The etiology of irritable bowel syndrome is multifactorial. Lifestyle modification is an important component of basic therapy. The choice of therapy method should be made together with the patient. Psychotherapy should be offered for severe courses and psychological comorbidities.

Irritable bowel syndrome presents with a variety of symptoms, with abdominal pain, stool irregularity, and bloating being prominent [1,2]. The symptoms cause a subjectively strongly felt restriction of the quality of life and everyday life of the affected person, without sufficiently explaining somatic (biochemical and/or structural) correlates [3].

Definitions

Nationally and internationally, different definitions may be applied to IBS. Globally, the most commonly used criteria are the Rome IV criteria (2017) [4]. In Germany, the definition is according to the S3 guideline (currently under revision) [1]. According to this guideline, bowel-related complaints, excluding organic diseases, which have persisted for at least three months and reduce the patient’s quality of life are characteristic [1]. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome represents a special form, which is thought to be caused by alterations in the microbiome, gut-brain axis, and immune response [5]. The Rome IV criteria divide into four subtypes (classification using Bristol Stool Form Scale [BSFS]) [4,6]:

- RDS-D (diarrhea)

- >25% of stools liquid or contain soft lumps (type 6 and 7)

- RDS-C (constipation)

- >25% of stools solid globules or sausage-like, lumpy (types 1 and 2)

- RDS-M (mixed)

- >25% of chairs type 1 and 2; >25% type 6 and 7

- RDS-U (unsubtyped)

- Not classifiable on the basis of the BSFS

Comorbidities: Concomitant diseases play an important role in the context of IBS. A meta-analysis showed that up to 94% of all patients with IBS suffer from psychological comorbidities, which have an impact on the course of the disease and the severity of symptoms [7]. Anxiety disorders and depression are two psychological comorbidities that are often associated with IBS and in turn also significantly increase the risk for IBS genesis [8,9].

Epidemiological aspects: Recent studies show an increasingly high prevalence of IBS (11.2% worldwide). It should be noted that this figure exceeds the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease in total [3,10]. Women are more likely than men to be affected by the disease (2:1) [11]. Given the high prevalence, the magnitude of the socioeconomic costs incurred can also be surmised. Thus, only direct costs average EUR 572 per patient per year [12].

Pathophysiology

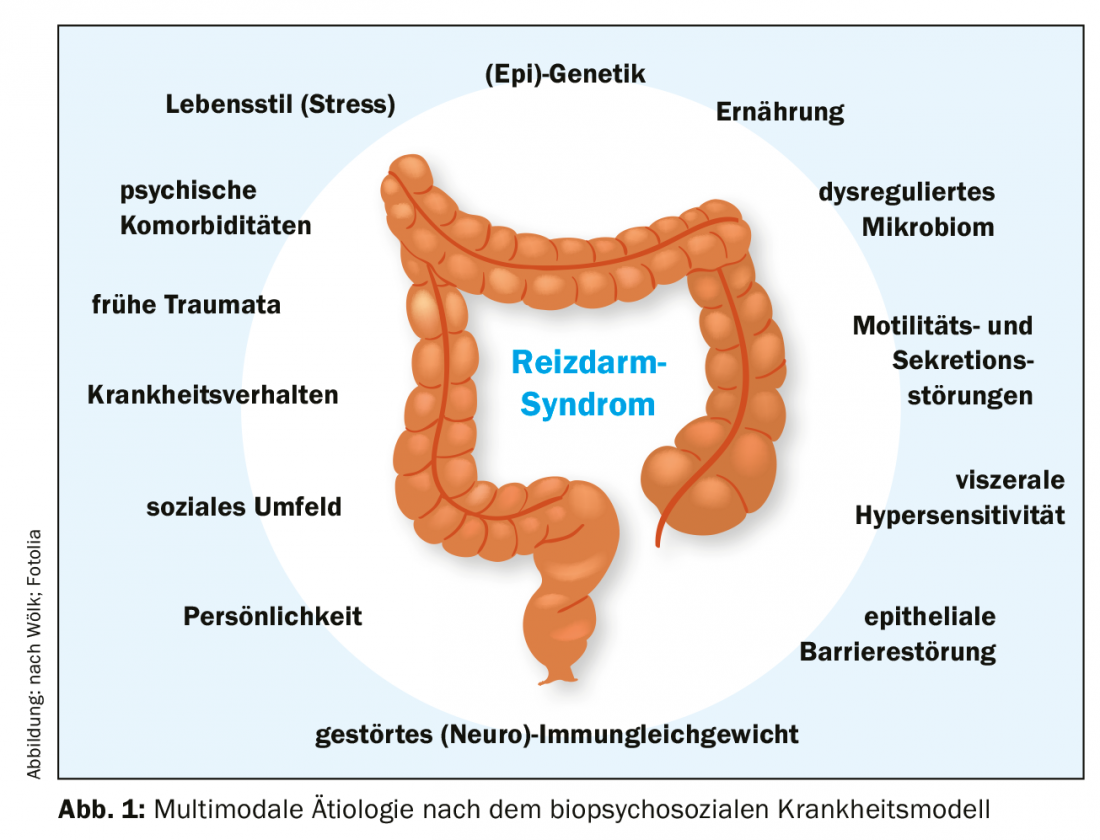

The etiological factors influencing IBS are not yet fully researched and understood. What is certain, however, is the multifactorial genesis, with the biopsychosocial model of disease offering the best explanatory approach [13]. According to this, somatic, psychological and social factors intertwine and in combination cause irritable bowel syndrome (Fig. 1).

Biological aspects: The somatic influencing factors are currently a strong focus of research. The microbiome should also be mentioned here as a possible therapeutically significant starting point [14,15]. An altered composition of the intestinal flora can be detected in patients compared to healthy control subjects [14], although the data on this is not uniform to date. Likewise, the microbiome seems to influence the gut-brain axis dysfunctional in IBS (microbiome-gut-brain axis) and would be an explanation for the post-infectious form of IBS as well as for the increased risk after antibiotic use [3,5,16].

Other biological changes include increased visceral sensitivity [17] and increased permeability of the gastrointestinal epithelial barrier [18], often associated with alterations in (neuro)immune balance with increases in endocrine/paracrine active cells in the mucosa [19]. Last but not least, genetic aspects should be mentioned [3].

Furthermore, motility and secretion of the colon are altered and thus a therapeutic approach [20]. In these changes, the gut-brain axis plays an important role and most likely also contributes to the association with mental illness [21].

Psychosocial aspect: Psychological comorbidities contribute to the development of IBS and increase the risk of severe and refractory disease [7]. Conversely, IBS is also a risk factor for anxiety disorders, depression, and other somatoform disorders [8,9]. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) plays an important role in this context [22,23]. Chronic stimulation (e.g., prolonged stress) triggers inflammatory signaling cascades in the gastrointestinal tract, which may contribute to the maintenance and/or exacerbation of symptoms. Learned illness behaviors, socioeconomic status, and early childhood traumatic experiences are other important aspects that may contribute to the development and persistence of IBS [10,24,25].

Diagnostics

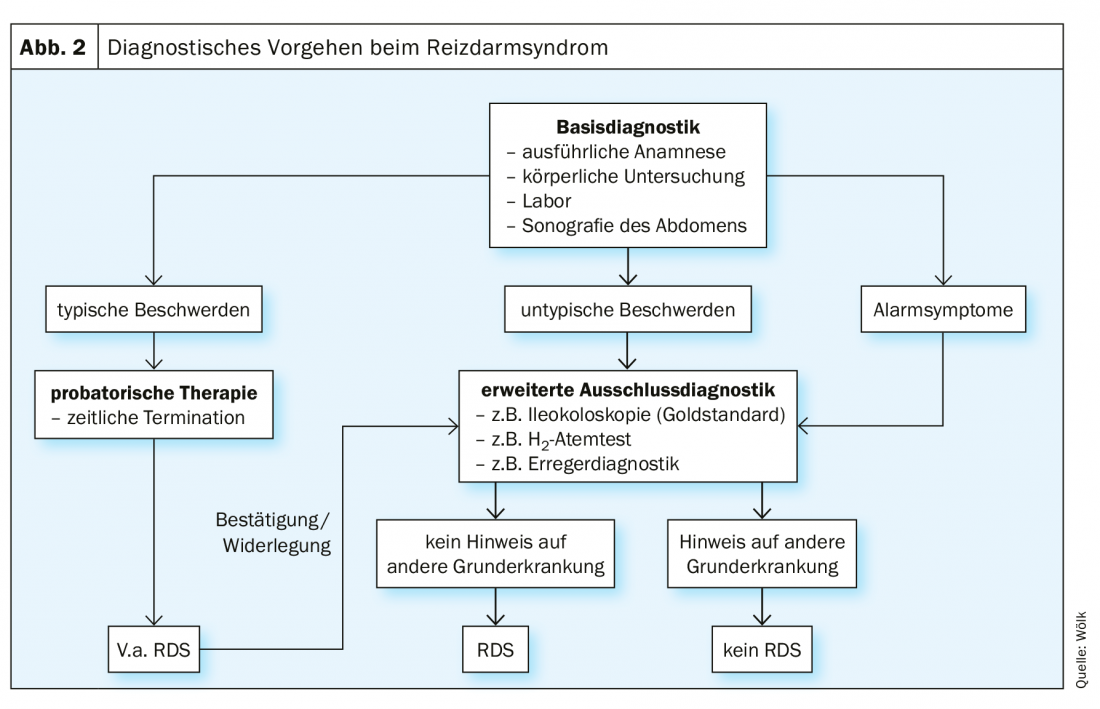

Because of the variety of symptomatic manifestations, a uniform diagnostic algorithm is of particular importance. The S3 guideline provides a clear scheme for this purpose, according to which the exclusion diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome is to be assigned after a defined basic diagnosis and the individual exclusion of relevant differential diagnoses (Fig. 2) [1]. There are many possible differential diagnoses, which is why it is necessary to proceed according to the constellation and temporal course of the symptoms [1].

In the first stage of basic diagnostics, the patient’s history is taken, during which special attention should be paid to alarm symptoms (e.g., weight loss, blood in the stool, etc.) [1]. These provide evidence for correlates of the complaints at the somatic level, which requires appropriate clarification [1]. This is followed by physical examination, collection of a baseline laboratory and sonography of the abdomen [1]. However, a definite diagnosis can only be made after individual exclusion diagnostics [1]. This includes ileocolonoscopy, especially in cases of diarrhea [1]. If typical symptoms are present, a suspected diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome should be made and probationary therapy should be started [1].

Therapy

The multifactorial pathogenesis described above opens up a wide range of therapeutic options, including general, pharmacological and psychological measures. However, this also complicates the formulation of general therapy recommendations. Of particular importance in the treatment of IBS is the trusting doctor-patient relationship [1,26]. Thus, in the spirit of shared decision making, the best therapeutic strategy can be elicited [27]. An initial psychoeducational interview forms the basis for this [26]. Treatment goals could be defined as symptom relief and improved quality of life, as only 10% of patients achieve complete freedom from symptoms [28]. Therapeutic options are divided into three categories below.

Lifestyle and diet modification

Balanced lifestyle: Regarding lifestyle, individual adjustments should be made. Relaxing procedures and regular moderate exercise (3-5 times weekly) to stimulate colonic motility showed a positive effect on symptom severity in a randomized clinical trial (RCT) [29].

Yoga can be seen as an effective relaxation technique. Incorporating yoga into daily life is one option that showed significant improvement in symptoms, anxiety expression, and quality of life in a recent meta-analysis involving six RCTs [30].

Furthermore, attention should be paid to sufficient sleep, since sleep disturbances are also a frequent accompanying phenomenon in irritable bowel syndrome [31]. Nicotine use is not an evidence-based risk factor, but should be minimized as part of a generally healthy lifestyle [31,32]. Due to the influence of lifestyle on the HPA axis, it may affect the severity of IBS [22,23].

Dietary measures: Diet is one of the main factors associated with subjective symptom expression and reduced quality of life, for example, through avoidance and fear of specific foods [33,34]. In the case of known food intolerances, especially carbohydrate malabsorption, these should be reduced accordingly in the diet [35,36]. A gluten-reduced diet may be considered, as it can lead to symptom relief, especially in patients with elevated immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels, as shown in a meta-analysis [37,38]. However, further substantial research is needed on the exact pathomechanism. It should be noted that therapy trials should be reevaluated after three months at the latest [1].

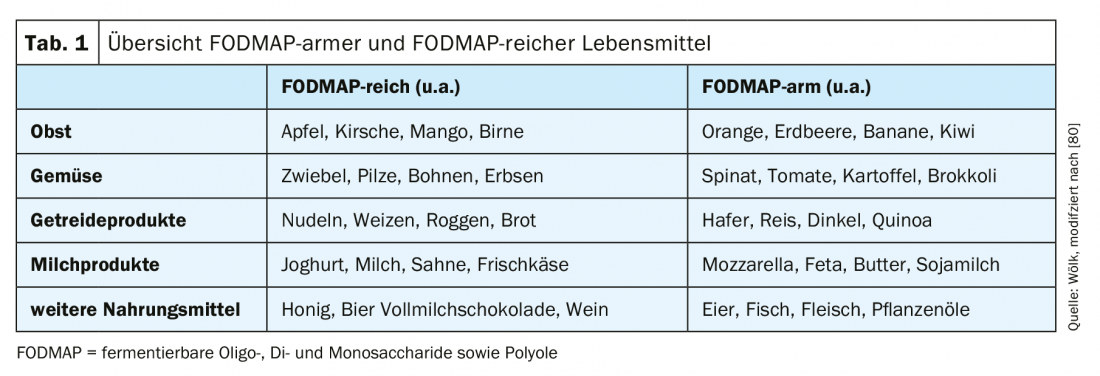

The so-called “low FODMAP diet” (“fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides as well as polyols”) is currently the focus of therapy for irritable bowel syndrome (tab. 1) . FOPMAPs are broken down and fermented in the intestine by the microbiome. As a result, gases and free fatty acids are produced, as well as increased binding of water, which can lead to worsening of symptoms via increased secretion [3,39,40]. However, especially with long-term and very strict diets, there is a risk of deficiency symptoms [41]. Meta-analyses show positive effects of low FODMAP diets, although this has often been evaluated acutely and long-term studies are pending [42,43]. A recent meta-analysis with a total of twelve studies (six RCTs and six cohort studies) showed that a reduction in FODMAPs can improve symptoms, especially abdominal pain and bloating [42]. Thus, the low FODMAP diet can be a useful therapeutic component in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome, but with attention to the supply of sufficient micronutrients, vitamins and trace elements.

Pre-, pro-, and antibiotic therapy: as of today, there is still sparse evidence for the therapeutic benefit of therapy targeting the microbiome [44]. Prebiotics are defined as indigestible food components that stimulate the growth of some strains of bacteria. Probiotics are live bacteria, which have positive influence on the microbiome, and antibiotics have the microbiome as a target, reducing gas-producing species as much as possible [44].

For an efficient treatment of the symptoms depending on the subtype, it is essential to know the necessary combinations of bacterial strains and active agents, which, however, are currently still the subject of research [44]. The heterogeneous methodology of the individual randomized clinical trials on different bacterial strains (also in combination, often at very different concentrations) makes a clear treatment recommendation difficult at present [44,45]. However, the strains Bifidobacterium (B.) infantis and B. animalis ssp. lactis against flatulence symptoms, Lactobacillus casei Shirota also against constipation (evidence level B in the S3 guideline) [1]. The antibiotic rifaximin reduces gas-forming bacterial species and may be used on a trial basis in the setting of flatulence [44,46].

Symptom-oriented pharmacotherapy

If general measures are insufficiently successful, targeted symptomatic drug therapy for the patient’s symptoms should be administered (Table 2) [1]. This differs depending on the subtype.

Pain: The first class of agents for abdominal pain are spasmolytics such as butylscopolamine [1]. The anticholinergic effect of the parasympathetic drug inhibits smooth muscle and reduces spasms and pain [47].

Alternatively or complementarily, phytotherapeutics, especially peppermint oil or cumin oil, can be tried, both of which were shown to achieve significant pain reductions in a large meta-analysis in 2008 and also according to recent analyses [1,48,49]. Peppermint oil in a special composition released in the small intestine showed good effects in irritable bowel syndrome in a recent randomized clinical trial [50]. If pain is not adequately relieved, there is the option of 5HT3 antagonists (e.g., ondansetron), which have antispasmodic and motility inhibitory effects through antiserotonergic action.

Antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants [TZA] in RDS-D subtype and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRI] in RDS-O) given at low doses also show good effects [1,3,51,52]. At higher doses, antidepressants also address psychiatric comorbidities and are used accordingly [52].

Diarrhea: Stool irregularities in terms of increased frequency and liquid consistency can be treated with medication by prolonging colonic passage and inhibiting secretion [3]. Thus, suitable substance classes are opioid receptor agonists such as the μ-opioid receptor agonist loperamide (not blood-brain-barrier mobile) [1]. According to current research, eluxadoline may be more beneficial as a μ- and κ-opioid receptor agonist as well as δ-opioid receptor antagonist because it additionally acts on pain [53]. However, therapy with eluxadoline is very costly [54].

Furthermore, bile acid resorption inhibitors (e.g., colestyramine) are a therapeutic option [1]. It has been shown that the RDS-D subtype may be associated with increased loss of bile acids [55]. Colestyramine reduces the laxative effect of free bile acids by binding them [55], which is why, in cases of marked bile acid loss, symptoms were relieved with a 96% success rate [55]. Likewise, spasmolytics, 5HT3 antagonists, and TCAs (especially amitryptiline) can be used in the RDS-D subtype [1,51,52].

Constipation: constipation is treated with medication by increasing secretion and decreasing the transit time of the colon [3]. The agents of choice are laxatives of the osmotic type (e.g., macrogol), which liquefy stool by binding water and facilitate defecation [1,48,54]. Water-soluble dietary fibers such as psyllium act on the same principle and should also be considered, while ensuring adequate fluid intake (1.5 to 2 l/d) [1,56].

To induce secretion in the colon and increase motility, lubiprostone activates chloride channels, providing an alternative [57]. Prucalopride (5HT4 agonist) and SSRIs stimulate colonic motility as proserotonergic drugs and may be tried for severe constipation refractory to therapy [1,52,58]. TCAs often cause constipation as a side effect, so they should not be used here [1,52]. As a phytotherapeutic agent, STW-5 had a beneficial effect [59].

Flatulence: Flatulence symptoms in the sense of meteorism, abdominal distension and flatulence arise on the basis of increased gas production by the microbiome and are often present as an accompanying symptom in constipation [1,3]. Gas binders (e.g., simethicone) can be an attempt at therapy, but often have limited effect [1]. Especially against flatulence, it was shown that the antibiotic rifaximin, which acts by reducing mainly gas-producing bacterial species of the intestinal flora, achieved good effects [46,60]. However, the effect was detectable only in the short term (41% improvement with treatment with rifaximin vs. 23% in the placebo group) [46,60].

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is available as a third therapeutic pillar, especially in severe and refractory courses. This is recommended in the guidelines as it addresses the multimodal etiology also on the part of psychological and social aspects [1]. The gut-brain axis already mentioned several times is bidirectional, whereby gastrointestinal complaints on the one hand have a negative effect on e.g. anxiety and depressiveness (bottom-up); on the other hand character traits, behavioral and thinking patterns as well as relationship behavior condition the perception and severity of symptoms (top-down) [61]. The psychotherapeutic approach has a particular impact on patients’ quality of life [62].

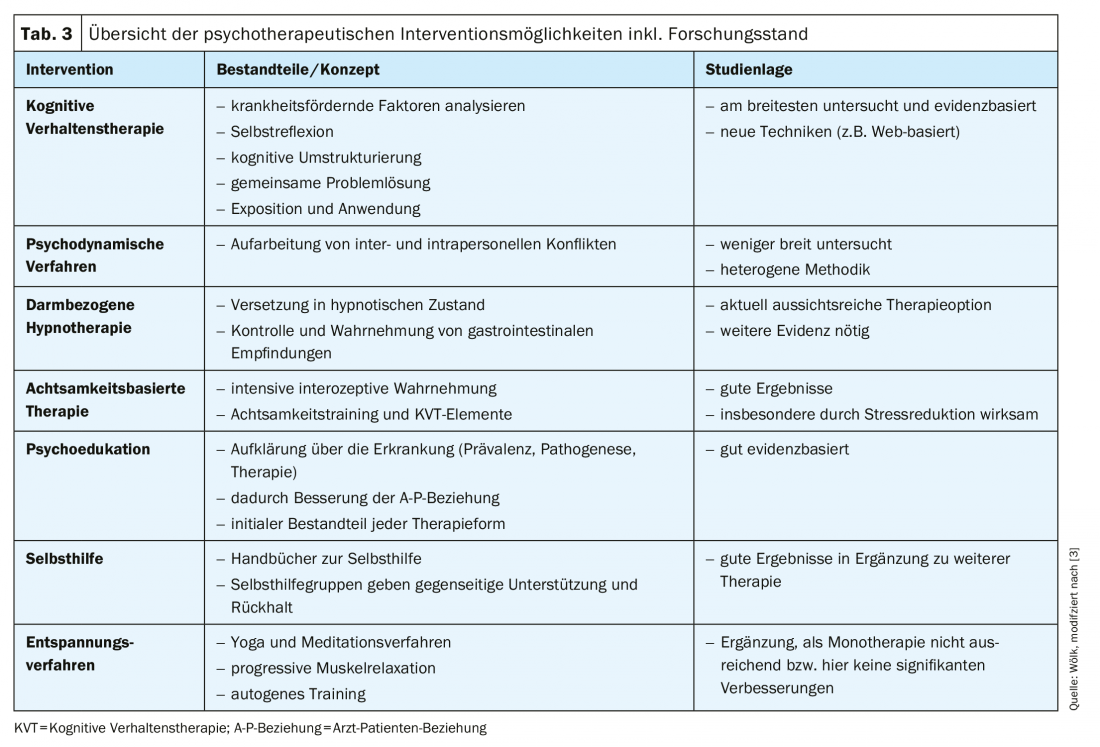

The form of psychotherapy with the greatest evidence is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [63], with a meta-analysis of 18 randomized clinical trials (n=1380) showing a number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of three patients for CBT [3,63]; this is significantly better than for pharmacological interventions, for example. Furthermore, psychodynamic methods, gut-related hypnotherapy as well as mindfulness-based therapy and other methods (psychoeducation, self-help and relaxation methods) represent psychotherapeutic starting points and are presented in the following (Tab. 3) [3].

Cognitive behavioral therapy: an important basis of successful CBT is the trusting and open relationship of the therapist to the patient [64]. For example, as early as 1995, a prospective study demonstrated that a positive physician-patient relationship reduced the need for follow-up consultations [64].

The therapist works psychoeducationally by first educating the patient about the background and linkages of the clinical picture [65]. It helps to reflect on and subsequently cognitively restructure one’s own symptom-exacerbating behavior and thinking [65]. After that, the therapy includes a joint search for solution strategies and application of these by means of exposure to stress-triggering situations [65]. This procedure resulted in a significant increase in quality of life (d=0.49) [66–68]. However, no advantage was found over other psychotherapeutic procedures [3]. The limited availability of CT in primary care conditions the need for further investigation of, for example, web-based CT offerings [69].

Psychodynamic methods: As an alternative to CT, psychodynamic procedures can be used in therapy. They aim to work through interpersonal and intrapersonal conflicts, which may be involved in the development of IBS symptoms [70].

However, the study situation of this form of therapy is not as broad as that of KVT. Also, the content of therapy in the studies is more heterogeneous than in KVT [3]. This

Heterogeneity reduces the comparability of the corresponding studies. Nevertheless, psychodynamic procedures represent a relatively inexpensive option for treating patients with primarily severe courses of illness [71].

However, a randomized clinical trial (n=257) failed to demonstrate superiority of psychodynamic therapy compared with treatment with paroxetine alone (SSRI, 20 mg/d) for three months. Both groups showed significant improvement in quality of life compared with standard therapy [1,71].

Bowel-related hypnotherapy: As a special form of hypnotherapy, this should be distinguished from the other procedures listed [3]. The goal of the altered state of consciousness is to regain control over gastrointestinal perceptions and thus improve symptoms [72].

Hypnotherapy currently presents itself as a promising psychotherapeutic intervention. In a large cohort of 1000 patients with IBS, a significant decrease in symptom severity, defined as a reduction of at least 50 points in the IBS Symptom Severity Score (IBS-SSS), was achieved in 76% of patients [73].

The NNT is four patients, and this is based on 452 patients from seven randomized clinical trials [3]. According to a recent review, up to 73% of patients respond positively to bowel-related hypnotherapy [3,72]. The disadvantages of intestinal hypnotherapy are the currently still very limited availability and the relatively high costs [3].

Mindfulness-based therapy: the last psychotherapeutic method to be considered in more detail is mindfulness-based therapy, as it particularly reduces the distress felt as a result of the illness [74]. The combination of mindfulness-related and cognitive elements trains perception and self-reflection by enabling better therapy after intensive interoceptive awareness of symptoms [3]. The therapy usually covers a period of eight weeks [3,74].

Unfortunately, the available studies are not very comprehensive. A randomized clinical trial in 75 women showed that the therapy resulted in a significant reduction of symptoms (26.4% vs. 6.2%) compared to the control group and that the improvement persisted after three months, while another clinical trial described an equalization of symptom improvement with the therapy compared to the control group after six months (n=90). [74,75]. This suggests a rather short-term effect of this form of therapy. However, methodological weaknesses reduce the validity of the studies, which is why further research is indicated. For example, a pilot study this year showed promising results for mindfulness-based therapy (higher stress reduction than dialectical behavioral therapy) [76].

Other alternatives: Alternative psychotherapeutic interventions are complementary to the listed therapies. Psychoeducation, self-help, and relaxation techniques are recommended as options in the guidelines [1].

Psychoeducation in the sense of explaining the biopsychosocial genesis as already described is important for the functional doctor-patient relationship and for the patient to feel perceived and understood with his suffering [13,64].

Self-help is provided, for example, by manuals, which can be recommended according to current studies (significant, by 60%, reduction in physician consultations when using a manual after one year) [1,77]. Relaxation techniques can be used in combination; there is no convincing evidence for monotherapy [1,78].

Outlook

Irritable bowel syndrome is a worldwide prevalent multifactorial disease [12]. The possible pathogenetic factors entail a variety of therapeutic approaches. The roles of diet (e.g., FODMAP content) and microbiome are to be considered important in this regard, as prebiotics, probiotics, antibiotics, and possibly fecal microbiome transfer (FMT) can be used to influence the bacterial flora. However, FMT should be viewed with caution, as studies on it are still lacking and only limited success has been shown within a randomized clinical trial to date [79]. Furthermore, a variety of drug options are available for symptomatic therapy. Although psychotropic drugs are not very popular with patients (and often with physicians), meta-analyses show them to be very favorable treatment options. Psychotherapy should be offered especially to patients with severe courses and psychological comorbidities. KVT, psychodynamic psychotherapy, but also bowel-related hypnotherapy and mindfulness-based therapy are suitable methods in this context.

Take-Home Messages

- The genesis of IBS is multifactorial and can be explained by the biopsychosocial model of disease.

- Lifestyle modifications (e.g., stress reduction) should occur as a basic therapy.

- Bowel-related hypnotherapy is still difficult to implement due to limited availability.

- The choice of the form of therapy should be made together with the patient.

- Psychotherapy should be offered for severe courses and psychological comorbidities.

Literature:

- Layer P, et al: Irritable bowel syndrome: German consensus guidelines on definition, pathophysiology and management. Z Gastroenterol, 2011. 49(2): 237-293.

- Mearin F, et al: Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology, 2016.

- Enck P, et al: Irritable bowel syndrome. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2016. 2: 16014.

- Lacy BE, Patel NK: Rome Criteria and a Diagnostic Approach to Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Clin Med, 2017. 6(11).

- Lee YY, Annamalai C,Rao SSC: Post-Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep, 2017. 19(11): 56.

- Lewis SJ. Heaton KW: Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol, 1997. 32(9): 920-924.

- Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR: Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology, 2002. 122(4): 1140-1456.

- Ford AC, et al: Irritable bowel syndrome: a 10-yr natural history of symptoms and factors that influence consultation behavior. Am J Gastroenterol, 2008. 103(5): 1229-1239; quiz 1240.

- Sibelli A, et al: A systematic review with meta-analysis of the role of anxiety and depression in irritable bowel syndrome onset. Psychol Med, 2016. 46(15): 3065-3080.

- Lovell RM, Ford AC: Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2012. 10(7): 712-721.e4.

- Lovell RM, Ford AC: Effect of gender on prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol, 2012. 107(7): 991-1000.

- Thomas G, Grobe SS, Szecsenyi J: BARMER-Arztreport 2019 in Schriftenreihe zur Gesundheitsanalyse. 2019.

- Tanaka Y, et al: Biopsychosocial model of irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2011. 17(2): 131-139.

- Carroll IM, et al: Alterations in composition and diversity of the intestinal microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2012. 24(6): 521-530, e248.

- Carroll IM, et al: Molecular analysis of the luminal- and mucosal-associated intestinal microbiota in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2011. 301(5): G799-807.

- Moser G, Fournier C, Peter J: Intestinal microbiome-gut-brain axis and irritable bowel syndrome. Wien Med Wochenschr, 2018. 168(3-4): 62-66.

- Zhou Q, Zhang B, Verne GN: Intestinal membrane permeability and hypersensitivity in the irritable bowel syndrome. Pain, 2009. 146(1-2): 41-6.

- Piche T, et al: Impaired intestinal barrier integrity in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: involvement of soluble mediators. Gut, 2009. 58(2): 196-201.

- Barbara G, et al: The immune system in irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2011. 17(4): 349-359.

- Larsson MH, et al: Elevated motility-related transmucosal potential difference in the upper small intestine in the irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2007. 19(10): 812-820.

- Elsenbruch S, et al: Patients with irritable bowel syndrome have altered emotional modulation of neural responses to visceral stimuli. Gastroenterology, 2010. 139(4): 1310-1319.

- Walter SA, et al: Pre-experimental stress in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: high cortisol values already before symptom provocation with rectal distensions. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2006. 18(12): 1069-1077.

- FitzGerald LZ, Kehoe, Sinha K: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation in women with irritable bowel syndrome in response to acute physical stress. West J Nurs Res, 2009. 31(7): 818-836.

- O’Mahony SM, et al: Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Stress-Related Psychiatric Co-morbidities: Focus on Early Life Stress. Handb Exp Pharmacol, 2017. 239: 219-246.

- Whitehead WE, et al: Learned illness behavior in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer. Dig Dis Sci, 1982. 27(3): 202-208.

- Di Palma JA, Herrera JL: The role of effective clinician-patient communication in the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2012. 46(9): 748-751.

- Towle A, Godolphin W: Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision making. Bmj, 1999. 319(7212): 766-771.

- Hauser W, et al: Functional bowel disorders in adults. Dtsch Arztebl Int, 2012. 109(5): 83-94.

- Johannesson E, et al: Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol, 2011. 106(5): 915-922.

- Schumann D, et al: Effect of Yoga in the Therapy of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2016. 14(12): 1720-1731.

- Tu Q, et al: Sleep disturbances in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2017. 29(3).

- Sirri L, Grandi S, Tossani E: Smoking in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review. J Dual Diagn, 2017. 13(3): 184-200.

- Bohn L, Storsrud S, Simren M: Nutrient intake in patients with irritable bowel syndrome compared with the general population. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2013. 25(1): 23-30.e1.

- Bohn L, et al: Self-reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol, 2013. 108(5): 634-641.

- Goldstein R, Braverman D, Stankiewicz H: Carbohydrate malabsorption and the effect of dietary restriction on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and functional bowel complaints. Isr Med Assoc J, 2000. 2(8): 583-587.

- Shepherd SJ, et al: Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2008. 6(7): 765-771.

- Wahnschaffe U, et al: Predictors of clinical response to gluten-free diet in patients diagnosed with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2007. 5(7): 844-850; quiz 769.

- Atkinson W, et al: Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut, 2004. 53(10): 1459-1464.

- Cummings JH, Macfarlane GT: Role of intestinal bacteria in nutrient metabolism. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 1997. 21(6): 357-365.

- Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ: Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2010. 25(2): 252-258.

- Catassi G, et al: The Low FODMAP Diet: Many Question Marks for a Catchy Acronym. Nutrients, 2017. 9(3).

- Altobelli E, et al: Low-FODMAP Diet Improves Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 2017. 9(9).

- Varju P, et al: Low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) diet improves symptoms in adults suffering from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) compared to standard IBS diet: A meta-analysis of clinical studies. PLoS One, 2017. 12(8): e0182942.

- Ford AC, et al: Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and antibiotics in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2018. 48(10): 1044-1060.

- Didari T, et al: Effectiveness of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: Updated systematic review with meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol, 2015. 21(10): 3072-3084.

- Pimentel M, et al: Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med, 2011. 364(1): 22-32.

- Krueger D, et al: Effect of hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan(R)) on cholinergic pathways in the human intestine. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2013. 25(8): e530-539.

- Ford AC, Lacy BE, Talley NJ: Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med, 2017. 376(26): 2566-2578.

- Ford AC, et al: Effect of fiber, antispasmodics, and peppermint oil in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj, 2008. 337: a2313.

- Cash BD, Epstein MS, Shah SM: A Novel Delivery System of Peppermint Oil Is an Effective Therapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptoms. Dig Dis Sci, 2016. 61(2): 560-571.

- Garsed K, et al: A randomised trial of ondansetron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Gut, 2014. 63(10): 1617-1625.

- Moret C, Briley M: Antidepressants in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2006. 2(4): 537-548.

- Lacy BE, et al: Eluxadoline Efficacy in IBS-D Patients Who Report Prior Loperamide Use. Am J Gastroenterol, 2017. 112(6): 924-932.

- Defrees DN, Bailey J: Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Prim Care, 2017. 44(4): 655-671.

- Wedlake L, et al: Systematic review: the prevalence of idiopathic bile acid malabsorption as diagnosed by SeHCAT scanning in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009. 30(7): 707-717.

- Zuckerman MJ: The role of fiber in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: therapeutic recommendations. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2006. 40(2): 104-108.

- Li F, et al: Lubiprostone Is Effective in the Treatment of Chronic Idiopathic Constipation and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Mayo Clin Proc, 2016. 91(4): 456-68.

- Corsetti M, Tack J: New pharmacological treatment options for chronic constipation. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2014. 15(7): 927-941.

- Madisch A, et al: Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with herbal preparations: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-center trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2004. 19(3): 271-279.

- Pimentel M: Review article: potential mechanisms of action of rifaximin in the management of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2016. 43 Suppl 1: 37-49.

- Fond G, et al: Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2014. 264(8): 651-660.

- Guthrie E, et al: A randomised controlled trial of psychotherapy in patients with refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Psychiatry, 1993. 163: 315-321.

- Laird KT, et al: Short-term and Long-term Efficacy of Psychological Therapies for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2016. 14(7): 937-947.e4.

- Owens DM, Nelson DK, Talley NJ: The irritable bowel syndrome: long-term prognosis and the physician-patient interaction. Ann Intern Med, 1995. 122(2): 107-112.

- Kinsinger SW: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome: current insights. Psychology research and behavior management, 2017. 10: 231-237.

- Laird KT, et al: Comparative efficacy of psychological therapies for improving mental health and daily functioning in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 2017. 51: 142-152.

- Radziwon CD, Lackner JM: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for IBS: How Useful, How Often, and How Does It Work? Current Gastroenterology Reports, 2017. 19(10): 49.

- Li L, et al: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res, 2014. 77(1): 1-12.

- Kawanishi H, et al: Cognitive behavioral therapy with interoceptive exposure and complementary video materials for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial in Japan. Biopsychosoc Med, 2019. 13: 14.

- Palsson OS, Whitehead WE: Psychological Treatments in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Primer for the Gastroenterologist. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2013. 11(3): 208-216.

- Creed F, et al: The cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy and paroxetine for severe irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology, 2003. 124(2): 303-317.

- Peters SL, Muir JG, Gibson PR: Review article: gut-directed hypnotherapy in the management of irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2015. 41(11): 1104-1115.

- Miller V, et al: Hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome: an audit of one thousand adult patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2015. 41(9): 844-855.

- Gaylord SA, et al: Mindfulness training reduces the severity of irritable bowel syndrome in women: results of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol, 2011. 106(9): 1678-1688.

- Zernicke KA, et al: Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome symptoms: a randomized wait-list controlled trial. Int J Behav Med, 2013. 20(3): 385-396.

- Mohamadi J, Ghazanfari F, Drikvand FM: Comparison of the Effect of Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy and Positive Psychotherapy on Perceived Stress and Quality of Life in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychiatr Q, 2019. 90(3): 565-578.

- Robinson A, et al: A randomised controlled trial of self-help interventions in patients with a primary care diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut, 2006. 55(5): 643-648.

- Ford AC, et al: Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut, 2009. 58(3): 367-378.

- Johnsen PH, et al: Faecal microbiota transplantation versus placebo for moderate-to-severe irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, single-centre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018. 3(1): 17-24.

- Storr M: The nutritional guide to the FODMAP diet: the somewhat different diet for irritable bowel syndrome, wheat intolerance and other digestive disorders. 2017: W. Zuckschwerdt Publishers.

HAUSARZT PRAXS 2019; 14(9): 9-15