It is not yet possible to predict which actinic keratoses (AK) will develop into invasive squamous cell carcinoma. It is therefore advisable to treat all AK lesions. If AK is treated early, the chances of recovery are good. Various factors play a role in the success of a topical therapy that can be applied by patients themselves, including compliance.

Actinic keratosis (AK) is a common precancerous skin change in fair-skinned people [1]. AK lesions occur singly or in multiples in areas of skin exposed to light (e.g. face, scalp, back of hands). The cause is cumulative damage to the skin caused by UV radiation [2]. UV radiation induces loss-of-function mutationsof the tumor suppressor gene p53 [3]. Even if most actinic keratoses do not develop into squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), they should be treated, as it is not possible to predict whether and which AK will degenerate and develop into SCC (Box) [4].

| The data on the probability of progression from AK to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is inconsistent. Older data give estimates of 0.025% up to 16% for an individual lesion per year [3]. Transformation rates of 0.15-80% per year were therefore estimated for a patient with 6-8 lesions. The guideline published in 2023 cites a large prospective study with a follow-up of AK over a period of five years [3,24]. In this study, the risk of progression from AK to invasive PEK was 0.60% in year 1 and 2.57% in year 4 after initial diagnosis of AK [24]. |

Ablative procedures, surgical interventions, photodynamic therapy or medication can be used to treat AK. The selection of the most suitable treatment option for the individual patient depends, among other things, on the number and location of the lesions, as well as the patient’s age and state of health.

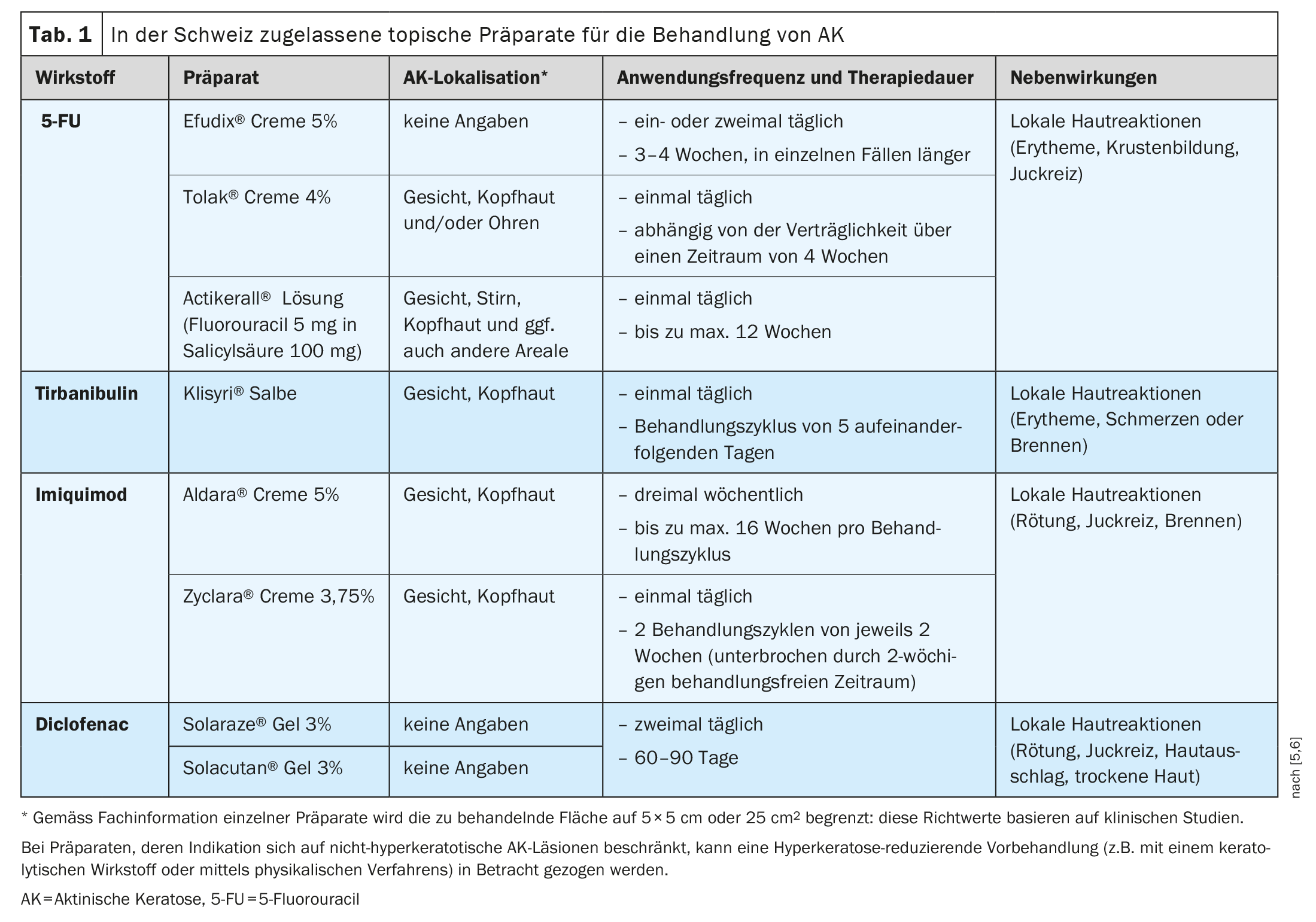

Table 1 shows creams, gels, solutions or ointments authorized by Swissmedic for the treatment of AK (with the exception of substances used in the context of photodynamic therapy) with the localization, frequency of application and duration of treatment specified in the authorization [5,6]. The most common side effects of these treatment options are temporary local skin reactions. Which preparation is most suitable for which patient depends on various patient-, lesion- and therapy-related factors.

5-FU inhibits thymidylate synthase

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) is a pyrimidine analog that belongs to the family of antimetabolites. The mechanism of action is based on the inhibition of thymidylate synthase, an enzyme that is required for DNA synthesis and for the formation and function of RNA [7]. Various formulations of the medication are commercially available, each of which can be applied once or twice daily to the area of the AK lesions for up to a maximum of 12 weeks. 5-FU is used to treat a single lesion or large areas, with complete healing rates after eight weeks ranging from 96% in patients treated with 5% 5-FU to 48% in patients receiving 0.5% 5-FU cream [8,9]. The 4% 5-FU cream is applied once daily over a period of 2-4 weeks and has been shown to be better tolerated than a 5% 5-FU cream applied twice daily [10]. In addition, a combination preparation of a 0.5% 5-FU solution with 10% salicylic acid is now available, which has been shown to be more effective than placebo in the treatment of AK on the face and scalp: the proportion of patients with complete freedom from manifestations was up to 49.5% vs. 18.2% when the preparation was applied once daily for 12 weeks to a total area of no more than 25 cm.2 was applied [11].

Tirbanibulin blocks tubulin polymerization

Tirbanibulin is a proapoptotic agent from the group of tubulin inhibitors for the local treatment of actinic keratoses of the face and scalp. The effects are based on a targeted inhibition of tubulin polymerization, which induces apoptosis [12]. In addition, the intracellular protein tyrosine kinase Src, which is increasingly expressed in AK, is blocked [13]. The preparation is applied once a day for 5 days, to a maximum of 25 cm2 skin area. In the double-blind vehicle-controlled randomized pivotal trials, subjects (n=702) applied either tirbanibulin ointment 1% (10 mg/g) or a vehicle preparation to lesions on the face or scalp for five days. Complete healing on day 57 (primary endpoint) was achieved by 49% of patients treated with tirbanibulin compared to 9% of the vehicle control group in the pooled analysis of the two pivotal clinical trials (p<0.0001). A 75% cure rate was achieved in 72% of patients treated with tirbanibulin compared to 18% with vehicle [14].

Imiquimod is a TLR agonist

Imiquimod acts as a topical immune response modifier. Toll-like receptors (TLR), which are located on the surface of dendritic cells, monocytes, macrophages and Langerhans cells, promote the activation of the innate and adaptive immune response, leading to the release of cytokines and chemokines. Imiquimod also has a direct apoptotic effect on tumor cells [7]. Imiquimod is approved in various concentrations for AK on the face or scalp in immunocompetent adult patients.

The 3.75 percent cream formulation is applied once daily for a two-week cycle, followed by a two-week treatment break and a further two-week treatment cycle [15–17]. Imiquimod 5% cream is applied three times a week up to a maximum of 16 weeks per treatment cycle.

Diclofenac blocks the enzyme cyclooxygenase 2

Treatment with a gel containing diclofenac has also proven to be effective for AK. Diclofenac is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug that blocks the enzyme cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) [20]. A gel consisting of 3% diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronic acid is available for the treatment of AK on the face and scalp. The recommended treatment regimen consists of twice-daily application for 60-90 days and leads to a complete clearance rate of 41% at the end of treatment, which increased to 58% at a follow-up examination 30 days after treatment [20]. In a systematic Cochrane review, diclofenac hyaluronic acid gel was found to have similar efficacy compared to 5-FU and imiquimod 5% in terms of complete clearance [21–23].

Literature:

- “Evidence-based and patient-oriented treatment decisions for actinic keratosis”, https://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/29871/1/Steeb_Theresa.pdf,(last accessed 18.10.2023)

- Gellrich FF, et al: Retrospective analysis of individual sun protection counseling in patients with actinic keratoses. Act Dermatol 2016; 42: 125-130.

- “S3 Guideline Actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin”, Version 2.0, Register number 032 – 022OL.

- “Patient guideline on actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin”, consultation version, as of December 2022. www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de,(last accessed 18.10.2023).

- Drug information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch,(last accessed 18.10.2023)

- Del Regno L, et al: A Review of Existing Therapies for Actinic Keratosis: Current Status and Future Directions. Am J Clin Dermatol 2022; 23(3): 339-352.

- Micali G, et al: Topical pharmacotherapy for skin cancer: part I. Pharmacology. JAAD 2014; 70(965): e1-12.

- Peris K, et al: Italian expert consensus for the management of actinic keratosis in immunocompetent patients. JEADV 2016; 30: 1077-1084.

- Ezzedine K, Painchault C, Brignone M: Use of complete clearance for assessing treatment efficacy for 5-fluorouracil interventions in actinic keratoses: how baseline lesion count can impact this outcome. J Mark Access Health Policy 2020;8: 1829884.

- Dohil MA: Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of 4% 5-fluorouracil cream in a novel patented aqueous cream containing peanut oil once daily compared with 5% 5-fluorouracil cream twice daily: meeting the challenge in the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol 2016; 15: 1218-1224.

- Stockfleth E, et al: Efficacy and safety of 5-fluorouracil 0.5%/salicylic acid 10% in the field-directed treatment of actinic keratosis: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial. Dermatol Ther Heidelb 2017; 7: 81-96.

- Kempers S, et al: Tirbanibulin ointment 1% as a novel treatment for actinic keratosis: phase 1 and 2 results. J Drugs Dermatol 2020; 19(11): 1093-1100.

- Kim, et al: Cancer research and treatment 2017; Antitumor Effect of KX-01 through Inhibiting Src Family Kinases and Mitosis. 49(3): 643-655.

- Blauvelt A, et al: Phase 3 Trials of Tirbanibulin Ointment for Actinic Keratosis NEJM 2021; 384: 512-520.

- Hanke CW, et al: Imiquimod 2.5% and 3.75% for the treatment of actinic keratoses: results of two placebo-controlled studies of daily application to the face and balding scalp for two 3-week cycles. JAAD 2010;62(4): 573-581.

- Swanson N, et al: Imiquimod 2.5% and 3.75% for the treatment of actinic keratoses: results of two placebo-controlled studies of daily application to the face and balding scalp for two 2-week cycles. JAAD 2010; 62(4): 582-590.

- Hanke CW, et al: Complete clearance is sustained for at least 12 months after treatment of actinic keratoses of the face or balding scalp via daily dosing with imiquimod 3.75% or 2.5% cream. J Drugs Dermatol 2011; 10(2): 165-170.

- Bubna AK: Imiquimod – its role in the treatment of cutaneous malignancies. Indian J Pharmacol 2015; 47(4): 354-359.

- Swanson N, et al: Imiquimod 2.5% and 3.75% for the treatment of actinic keratoses: two phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. J Drugs Dermatol 2014; 13: 166-169.

- Nelson C, et al: Phase IV, open-label assessment of the treatment of actinic keratosis with 3.0% diclofenac sodium topical gel (Solaraze) J Drugs Dermatol 2004; 3: 401-407.

- Gupta AK, et al: Interventions for actinic keratoses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD004415.

- Steeb T, et al: A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions for actinic keratosis from post-marketing surveillance trials. J Clin Med 2020; 9: 2253.

- Tan JHY, Hsu AAL: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) exacerbated respiratory disease phenotype: topical NSAID and asthma control – a possible oversight link. Respir Med 2016; 118: 1-3.

- Criscione VD, et al: Actinic keratoses: Natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer 2009; 115: 2523-2530.

- Tan IJ, Pathak GN, Silver FH: Topical Treatments for Basal Cell Carcinoma and Actinic Keratosis in the United States. Cancers (Basel) 2023; 15(15): 3927.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2023; 33(5): 32-34

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2023: 11(5): 38-39

Cover picture: Future FamDoc, wikimedia