillance); serial imaging has shown that the growth rate of such masses is low (on average 0.25 cm per year) and the rate of progression to metastatic renal cell carcinoma is low (2-5%).

- Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation in patients with small space-occupying lesions, although this procedure has not yet been definitively established.

- In patients with macrohematuria or flank pain, the tumor can be embolized by the interventional radiologist under local anesthesia. The intention here is purely palliative.

Diseases of the prostate

The standard instrumental treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) remains transurethral resection of the prostate (TUR-P). This operation is preferably performed under spinal anesthesia and is also used in the very elderly. In classical electroresection with monopolar current and corresponding electrolyte-free irrigation solution, a so-called TUR syndrome may rarely occur, i.e., wash-in of the irrigation fluid and hypotonic hyperhydration with hyponatremia and circulatory stress up to pulmonary edema. Alternatively, bipolar resection in saline irrigation can be performed or various laser procedures, which also have the advantage of less bleeding tendency. A completely new procedure, which is being evaluated in Switzerland only in St. Gallen and only within the framework of a prospective randomized study, is embolization of the arteries supplying the prostate [5]. In the very elderly with cognitive impairment or severe PD, surgery should be avoided or incontinence may result.

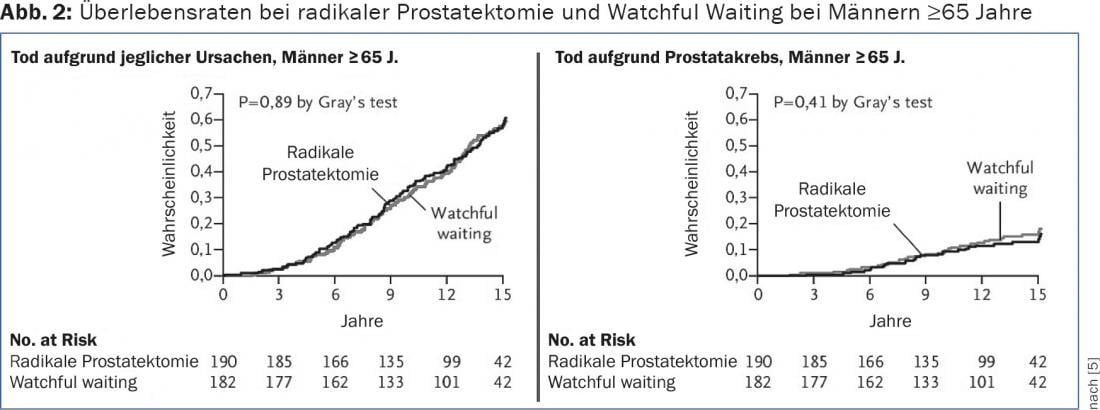

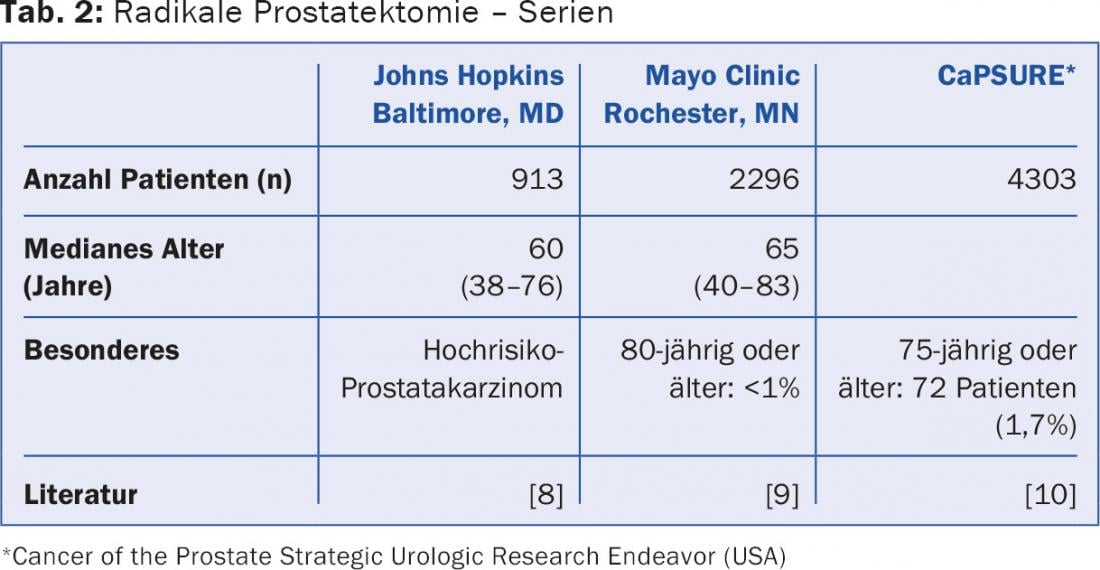

For clinically localized prostate cancer (T1-2 N0 M0), three accepted curative therapies exist: radical prostatectomy (open retropubic or laparoscopic robot-assisted), percutaneous radiotherapy, and LDR brachytherapy (seed implantation). To indicate one of these interventions, most guidelines require a life expectancy of at least ten years independent of the carcinoma. In fact, the only prospective randomized trial “Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting” has shown that only patients younger than 65 years benefit from this surgery (Fig. 2) . However, this is a posthoc subgroup analysis, and selection bias cannot be completely excluded [6]. In addition, mean life expectancy has increased by about five years since the data were collected, and surgery can also prevent local complications. Overall, however, it can be said that curative therapy should not be performed in those calendared over 75 years of age. This is also shown by data from clinical practice in the USA (Tab. 2).

Consistently, in the over 75-year-old patients with clinically localized prostate carcinoma and not highly elevated PSA (>50 ng/ml), one should not fall into therapeutic activism and do “a little something” (high-intensity focused ultrasound, irreversible electroporation). Androgen deprivation therapy also does not prolong survival in this situation, but has serious side effects (cardiac events, decreased glucose tolerance, osteoporosis, cognitive impairment) and is associated with a significantly increased risk of falls.

Urinary bladder cancer

Biologically much more aggressive than localized prostate carcinoma is muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder, which, if untreated, usually leads to death within two years. For this reason, whenever possible, the standard treatment should be sought, i.e., radical cystectomy with urinary diversion via an ileum conduit, even in the very elderly. This can also avoid significant local problems (pain, bladder tamponades). A prerequisite for avoiding perioperative complications is a comprehensive geriatric assessment in advance. Is the anesthesiological resp. If the surgical risk for such a major intervention is nevertheless too high and macrohematuria exists, either an aluminum solution can be instilled into the bladder or the feeding arteries can be embolized [7].

Literature:

- Gosch M, Heppner HJ: The perioperative management of the geriatric patient A challenge, today and in the future. Z Gerontol Geriat 2014; 47: 88-89.

- Drach GW, Griebling TL: Geriatric Urology. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51: S355-S358.

- Flood KL, et al: Effects of an acute care for elders unit on costs and 30-day readmissions. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 981-987.

- Oresanya LB, Lyons WL, Finlayson E: Preoperative Assessment of the Older Patient. A Narrative Review. JAMA 2014; 311: 2110-2120.

- Abt D, et al: Prostatic artery embolization versus conventional TUR-P in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: protocol for a prospective randomized non-inferiority trial. BMC Urol 2014: 14: 94.

- Bill-Axelson A, et al: Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1708-1717.

- Abt D, et al: Therapeutic options for intractable hematuria in advanced bladder cancer. Int J Urol 2013; 20: 651-660.

- Pierorazio PM, et al: Contemporaneous comparison of open vs minimally-invasive radical prostatectomy for high-risk prostate cancer. BJU Int 2013; 112(6): 751-757.

- Tollefson MK, et al: The effect of Gleason score on the predictive value of prostate-specific antigen doubling time. BJU Int 2010; 105(10): 1381-1385.

- Kawakami J, et al: Changing patterns of pelvic lymphadenectomy for prostate cancer: results from CaPSURE. J Urol 2006; 176 (4 Pt 1): 1382-1386.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(1): 34-37