Benign positional vertigo, or somewhat more correctly benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPLS), is the most common cause of dizziness, accounting for 20-30% of all patients who seek medical attention for vertigo. Since it can be treated well in a high percentage by simple positioning maneuvers and is curable in many cases, almost every physician should actually be able to relieve his patients of this very unpleasant clinical picture. The following article provides tips regarding diagnosis and therapy.

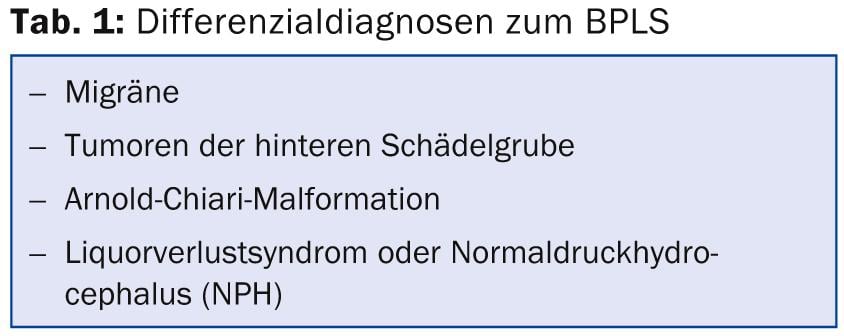

According to a study by Brevern et al. In 2007 [1], of 1003 patients surveyed, only 8% received effective therapy for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPLS). For good treatment, the most important thing is to accurately identify the affected archway so that the optimal release maneuver for that archway can be performed. Furthermore, in case of anamnestically relatively typical BPLS but absent or atypical nystagmus, possible differential diagnoses (Tab. 1) should also be considered. BPLS should never be confused with other vestibular disorders such as Meniere’s disease or acute vestibulopathy, because the distinction is simple in principle.

Pathology of the BPLS

BPLS is triggered by otoconia, which are small (5-35 μm) crystal-like bodies of predominantly calcium carbonate that sit on the macula of the utricle, where they enhance the perception of gravity and linear acceleration. When these particles become dislodged, they can fall into the archways open to the utricle. This affects a posterior vertical arch in 80-90% of cases, a horizontal arch in about 10%, and rarely an anterior vertical arch. In the archways, they are always pulled by gravity to the lowest point of the archway, and their descent triggers a fluid movement that deflects the cupula. This is interpreted by the brain as an irritation of the corresponding arcuate duct and is perceived as rotational vertigo, since the arcuate ducts measure rotational movements of the head. This spinning dizziness lasts only as long as the particles trigger a fluid flow that deflects the cupula. The spinning dizziness as well as the observed nystagmus are therefore of short duration. Only if the particles adhere to a cupula, which rarely happens and has so far only been described for horizontal arcades, vertigo and nystagmus last for a long time. Since it also takes a short time for the particles to trigger flow, there is very often a latency of a few seconds before dizziness and nystagmus occur. Often this latency is reported to be significantly shorter or even absent for the horizontal arcades, but this can also occur for the posterior arcades.

Diagnosis

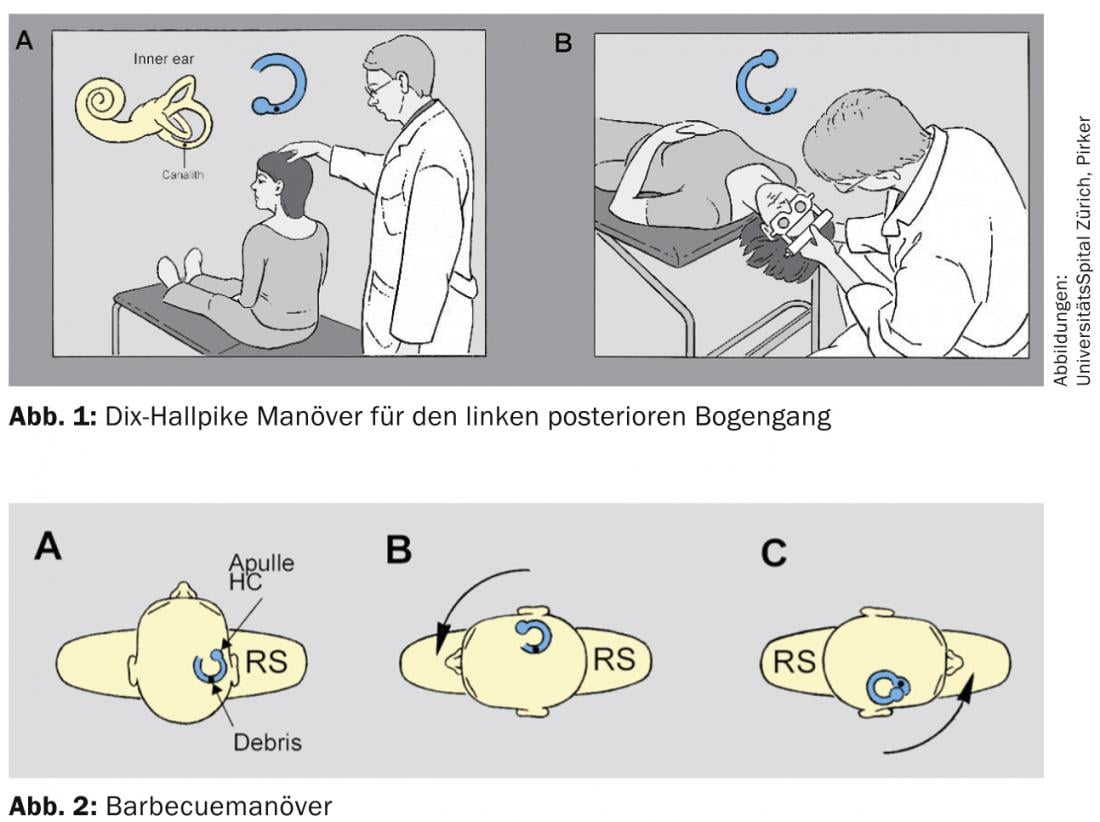

For the diagnosis of BPLS, an accurate medical history is important first. The question of whether dizziness is continuous or intermittent is often answered incorrectly, as many patients experience dizziness every time they move their head. Because they perform these movements very often, they describe the dizziness as persistent. Here, the question of triggering by head position changes is particularly important. If this is confirmed, then specific questions should be asked about vertigo triggered by lying in bed and head rotation. If only one head rotation to one side is indicated as triggering, then the posterior arch is probably affected on the side to which the head is rotated. If vertigo is reported when the head is turned to either side while lying down, then a horizontal archway should be suspected, since canalolithiasis of a horizontal archway always results in BPLS in both directions. However, the vertigo is usually more severe when the head is turned to the diseased side, because in this case the canaloliths trickle onto the cupula, which corresponds to stimulation. According to Ewald’s second law, this always triggers a stronger response than inhibition. However, with the history, only the presumption of the affected archway is secured. The clinical examination is decisive. For this purpose, there is the Dix-Hallpike maneuver [2] for the vertical arcades and the “barbecuing maneuver” [3] for the horizontal arcades (Figs. 1 and 2).

Dix-Hallpike maneuver for the left posterior arcuate: When the posterior arcuate is affected, a predominantly rotatory nystagmus occurs in the Hallpike maneuver, i.e., the eyes rotate around the visual axis, with the direction of movement of the superior pole of the eye determining the direction of nystagmus during the fast phase. Thus, in canalolithisis of the left posterior arch, the superior pole of the eye beats to the inferior ear.

Barbecuemaneuver: In canalolithiasis of a horizontal arcuate duct, horizontal beating nystagmus occurs when the head is turned to either side. In most cases, this is geotropic, i.e. it strikes towards the floor on both sides. He also changes the direction of the stroke with the position of the head. The side where the nystagmus beats stronger and usually the dizziness is stronger is the affected side. Even with the patient in the supine position with the head straight, mild horizontal nystagmus often occurs. This usually already indicates the affected side. At least the side to which this beats is usually the one affected.

Important: almost purely torsional nystagmus speaks for the posterior arch of the inferior ear. During straightening, this torsional nystagmus changes in the opposite direction. Horizontal nystagmus is indicative of horizontal arcuate gait.

In rare cases, posterior and horizontal arcades of both sides are also affected, which may cause mixed nystagmus. Depending on the medical history, we always examine the presumably affected arcade first. If canalolithiasis is confirmed, the diagnostic maneuver is immediately followed by a rescue maneuver. If the nystagmus is not typical of canalolithiasis of the corresponding archway, then one can still complete the extrication maneuver, but should think of the differential diagnoses. If the symptoms do not improve after unsuccessful extrication maneuvers, the differential diagnoses (Tab. 1) should always be considered and/or the patient should be referred to an appropriate specialist.

Treatment

After the diagnosis of the affected archway:

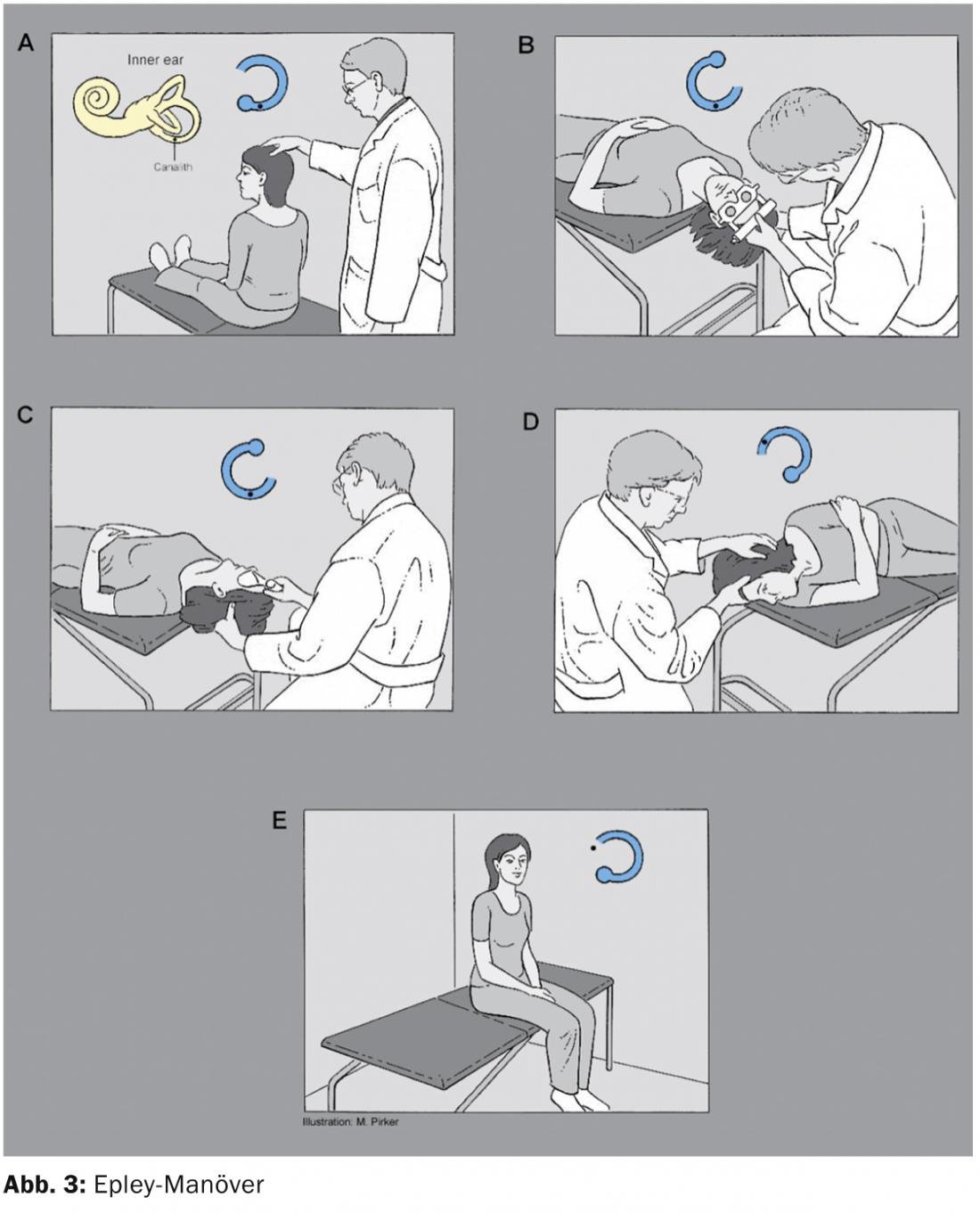

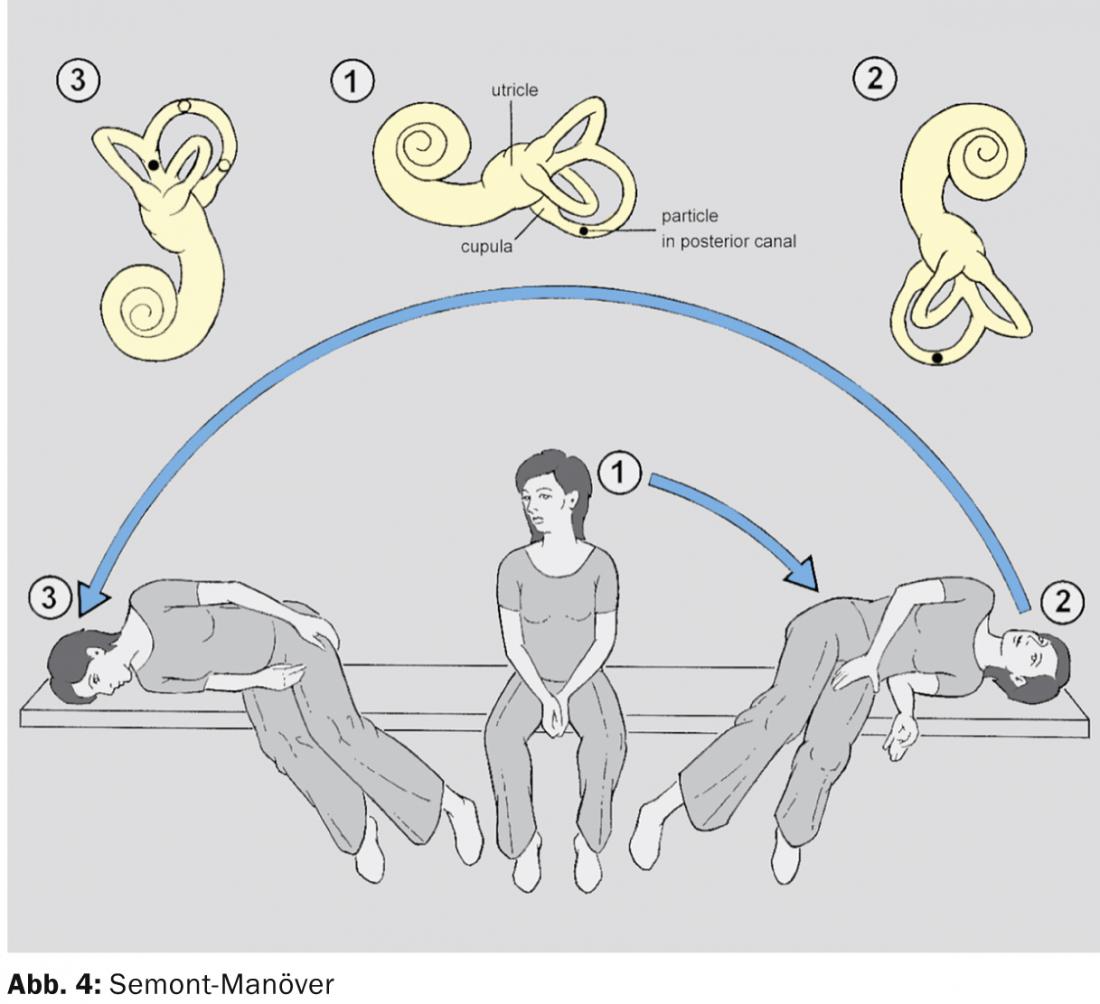

Posterior archway: there is the Epley maneuver [4] and the Semont maneuver [5] (Figs. 3 and 4).

Both have about equally good cure rates. However, the Semont maneuver requires rapid storage from one side to the other, while the Epley maneuver can also be performed slowly. In French-speaking countries, the Semont maneuver is often used, but in German and English-speaking countries, the Epley maneuver is mostly used. Also, when the patient repeats the positioning maneuver himself, fewer errors are made by him during the Epley maneuver.

The Epley maneuver can also be easily repeated by the patient on their own at home if the treatment at the doctor’s office did not help immediately or in case of recurrence, which occurs more often within the first few weeks.

When positioning according to Semont, care must be taken to ensure that the head position remains the same in all body positions, i.e., in the case of canalolithiasis of the left posterior arch, always a head rotated 45° to the right. That is, in the first lateral position the patient looks up, in the second down. This is very often done incorrectly when patients repeat the maneuver independently, which is why we prefer the Epley maneuver.

Modifications or variations of the maneuvers have been described, but better success than the original maneuvers has not yet been demonstrated. Vibration of the mastoid during storage, which was also supposed to loosen particles still adhering to the wall, has not yet resulted in any demonstrable benefit. There have been several studies that investigated a specific positional restriction after a successful reduction maneuver, thereby reducing the recurrence rate. No significant effect was found in any of the studies, but a new overall analysis of all of them found a significant effect of avoiding certain positions. Accordingly, patients should nevertheless sleep with their head slightly elevated for a few days [6].

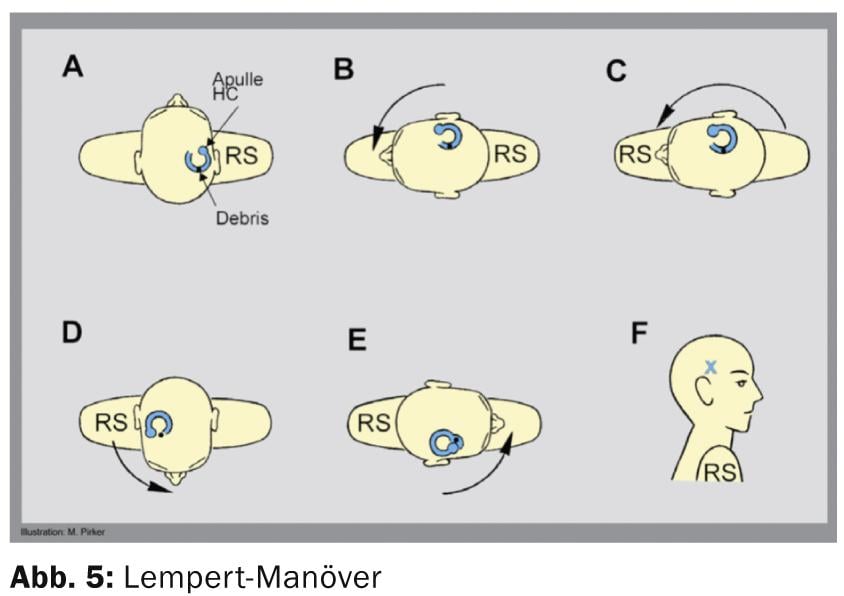

Horizontal archway: After diagnosis of the affected archway, it is treated by the reduction maneuver according to Lempert [7] or by a Guffoni maneuver [8]. In geotropic nystagmus, the side on which vertigo and/or nystagmus are more pronounced is affected. In apogeotropic nystagmus, an attempt should first be made to convert it to geotropic nystagmus by repeatedly turning the head from left to right and back, which can then also be treated with the Lempert maneuver (Fig. 5).

If the Lempert maneuver is unsuccessful or initial, the Gufoni maneuver can also be performed. This is applicable to both geotropic and apogeotropic horizontal position nystagmus. It is only necessary to pay attention to which position the nystagmus is stronger, i.e. when the head is turned to the right or to the left. In any case, the Gufoni maneuver should be made on the side with the low positional nystagmus. In geotropic positional nystagmus, the patient thus first lies down on the healthy side and after about ten seconds turns his head downward by about 45°. He remains in this position for about 30 seconds and can then stand up. This maneuver showed a 67% cure rate in a study by Casani et al [9].

In apogeotropic nystagmus, the patient lies down on the affected side, which is also the one with the weaker nystagmus. After 10-30 seconds, he then turns his head upwards by 45° and remains in this position for about two minutes.

If the Gufoni maneuver is also unsuccessful, the patient can be asked to lie on the healthy ear for as long as possible, at least three hours according to our experience, although 12 hours are mentioned in the literature, but this is unlikely to be sustained. This treatment is described as “forced prolonged position”. It is often successful even after several unsuccessful storage maneuvers. A recovery of over 90% was described in a study of 35 patients [10]. We advise patients to fall asleep on their healthy side and, if possible, to remain lying on this side. Of course, it can also be performed right at the beginning in addition to the storage maneuvers.

PD Stefan Hegemann, MD

Arianne Monge Naldi, M.D.

Literature:

- Von Brevern M, et al: Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007; 78: 710-715.

- Dix MR, Hallpike CS: The pathology symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Proc R Soc Med 1952; 45: 341-354.

- Baloh RW, Jacobson K, Honrubia V: Horizontal semicircular canal variant of benign positional vertigo. Neurology 1993; 43: 2542-2549.

- Epley JM: The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992; 107: 399-404.

- Semont A, Freyss G, Vitte E: Curing the BPPV with a liberatory maneuvre. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 1988; 42: 290-293.

- Hunt WT, Zimmermann EF, Hilton MP: Modifications of the Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 18; 4:CD008675.

- Lempert T: Horizontal benign positional vertigo. Neurology 1994 Nov; 44: 2213-2214.

- Gufoni M, Mastrosimone L, Di Nasso F: Repositioning maneuver in benign paroxysmal vertigo of horizontal semicircular canal. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 1998; 18: 363-367.

- Casani AP, et al: The treatment of horizontal canal positional vertigo: our experience in 66 cases. Laryngoscope 2002; 112: 172-178.

- Vannucchi P, Giannoni B, Pagnini P: Treatment of horizontal semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Vestib Res 1997; 7: 1-6.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- An accurate history is central to the diagnosis of BPLS. The subsequent clinical examination should confirm the assumption of the affected archway (maneuver according to Dix-Hallpike for the vertical archways, “barbecuing maneuver” for the horizontal archways).

- With the described positioning maneuvers (Epley, Semont, Lempert, Gufoni), there is a recovery rate of >90% of affected persons after about three days.

- In case of persistent complaints, we recommend referral to a specialist consultation.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(3): 16-20