Antibiotic resistance is an increasingly important problem with implications for indication and treatment duration. New active substances of the tetracycline class have a favorable side-effect profile and could in the future be alternative options to the current agents.

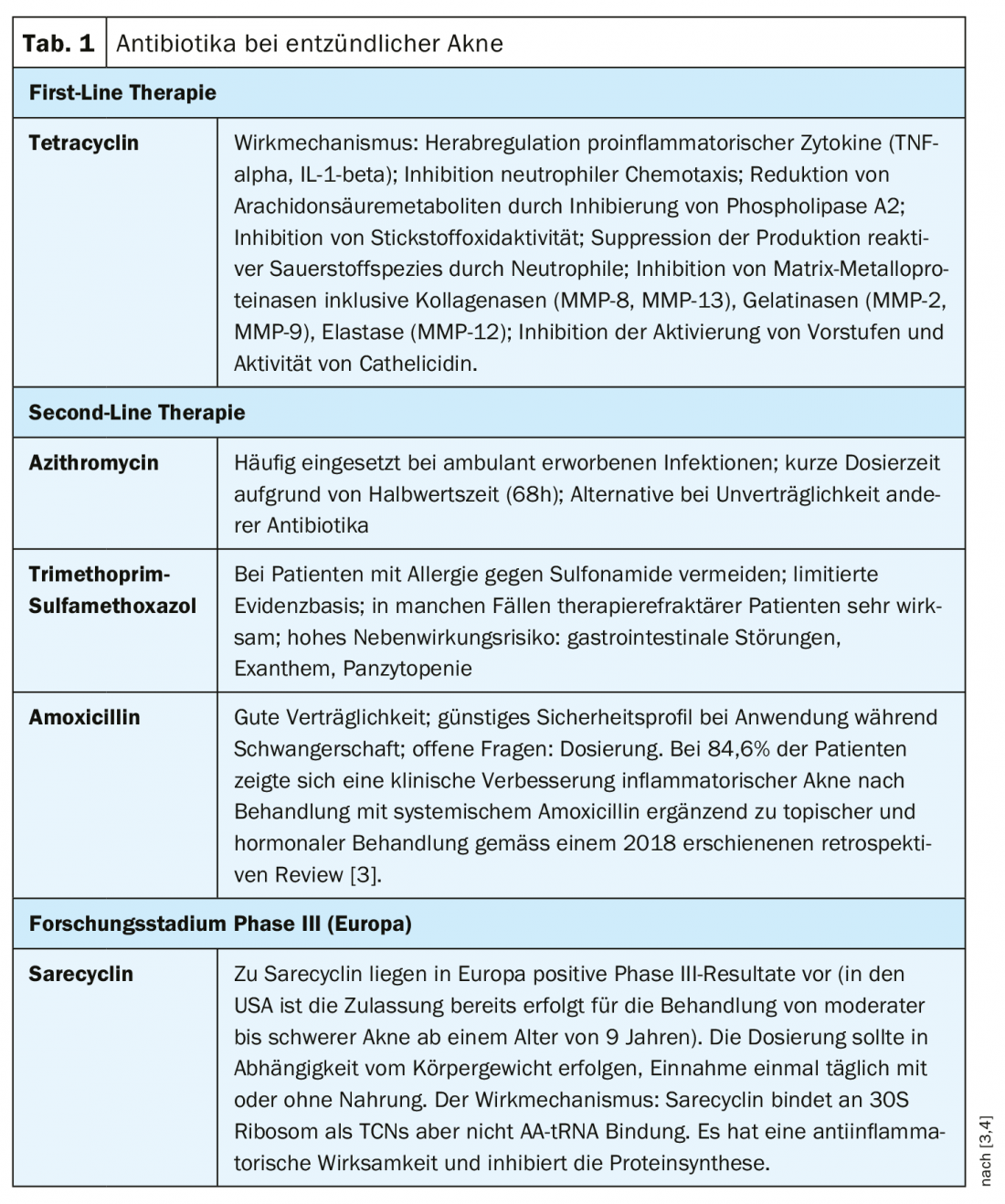

According to a 2018 review, the use of systemic antibiotics is recommended only for moderate to severe forms of acne and in cases where other treatment options are poorly tolerated or contraindicated. Tetracycline is considered a first-line therapy [2] (Table 1). Disadvantages of the current representatives of this antibiotic class are, on the one hand, contraindication in pregnancy and, on the other hand, the risk of side effects. Doxycycline and minocycline are semisynthetic tetracyclines. Compared with doxycycline, minocycline is less likely to cause gastrointestinal side effects and less likely to cause photosensitivity. To reduce the risk of gastrointestinal upset and esophagitis with doxycycline, the following measures have proven effective: Taking with a meal and enough fluids, upright posture several hours after taking, not taking immediately before bed rest [3,4]. Second-line antibiotics mentioned by Neal Bhatia, MD, San Diego include azithromycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Table 1) [4].

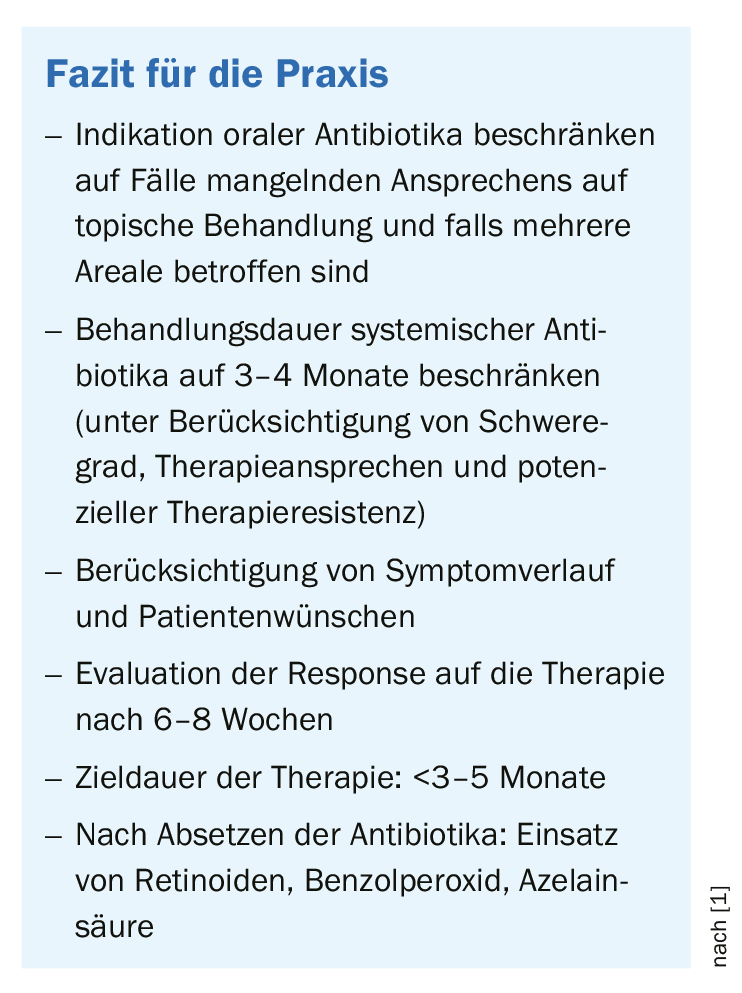

The duration of treatment should be limited to the shortest possible period of time, and concurrent use of retinoids, benzene peroxide, and/or hormonal therapy may be indicated [3,5]. In cases where antibiotic therapy is required over an extended period of time, regular follow-up and evaluation are important. Amoxicillin (Table 1) can be a valuable second-line treatment option and has a favorable safety profile when used during pregnancy [3].

The speaker summarized the most important points regarding the use of antibiotics (Tab. 1) in inflammatory acne diseases as follows [4]:

- Tetracyclines as first-line therapy

- Avoidance of monotherapy; antibiotics should be combined with topical treatment

- Limit use and duration of antibiotics due to antibiotic resistance risk.

Antibiotic resistance debate

Antibiotic resistance can occur as a result of both systemic and topical antibiotic use. Topically applied antibiotics can influence microbial colonization and antibiotic resistance patterns of anatomic regions outside the application site [6]. The conclusion of a 2017 article in the BMJ on the problem of antibiotic resistance is that it is essential to limit the use of antibiotics to cases in which it is really necessary, and the duration of use should be as long as necessary and as short as possible [7]. According to the WHO, numerous findings show that the efficacy of antibiotics is comparable in many cases for short vs. longer periods of use. The WHO evidence-based guidelines include recommendations for the use of antibiotics in dermatologic diseases [8]. In modern medicine, “shared-decision making” is also advocated; education and dialogue with patients for shared decision making is increasingly considered important, including when it comes to the topic of antibiotics and whether discontinuation is appropriate when symptoms subside [9].

Sarecycline as a future therapeutic option?

Side effects limit the use of the current antibiotic representatives from the tetracycline class as therapeutics against acne. Sarecycline (Table 1) is a new “narrow-spectrum” antibiotic in the tetracycline class for moderate to severe forms of acne. A study of the efficacy and safety of this substance came to a positive conclusion. Accordingly, it is a safe, well-tolerated and effective antibiotic for use in moderate to severe forms of acne. The incidence of side effects known for tetracyclines is low.

Results from two phase III studies (Study A: n=968; Study B: n=1034) over a 12-week study period [10]: Patients aged 9-45 years with a moderate to severe form of acne (IGA score ≥3, 20-50 inflammatory, ≤100 non-inflammatory lesions) were randomly assigned to the sarecycline 1.5 mg/kg/day or placebo condition. Outcome parameters were defined as reduction of inflammatory lesions and symptom relief according to IGA (2 degrees of improvement and score 0=lesion-free or 1=almost lesion-free). At 12 weeks after baseline, the two sarecycline conditions showed higher IGA success rates: 21.9% (A) resp. 22,6% (B) vs. 10.5 (A) resp. 15,3% (B) in the placebo conditions (p<0.0001; p<0.005). The reduction in inflammatory lesions was also significantly greater in the treatment arms compared with placebo: -51.8% (A) resp. -49,9% (B) vs. -35.1% (A) resp. -35,4% (B) (p<0.0001; p<0.0001). The most common adverse reactions (≥2% in either the sarecycline condition=S or the placebo condition=P): study A: nausea (S: 4.6%; P: 2.5%), nasopharyngitis (S: 3.1%; P: 1.7%), headache (S: 2.7%; P: 2.7%), vomiting (S: 2.1%; P: 1.4%). Study B: nasopharyngitis (S: 2.5%; P: 2.9%), headache (S: 2.9%; P: 4.9%). Vestibular side effects (dizziness, tinnitus, vertigo) and phototoxicity (sunburn, photosensitivity) occurred in ≤1% of sarecycline patients. The rate of gastrointestinal side effects are low according to the authors. Among female participants, rates of vulvovaginal candidiasis were low (Study A: S: 1.1%; P: 0. Study B: S: 0.3%; P: 0.) Mycotic infections also occurred infrequently (Study A: S: 0.7% vs. P: 0. Study B: S: 1.0% vs. P: 0).

Literature:

- Practical management of acne for clinicians: An international consensus statement from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne February 2018 JAAD, Volume 78, Issue 2, Supplement 1, S1-S23.

- Garner SE, et al: Minocycline for acne vulgaris: efficacy and safety. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Aug 15;(8):CD002086. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002086.pub2.

- Guzman AK, Choi JK, James WD: Safety and effectiveness of amoxicillin in the treatment of inflammatory acne. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018 Jun 8;4(3):174-175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2018.03.006. eCollection 2018 Sep.

- Bhatia N: Slide presentation. Atopic dermatitis comorbidities: what do derms need to know? Neal Bhatia, MD. AAD Annual Meeting 2019, Washington, March 2 2019. www.aad.org/faculty/handout/AM2019/accepted/FRM%20F005%20-%20Bhatia%20-%2015079%2012447.pdf

- Zaenglein AL, et al: Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-973.e33.

- Del Rosso JQ, et al: Status Report from the Scientific Panel on Antibiotic Use in Dermatology of the American Acne and Rosacea Society. Part 1: Antibiotic Prescribing Patterns, Sources of Antibiotic Exposure, Antibiotic Consumption and Emergence of Antibiotic Resistance, Impact of Alterations in Antibiotic Prescribing, and Clinical Sequelae of Antibiotic Use. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016 Apr; 9(4): 18-24. Published online 2016 Apr 1. PMCID: PMC4898580. PMID: 27462384

- Llewelyn MJ, et al: The antibiotic course has had its day. BMJ 2017; 358: j3418. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3418 (Published 26 July 2017).

- WHO: www.who.int/features/qa/stopping-antibiotic-treatment/en/

- CBSNEWS: www.cbsnews.com/news/do-you-really-need-to-take-all-those-antibiotics/

- Moore A, et al: Once-Daily Oral Sarecycline 1.5 mg/kg/day Is Effective for Moderate to Severe Acne Vulgaris: Results from Two Identically Designed, Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trials. J Drugs Dermatol 2018;17(9): 987-996.

- Moore J: Efficacy and Safety of Subantimicrobial Dose, Modified-Release Doxycycline 40 mg vs Doxycycline 100 mg vs Placebo in the Treatment of Severe Acne J Drugs Dermatol 2015; 14(6): 581-586.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2019; 29(3): 35-36 (published 6/14/19, ahead of print).