Checkpoint inhibitors have now become established as a new therapeutic standard in the second-line treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma. However, its use could also be useful in first-line therapy.

The use of checkpoint inhibitors is a major advance in the treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma and represents the new standard of care after failure of platinum-containing chemotherapy. Not yet established and the subject of current therapeutic trials is the use of checkpoint inhibitors in first-line therapy of metastatic urothelial carcinoma, in perioperative therapy of localized muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma, or in patients with superficial non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. Radical cystectomy remains the standard of care for localized, muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder (MIBC), especially in younger patients in good general health without relevant comorbidities. When correctly indicated, trimodal therapy can achieve very good results comparable to radical cystectomy in elderly patients with comorbidities or in patients who desire bladder preservation.

Superficial “high-risk” urothelial carcinomas

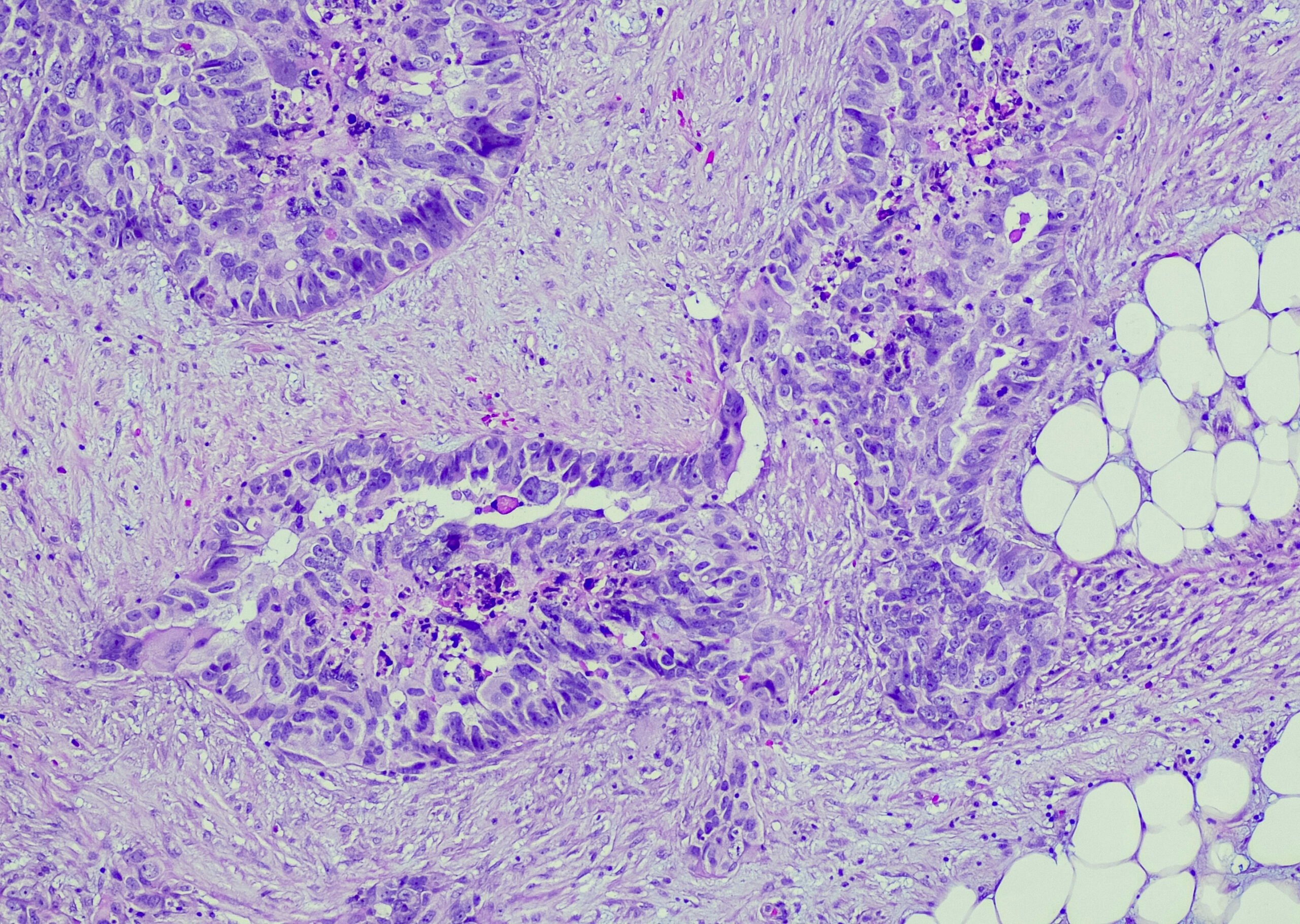

At this year’s ASCO-GU 2019 congress in San Francisco, initial results were presented from the KEYNOTE 057 trial, which is evaluating the use of intravenous administration of pembrolizumab in patients with superficial, noninvasive urothelial carcinoma in a phase II trial in patients who were refractory to intravesical BCG therapy or who relapsed after intravesical BCG therapy [1]. Among the 102 patients with “carcinoma-in-situ” or superficial carcinoma at stage “high-grade” Ta or T1, a complete response was achieved in 41/102 patients (40%), which persisted in 58% of these patients during a median follow-up of 16.7 months. None of the patients suffered progression with muscle-invasive or metastatic disease. These encouraging results are being tested in the prospective randomized phase III KEYNOTE 676 trial (NCT0371032).

Neoadjuvant therapy of localized muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma.

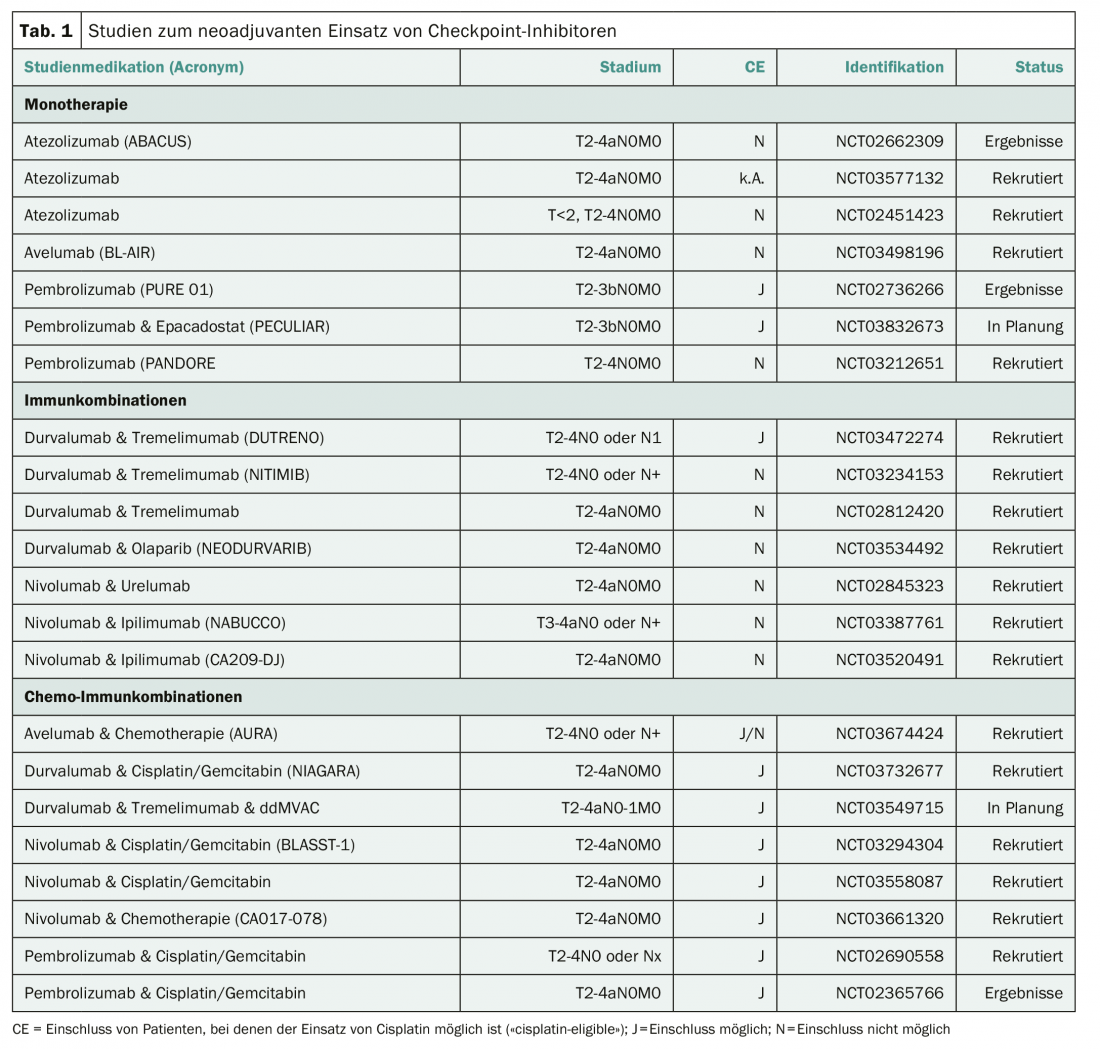

Cisplatin-containing neoadjuvant chemotherapy represents the current standard therapy for patients with localized MIBC. This can result in a survival advantage of approximately 5% over radical cystectomy alone. However, as expected, approximately 45% of patients will relapse despite neoadjuvant chemotherapy. A number of studies are therefore investigating whether the use of checkpoint inhibitors can improve the outcomes of neoadjuvant therapy for localized MIBC (Table 1). An initial phase II study of the use of pembrolizumab has already been published with a rate of 21/52 (42%) pathologically complete remissions and “downstaging” to a pathological stage less than T2 in 27/52 (54%) of patients [2]. Two ongoing neoadjuvant trials in localized MIBC are recruiting in Switzerland. At Inselspital in Bern, a neoadjuvant combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab is currently being investigated in a prospective phase II study in patients for whom the use of cisplatin is not feasible (NCT03234153). The SAKK 06/17 trial is evaluating the neoadjuvant and adjuvant use of durvalumab in combination with four neoadjuvant cycles of cisplatin plus gemcitabine in addition to radical cystectomy (NCT NCT03406650).

Adjuvant therapy of MIBC after radical cystectomy.

The benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy after radical cystectomy of a MIBC is controversial. The largest prospective randomized trial showed no survival benefit over radical cystectomy alone in either nodal-positive or nodal-negative patients [3]. Therefore, there is great motivation to investigate checkpoint inhibitors also in the adjuvant situation after radical cystecomy (Tab. 2) . Results of these studies are not yet available. Two centers in Switzerland (Basel and Zurich) are recruiting into the Checkmate 274 study (NCT02632409).

Alternatives to radical cystectomy

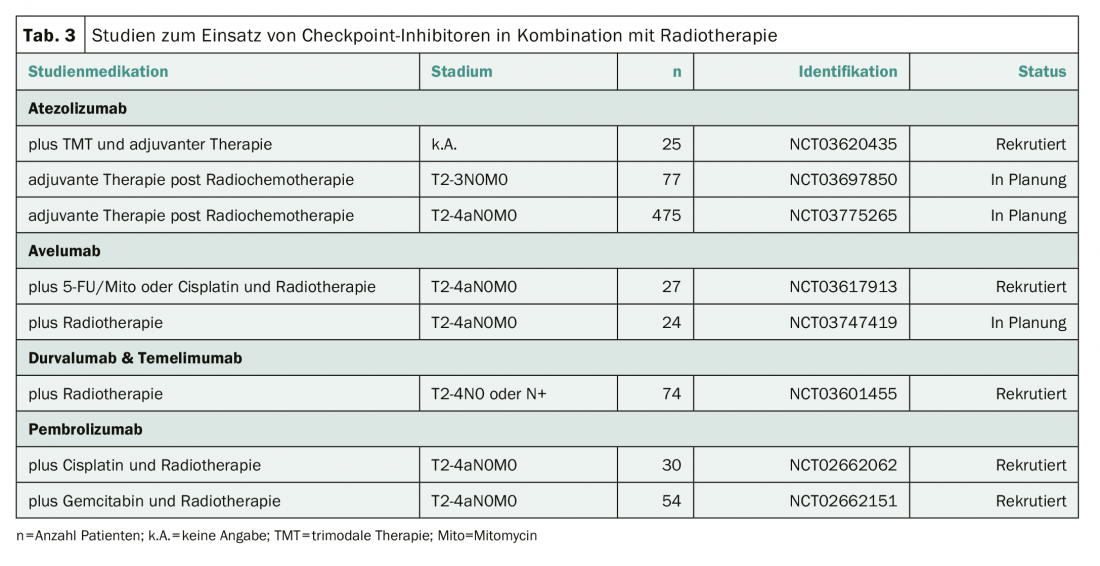

Trimodal therapy represents a valid alternative therapy in patients in whom radical cystectomy cannot be performed or who desire urinary bladder preservation [4]. It is possible that checkpoint inhibitors may also help improve treatment outcomes in this situation. Several studies are therefore investigating the use of checkpoint inhibitors in combination with radiotherapy, or as an extension of trimodal therapy (Tab. 3) . None of these studies is currently recruiting in Switzerland.

First-line therapy of metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

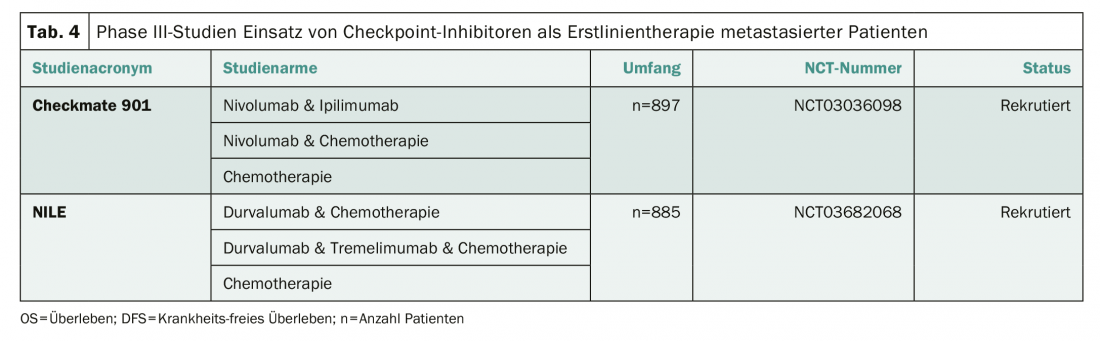

Standard of care for metastatic urothelial carcinoma remains cisplatin-based combination therapy, although the KEYNOTE 361 (NCT02853305) and the IMvigor 130 (NCT02807636) trials suggest the benefit of checkpoint inhibition is likely, particularly in patients with high PD-L1 expression [5,6]. The European Medicines Agency again explicitly points this out in an editorial [7]. Two phase III trials are currently investigating the use of checkpoint inhibitors as an adjunct or alternative to cisplatin-based chemotherapy (Table 4) . Two centers in Switzerland (Baden and Chur) are recruiting into the Checkmate 901 trial (NCT03036098).

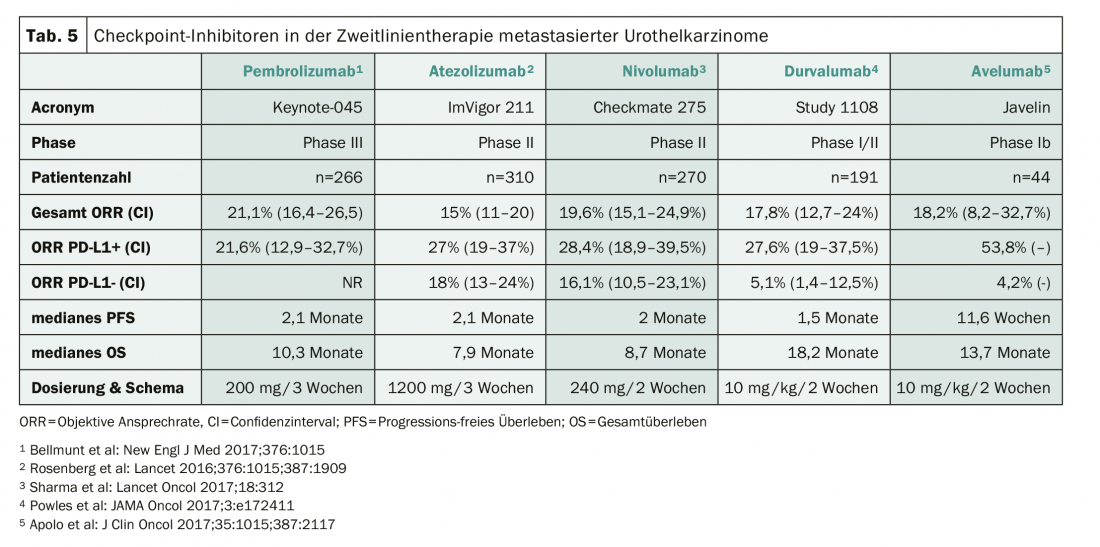

Second-line therapy of metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Checkpoint inhibitors represent the new standard of care in the second-line treatment of urothelial carcinoma after failure of prior platinum-based therapy. Five compounds have been investigated in advanced clinical trials (Table 5). After failure of checkpoint inhibitors, a combination of docetaxel and ramucirumab can be used and lead to temporary tumor control [8].

Literature:

- Balar VA, et al: Keynote 057: Phase II trial of pembrolizumab (pembro) for patients (pts) with high-risk (HR) nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) unresponsive to bacillus calmette-guérin (BCG).J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: (suppl 7S; abstr 350) .

- Necchi A, et al: Pembrolizumab as Neoadjuvant Therapy Before Radical Cystectomy in Patients With Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma (PURE-01): An Open-Label, Single-Arm, Phase II Study. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36:3353-3360.

- Sternberg C, et al: Immediate versus deferred chemotherapy after radicalcystectomy in patients with pT3-pT4 or N+ M0 urothelial carcinoma of the bladder (EORTC 30994): an intergroup, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 76-86.

- James N, et al: Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1477-88.

- Powles T, et al: KEYNOTE-361: Phase 3 trial of pembrolizumab ± chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in advanced urothelial cancer. Eur Urol Suppl 2018; 17 (2): e1147.

- Galsky, et al: IMvigor130: A randomized, phase III study evaluating first-line (1L) atezolizumab (atezo) as monotherapy and in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy (chemo) in patients (pts) with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC). J Clin Oncol 36, 2018 (suppl; abstr TPS4589).

- Gourd E: EMA restricts use of anti-PD-1 drugs for bladder cancer. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19: e341.

- Petrylak DP, et al: Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum-based therapy (RANGE): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 390: 2266-2277.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2019; 7(2-3): 26-29.