The management of gastroesophageal reflux disease is not a trivial matter. Often, symptoms correlate only slightly with severity. In which cases should endoscopy be performed?

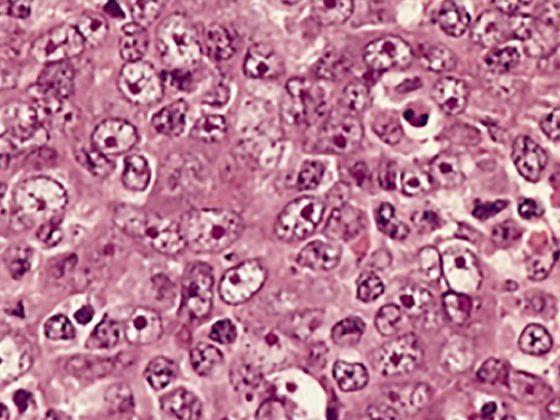

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common cause of upper gastrointestinal tract symptoms [1]. A benign complication of GERD is reflux esophagitis, which increases the risk for ulcer or peptic stricture. A potentially malignant complication is the development of Barrett’s esophagus, a precancerous condition for the development of adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus (Barrett’s carcinoma). Typical symptoms of reflux syndrome include heartburn, a burning sensation or burning pain usually rising from the epigastrium, regurgitation, and acid regurgitation. Other common manifestations include upper abdominal pain and sleep disturbances due to nocturnal reflux. Visible inflammation of varying severity (Los Angeles grades A through D) and peptic stenosis may develop in the esophagus.

Monitoring of risk groups recommended

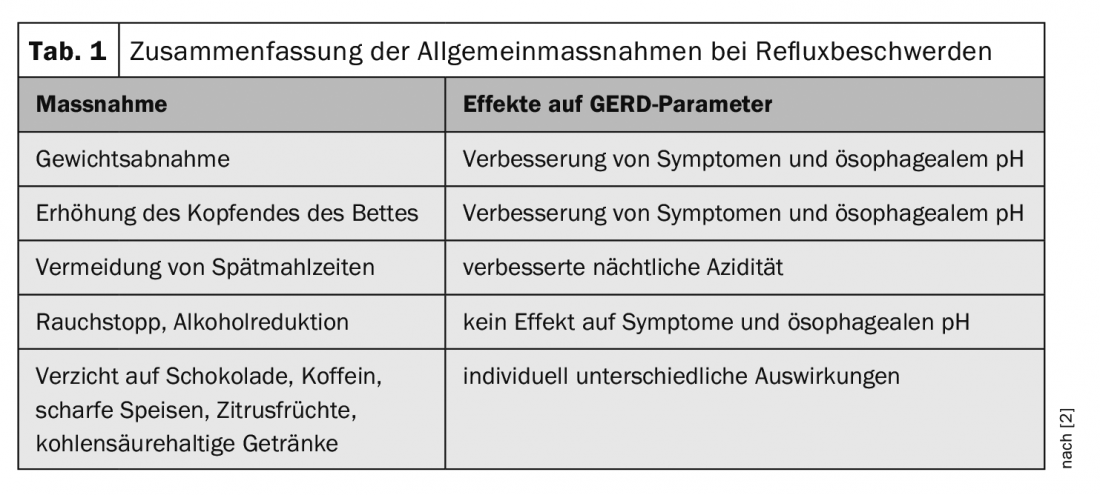

The symptoms of reflux disease do not correlate with the degree of severity, so one cannot conclude the causes from the symptoms. It is relatively common for patients with non-erosive GERD to experience more symptoms than those with a complicated form. If symptoms disappear after four weeks of treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPI), this is a relatively safe indicator that no or at most minor erosions (e.g., Los Angeles A) are present, explains Marcel Halama, MD, Gastroenterology Practice, Zurich [2]. General measures for reflux symptoms are summarized in Table 1.

Reflux into the pharynx or reflux-induced vago-vagal reflex mechanisms may result in extraesophageal manifestations (e.g., cough, asthma, laryngeal symptoms, and dental erosions). Extraesophageal reflux manifestations may result from the following mechanisms:

- Direct mechanism: reflux of gastric contents up the esophagus into the respiratory tract, which can lead to aspiration pneumonia

- Indirect mechanism (more common): Gastric contents enter the distal esophagus, where distension occurs and cough or asthmatic symptoms are induced via vagal vocalizations.

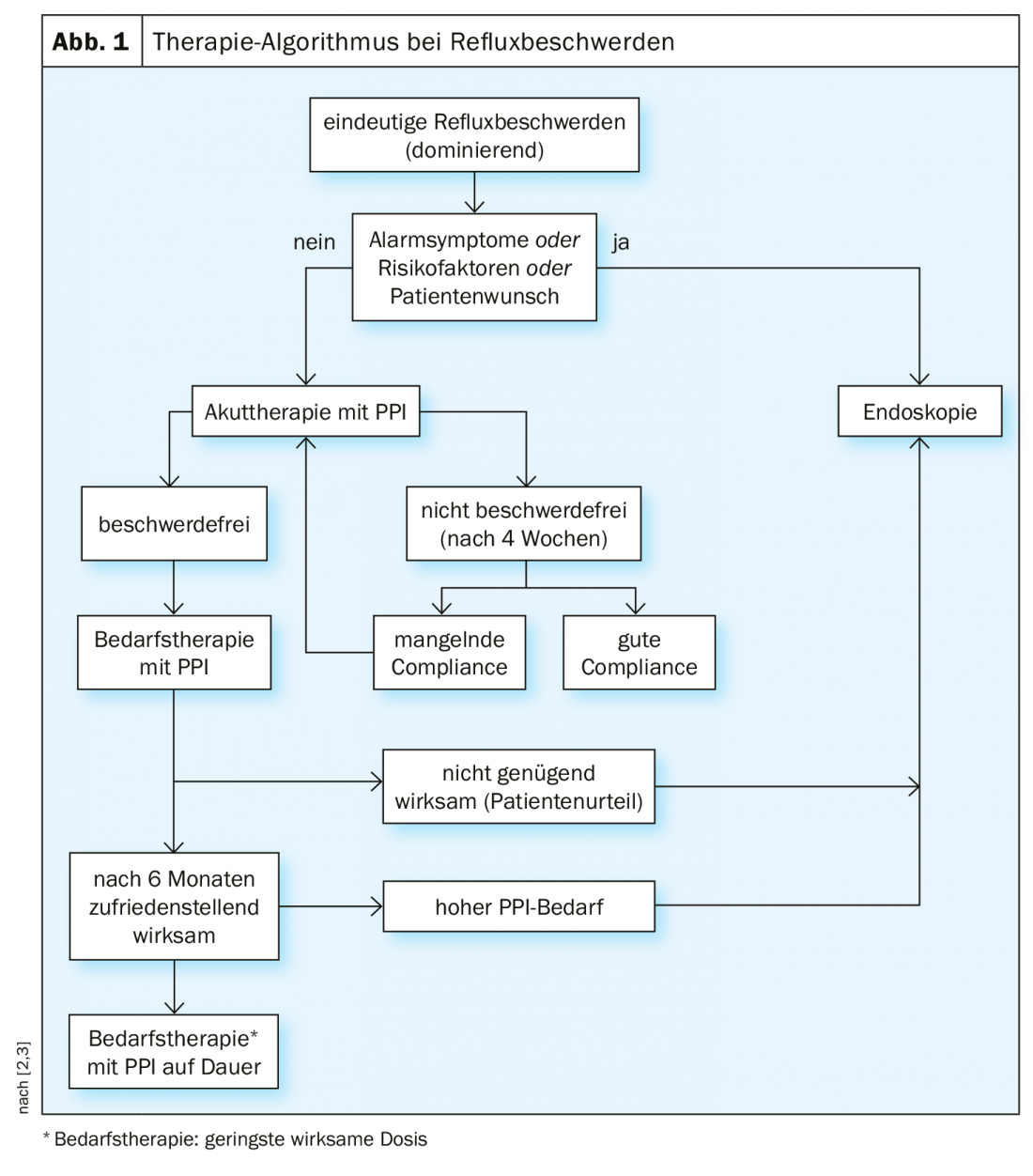

In the guidelines of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases ( DGVS), an algorithm has been formulated for the treatment of reflux symptoms (Fig. 1) [2,3]. With regard to acute therapy with PPIs, there are various representatives of this substance class that have similar efficacy both in terms of symptom control and the healing of inflammatory lesions. After a PPI treatment period of four weeks, an evaluation of the condition is recommended. If the patient is not symptom-free, it should be checked whether a lack of compliance with regard to medication intake is a possible explanation. If this is not the case, the dosage of PPI could be doubled and an endoscopy could be performed to determine whether or not it could be higher grade reflux disease. “It is now clear that Barrett’s esophagus is a manifestation of reflux disease,” said the speaker [2]. Risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus to develop into Barrett’s carcinoma: Barrett’s length >3 cm, fair-skinned, >60 years, smoker. Patients with reflux symptoms who fit this profile should be sent for surveillance endoscopy every three years.

Patients who continue to have symptoms despite 8 weeks of PPI 1×/day are said to have persistent reflux esophagitis. First of all, it should be examined whether there is room for improvement with regard to compliance. After that, medication can be tried according to the following scheme [2]:

- Double dose PPI (1-0-1) for 8 weeks.

- Antihistamine (e.g., Zantic 300 mg)

- Reflux blocker (e.g. Gaviscon 1-2 tbl. postprandially)

- Prokinetic (e.g. Motilium 10 mg)

When should surgery be performed?

If there is no relief of the reflux symptoms, it is a therapy-resistant esophagitis and it should be examined whether there is an indication for surgical intervention. In addition to PPI-refractory erosive reflux esophagitis, indications for surgery include volume reflux (usually in large hiatal hernias, i.e., >4 cm) and PPI intolerance in erosive reflux esophagitis [2]. The 5-year data for fundoplicatio are good, the speaker said. The Lotus Trial [4,5] demonstrated that both PPI and fundoplicatio were able to reduce the risk of esophageal cancer. After five years, >80% of patients in both conditions were in remission: esomeprazole (PPI)=92%, LARS (Laparoscopic Antireflux Surgery)=85%. The speaker pointed out that fundoplicatio is not suitable for all patients, however, because vomiting, for example, is hardly possible after this procedure, which can lead to unpleasant discomfort in the case of gastroenteritis. The speaker advises against fundoplicatio, especially in younger individuals and athletes. There are the following relatively new alternatives of surgical treatment:

- Magnetic band: a chain consisting of magnets is implanted around the lower opening of the esophagus. The attraction of the magnets narrows the esophageal entrance for rising stomach acid, but is weak enough for incoming food to pass.

- Endostim: Laparoscopically, two electrodes are inserted into the gastroesophageal junction and connected to a subcutaneously implanted pacemaker. The pacemaker can be adjusted electromagnetically via a tablet. The nerve leading to the sphincter is stimulated via the pacemaker

Side effects of long-term PPI therapy

In recent years, there has been increased research on a possible association of long-term PPI use with the increased occurrence of various adverse effects [2]. Acid-independent side effects include: Microscopic collagen colitis, acute interstitial nephritis, chronic kidney disease. Possible acid-dependent side effects include: bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine, gastrointestinal infections, hypomagnesemia, gastric carcinoma, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy.

The evidence on whether long-term PPI use increases the risk of osteoporosis is controversial. No clear recommendations are possible, the speaker said. He manages it so that in risk groups with longer-term PPI therapy (e.g., young women), calcium is prescribed as an add-on. There is also no consensus on the question of whether long-term PPI use increases dementia risk. According to a prospective Danish study published in 2018, there is no statistically demonstrable association [6].

Source: FOMF Zurich

Literature:

- Sauter M, Fox MR: The acid pocket: a new target for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Z Gastroenterol 2018; 56(10): 1276-1282.

- Halama M: Slide presentation Marcel Halama, MD, Gastroenterology Practice, Zurich. Ulcer and reflux disease. FOMF Internal Medicine – Update Refresher, 04.12.2019, Zurich.

- German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases, www.dgvs.de

- Galmiche JP, et al: Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2011; 305(19): 1969-1977.

- Maret-Ouda J, et al: Risk of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma After Antireflux Surgery in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in the Nordic Countries. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4(11): 1576-1582.

- Wod M, et al: Lack of Association Between Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Cognitive Decline. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2018; 16: 681-689.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(1): 32-33 (published 1/25/20, ahead of print).