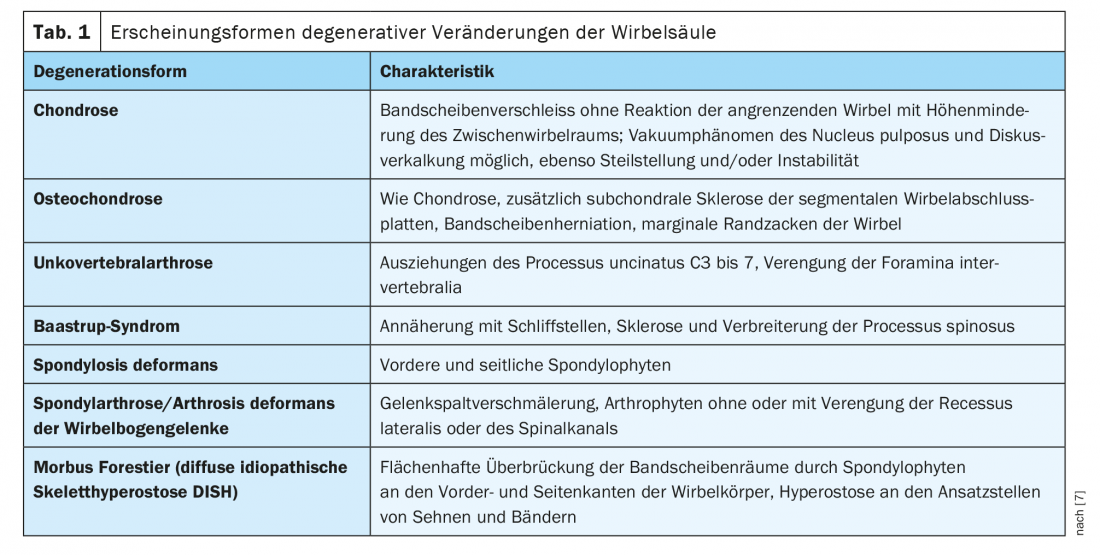

Also known as spondylosis hyperostotica , idiopathic degenerative vertebral pathology is the most common noninflammatory spinal disease, with prevalence increasing in an age-correlated manner. Characteristic clinical features are pronounced hyperostoses on the anterior and lateral surfaces of the vertebral bodies. The intervertebral disc spaces are bridged in the form of braces, which leads to stiffening.

With increasing age, degenerative changes in the musculoskeletal system increase, associated with pain, deformity and restricted movement. A global overview of the forms of arthrosis deformans of the spine in the broadest sense is given in Table 1. [7].

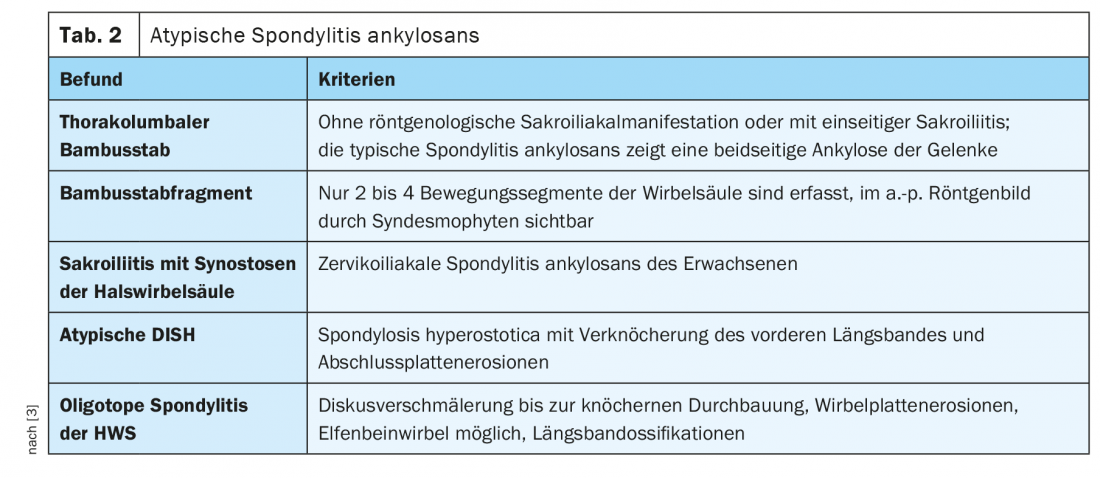

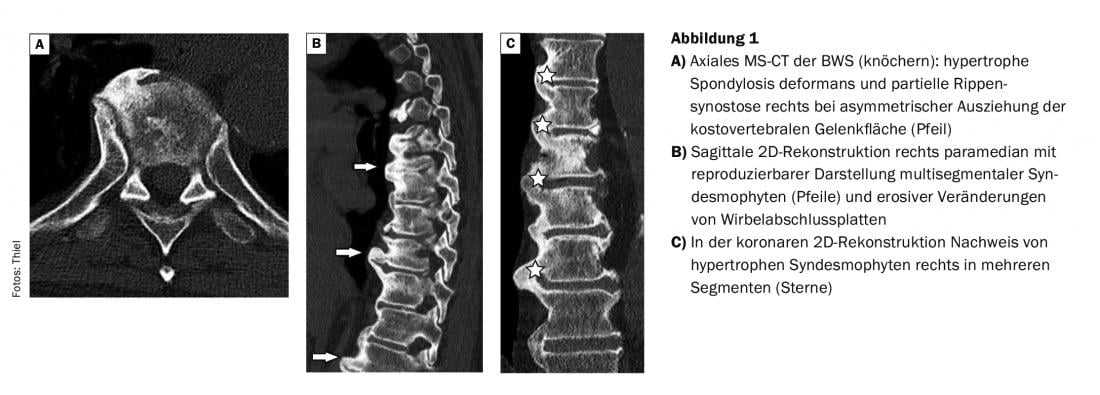

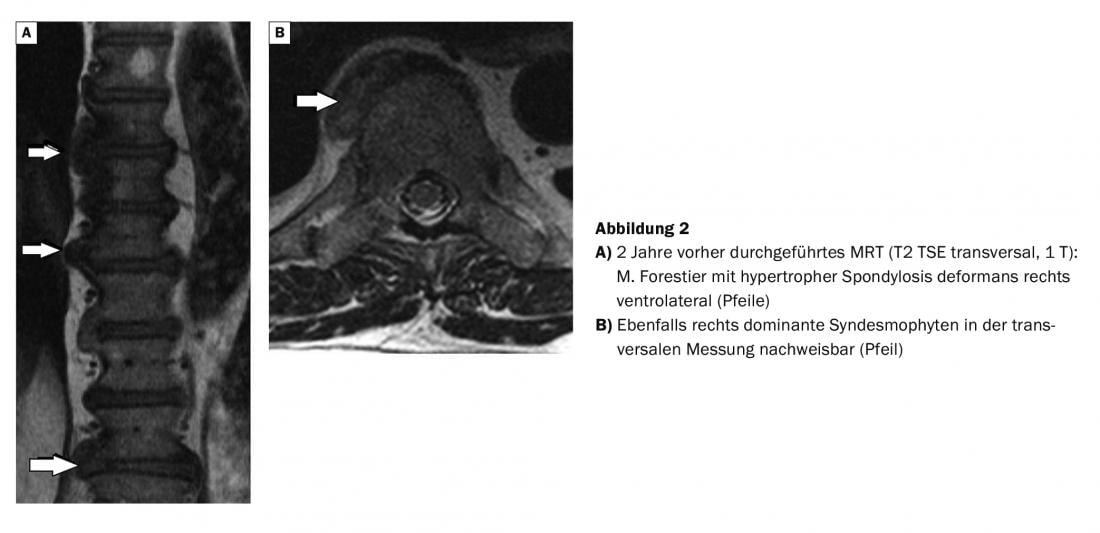

In a previous article, generalized spondylophytic changes of the spine were reported. Forestier’s disease as hypertrophic spondylosis deformans, especially of the thoracic spine, may thereby also indicate a manifestation of DISH syndrome (Disseminated Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis). A famous German poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, had skeletal changes of a M. Forestier [14]. In addition to the pronounced spondylophytes of the vertebrae, which are primarily detectable on the right side of the thoracic spine, longitudinal ligamentous ossifications are also found [1,5,10,13]. Hyperostotic changes may occur at the costovertebral heads, associated with asymmetric extensions of the costovertebral articular surfaces without significant arthritic changes in the articular areas [4]. This disease, also known as atypical ankylosing spondylitis [3], can be differentiated from true ankylosing spondylitis by certain manifestations in imaging studies, not only by laboratory chemistry through HLA B-27 ( Table 2).

Several metabolic changes may be associated with DISH [4,11], such as obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, gout, glucose intolerance, or hyperinsulinemia. The changes are progressive with increasing age. This was shown by a Japanese study that found a clustering of vertebragenic changes of DISH in over 3000 patients from age 40 to a peak around 70 years with a prevalence of 8.7%.

In addition to osseous-related symptoms, such as limited mobility, various other accompanying symptoms may occur, such as dysphonia, dysphagia, and dyspnea with sleep apnea [2], which requires special accompanying management, up to and including surgical treatment [6,12].

Computed tomographic examination has proven successful in detecting calcification of tendons and ligaments. Axial scans of multislice CT with multiplanar reconstructions depict the exact extent of hyperostoses.

Magnetic resonance imaging examination very sensitively demonstrates edematous bone changes within the inflammatory-active situation of the skeletal system, adipose tissue infiltrations, ankylosing vertebral endplates, and inflammatory joint as well as tendon changes [15].

Case study

The case report shows the images of an MS-CT of the thoracic spine of an over 80-year-old man with back pain who presented with Forestier’s disease (Fig. 1) .

In comparison with the MRI images (Fig. 2), which were made 2 years earlier, the better representation of the bony structures in the CT can be attested. In the patient with prostate carcinoma, skeletal scintigraphy revealed multisegmental marginal multiple storage in the region of several thoracic vertebrae, which could be verified as distinct syndesmophytes.

Take-Home Messages

- Forestier’s disease shows pronounced vertebral edge pull-outs, primarily on the right side of the thoracic spine, as well as longitudinal ligamentous ossifications.

- Detection of Forestier’s disease may indicate DISH.

- In DISH, calcifications of tendons, ligaments, capsules of various joints, and bony pull-outs of the insertion sites on long bones are found.

- Several metabolic changes are associated with DISH.

- In the thoracic spine, hypertrophic spondylophytic vertebral changes are already detectable by radiographs and are more verifiable by CT than by MRI.

Literature:

- Bittner RC, Rossdeutscher R: Guide to radiology. Stuttgart, Jena, New York: Gustav Fischer Verlag 1996; 196.

- Darakjian A, et al: Refractory Obstructive Sleep Apnea in a Patient with Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis. Case Rep Otolaryngol 2016; 2016: 4906863.

- Dihlmann W, Stäbler A: Joints – vertebral connections. 4th, completely revised and expanded edition. Stuttgart, New York: Georg Thieme Verlag 2011; 481-483.

- Freyschmidt J: Skeletal diseases. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag 1993; 114-116.

- Holgate RL, Steyn M: Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: diagnostic, clinical, and patheological consideration. Clin Anat 2016; 29(7): 870-877.

- Kondo Y, et al: Airway Management in a Patient with Forestier’s Disease. Masui 2016; 65(4): 402-406.

- Lasserre A: Memorix radiographic diagnostics. Weinheim: Chapman & Hall GmbH 1997; 339.

- Mori K, et al: Prevalence of thoracic diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) in Japanese: results of chest CT-based cross-sectional study. J Orthop Sci 2017; 22(1): 38-42.

- Najib J, et al: Forestier’s disease presenting with dysphagia and disphonia. Pan Afr Med J 2014; 17: 168.

- Nascimento FA, et al: Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: A review. Surg Neurol Int 2014; 5(Suppl 3): S122-125.

- Pillai S, Littlejohn G: Metabolic factors in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis – a review of clinical data. Open Rheumatol J 2014; 8: 116-128.

- Tan MS, et al: Surgical treatment for Forestier disease: a report of 8 cases. Zhongguo Gu Shang 2015; 28(1): 78-81.

- Thiel HJ: Cross-sectional diagnosis of the spine (1.15). Degenerative changes: Forestier’s disease. MTA Dialog 2017; 6(18): 486-489.

- Ullrich H: Goethe’s skull and skeleton. Anthropol Anz 2002; 60(4): 341-368.

- Weiss BG, Bachmann LM, Pfirrmann CW, et al: Whole Body Magnetic Resonance Imaging Features in Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis in Conjunction with Clinical Variables to Whole Body MRI and Clinical Variables in Ankylosing Spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2016 Feb;43(2): 335-342.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(12): 44-46